0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Howard Hughes, Swashbuckler

New topic 2019-01-09 20:07:02 description

World War I's Only True Winner

America’s military involvement in World War I was not a given. Only in April 1917, after three years of warfare in Europe and renewed U-boat attacks on American shipping, did President Woodrow Wilson ask Congress to declare war on Germany. At the time, the U.S. Army was sorely lacking— 200,000 lax regulars and 400,000 National Guard troops more suited to quelling labor strife than engaging in deadly trench warfare. Eventually, three million men would be drafted into a total a force of almost four million, many of them first-generation immigrants, including Germans still speaking their native tongue.

By the time of America’s decision to enter the war, the collapse of czarist Russia in the east had enabled Germany to augment its depleted western ranks with an additional million troops. Germany hadn’t achieved its visions of empire, but a decisive blow before the Americans could arrive in force might allow it to garner a favorable armistice and ensure its standing among the major powers.

SONS OF FREEDOM

By Geoffrey Wawro

Basic, 596 pages, $35

NEVER IN FINER COMPANY

By Edward G. Lengel

Da Capo, 358 pages, $28

In “Sons of Freedom: The Forgotten American Soldiers Who Defeated Germany in World War I,†Geoffrey Wawro, a professor of history and director of the Military History Center at the University of North Texas, states forcefully: “Had the Americans not entered the war and deployed two million troops to France, the Allies would almost certainly have lost†and “the global balance of power would have tipped heavily in Berlin’s favor.†He admits that the strength of his conclusion surprised even him and that he came to it only after extensive research in the national archives of the belligerents.

In the spring of 1918, Gen. Erich Ludendorff orchestrated a series of German offensives to divide and defeat the worn-out British and French armies. Midway through these offensives, German troops got a taste of a new fury. The American 1st Infantry Division, soon the storied “Big Red One,†attacked at Cantigny in northern France. “It was,†Mr. Wawro notes, “the war’s first American attack delivered with courage and precision, and it was the only Allied offensive operation at a time when the British and French were barely holding on.â€

More came quickly. As Ludendorff aimed for Paris in what became the Second Battle of the Marne, Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, deployed the newly arrived U.S. 2nd and 3rd Divisions to stop the German assault at Château-Thierry, a town on the Marne River, and a nearby forest called Belleau Wood. The attackers were stunned by the ferocity of the American resistance. “Without the Americans,†many German officers insisted, “we would have been in Paris by July.â€

Ludendorff accelerated the timing of his final offensive—“the Peace Offensiveâ€â€”in hopes that it would encourage an armistice before more Americans entered the lines. But once opened, there was no turning off the American spigot. By the late summer of 1918, 1.2 million American troops were in France, with 250,000 more arriving every month.

Their learning curve was steep. Training was frequently cut short, and experience had to be gained in place. Across a barbed-wire-laced maze of trenches, baptisms under fire were abrupt and deadly, coming from the new weaponry of poison gas, machine guns, airplanes and heavy artillery. Artillery, including a battery commanded by Capt. Harry Truman, rarely seemed to be in the right place. Tanks commanded by Lt. Col. George Patton suffered mechanical breakdowns or tumbled into ditches.

But out of this crucible came competence that proved decisive in what came to be called the Hundred Days. With Ludendorff’s offensives thwarted, Pershing consolidated his divisions into an all-American sector near Verdun on the eastern end of the Allied line. While questioning some of Pershing’s tactical skills, Mr. Wawro nonetheless credits his relentless commitment to keeping the U.S. Army together under one command rather than parceling its units out as replacements to the British and French. Ultimately, American success in this sector would seal the fate of the German army.

Pershing and his “doughboys†beat back a threatening bulge in the German lines at Saint-Mihiel and then turned north, intent on cutting key rail lines that fed and supplied German troops farther west. The American line of attack pointed straight toward dense German defenses between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River.

Once the Meuse-Argonne offensive got underway on Sept. 26, 1918, it was all or nothing. There were no stopping places. Lamenting the bristling defenses arrayed against them, one doughboy swore: “Every goddam German there who didn’t have a machine gun had a cannon.†Throughout his narrative—both a stirring story and a careful work of military history—Mr. Wawro is adept at explaining tactics and keeping generals and units on both sides straight.

