Related Topics

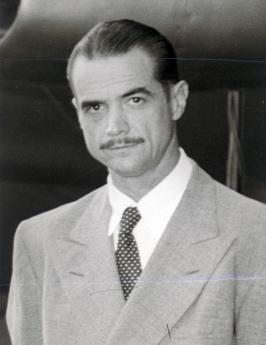

Howard Hughes, Swashbuckler

New topic 2019-01-09 20:07:02 description

World War I's Only True Winner

America’s military involvement in World War I was not a given. Only in April 1917, after three years of warfare in Europe and renewed U-boat attacks on American shipping, did President Woodrow Wilson ask Congress to declare war on Germany. At the time, the U.S. Army was sorely lacking— 200,000 lax regulars and 400,000 National Guard troops more suited to quelling labor strife than engaging in deadly trench warfare. Eventually, three million men would be drafted into a total a force of almost four million, many of them first-generation immigrants, including Germans still speaking their native tongue.

By the time of America’s decision to enter the war, the collapse of czarist Russia in the east had enabled Germany to augment its depleted western ranks with an additional million troops. Germany hadn’t achieved its visions of empire, but a decisive blow before the Americans could arrive in force might allow it to garner a favorable armistice and ensure its standing among the major powers.

SONS OF FREEDOM

By Geoffrey Wawro

Basic, 596 pages, $35

NEVER IN FINER COMPANY

By Edward G. Lengel

Da Capo, 358 pages, $28

In “Sons of Freedom: The Forgotten American Soldiers Who Defeated Germany in World War I,†Geoffrey Wawro, a professor of history and director of the Military History Center at the University of North Texas, states forcefully: “Had the Americans not entered the war and deployed two million troops to France, the Allies would almost certainly have lost†and “the global balance of power would have tipped heavily in Berlin’s favor.†He admits that the strength of his conclusion surprised even him and that he came to it only after extensive research in the national archives of the belligerents.

In the spring of 1918, Gen. Erich Ludendorff orchestrated a series of German offensives to divide and defeat the worn-out British and French armies. Midway through these offensives, German troops got a taste of a new fury. The American 1st Infantry Division, soon the storied “Big Red One,†attacked at Cantigny in northern France. “It was,†Mr. Wawro notes, “the war’s first American attack delivered with courage and precision, and it was the only Allied offensive operation at a time when the British and French were barely holding on.â€

More came quickly. As Ludendorff aimed for Paris in what became the Second Battle of the Marne, Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, deployed the newly arrived U.S. 2nd and 3rd Divisions to stop the German assault at Château-Thierry, a town on the Marne River, and a nearby forest called Belleau Wood. The attackers were stunned by the ferocity of the American resistance. “Without the Americans,†many German officers insisted, “we would have been in Paris by July.â€

Ludendorff accelerated the timing of his final offensive—“the Peace Offensiveâ€â€”in hopes that it would encourage an armistice before more Americans entered the lines. But once opened, there was no turning off the American spigot. By the late summer of 1918, 1.2 million American troops were in France, with 250,000 more arriving every month.

Their learning curve was steep. Training was frequently cut short, and experience had to be gained in place. Across a barbed-wire-laced maze of trenches, baptisms under fire were abrupt and deadly, coming from the new weaponry of poison gas, machine guns, airplanes and heavy artillery. Artillery, including a battery commanded by Capt. Harry Truman, rarely seemed to be in the right place. Tanks commanded by Lt. Col. George Patton suffered mechanical breakdowns or tumbled into ditches.

But out of this crucible came competence that proved decisive in what came to be called the Hundred Days. With Ludendorff’s offensives thwarted, Pershing consolidated his divisions into an all-American sector near Verdun on the eastern end of the Allied line. While questioning some of Pershing’s tactical skills, Mr. Wawro nonetheless credits his relentless commitment to keeping the U.S. Army together under one command rather than parceling its units out as replacements to the British and French. Ultimately, American success in this sector would seal the fate of the German army.

