5 Volumes

Constitutional Era

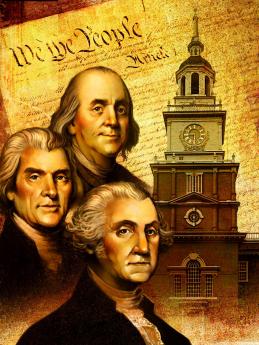

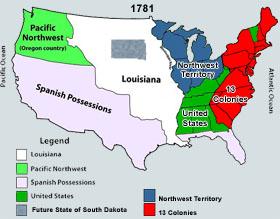

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

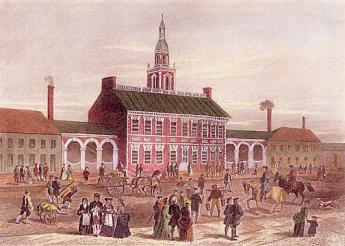

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Four Constitutions

Multi-national unions of republics are uncommon, usually brief and seldom voluntary. America has had three of them, but we only got it right the second time. Uncertain why we succeeded when many others failed, we remain skeptical of changing the rules. The Europeans, on the other hand, are uncertain whether they want to follow the Confederate States of America toward extinction, or the United States of America toward world domination. When deeply considered, it is a hard choice.

Constitutionalism: American Mixtures of A Republic and a Democracy

New volume 2017-03-12 19:22:27 description

..The Constitution

Our Constitution was not a proclamation written by a convention. It was a negotiated contract for uniting thirteen sovereign independent states. Nothing like that had ever been done voluntarily, and few nations have matched it in two hundred years, even with the use of force.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

|

| Preamble, by Gouverneur Morris |

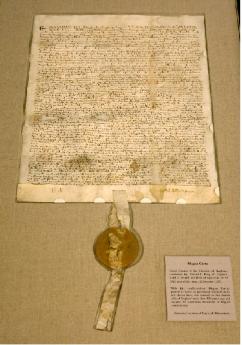

NATIONAL constitutions are an outgrowth of the 18th Century Enlightenment, even though some similar features are found in ancient legal codes. Those who trace the American constitution to the 13th Century Magna Carta usually attach it to a central sentence of its clause 39:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

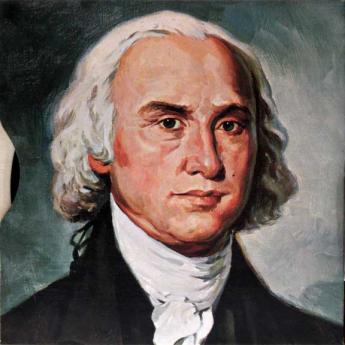

The Magna Carta proclaims that government may not use force against a citizen unless the nation had collectively embraced the principle which was being invoked. That's surely a sound legal doctrine, but it's unrecognizeable as a Constitution. For that, it lacks structure and specifics for actually going ahead with it. Viewed in that light, the Magna Carta resembles the Iliad and Odyssey, which illustrate many of the behaviors which the Greeks thought were worthy, but does not connect them to an organized structure of governance. Many philosophers of government during the Enlightenment period also neglected to confront where their ideas might be taking them. Indeed, the American Constitution was even the first Constitution to be written out, which struck others as a novel idea. Seldom among the writings of Montesquieu (The Spirit of the Laws, 1748), Catherine the Great (Nakaz, Instructions to the All-Russian Legislative Commission, 1767), Diderot (Observations About Nakaz, 1774), can there be found a contract for government design or its main contingencies. Certainly there is no such specificity within the writings of Adam Smith, if we look for rule-making among Enlightenment thinkers whose ideas strongly influenced the 1787 Philadelphia document. The American Constitution was the product of many minds, before and after 1787, chiefly James Madison's. Its nearly final form emerged from the Constitutional Convention of the summer of 1787, held in Philadelphia with Gouverneur Morris as penman, or editor. To him we owe its pleasing succinctness, which is a main source of national affection for the document. That may have been artful; in his diary of the secret meetings, James Madison records that Gouverneur Morris rose to speak about 170 times, more than any other delegate. Lots of thought and debate; ultimately, few words.

The Elizabethan Sir Francis Bacon is thought to have the greatest claim on devising a theory of communal law-making in the Anglican tradition, now called the Common Law. His elegant modification of Galileo's 16th Century creation of the scientific method originated mostly as a proposed methodology for devising good laws, which over time the entire legal profession then evolved into England's preferred legal principles. However, tracing the American Constitution back to an underlying British one stumbles when the evolved British Constitution fails to meet a definition which would include America's constitution, which has become the premier model. The British Constitution is said to be "unwritten" to the degree it is a consensus of revered documents, defining its culture, not its government. It can be amended by Parliament at will, has a turbulent history of specifying just who is covered by it, and in order to define constitutional principles seems to rely on sentences extracted from difficult context. If the two constitutions had been written and compared at the same time, one would say the British had sacrificed cohesiveness out of respect for tradition. In fairness, some features of the American constitution are also unnecessary for every constitution, but by surviving as part of the oldest constitution in the modern form, have now become part of the model. The essence would be:

A set of principles establishing the legitimacy of a nation's laws, remaining firmly above them within the modified Republic it describes. It defines its domain by defining the voting requirements of its citizenry, loosely deriving geographical sovereignty by treaty with its neighbors. It supersedes all other governance within its domain. It respects its own origins but when it conflicts, locates sovereignty in the will of its citizens. It includes a description of how to amend it, which is intentionally difficult. It goes on to outline the overall structure of the laws it regulates, with subtle modifications to channel the type of structure which will result. The rights of life, liberty and property were axiomatic, with property left unspoken within the pursuit of happiness.

|

| Independence Hall |

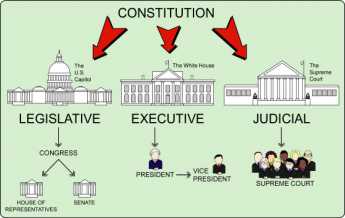

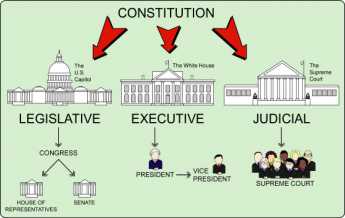

In the American view, history contained a few extra temptations of all governments, so troublesome their restraint justified the extra difficulty of amendment at the Constitutional level. To lessen controversy, these Rights might be regarded as coming from God, but they are vaguely described here as innate in the human condition. The overall government design was to be: a bicameral republican legislature, with separated executive and judicial branches. But that was only a federal superstructure, confined to a few enumerated national powers essential to maintaining Union; state governments retain all other unenumerated powers, and when unaddressed by the states were retained by the people. Incomplete but prominent operational features would be:

Separation and re-balancing government powers among the national government branches and/or federated states, reducing the power of governmental departments to dominate each other, and thus enhancing citizen liberty from all parts of dominating government by enhancing citizen power to shift allegiance between federal branches, and between states and federal. Powers were not only separated, but when possible given the means to maintain and defend their independence from each other. Even domination by large or populous states was restrained. Church and State were proclaimed forever separate, for like purpose. A right was given to citizens to bear arms, perhaps strengthening citizens' defense against external attack but primarily to reduce government's monopoly of military power in the event of citizen rebellion against government dominion. And perhaps to warn that revolt was possible, even endorsed, as some final extremity in defense of liberty. Widespread wariness about government abuses of power stems from the fact that most American citizens in 1787, had until recently been revolutionaries themselves and sympathized with that stance.