Newsletter Sign-up

Among the units attacking headlong into the Argonne Forest was the 77th “Metropolitan†Division. Few stories are as well known as that of the 600 men from the division who found themselves, in the first week of October, cut off from their lines. They became “the lost battalion.†In retelling their story in “Never in Finer Company: The Men of the Great War’s Lost Battalion,†Edward G. Lengel, whose books include “To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918†(2008), focuses on the ranking officer, Maj. Charles Whittlesey, and his steady second in command, Capt. George McMurtry.

Whittlesey was a scholarly New York attorney more at home peering through thick eyeglasses at law books than at enemy trenches. McMurtry was a stockbroker whose solid build attested to the prep-school boxing champion he had been. Both men had volunteered for a reserve officer training program before America entered the war.

Recruited from the sidewalks of New York, the 77th Division was “almost ridiculous†in its diversity, Mr. Lengel writes. There were “Jews (one out of every four men, according to a census), Chinese, Poles, Italians, Irish, Greeks, Russians, Germans, and Anglo-Saxons.†The only New Yorkers missing, he notes, were African-Americans, barred by the Army’s segregation policies. (Many New York blacks did, however, serve in the segregated 93rd Division’s regiment of “Harlem Hellfighters.â€)

Maj. Gen. Robert Alexander, in command of the 77th Division barely a month, was explicit in his orders: Push forward; ignore your flanks; focus on the objective. Whittlesey and his doughboys did just that and became not so much “lost†as outflanked and surrounded by German troops. Entrapped in the Argonne’s tangle of deep ravines, they faced a nightmare of pounding artillery bombardments (some from friendly fire), rattling machine guns, scarce water, little sleep, and no food. Men died outright; others succumbed to wounds after excruciating days. When relief finally arrived a week later, Whittlesey and McMurtry counted only 194 men, of the original 600, who had escaped the woods with them.

Shell-shocked by the loss of so many under his command, Whittlesey committed suicide three years later. McMurtry lived to the age of 82, dying in 1958, but he seemed to carry Whittlesey’s burden as well as his own. “As long as you and I live,†McMurtry told gatherings of Lost Battalion survivors, “we will never be in finer company.â€

That could be said of all who served in the Meuse-Argonne during that bloody autumn. “The three weeks after October 10,†Mr. Wawro writes in “Sons of Freedom,†“were the grittiest of the war, the Germans throwing in the last of their first-class divisions . . . and the three American corps measuring their daily advances in yards.†The Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery holds the largest number of American dead of any military cemetery in Europe.

Then, rather suddenly, it was over. British and French attacks all along the Allied lines had driven the Germans back, but it was the American thrust on the Meuse-Argonne front that threatened to surround a goodly portion of the German army. Faced with a similar collapse on the Austro-Hungarian front and widespread unrest at home, Germany once again looked for an armistice. Britain and France accepted Germany’s plea because they sensed that time was running out on their side, too.

America’s European allies “knew America had saved them,†Mr. Wawro writes, “but they deplored the political cost and its vast ramifications.†The Yanks that the British and French desperately needed in 1917 had crossed the ocean in force and become the trans-Atlantic power to be reckoned with in 1918 and beyond. “The world,†Mr. Wawro concludes, “would never be the same again.â€

—Mr. Borneman’s “Brothers Down Pearl Harbor and the Fate of the Many Brothers Aboard the USS Arizona†will be published in May.

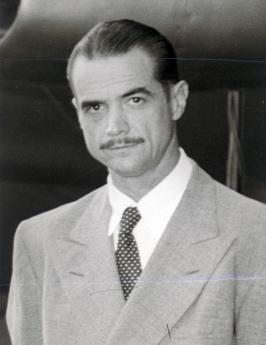

Inside the Star Factory

The life of Howard Hughes is a 20th-century story; airplanes, money, movies, and sex. It’s usually presented as an enigmatic tragedy when it might play better as a rollicking Preston Sturges comedy. In her book “Seduction†Karina Longworth finds her own unique purpose for Hughes’s adventures: “It’s time,†she writes, “to rethink stories that lionize playboys†and “one way to begin†is to study “a playboy’s relationship with some of the women in his life from the perspective of those women.†This worthy purpose creates a book with two parallel tracks: one about Hughes and one about the lives and works of women in film. Ms. Longworth attempts to connect the biography of Hughes (1905-76) to the modern world of #MeToo awareness, a dubious scholarly idea but certainly a commercially viable (and highly readable) one.