Pershing and his “doughboys†beat back a threatening bulge in the German lines at Saint-Mihiel and then turned north, intent on cutting key rail lines that fed and supplied German troops farther west. The American line of attack pointed straight toward dense German defenses between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River.

Once the Meuse-Argonne offensive got underway on Sept. 26, 1918, it was all or nothing. There were no stopping places. Lamenting the bristling defenses arrayed against them, one doughboy swore: “Every goddam German there who didn’t have a machine gun had a cannon.†Throughout his narrative—both a stirring story and a careful work of military history—Mr. Wawro is adept at explaining tactics and keeping generals and units on both sides straight.

Newsletter Sign-up

Among the units attacking headlong into the Argonne Forest was the 77th “Metropolitan†Division. Few stories are as well known as that of the 600 men from the division who found themselves, in the first week of October, cut off from their lines. They became “the lost battalion.†In retelling their story in “Never in Finer Company: The Men of the Great War’s Lost Battalion,†Edward G. Lengel, whose books include “To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918†(2008), focuses on the ranking officer, Maj. Charles Whittlesey, and his steady second in command, Capt. George McMurtry.

Whittlesey was a scholarly New York attorney more at home peering through thick eyeglasses at law books than at enemy trenches. McMurtry was a stockbroker whose solid build attested to the prep-school boxing champion he had been. Both men had volunteered for a reserve officer training program before America entered the war.

Recruited from the sidewalks of New York, the 77th Division was “almost ridiculous†in its diversity, Mr. Lengel writes. There were “Jews (one out of every four men, according to a census), Chinese, Poles, Italians, Irish, Greeks, Russians, Germans, and Anglo-Saxons.†The only New Yorkers missing, he notes, were African-Americans, barred by the Army’s segregation policies. (Many New York blacks did, however, serve in the segregated 93rd Division’s regiment of “Harlem Hellfighters.â€)

Maj. Gen. Robert Alexander, in command of the 77th Division barely a month, was explicit in his orders: Push forward; ignore your flanks; focus on the objective. Whittlesey and his doughboys did just that and became not so much “lost†as outflanked and surrounded by German troops. Entrapped in the Argonne’s tangle of deep ravines, they faced a nightmare of pounding artillery bombardments (some from friendly fire), rattling machine guns, scarce water, little sleep, and no food. Men died outright; others succumbed to wounds after excruciating days. When relief finally arrived a week later, Whittlesey and McMurtry counted only 194 men, of the original 600, who had escaped the woods with them.

Shell-shocked by the loss of so many under his command, Whittlesey committed suicide three years later. McMurtry lived to the age of 82, dying in 1958, but he seemed to carry Whittlesey’s burden as well as his own. “As long as you and I live,†McMurtry told gatherings of Lost Battalion survivors, “we will never be in finer company.â€

That could be said of all who served in the Meuse-Argonne during that bloody autumn. “The three weeks after October 10,†Mr. Wawro writes in “Sons of Freedom,†“were the grittiest of the war, the Germans throwing in the last of their first-class divisions . . . and the three American corps measuring their daily advances in yards.†The Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery holds the largest number of American dead of any military cemetery in Europe.

Then, rather suddenly, it was over. British and French attacks all along the Allied lines had driven the Germans back, but it was the American thrust on the Meuse-Argonne front that threatened to surround a goodly portion of the German army. Faced with a similar collapse on the Austro-Hungarian front and widespread unrest at home, Germany once again looked for an armistice. Britain and France accepted Germany’s plea because they sensed that time was running out on their side, too.

America’s European allies “knew America had saved them,†Mr. Wawro writes, “but they deplored the political cost and its vast ramifications.†The Yanks that the British and French desperately needed in 1917 had crossed the ocean in force and become the trans-Atlantic power to be reckoned with in 1918 and beyond. “The world,†Mr. Wawro concludes, “would never be the same again.â€

—Mr. Borneman’s “Brothers Down Pearl Harbor and the Fate of the Many Brothers Aboard the USS Arizona†will be published in May.

Originally published: Wednesday, January 09, 2019; most-recently modified: Wednesday, June 05, 2019