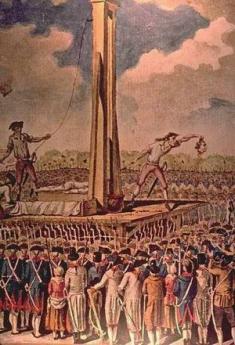

It probably enhances our understanding to mention the contrasting outcome of competitive 18th Century implementations of the Constitution idea. Russia's Catherine the Great proposed a constitution steeped in the traditions of the Enlightenment, but ultimately designed to define and strengthen the role of the monarch. Denis Diderot her French protege recoiled, substituting other views of citizen power resembling those of Jean Jacob Rousseau. Diderot opened Observations About Nakaz his commentary to the Queen, with the following declaration:

There is no true sovereign except the nation; there can be no true legislator except the people.

With this ringing warcry, the extremist French model ushered in the opposite outrages of the Terror, the Guillotine, and the Napoleonic conquests. The French constitution and its consequences undermined world confidence in the universal benevolence of public opinion, deeply confounding those for whom democratic rule was paramount. Observing this, a certain amount of new life was breathed into allegiance for monarchy, military rule, and dictatorship. If mankind were innately good, how could national opinion so promptly overturn other standards of decency? Public opinion was apparently neither invariably benign, nor necessarily far-seeing. The "noble savage", human nature naked of the taint of civilization, was not invariably wise or worthy of trust. Edward Gibbon, the 1776 author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was perhaps pointing out, to believers in the collective goodness of the human condition, where mistakes might lead. At the least, the failure of the French Revolution strengthened the reputation of Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, who in 1776 had urged national reliance on a sense of collective self-interest, as follows:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we can expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

Diderot rejected Catherine's view of things, although in view of his dependence on her, it is unsurprising he would withold publishing his rejection of it until 1823. Thomas Jefferson was in France as ambassador at the time of the Constitutional Convention, and fearing to confront George Washington, also kept his conflicting views private for several years. Eventually they surfaced in the creation of an anti-Federalist political party and in the roiling conflicts of the next forty years, which offer abundant reasons for American and Madisonian humility about anyone's constitutional skills. It is however a testimony to the strength of the Constitutional Convention's design that the country was then able to waver between two extreme governing philosophies without requiring a change in the Constitution. Indeed, it is plausible to contend that our political parties continue to waver quite usefully between these two vituperative opinions, in spite of the shudders of the rest of the world. The core of the Constitution is succinctly described: It's an Enlightenment variant of the Roman Republic. In addition, it contains two satellite concepts: the English Common Law as modified by John Marshall and the rest of the American legal profession, and the financial structure devised by Robert Morris and Alexander Hamilton, which has evolved into an acrimonious feature which no one pretends to understand fully, but which succeeds better than any competitor. These two occasionally erupting volcanoes, the legal and the financial, are here treated separately from the legislative Republic to serve reader comprehension. Always remembering, however, that no one entirely understands why the arrangement has worked so well. Describing the growth of presidential power is less descriptive, more apprehensive, and treated separately as well.

Washington Picks out Madison

Washington had been an outstanding athlete, soldier, and farmer. Travel in the Eighteenth century was hard, but he enjoyed exercise. Disconcertingly, travel after the war reinforced his wartime conviction that something vital was missing. State disunity was if anything worse after the Revolution. More formal organization was needed than just a confederation so big others would leave it alone. By 1787, Washington concluded the state legislatures would not surrender power unless more people insisted on it. Even dire military consequences had not always transformed flight into resolution. In peacetime, the new leadership class would likely scatter because peace attracts mediocrity to office, and mediocrity fights hard to keep its place. That left it up to prominent men in the community, gathered in a Constitutional Convention to suggest a list of advantages of Union, and peaceful ways to maintain it. That's not exactly what is now meant by "We, the People", demanding liberty, but it served at the time.

The French Revolution was soon to demonstrate how unwise it was to look for short-cuts; we needed a republic, not anarchy. Washington was unsure just what else was needed, but he knew a few basic things with certainty. For one thing, we needed a bargain that everyone involved was expected to keep. The amendment would be provided for, but it would be difficult.

Two small sections, Eight and Nine of Article One, list the separations of state and national sovereignties in very sparing language. The states must avoid using their sovereignty to gain the advantage over each other. Defense of the coasts against piracy and a general postal system is a Federal responsibility. As are open borders between the states, both physical and economic, promoting trade to the advantage of everyone. Uniformity of weights and measures, patents and copyrights, currency and coinage, bankruptcy and naturalization rules permit everyone to aspire to wider and easier markets. Uniform rights unite the various subcultures, so a general prohibition was declared of ex post facto laws and suspension of habeas corpus, degrading the currency, injuring the sanctity of contracts (or by implication injuring all the centuries of legal consensus known as the common law). Everyone knew state legislatures had either ignored or flouted these principles; state interference in these particulars was therefore expressly prohibited. Desirable federal powers were stated in a positive way, and limited to what was stated. However, because there remained doubters even after the Constitution was put into action, the Tenth Amendment was soon added to restate the point:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

There were plenty of other negative ways to put all this, but the Constitution said no more than necessary. Certain powers were essential for a functioning national government, while some few powers would be destructive if the component states exercised them. The framers might have said but did not say: Look at what has happened among the little countries of Europe; the same thing might also happen to us. As Adam Smith had recently warned, avoid economic discriminations against foreigners which are lumped under the heading of Mercantilism; in other words, avoid the use of government power to favor local businesses against competitors outside the political boundaries who therefore have no local influence. Let several states avoid the expense and nuisance of different coinages, tariffs, licenses, and cartels. The inability to assemble parts of manufactures in different jurisdictions, using different rules and regulations, seemed mainly designed to increase prices for the general mass of consumers for the benefit of a few politically well-placed producers, who should enjoy such advantages only if they earn them. In some ways, these negative arguments had the greatest persuasive force, because almost everyone could think of some injury inflicted by similar laws. In 1787 it was only recently that our whole nation had suffered from the mercantile rules of Great Britain, who was supposedly a partner with the colonies. Exhortations with this sort of specificity were excluded from the document. Private publications like the Federalist Papers could be more explicit because they were not official parts of the agreement, and thus could be more easily reshaped by the courts. Those who today confine Original Intent to specifics are treading on soft ground.

|

| The Constitutional Convention |

It was hard to know where to stop with these arguments. A promise was being made that the nation would prosper with expansions of scale, and in fact, it soon did. It was also foreseen that expansion of the right of the federal government to tax would automatically constrict the ability of the states to do so, and in time the state legislatures have been reduced to begging for federal funds. [At the same time, it seems inconceivable that the Constitutional Convention would have condoned the present discordance between the several states in what federal taxes they pay compared with what federal benefits they receive.] The states' inability to levy troops and declare wars has indeed reduced local power to intervene to block hostilities, not of local concern. There have been occasions to fear that plebiscites for personal freedom may have sometimes impaired the nation's ability to defend itself. Local gasoline and cigarette tax wars occasionally spring up to exploit differences in state taxation, but in general, there remains comparatively little mercantilism at a state level. But regional differences have correspondingly grown, along with the sense of local powerlessness to resist it. The Civil War is only the largest example of a general trend of shifting conflicts into those gaps of jurisdiction unimagined by the framers. Section Eight arguments all rode on the rising tide of the Industrial Revolution; they proved in general to depict correct predictions. But they also persuaded 600,000 young men to die, for or against the Union itself.