The author of books on George Lucas, Al Pacino, and Meryl Streep, Ms. Longworth is the creator and host of the popular podcast “You Must Remember This,†for which she uses her prodigious research skills to present “the secret and/or forgotten histories of Hollywood’s first century.†The Hughes story is neither secret nor forgotten, having been covered in a fake autobiography by Clifford Irving in 1972, discussed in countless magazines (from Time to Confidential to Fortune to Modern Screen), reimagined in movies by Jonathan Demme (“Melvin and Howardâ€) and Martin Scorsese (“The Aviatorâ€), and chronicled previously by various authors (including his long-time business associate Noah Dietrich).

SEDUCTION

By Karina Longworth

Custom House, 543 pages, $29.99

Thus the freshest—and most interesting—parts of “Seduction†are those where Ms. Longworth refutes the idea that there were no women working in key jobs in early Hollywood. She presents Hollywood “as a place where women could immigrate in search of legitimate work and do it without the help or chaperoning of men.†She’s right. When the film was officially born in 1895, it wasn’t a boy. It’s long past time for the history of the medium’s women pioneers to be written: This book isn’t that, but Ms. Longworth could write it if someone would let her.

The author is a dedicated film historian, and in “Seduction†her basic love for Hollywood and its motley crew of shysters and stars is on full display. She uses Hughes’s entire life—not just his relations with women—as a platform from which to jump off into areas of historical interest. A discussion of Hughes’s magnum directorial opus, “Hell’s Angels†(1930), corrects the exaggerated idea that sound ruined the careers of most silent stars. His production of the violent “Scarface†(1932) allows her to explain the demarcation between pre-Code and post-Code censorship. His relationship with Ginger Rogers veers off into a lengthy (and terrific) discussion of the film “Kitty Foyle†(1940), for which Rogers won an Oscar. Ms. Longworth says Rogers “is remembered as a trouper†but also was a woman “who believed in the ritual of marriage†(she believed in it so much she went through it five times). When Hughes takes up with Katharine Hepburn, Ms. Longworth puts the much quoted “box-office poison†label into accurate perspective, calling it “a work of hyperbolic propaganda.â€

Ms. Longworth makes a strong statement about not caring about the scandal from the past (“I don’t think it mattersâ€), but she supplies plenty of it, some of which is connected to Hughes and some of which isn’t. She is at her best writing about specific movie stars and specific films, such as the bizarro noir delight “His Kind of Woman†(1951), which she says Hughes “put his special touch on†and boasted was his best picture. (Ms. Longworth says “the boast was accurate.â€) She describes Jane Russell, a successful Hughes protégée and star of his controversial “The Outlaw†(1943), as “a female Robert Mitchum,†saying the sultry and bosomy Russell was “Howard’s idea of the girl next door.†She assesses Terry Moore, a second-string starlet who in the 1940s and ’50s claimed to be Hughes’s wife, as “uniquely talentless.†She even dares to criticize America’s sacred cow, Hepburn herself, pointing out that Hepburn carved out her “level of liberation . . . thanks to her alliances with powerful men.†Ms. Longworth knows her stuff, although there are occasional minor errors. (For instance, K.T. Stevens was not the daughter of director George Stevens, but of director Sam Wood. Errol Flynn’s statutory rape trial was in 1943, not 1934.)

Howard Hughes was born in Texas, the son of a man who grew rich selling drill bits and other tools to oilmen. Hughes inherited his family’s considerable wealth at age 18 and took it to Hollywood in 1925. Ms. Longworth calls him “a failure as both an artist and a mogul.†She sees him as a seducer, an abuser of male power. Although famous for relationships with the great beauties of his era (movie stars Billie Dove, Rogers and Hepburn, Ava Gardner and others), he married only twice—first in 1925 to a Houston girl of good family, Ella Rice, and then, in 1957, to a beauty-contest winner from the Midwest, Jean Peters, who had become a successful star briefly in the late 1940s.