Designing the Convention

|

| The Convention and the Continent |

THE prevailing notion of the Constitutional Convention once depicted James Madison as seized with the idea of a merger of former colonies into a nation, subsequently selling that concept to George Washington. The General, by this account, was known to be humiliated by the way the Continental Congress mistreated his troops with worthless pay. But recent scholarship emphasizes that Washington noticed Madison in Congress becoming impassioned for raising taxes to pay the troops, was pleased, and reached out to the younger man as his agent. Madison seemed a skillful legislator; many other patriots had been disappointed with the government they had sacrificed to create, but Madison actually led protests within Congress itself. A full generation younger than the General and not at all charismatic, Madison's political effectiveness particularly attracted Washington's attention to him as a skillful manager of committees and legislatures. Washington was upset by Shay's Rebellion in western Massachusetts, which threatened to topple the Massachusetts government, but Shay's frontier disorder was only one example of general restlessness. There was a long background of repeated Indian rebellions in the southern region between Tennessee and Florida, coupled with uneasiness about what France and England were still planning to do to each other in North America. It looked to Washington as though the Articles of Confederation had left the new nation unable to maintain order along thousands of miles of the western frontier. The British clearly seemed reluctant to give up their frontier forts as agreed by the Treaty of Paris, and very likely they were arming and agitating their former Indian allies. Innately rebellious Scotch-Irish, the dominant new settlers of the frontier, were threatening to set up their own government if the American one was too feeble to defend them from the Indians. The Indians for their part were coming to recognize that the former colonies were too weak to keep their promises. With the American Army scattered and nursing its grievances, the sacrifices of eight years of war looked to be in peril.

The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured ... by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was "to form a more perfect Union.

|

| A.Lincoln, First Inaugural |

Even Washington's loyal friends were getting out of hand; Alexander Hamilton and Robert Morris had cooked up the Newburgh cabal, hoping to provoke a military coup -- and a monarchy. Because they surely wanted Washington to be the new King, he could not exactly hate them for it. But it was not at all what he had in mind, and they were too prominent to be ignored. So he had to turn away from his closest advisers toward someone of ability but less stature and thus more likely to be obedient. It alarmed Washington that republican government might be discredited, leaving only a choice between a King and anarchy. Particularly when he reviewed shabby behavior becoming characteristic of state legislatures, something had to be done about a system which proclaimed states to be the ultimate source of sovereignty. Washington decided to get matters started, using Madison as his agent. If things went badly he could save his own prestige for other proposals, and Madison could scarcely defy him as Hamilton surely would. Washington could not afford to lose the support of the two Morrises, and still, expect to accomplish anything major. Madison had been to college and could fill in some of the details; Washington merely knew he wanted a stable government and he did not, he definitely did not, want a king. Many have since asked why he renounced being King so violently; it seems likely he was projecting a public rejection of the Hamilton/Morris concept in a way that did not attack them for proposing it. It was a somewhat awkward maneuver, and to some degree, it backfired and trapped him. But Madison proved a good choice for the role, and things worked out reasonably well for the first few years.

The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the Federal Government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State Governments are numerous and indefinite.

|

| J.Madison, Federalist#45 |

Madison was young, vigorous and effective; he held the widespread perception of the Articles of Confederation as the source of the difficulty, and he was a reasonably close neighbor. He was active in Virginia politics at a time when Virginia held defensible claims to what would eventually become nine states. Negotiations for the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 would be going on while the Constitutional Convention was in session, and Virginia was central to both discussions. After conversations at Mount Vernon, a plan was devised and put into action. Washington wanted a central government, strong enough to energize the new nation, but stopping short of a monarchy or military dictatorship. There were other things to expect from a good central government, but it was not initially useful to provoke quarrels. Madison had read many books, knew about details. Between them, these two friendly schemers narrowly convinced the country to go along. As things turned out, issues set aside for later eventually destroyed the friendship between Washington and Madison. Worse still, after seventy years the poorly resolved conflict between national unity and local independence provoked a civil war. Even for a century after that, periodic re-argument of which powers needed to revert to the states, which ones needed to migrate further toward central control, continued to roil a deliberately divided governance.

|

| Constitutional Convention |

For immediate purposes, the central problem for the Virginia collaborators was to persuade thirteen state legislatures to give up power for the common good. The Articles of Confederation required unanimous consent of the states for amendment. To pay lip-service to this obstacle, it would be useful to convene a small Constitutional Convention of newly-selected but eminent delegates, rather than face dozens of amendments tip-toeing through the Articles of Confederation, avoiding innumerable traps set by the more numerous Legislatures. In writing the Articles of Confederation, John Dickinson had been a loyal, skillful lawyer acting for his clients. They said Make it Perpetual, and he nearly succeeded. The chosen approach to modification was first to empower eminent leaders without political ambitions and thus, more willing to consent to the loss of power at a local level. Eventual ratification of the final result by the legislatures was definitely unavoidable, but to seek that consent at the end of a process was far preferable because the conciliations could be offered alongside the bitter pills. Divided and quarrelsome states would be at a disadvantage in resisting a finished document which had already anticipated and defused legitimate objections and was the handiwork of a blue-ribbon convention of prominent citizens and heroes. By this strategy, Washington and Madison took advantage of the sad fact that legislatures revert toward mediocrity, as eminent citizens experience its monotonous routine and decline to participate further in it, but will make the required effort for briefly glamorous adventures. Eminently successful citizens are somewhat over-qualified for the job, whose difficulties lesser time-servers are therefore motivated to exaggerate. To use modern parlance, framing the debate sometimes requires changing the debaters. In fact, although he had mainly initiated the movement, Washington refused to participate or endorse it publicly until he was confident the convention would be composed of the most prominent men of the nation. This venture had to be successful, or else he would save his prestige for something with more promise. Making it all work was a task for Madison and Hamilton, who would be replaced if it failed.

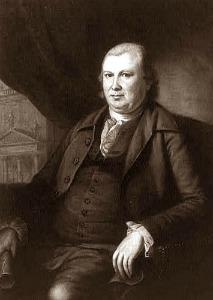

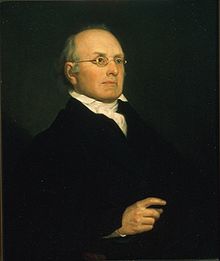

|

| John Dickinson |

While details were better left hazy, the broad outline of a new proposal had to appeal to almost everyone. Since the new Constitution was intended to shift power from the states to the national government, it was vital for voting power in the national legislature to reflect districts of equal population size, selected directly by popular elections. That was what the Articles of Confederation prescribed. But no appointments by state legislatures, please. In the convention, it became evident that small states would fear being controlled by large ones through almost any arrangement at all. On the other hand, small states were particularly anxious to be defended by a strong national army and navy, which requires a large population size. England, France, and Spain were stated to be the main fear, but small states feared big neighboring states, too. Since the Constitutional convention voted as states, small states were already in the strongest voting position they could ever expect, particularly since the Federalists at the convention needed their votes. Eventually, the agreement was found for the bicameral compromise suggested by John Dickinson of Delaware, which consisted of a Senate selected and presumably voting as states, and a House of Representatives elected in proportion to population; with all bills requiring the concurrence of both houses. From the perspective of two centuries later, we can see that allowing state legislatures to redraw congressional districts gives them the power to "Gerrymander" their election outcomes and hence restores to the populous states some of the internal Congressional power Washington and Madison were trying to take away from them. In the 21st Century, New Jersey is an example among a number of states where it can fairly be said that the decennial redistricting of congressional borders accurately predicts the congressional elections for the following ten years. The congressional seniority system then solidifies the power of local political machines over the core of Congressional politics. However, the irony emerges that Gerrymandering is impossible in the Senate, and hence legislature control over their U.S. Senators has been weak ever since the 17th Amendment established senatorial election by popular vote. That's eventually the opposite of the result originally conceded by the Constitutional Convention, but possibly in accord with the wishes of the Federalists who dominated it.

|

| Electoral College Method for Election of the President |

This evolving arrangement of the national legislative bodies seemed in 1787 an improvement over the system for state legislatures because the Federalists believed larger legislatures would contain less corruption because they had more competing for special interests to complain about it. There were skeptics then as now, who wished to weaken the tyranny of the majority so evident in the large states and in the British parliament. To satisfy them, power was redistributed to the executive and judicial branches, which were intentionally selected differently. Here arises the source of the Electoral College for the election of the President. It gives greater weight to small states (and provokes a ruckus among large states whenever the national popular vote is close). Further balance in the bargaining was sought by lifetime appointments to the Judiciary, following selection by the President with the concurrence of the Senate. Without any anticipation in this early bargaining, an unexpectedly large executive bureaucracy promptly flourished under the control of the chief executive, lacking the republicanism so fervently sought by the founders everywhere else. This may be in harmony with the Federalist goal of removing patronage from legislature control, but Appropriations Committee chairmen have since found unofficial ways to assert pressure on the bureaucracy. It's quite an unbalanced expedient. Only in the case of the Defense Department is the balancing will of the Constitutional Convention made clear: the President is commander in chief, only Congress can declare war. Although this difficult process was meant to discourage wars, it mainly discouraged the declaration of wars; other evasions emerged. From placing the command under an elected President, emerges a stronger implicit emphasis on civilian control of the military, loosely linked to the fairly meaningless legislative approval of initiating warfare. There have been more armed conflicts than "declarations" of war, but no one can say how many there might otherwise have been. And there have been no examples of a Congress rejecting a President's urging for war.

And that's about it for what we might call the first phase of the Constitution or the Articles. In 1787 there arose a prevalent feeling that national laws should pre-empt state laws. In view of the need to get state legislatures to ratify the document however, this was withdrawn. The Constitution was designed to take as much power away from the states as could be taken without provoking them into refusing to ratify it. Since ratification did barely squeak through after huge exertions by the Federalists, the Constitution closely approaches the tolerable limit, and cannot be criticized for going any further. Since no other voluntary federation has gone even this far in the subsequent two hundred years, the margin between what is workable and what is achievable must be very narrow. Notice, however, the considerable difference between Congress having the power to overrule any state law, and declaring that any state law which conflicts with Federal law is invalid.

The details of this government structure were spelled out in detail in Sections I through IV. However, just to be sure, Section VI sums it all up in trenchant prose:

This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding. The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.

Except for some housekeeping details, the structural Constitution ends here and can still be admired as sparse and concise. That final phrase about religious tests for office sounds like a strange afterthought, but in fact, its position and lack of any possible ambiguity serve to remind the nation of grim experience that only religion has caused more problems than factionalism. Madison was particularly strong on this point, having in mind the undue influence the Anglican Church exerted as the established religion of Virginia. There are no qualifications; religion is not to have any part of government power or policy. By tradition, symbolism has not been prohibited. But government as an extension of religion is emphatically excluded, as is religion as an agency of government. Many failures of governments, past and present, can be traced to an irresolution to summon up this degree of emphasis about a principle too absolute to tolerate wordiness.

IF ALL MEN WERE ANGELS, NO CONSTITUTION WOULD BE NECESSARY

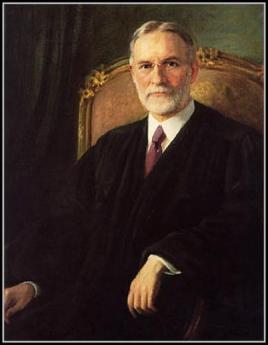

|

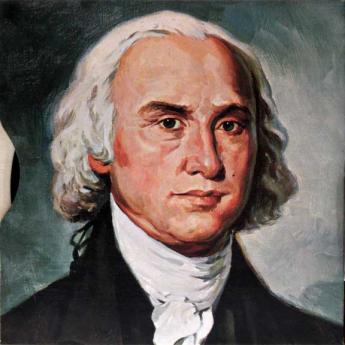

| James Madison |

JAMES Madison, Washington's floor manager at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia, stated the main necessity for holding the Convention at all arose from selfish and untrustworthy human nature. The assembly probably understood exactly who he had in mind, although that is a little unfair to residents of Virginia. He really meant everybody. In the theology of the time, mankind was stained with original sin. Particularly in France, many 18th century romanticists responded to the Enlightenment by defiantly declaring human nature is born pure in heart. In their view, current evils grow from the pollution of civilization, without which it might be possible to have no government at all. At its root, such romanticism was an outcry against progress and civilization, blaming the world's troubles on the Industrial Revolution, so to speak. From Madison's skeptical viewpoint, the most awkward feature of the Romantic Period was its adoption by his Francophile friend and neighbor, Thomas Jefferson, the current American ambassador to France. Madison recognized that Jefferson and Patrick Henry were prepared to assail any attempt to add the slightest power to a central government, particularly if it weakened the power of Virginia. As indeed they promptly came forward to do and nearly succeeded.

|

| Treaty of Paris |

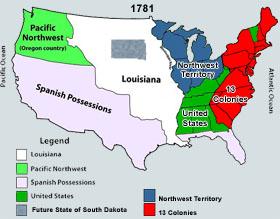

After fighting an eight-year war for freedom, American belief was wide-spread that it was time to draw back from such anarchy. But there was widespread suspicion in every other direction, too. England seemed to concede, not defeat but only current military overstretch, possibly displaying reluctance to see its former colonies with full sovereignty. George III might wait for America to weaken itself and then try to take them back. Britain almost couldn't do anything right; it was also possibly up to no good when the Treaty of Paris astonishingly conceded land to the Mississippi instead of stopping at the Appalachians. Even our ally France nursed regrets for its somewhat older concessions after the French and Indian War. If even the two mightiest nations of Europe could not maintain order in the vast North American wilderness, perhaps they felt the inexperienced colonies would soon collapse from the effort. Further intra-European wars seemed likely, and could soon spread from Europe to the Western hemisphere. The guillotine was bad enough, Bonaparte would be worse. Our governance as a league of states was in fact, only a league of armies. The Articles of Confederation would not quell inter-state rivalries in peacetime, as only four years (1783-87) experience after the Treaty of Paris were clearly foreshadowing. It was time we listened to Benjamin Franklin, who had been arguing since the Albany Conference of 1745 for unification of the colonies, and to Robert Morris who had been arguing for a written constitution since 1776, a bicameral legislature since 1781, government by professional departments instead of congressional committees, and the ability to levy national taxes -- since at least 1778. Professor Witherspoon of Princeton had provided some ideas about how to make these proposals self-enforcing, Washington was firmly behind a Republican system and opposed to a monarchy. On the other hand, everyone knew that under the Articles of Confederation the thirteen States had often refused to pay their share, abused their ability to deal independently with foreigners, dealt unfairly with their neighbors, and capriciously mistreated their own citizens. It was time to act boldly. With a blue-ribbon convention of national heroes behind these simple ideas, surely it would be possible to convince the sovereign state legislatures to dethrone themselves.