Newsletter Sign-up

As he aged, Hughes became known for “sponsoring†young females he hoped to turn into stars, signing them to contracts and keeping them as virtual prisoners held hostage to his whims. One of these women, Faith Domergue, never made it to the top and spent her youth captive to Hughes’s control. He kept a stable of informers, security guards and private detectives to spy on her, causing her to retaliate. In 1943 Domergue, tooling around Hollywood in a little red car Hughes had given her, spotted him driving his big black Buick with the gorgeous Ava Gardner sitting beside him. Domergue viciously rammed them, smugly saying later that “poor little Ava seemed to bounce up and down in her seat like a yo-yo.†(This surely has to be the only time anyone ever referred to Gardner as “poor little Ava.â€) Domergue—with a straight face—once said Hughes told her, “You are the child I should have had.â€

Ms. Longworth does not ignore the serious accomplishments of Hughes’s life. He was a man of innovation, intelligence, and enterprise. Besides running an enormous business empire and designing airplanes (and cantilevered brassieres), Hughes earned his pilot’s license in 1928. By 1933 he set a world land speed record and in 1936 a record nonstop transcontinental flight time. In 1946 he flew the test flight of the XF-11 he had designed for the government, crashing spectacularly in a near-fatal disaster.

“Seduction†carefully traces the ups and downs of Hughes’s career over decades that culminated in his personal decline. Ms. Longworth pinpoints 1942 as the year his workaholic habits began to become “unsustainable.†By late 1944, he began exhibiting “obsessive-compulsive tics.†Ms. Longworth pinpoints a July 1948 Time magazine cover story as the moment in which Hughes started to “lose control of his own story.†His behavior was erratic during his years as head of RKO, the movie studio he purchased in 1948 and sold in 1955; he became an “increasingly eccentric†mega-millionaire who had “become obsessed with eradicating Communists.†After his sale of RKO, Hughes receded from the public eye, and Ms. Longworth makes clear why she thinks he withdrew: a decline in both physical and mental health; head injuries suffered in plane crashes, especially the near-fatal one in 1946; the loss of his identity as a lone wolf after he married Peters; and the 1957 business resignation of Noah Dietrich, his reliable friend and business sidekick since 1925.

Ms. Longworth sheds as much light on Hughes as probably can be shed. She shrewdly calls him a man who knew that “the gap between perception and reality could be made to disappear.†As early as 1947 Time described Hughes as “the Hollywood playboy and planemaker about whom the public has heard very much but actually knows very little.†It’s an evaluation that’s still valid.

—Ms. Basinger is chairwoman of the department of film studies at Wesleyan University and the author, most recently, of “I Do and I Don’t: A History of Marriage in the Movies.â€

Swashbuckler

|

| Howard Hughes |

In 1947, Howard Hughes was summoned to Washington to testify at a Senate hearing. Claude Pepper, Democrat of Florida, was in the chair, clearly angry about Hughes' conduct of munitions contracts, including flagrant non-performance. Three wooden flying boats had been commissioned for $18 million but not produced, people had been killed in crashes of test planes, and the newspapers were full of obscure allusions to unspecified wrong-doing in high places. Although the Hughes hearings were front page news for weeks, in those days it was only necessary to walk in and sit down if you wanted to watch them.

Under the circumstances, it would have been understandable if Hughes had been reduced to a trembling mumbler, probably advised to "take" the Fifth Amendment with every question. Congressional chairmen, particularly Claude Pepper,

|

| Claude Pepper |

quite regularly grandstand and bully the helpless witness at hearings like this, since it portrays them to the voters as heroic defenders of the public interest, and could even forward their chances of becoming a Presidential candidate. Hughes the scapegoat seemed to be in for a public flogging. The first step was to haul him before the committee and then keep him waiting for an hour or so, while the members attended to important public business, maybe even had to go for a roll-call vote or something. You could tell that things were not going according to the usual script when Hughes himself arrived quite late, accompanied by quite a large staff or retainers. When Pepper still delayed the hearing, Hughes called for a newspaper and elaborately read the comic pages.

The Texas swashbuckler didn't look the part. His accent and tailoring reflected a New England boarding school, and while his mustache resembled that of his friend Errol Flynn, he had a voice like a lion and lightning retorts that would do credit to Bill Buckley. Reminding the Chairman that he had been deafened in the crash of a racing plane, he asked him to repeat the question. Sorry, please repeat it again. And again, and again. Pepper was beside himself.

|

| The Spruce Goose |

Flustered, Pepper tried to reverse the treatment. Senator, I have already answered that question. Well, answer it again. No, I stand on my previous testimony. I forget what you said. Have the stenographer read it to you. Her transcript is not complete. Very well, my own secretary will read it back to you.

|

| Glomar Explorer |

As if to demonstrate that he hadn't defrauded the government, Hughes, who always test-piloted his own planes, flew the H-4 about a mile in less than a minute during what was supposed to be a taxiing test on November 2, two months after his congressional testimony.

In another strange and unexplained footnote, the Glomar Explorer was a ship built in Philadelphia and used in Project Jennifer in an attempt to salvage a sunken Russian nuclear submarine and discover any secret technology it might contain. This was long past the time when Hughes was supposed to be disgraced and banished from Government contracts. The Senate hearings obviously had no effect on his status, and indeed might even have been entirely staged to mislead the Russians and others. Like so many things in his life, this episode has no readily obvious explanation.

Only in retrospect is it possible to see that Hughes was involved in lots of top-secret matters, and the bravado of his defiance -- not to say contempt of Congress -- might have had roots in some sure knowledge Pepper would not dare touch him. The CIA commissioned him to build the Glomar Explorer to find a sunken Russian submarine, using a phony story of manganese recovery. The supposed political victim of the much later Watergate break-in, Larry O'Brien, is said to have once been a Hughes employee; on the other hand, Hughes was very close to the Nixon Administration. There were inevitably many ties between his Las Vegas gambling empire and Cuban underworld figures, as well as Hollywood figures. Hughes was an owner of the Dallas movie theater where John Kennedy's murderer Lee Oswald tried to hide and was captured. It is not possible to judge Howard Hughes by the usual standards; this eccentric billionaire was capable of doing unimaginable things and it will be remarkable if spectacular news about him ends with his death.

Show Biz Image: Hepburn, Rogers, Kelly

A fair lady's image depends, Bernard Shaw told us, not on how she acts, but on how she is treated. The case in point is a beautiful Main Line heiress in The Philadelphia Story, who can choose any man she wants. What she cannot do, is escape grief for a wrong choice.

When Broadway and Hollywood paint your image, not believing your own press releases takes strength. Toward the end of the Great Depression around 1938, show business turned full and nasty attention to Philadelphia high society. Earlier, while author Christopher Morley was at Haverford College, Katharine Hepburn at Bryn Mawr College, and Grace Kelly at school on Schoolhouse Lane, Hollywood had picked up just enough authentic detail to be dangerous. Kitty Foyle and The Philadelphia Story are two fairly accurate snapshots of a complex society, but one cannot be fully understood without the other. Indeed, the real-life trivialities of Howard Hughes, Katharine Hepburn, Grace Kelly, and Ginger Rogers sharpen the outlines of the graceful gentlefolk they attempted to portray.

In 1938, Hepburn was a smash hit on Broadway with Philip Barry's Philadelphia Story, which essentially tells of the agonized turmoil of a Main Line princess, facing a three-way choice between a charming but worthless blue-blood, a self-made dullard, and a poor but noble New York magazine writer. (Just guess who the author was rooting for.) In real life, of course, Ms. Hepburn chose to spend four years with movie producer Howard Hughes the dare-devil Texan with a hundred starlets in his bedroom. Most of her competitors wanted a movie contract and/or a diamond bracelet, but Katy wanted the movie rights for Philadelphia Story, which Howard readily bought for her. Although other actresses played the role, she made herself into the image of a Philadelphia heiress, thereby nudging that Main Line image toward her own. At the time the image did not include much mention of Howard Hughes or actor Spencer Tracy, another long-time companion.

|

| Ginger Rogers |

Meanwhile, Ginger Rogers, who was also engaged to Howard Hughes at one point, was making a great name for herself as the star of Christopher Morley's Kitty Foyle. Morley's Haverford experience taught him somewhat more respect for the Philadelphia Gentleman than Barry ever had, while his experience at the Curtis Publishing Company also made him appreciate the smart and plain-spoken Philadelphia girls from working-class districts. Highborn Philadelphia women are only sketchily imagined by Morley, except they somehow fail to appeal to his manly fictional cricket-player from the Main Line.

As matters turned out, Katy lost to Kitty. Although Hepburn was surely the more talented actress, eventually winning five Academy Awards, Ginger Rogers walked away with the 1940 Oscar for her interpretation of a working-class Philadelphia lady. Either way it turned out, of course, Howard Hughes was bound to be a happy fellow.

|

| Grace Kelly |

And yes, in 1956 Grace Kelly was the star of High Society, a renamed version of the Philadelphia Story for which, remember, Katherine Hepburn still controlled the rights. The film was a mediocre performance, just a little short of embarrassing. But however inexact all three of these portrayals may have been, there is little doubt that Philadelphia society moved a bit in their direction, involuntarily living up to an image created by three observers who seemed to their own observers to retain hostility traceable to their own undefined turmoils.