|

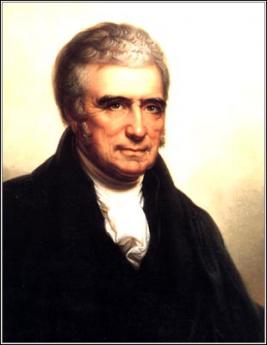

| John Marshall |

Two men quietly applied even deeper thinking than that; Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, and John Marshall of Virginia. Both of them had served in state legislatures, both were dismayed by the experience. Franklin also had a long period of close-up observation of the British Parliament, suffering personal abuse there, and had reason to reflect on the earlier abuses by that Parliament under Cromwell during the English Civil War. Certain bad tendencies seemed universal in legislative bodies. Although John Marshall was not a member of the Virginia Constitutional delegation in 1787, he was active in the politics of the group it represented back home. Both Marshall and Franklin had reason to be uneasy about misbehavior in representative bodies, whether called legislatures, congresses, or parliaments. When people said states misbehaved under the Confederation arrangement, they really meant legislatures misbehaved. Franklin did what he could within the Convention to curb this observed behavior by enumerating limited powers and endorsing power balanced against power. When he had nudged it as far as he could, he wearily agreed to give the product a try. Franklin did not trust Utopias, but he had lived among Quakers for years, observing one Utopian society which seemed to endure without resorting to tyranny.

The Constitutional provisions in Article I, Section X became the heart of what the 1787 Convention wanted to change about the relationship of the national and state governments.

States are forbidden to ...

"emit bills of credit, make anything but gold or silver a legal tender in payment of debts, pass any bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law impairing the obligation of contracts."

|

| 1787 Convention |

This brief clause is almost a presentment of what state legislatures were doing, which serious patriots regarded as wholly unacceptable. Failure of states to abide by the terms of international treaties must be included in such a summary, although the new Constitution went beyond the powers of states by locating treaties beyond the power of even Congress to change, once ratified. Some observers in fact feel that within the First Article clause, protecting the sanctity of contracts was really the nut of the matter. In one way or another, most states seemed to resort to paying their debts with inflation, somehow failing to recognize that borrowing never pays debts, it only postpones them. The great bulk of this new nation's business was to be conducted as voluntary agreements between two contracting parties. The State -- and the states -- were to stay out of the private sector, except as referee, to see that both sides kept their agreements. As a footnote, the matter of government intervention in private affairs was to rise again in the behavior of the Executive branch in the 1937 Court Packing uproar, and in the 2009 health insurance legislation. Some critics, therefore, have discomfort that the heaviest Constitutional weight was placed by the Founding Fathers on protecting private property. Are not other issues more important, they ask, like life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? The Founders, of course, we're here not ranking benevolences by value; they were stating principal urgencies for convening the meeting. In a strange unintended way, they here stumbled on the right to property as the foundation for all other rights. But John Marshall understood it was true and was to spend thirty years hammering it into place. People broke individual promises by defaulting on debts; they simply did the same as governments, using inflation.

Go to Delaware, Elephants?

|

| Dead Elephant |

No one is supposed to know where elephants go to die, but if they are smart as people say they are, my suggestion is to search for dead elephants in the state of Delaware. Most taxes, and estate taxes, in particular, are considerably lower, there. At least this was the message Christopher J. Topolewski, Esq. conveyed to the Right Angle Club recently. His firm, West Capital Management, has prepared a table comparing the taxes in the three states that come together at the southeast corner of Pennsylvania, which for residents of the Philadelphia area are within easy commuting distance of each other. Although Delaware has a marriage penalty (one couple is taxed more than the sum of two singles), it has no estate tax at all, no sales tax, and a property tax rate only half that of Pennsylvania, only a quarter of that in New Jersey. For residents of New Jersey, there is almost no tax which is not lower in Delaware, because but ex-Pennsylvanians would then have to be careful to die or cohabit since ordinary income tax and capital gains taxes are higher in Delaware than Pennsylvania. If you must die (and who doesn't?), go die in Delaware.

This was a situation specifically contemplated as a way to discipline greedy state governments, by James Madison when he was formulating the U. S. Constitution. And there is evidence it is working. By happenstance, I once encountered an official of New Jersey taxation, who told me that 43% of New Jersey taxes are paid by 1% of the population. And that 1% was moving out of the state as fast as it could. If it does, the other 99% of New Jersey residents will find their taxes rising by 43%. West Capital reports that taxation as a percent of income is 1.23% in Delaware, 3.46% in Pennsylvania, and 5.82% in New Jersey, suggesting that a selective flight of the 1% would raise the state taxes of everyone else by 43%, and thus make state taxation as a percent of lowered average income rise to roughly 20%. Relating total income to total tax revenues would be an even better way to detect hidden indirect taxes, such as overtaxing utilities in the knowledge it will be passed on to the consumer. I recently discovered that a few years ago, the Legislature got tired of hearing complaints about local taxes, so they transferred half of the local taxes to the state tax. That's pretty much like taking it from one pocket and putting it into another because now all the hubbub is about state taxes. Armed with even partial information, it becomes easier to understand why New Jersey would evict a governor who had been Co-chairman of Goldman Sachs, during a financial crisis. If a financial whiz can't change this, maybe it requires a meat ax.

This is a time of growing restlessness about public spending, and Tea Party revolts are likely to accelerate during the remaining nine months before the next election. The conjecture is growing about a coming deadlock between a Republican Congress and a Democratic President, lasting at least two more years. What might emerge from a strong third party congressional delegation is too arcane to discuss. But at least the Republicans who leave can console themselves they are selectively raising the taxes of Democrats.

It seems almost inconceivable that professional politicians would demonstrate such a forest of tin ears as to let this happen, but the rest of Mr. Topolewski's talk just heated up the fire. His long-scheduled talk was designed to give guidance about the new estate tax laws, but he found himself confounding his audience with the news that there are no new estate tax laws; in fact, there will be no estate tax laws at all after this year unless they emerge from the congressional gridlock we already have. Which apparently will be followed by a gridlock we can scarcely imagine. Imagine asking your lawyer to write a will which straddles the contingencies that there will be no law, that there might be a continuation of the present one, or there might be some new law of quite uncertain wording. One of the suggestions offered is to allow your executor the discretion to accept or disclaim certain hypothetical provisions.

And that brings up an old story. William Penn was the largest private landowner in the history of America, possibly the whole world. He had a trusted agent, who gave him an enormous pile of papers to sign. A busy rich man like Penn is regularly confronted with a discouragingly large number of routine legal documents to sign. So, Penn signed them all, not noticing that one of the various papers in the pile gave the entire state of Pennsylvania -- to his agent. The outcome of the ensuing uproar was that Penn spent six years in debtors prison.

Reversing Madison's Scheme

|

| Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee |

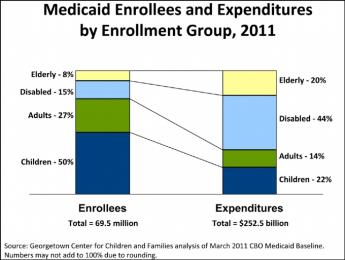

Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee was once the Governor of Tennessee. He, therefore, faced the eternal problem of finding enough revenue to cover the expenditures of the state government, which quickly runs against a barrier. Local taxes cannot be raised significantly higher than in other states -- before the wealthier inhabitants start moving to some cheaper state. In our current era of the welfare state, the federal government has the option of dumping expensive welfare programs onto state governments, as a local responsibility to pay for. The net effect of this maneuver is to attract poor people to move toward states with generous welfare programs, and rich ones to move away. That is, a disincentive has been created for making welfare programs any good. Politicians obviously do not like to discuss this matter openly, so I will take the personal responsibility for stating that this perverse disincentive is the main reason Medicaid is the absolutely worst medical program in any state, chronically underfunded everywhere. Therefore, when Obamacare dumped 15 million uninsured persons onto the Medicaid rolls, it doomed them to underfunded medical care, as they will soon discover.