Philip Barry stacks the deck somewhat, portraying the leading lady as movie audiences during the Depression were likely to fantasize, indulging a luxury only a rich girl would supposedly be careless about. She rejects the colorless rich suitor out of hand. But while her remaining choice between a charming magazine writer and a charming playboy is made to seem a closer call, it really never makes our Philadelphia Cleopatra hesitate very long. In the single editorial comment, the play's author permits himself, is tucked the snarl, "She's a lifelong spinster, no matter how many times married." That's New York talking. Bitter, bitter.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class: E. Digby Baltzell ISBN-13: 978-0887387890 | Amazon |

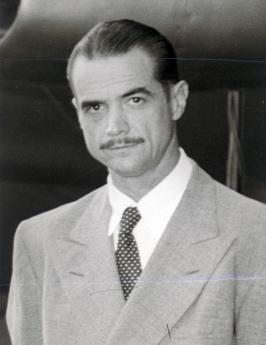

Evo-Devo

|

| The Franklin Institute of Philadelphia |

THE oldest annual awards for scientific achievement, probably the oldest in the world, are the gold medals awarded by the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia for the past 188 years. Nobel Prizes are more famous because they give more money, but that in a way involves another Philadelphia neighborhood achievement, because Nobel's investment managers have run up their remarkable investment record while operating out of Wilmington, Delaware. In the past century, one unspoken goal of the Franklin Institute has been to select winners who will later win a Nobel Prize, the actual outcome more than a hundred times. That likelihood is one of the attractions of winning the Philadelphia prize, but in recent years some Nobel awards have acquired the reputation of being politicized particularly the Peace and Literature prizes. Insiders at the Franklin are positively fierce about avoiding that, so the Franklin Institute prizes have become known for recognizing talent, not merely fame.

|

| Dr. Jan Gordon, Dr. Sean Caroll, and Dr. Cliff Tabin |

Within Philadelphia, the annual awards ceremony is one of the four top social events. The building will seat 800, but reservations are normally all sold out before invitations are even put in the mail. A major source of this recent success is clear; in the past twenty-five years, the packed audience is a star in the crown of Dr. Janice Taylor Gordon. This year, she hurried back from a bird-watching trip in Cuba, just in time to busy herself in the ceremonies where she sponsored Dr. Sean Carroll of the Howard Hughes Foundation and the University of Wisconsin, for the Benjamin Franklin medal in the life sciences. Carroll's normal activities are split between awarding $80 million a year of Hughes money for improving pre-college education from offices in Bethesda, Maryland, and directing activities of the Department of Genetics in Madison, Wisconsin. His prize this year has relatively little to do with either job; it's for revolutionizing our way of thinking about evolution and its underlying question, of how genes control body development in the animal kingdom. Evolution and Development are academic terms, familiarly shortened to Evo-Devo.

|

| Dr. Carroll's Butterflies |

My former medical school classmate Joshua Lederberg, also a resident of Philadelphia, was responsible for modern genetics, demonstrating linkages between the DNA of a cell, and the production of a particular body protein. For a time it looked as though we might confidently say, one gene, one protein, explains most of the biochemistry. In the exuberance of the scientific community, it even looked as though deciphering the genetic code of 25,000 human genes might explain all inherited diseases, and maybe most diseases had an inherited component if you took note of inherited weaknesses and disease susceptibilities. But that turned out to be pretty over-optimistic. Lederberg got into an unfortunate scientific dispute with French scientists about bacterial mating and now appears to have been wrong about it. But the most severe blow to the one gene, one protein explanation of disease came after the NIH spent a billion dollars on a crash program to map out the entire human genetic code. Unfortunately, only a few rare diseases were explained that way, at most perhaps 2%. Furthermore, all the members of the animal kingdom turned out to have pretty much the same genes. Not just monkeys and apes, but sponges and worms were wildly different in outward appearance, but substantially carried the same genes. Even fossils seem to show this has been the case for fifty million years. Obviously, animal genes have slowly been added and slowly deleted over the ages, but in the main, the DNA (deoxynucleic acid) complex has remained about the same during modest changes in evolution. Quite obviously, understanding the genome required some major additions to the theory's logic.

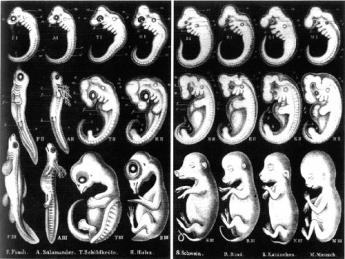

In late 1996, three scientists met in Philadelphia for a brain-storming session. Sean Carroll had demonstrated that mutations and perhaps an evolution of the wing patterns of butterflies and insects took place during their embryonic development, and seemed to be controlled by the unexplored proteins between active genes. Perhaps, he conjectured, the same was true of the whole animal kingdom. Gathered in the Joseph Leidy laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania, the three scientists from different fields proposed writing a paper about the idea, suggesting how scientists might explore proving it in the difficult circumstances of nine-month human pregnancies, in dinosaurs, in deep-sea fish and many remote corners of the animal kingdom. Filling yellow legal pads with their notes, the paleontologist (fossil expert) Neal Shubin of the University of Pennsylvania, genetic biologist (Sean Carroll of Wisconsin), and Harvard geneticist Cliff Tabin worked out a scientific paper to describe what was known and what had to be learned. The central theme, suggested by Carroll, was that evolution probably takes place in the neighboring regulatory material which controls the stage of life early in the development of the fetus, and these regulatory proteins consist of otherwise inactive residual remnants of ancient animals from which the modern species had evolved. As the fetus unfolds from a fertilized egg into a little baby, its outward form resembles fish, reptiles, etc. And hence we get the little embryonic dance of ancient forms morphing into modern ones. In deference to the skeptics, it would have to be admitted that the physical resemblance to adult forms of the ancient animals is a trifle vague.

|

| Haeckel's drawings of vertebrate embryos, from 1874 |

Embryologists have long argued about Ernst Haeckel's incantation that "Ontology recapitulates phylogeny", which is a fancified way of saying approximately the same thing. Darwin's conclusion was more measured than Haeckel's and explanations of the phenomenon had been sidelined for almost two centuries. But it seems to be somewhat true that fossils which paleontologists have been discovering, going back to dinosaurs and beyond, do mimic the stages of embryonic development up to that particular level of evolution, and might even use the same genetic mechanism. The genetic mechanism might evolve, leaving a trail behind of how it got to its then-latest stage. Borrowing the "Cis" prefix ("neighboring") from chemistry, these genetic ghosts have become known as Cis-regulatory proteins as the evidence accumulates of their nature and composition. Growing from the original three scientists huddled in Shubin's Leidy Laboratories in 1996, academic laboratories by the many dozens soon branched out, dispatching paleontologists to collect fossils in the Arctic, post-doctoral trainees to collect weird little animals from the deserts of China, and the caves of Mexico, everywhere confirming Carroll's basic idea. Even certain forms of one-celled animals which occasionally form clumps of multi-celled animals have been examined and found to be responding to a protein produced by neighboring bacteria which induces them to clump -- quite possibly the way multi-cellular life began. Many forms of mutant fish were extracted from caves to study how and why they developed hereditary blindness; the patterns of markings on the wings of butterflies were puzzled over, and the markings on obscure hummingbirds. The kids in the laboratory are now having all the fun with foreign travel, while the original trio finds themselves spending a lot of time approving travel vouchers. Many fossils of animals long extinct have been studied for their evolution from one shape to another, especially in their necks, wings, and legs. Some pretty exciting new theories emerged, and are getting pretty well accepted in the scientific world. At times like this, it's lots of fun to be a scientist.

5 Blogs

World War I's Only True Winner

New blog 2019-01-09 20:02:02 description

Inside the Star Factory

New blog 2019-01-09 20:13:36 description

Swashbuckler

Your author is probably the only person still alive who attended the Senate hearing of Howard Hughes. There is probably a lot to this story yet to emerge.

Show Biz Image: Hepburn, Rogers, Kelly

Hollywood presented a cartoon of the upper class during the Depression. World War II was soon to sober us up.

Hollywood presented a cartoon of the upper class during the Depression. World War II was soon to sober us up.

Evo-Devo

The Franklin Institute has been making awards for scientific achievement for 188 years, long before the Nobel Prize was invented. The seats are all reserved before the meeting notices are even mailed.

The Franklin Institute has been making awards for scientific achievement for 188 years, long before the Nobel Prize was invented. The seats are all reserved before the meeting notices are even mailed.