.jpg)

|

| Constitution |

Since this situation was created by the Constitution, only amending the Constitution can repair it. However, the U.S. Supreme Court might discover enough elasticity in its penumbras and emanations to permit a few demonstration projects, and this discussion proceeds on that assumption. Senator Alexander proposed the federal government trade financial responsibility for Medicaid to the states, in return for accepting responsibility for K-12 education. Horse-trading of this sort might have some political utility, but for demonstration projects, it is surely better to limit the number of variables in order to reach a firm conclusion, sooner. There is always a danger of unintended consequences from shifts of this magnitude, and the public knows it. Therefore, a swap is always twice as politically dangerous as a single experiment. Some other time, or maybe in some other states, but don't mix them up.

|

| Medicare program fact |

In policy circles, there is a knee-jerk reaction that moving Medicaid to the federal government would be to create a "single-payer system", which some people favored, anyway. However, the purest form of single payer would include all medical care for everybody, into Medicare for the elderly. The hidden elixir in only moving Medicaid for the poor into the Medicare program lies in the fact that Medicaid already has a means testing; if you only want to improve the care of the poor, it is undesirable to mix them with everybody else. Presumably, by the time this becomes an issue the Democrats will be anxious to undo what they have done, while the Republicans will be inspired to let them cook in their own juice. However, there will be a brief interval in which the central controversy will seem to be one of repealing Obamacare, so an adroit leader might be able to slip a demonstration project through in the uproar.

The issue of attracting immigrants in the course of designing state welfare programs is a general one, not confined to health care. It is not even confined to the state government, as the vexing problems of a porous border illustrate on a national scale. Think tanks need to put the issue on their permanent discussion list, and foreign experiments need to be analyzed as well.

ARCHITECTURE OF GOVERNMENT: (1) ARTICLES OF STRUCTURE

Although an outstanding feature of the United States Constitution is its brevity, by contrast, the Articles of Confederation which it replaced contained scarcely anything at all. Stripped of boilerplate, the Articles amounted to an oath of perpetual allegiance between thirteen colonial tribes who banded together to fight a common enemy. The document began with a firm statement that the constituent states retained their right to write their own rules. No national rules could be made without the consent of every state. Moreover, since enforcement powers remained with the states, the states could ignore national rules at will, even if they had agreed to the rules. Once the Treaty of Paris concluded the Revolutionary War conferring an immense domain to the East of the Mississippi River, the thirteen states had to decide whether to remain united in a single nation or to parcel out the wilderness into thirteen pieces within a sort of Europe of North America. They tried to continue the Articles for four peacetime years, but their populations were too small for all the tasks. They could no more govern all that territory than they could individually defeat Great Britain in the recent war. Looking ahead for a moment, after another eighty years of immigration, the southern states would reopen that issue, but in 1787 such a demanding adventure seemed too daunting to everyone. While eight years of fighting a guerrilla war loosely bound together might have seemed the most they could do, George Washington now wanted a big nation he could be proud of, and meanwhile, Britain, France, and Spain were still making threatening gestures. It seemed plausible to consider what the new leadership forged in the Revolution could propose, maybe give it a try. George Washington certainly had the stature to step forward and say that the nation need not be bound by that silly wartime oath to make the Articles "perpetual" if the times required a different approach. And that was plainly the case. No one, not even Thomas Jefferson or Patrick Henry who privately disagreed, had the courage to confront the General.

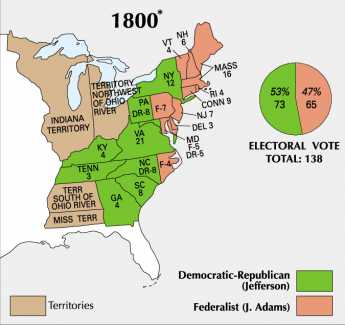

Washington was in the embarrassing position of having made a great show of permanently withdrawing from public life, but he was willing to stage-manage his way around that issue. The greater problem was his inexperience in the design of governments; he had not even gone to college and was uncomfortable about it. His young Virginia neighbor James Madison had studied the matter seriously with Witherspoon at Princeton and was anxious to make a name for himself as the designer of a new government, basking in the protection of the great General. There was general agreement that the New England town meeting version of democracy, based on small towns in ancient Athens, was unsuitable without a better way to expand its size. Well before young Madison appeared on the scene, Great Britain had popularized the Roman Republic as a model, and it became practically a foregone conclusion the United States should be a republic. Local communities should identify some trusted representative to understand and represent their interests within a deliberative body collecting the best interests of the whole nation. Unfortunately, this had been vaguely the concept of the Continental Congress, in which actual governance was conducted through select committees of the Congress. It had really not worked very well, and Robert Morris as acting administrator in 1778 immediately replaced administrative committees with permanent departments of administration, which worked much better. The leaders of Revolutionary America were in rebellion against a heavy-handed King, so they intentionally avoided a chief of state who might get ideas resembling those of Julius Caesar. However, the contrasting experiences of Congressional committees and Morris's permanent departments emerged as fairly decisive after anti-monarchy feelings began to subside. Washington remained adamant he wanted no part of monarchy for himself or anyone else, however. The problem was resolved by recognizing that if a presidency were created, Washington would surely fill the office. It was more or less openly decided it was safe enough to put Washington in the job and let him figure out what to do with it. Unfortunately, Washington was not immortal, was succeeded by a tumultuous Presidency of John Adams, and the nearly disastrous tied election of 1800. While it could be argued that the vagueness of his powers and duties in the eventual Constitution was a necessary concession to the ambiguous requirements of the Presidency of a new nation, the flaws of the Constitution's address of Presidential succession were careless in the extreme. History is replete with hundreds of examples of wars and assassinations associated with the succession of chief executives. For thousands of years, many societies have even concluded that the obvious flaws of hereditary kingship were to be preferred to the chaos which regularly results from trusting the personal ambitions of candidates to sort matters out.

So it was almost a foregone conclusion the new government would have a congress based on the republican model and a president. It was also clear that the British common law was about as good a judicial model as could be devised by any convention, and it had the universal allegiance of the legal profession. To start a new nation it is necessary to have a comprehensive system of laws from the very first day; Congress could later review and modify the common law to suit American needs. What then remained to be decided was the method of appointing judges, a question to which there seems to be no perfect answer in any state or nation. The lawyers in a jurisdiction know well enough who of their number is fair and learned, but it does not always suit their clients to argue before a fair and learned judge; clients only want to win their case. The public might elect judges impartially, but the public is seldom in a position to know the candidates, so it abandons the elections to the politicians. The politicians have their own agendas, and it is unfortunately not considered necessary in some districts for a politician to be impartial or even honest. To become a judge you have to ask who has the power to appoint you. And then you have to ask, what does that person want in return? In some districts, the answer is $100,000 in a campaign contribution. A person who agrees to that condition is not necessarily a bad judge when in office, but if he wants a promotion to a higher judgeship he has to ask the same question: who has the power to promote me, and what does he want? The judicial appointment question seems to have no good answer, but many American lawyers have been persuaded that the British system of the Inns of Court is superior. That system can be roughly summarized as sending a likely youth to "Judge School" in early adolescence and intoning Judicial ethics at him for the rest of his life in a judicial cloister. It must be recalled, however, that Margaret Thatcher hated the Inns of the Court system for some reason, and did her best as Prime Minister to abolish it.

Under the circumstances, the Constitutional solution to appointing judges is the most appealing alternative we have. First of all, the appointment of state and local judges is a matter left to the individual states to decide. Justices of the United States Supreme Court are nominated by the President, appointed by a vote of the Senate to serve for a lifetime, subject only to impeachment proceedings for bad behavior. The Chief Justice (not the President or anyone else in the Executive Branch) is the chief administrator of Federal Courts, which essentially imitate the appointment process of the Supreme Court. It is remarkable how useful a lifetime appointment can be. Insulated from political pressures, federal judges can expect to serve under several different political parties. Except in a few rotten boroughs permanently under one-party control, a politician in power can expect to have any judge he offends, still be a judge after the politician leaves office, but the reverse is usually not the case. Although the rules are different, the effect of lifetime appointment is much the same as lifetime cloistering under the British system, with the exception that it does not apply to the barristers representing clients, as it does in England.

So now we have approximated the three branches of government before the Constitutional Convention has even convened: a republican-style congress, an independently elected executive, and a lifetime judiciary. The genius of the Convention was what they did with this set of expectations.

Articles of Confederation: Flaws

DURING the twenty-five years (1776-1801) government was in Philadelphia, Americans who had rebelled against tight royal rule uncovered many defects in its opposite -- a loose association of states. Loose associations only preserve fairness by operating with unanimous consent, which is, of course, unfair to a thwarted majority, unless a dissenting minority thwarts itself as a gesture of kindness. The Founding Fathers ultimately devised a formula of weakening power by dividing it into layers -- national, state, county, municipal -- and seeking to confine minority dissent to the weakest political unit. Persuasion and peer pressure were given time to work up the ladder of appeal to a wider, more powerful body of citizens. Bottom upward by choice; top-down only in desperation. Furthermore, persuasion first, force as last resort. An implicit third safety valve emerged: if a good idea is smothered by a local concentration of bigotry, appealing to a wider population includes being heard by more viewpoints. No one claims to have authored this whole prescription or foreseen its hidden benefits; it apparently evolved by trial and error. There was another latent discovery for America's sparse population in a hostile wilderness: maintaining harmony was more essential than efficiency. It would be hard to consolidate more Quakerly concepts of governance in one document. Not exactly assembled, it emerged and was admired. The local Quaker merchants were living proof that harmony made riches for anyone, while force only works against weaker people. George Washington the cavalier general came to Philadelphia and gave it a softly Virginian twist, over and over: Honesty is the best policy. It seems to have originated in one of Aesop's Fables.

It is not necessary that the [Constitution] should be perfect; it is sufficient that [the Articles of Confederation are] more imperfect.

|

| James Madison |

Recently examined documentation reveals James Madison, the main theoretician of the closed-door Constitutional Convention, to have been severely contemptuous of state legislatures at this time in his life, and rather severely defeated by John Dickinson in a political quarrel in mid-convention about the powers of small states. From this fragile evidence emerges the idea that in balancing the powers of state and national governments in the "federal" system, it may have been someone else's idea that the greater freedom to move out of an offending state into a more favorable one, would appreciably restrain state legislative abuses. Even with this feature built into the system with the national government to enforce it, Madison is said to have been in a state of depression that the Convention refused to agree to his idea of giving Congress veto power over state laws. It took some time for improved transportation to strengthen this competition between states, but it may not be an accident that Delaware now leads the way in responding to the implicit opportunity.

Philosophy and history are different. The Framers gradually acknowledged a patched charter of tribal allegiance was insufficient and thus adjusted to the idea of a central government. They tweaked a decentralized model of governance to get the states out of the road, without antagonizing them so much they would not ratify it. Although it is commonplace to say the Articles of Confederation were a weak failure, the Articles did reflect American attitudes at the beginning of our formative period. The Constitution would not have been acceptable if the Articles of Confederation had not first been given a trial. By the end of the 1787 Philadelphia negotiation, the nature of the final proposal was to define a few absolutely minimum powers for a national government, identify a few other powers as destructive when in the hands of any other level of government, and leave a vast undefined area: where new and novel problems would be tried out in the states, then passed to a national level if necessary. Anticipating constant mid-course corrections was an important objective for even a minimalist Constitution, not the least of those challenges was to create ways to keep it minimalist. Simplicity itself keeps it hard to change. Starting at the bottom of the layers of government continues to this day to introduce new and unexpected problems to the "laboratory of the states" or even lower, working upward only as proven necessary, or spread nationally only after the solution is highly successful. It is a legacy of slavery, the Civil War, and direct election of Senators (Amendment XVII) that many Americans still fail to welcome the merits of this approach, or lack the patience to try it for their pet ideas. Considering the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution as two documents with continuous goals, we got it right, the second time.

And we got it right in the environment of Eighteenth-century Quaker Philadelphia, where a tolerant examination of new ideas was more venerated than in any other place in the civilized world. With a combination of wisdom and impasse, minor issues were left to the future. It is true this sometimes creates problems of neglect. But it makes it possible to define those few issues which must never change. An unexpected virtue of minimalism surfaced eighty years later: many men understood it well enough to die for it.

|

|

Edwin Corwin's "John Marshall and the Constitution" |

Much has been written about the separation and balance of powers between the three branches of the federal government. However, the real balance of power in the Constitution in 1787 was vertical, between the central government and the constituent states. Balancing power horizontally, within the central government's branches, is a way of preventing one side of this other argument from tilting the state/federal balance in its own favor, or slowing down the effect of any victories by one side. In other words, it preserved citizen liberty to choose. From this continuing two-dimensional struggle emerges the explanation for filibusters, the seniority system, the confirmation process for Supreme Court and Cabinet appointments. It also calls into question the Seventeenth Amendment, where the state legislatures lost the power to appoint U.S. Senators. In 1786 the states had all the power, in 2009 state power is much diminished; but it is not entirely gone by any means. It is true the cry for states rights, essentially an appeal to the Deity for Justice is futile. If states are to wrest power back from the federal government, it will be by the adroit exercise of powers buried within the balanced powers of the federal branches, but it can succeed if the public ever wants it to succeed. The Framers seem to have overlooked the possibility that federal power could someday outgrow its blood supply, simply growing too big to manage. It is also true the Framers neglected the possibility of a protracted period of disagreement between two halves of the electorate. At least in these particulars, there is room for the further evolution of the Constitutional principle.

While features of the present Constitution can sometimes be linked to the correction of flaws in the Articles, one by one amendment never seemed to be quite enough. Subsequent analysis of Original Intent has often had to contend with the unspoken intent of earlier negotiators to strengthen partisan advantage in later struggles. The political battles being fought at the beginning, which except for slavery are substantially the same today, were sometimes being promoted for reasons which now seem merely quaint. Fine, everyone can agree it was complex. Still, there was a recurring uneasiness: what was the underlying flaw in the Articles? What, as they say, is the take-home point?

One widely accepted summary, probably a correct one, of what was centrally wrong with the Articles of Confederation, lies in a concise observation, which follows, from Edward S. Corwin's book John Marshall and the Constitution:

"The vital defect of the system of government provided by the soon obsolete Articles of Confederation lay in the fact that it operated not upon the individual citizens of the United States but upon the States in their corporate capacities. As a consequence, the prescribed duties of any law passed by Congress in pursuance of powers derived from the Articles of Confederation could not be enforced."

And that's how many Revolutionary Americans, possibly most of them, had wanted to have it. They were in revolt against all strong government, not just the King of England. They surely would have applauded Lord Acton's declaration that "All power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Thirteen years of near-anarchy taught them they must at least give some limited powers to a central government, but it was to be no more than absolutely necessary. For some, the Ulster Scots, in particular, even the absolutely minimum amount was still just a bit too much. In effect, these objectors wanted a democracy, not a republic.

To deconstruct Professor Corwin's analysis somewhat, the equality-driven followers of Thomas Jefferson believed the insurmountable obstacle for uniting sovereign states is that they are sovereign, and won't give it up. The merit-driven followers of Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris, and George Washington bitterly resisted; in business and in war you need the best leaders to rise to power. The function of common men is to select the best among themselves to be leaders. Only James Madison seems to have grasped that ideal government might tend more toward a republic for purposes of the enumerated federal powers plus enumerated powers specifically denied to the states. For lesser issues, perhaps a purer democracy would be just as workable. However, in operation, it took scarcely a year to discover that the common man would not automatically select the best man he knew to be his representative. In fact, there exists a considerable populist sentiment, that wealth and success outside government are actually disqualifications for office. To some extent, this reverse social Darwinism is grounded in an unwillingness of the upper class to serve in government, perhaps because service to the country interferes with the lifestyle of unrestrained power and wealth which other occupations allow, but is forbidden to public servants. In any event, we persist in the fruitless argument whether America is a democracy or a republic; it was designed to be a mixture of both. Within the time of the first presidency, the unattractive realities of mixing human nature with elective politics transformed the meanings of the Constitutional document to something that was never written there, and other nations have largely failed to grasp. It apparently also worked a major transformation in its main author. James Madison first quarreled with his ally, Alexander Hamilton, and joined forces with the Constitution-doubter Thomas Jefferson. His mentor and idol, George Washington, essentially never spoke to him again.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

States rights no longer confronts America directly, because the Founding Fathers managed to get around it until the Civil War, and then the Fourteenth Amendment enabled the federal judiciary to attenuate state sovereignty somewhat further without eliminating the architecture of a federation of states. In other words, in two main steps we deprived the states of some sovereignty, but no more than absolutely necessary, and we took more than a century to do it. The European Union currently faces the same obstacle; this is how we solved it. If they can get the same result in some other peaceful way, good luck to them. Our framers used the language "Congress may...or Congress may not..." They only dared to strip state legislature of a few powers because they needed the legislatures to ratify the Constitution, a gun you can only fire once. Thus, they forbade states the right to issue paper money, the power to interfere in private contracts, and such, as enumerated in Article I, Section X, where the operative phrase is "The states are forbidden to..". The framers were willing to strip the unformed Congress of many more specific powers than the all-too-existing states; the Constitution can be read as a proclamation of the powers which any central government simply must possess. There might be other desirable powers, but here is the minimum. After eighty years, individual Southern states asserted their unlimited powers extended to nullification and secession, and because of a perceived need to preserve slavery would not back down. The Constitutional consequence of this national tragedy was the Due Process section of the Fourteenth Amendment, which has since been purported by the Supreme Court to mean that whatever the federal government may not do, the states may not do, either. However, Due Process traces back to the Magna Carta and has been so tormented by an interpretation that for the purpose stated, it is growing somewhat too elusive to remain useful. For historical reasons, we never gave a fair trial to the original proposal to address the federal/state dilemma. The Constitutional Convention was held in confidence, many delegates changed their minds along the way, and many ideas were more perceived than enunciated. It is plausible that the original strategy originated with Madison's teachers and emerged from many discussions, but there were several delegates in attendance with the sophistication to originate it. In a convention of egotists, there were even a few who would put their ideas in someone else's mouth.

The concept of how to curtail power in a non-violent way, can be called Regulatory Competition. Mitt Romney seemingly plans to promote the idea as a central feature of his political run for President of the United States, using a variant he has developed with Glenn Hubbard, the Dean of the Columbia University School of Business. The idea does still work reasonably well with state taxes and corporate regulation. If a state raises a tax, estate tax for example, in a burdensome way, people will flee to a state with more reasonable taxation. Corporations have learned how to shift legal headquarters to Delaware and other states which court them, and in really desperate cases will move factories or whole businesses. There is little doubt this discipline is effective, and little doubt that some cities and states have been punished severely for encouraging an anti-business environment. Whether the Fourteenth Amendment could be cleverly amended to expand this competitive effect without reintroducing segregation or the like, has not been seriously considered, but perhaps it should be. There are however not too many alternatives to consider.

As far as advising our European friends is concerned, it would be important to point out that the original version of Regulatory Competition completely depends for its effectiveness on the freedom to flee to some other state within the union. A common language is a big help to unity, but the ability to move residence is essential, so for practical purposes, both a common language and freedom of migration are required. Underlying such concessions is a sense of tolerance of cultural differences. That is unfortunately where most such proposed unions have either resorted to violence or failed to unite. And of course, the power which might otherwise be abused must then be shifted from the federal, back to a state level. What surfaces is a sort of one-way street? It remains far easier to devolve into little statelets than to unite for the benefits of scale. A working majority under the likes of Thomas Jefferson might have been assembled in the Nineteenth century but was held back by coping with the expanding frontier. During the Twentieth century, it would have been held back by the need to deal with world power. The Second Tea Party seems to have some inclination along these lines, but it remains to be seen whether some overwhelming need for world power will once more overcome the obvious national ambivalence about it.

The revised proposal for the regulatory competition takes the proposal to a different level, possibly a more workable one. Workers in the United States can freely move from one state to another but are restrained by national laws from equally free movement between nations. Removing that barrier makes the European Union attractive, although it inflames local nationalism. Since it seems more palatable to allow the currency to move, perhaps a little tinkering would be sufficient to permit uniform monetary rules to be the hammer which forces nations into permitting free trade on a global scale. The people themselves can remain at home in their national costumes, perhaps perfecting their religions in more churches and language skills in more schools. Meanwhile, the insight of Adam Smith would prevail for the long-term prosperity of everyone. Each party in a transaction feels enriched by it, the seller preferring to have the money, and the buyer preferring to own the goods. Multiplied a trillion-fold, these improvements in everyone's condition result in the steady enrichment of all.

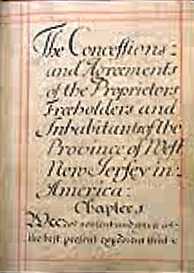

Concessions and Agreements

|

| Concessions and Agreements |

The United States Constitution is a unique achievement, but it had significant precursors, many of which James Madison had studied at Princeton. In the days of difficult ocean travel, almost all colonies were bound by an agreement to maintain loyalty to their European owners in spite of receiving latitude to govern themselves. Charters and documents defining these roles were generally written by the owners, and the colonists could pretty much take them or leave them. In the case of New Jersey in 1664, however, a very formidable lawyer and friend of the King named William Penn was drawing up agreements to his own conditions of sale, taking care that the grant of governing authority he received was favorable. Penn's relationship to the King was unusually good, to say the least. He had more reason to be wary of nit-pickers in the King's administration, trying to anticipate every conceivable disappointment for some successor King.