3 Volumes

Philadelphia Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began about the time America declared Independence. The young nation faced a clean slate and boundless opportunities.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Gilded Age

They made their fortunes in the West, but spent them in Philadelphia. Until they settled in the West, themselves.

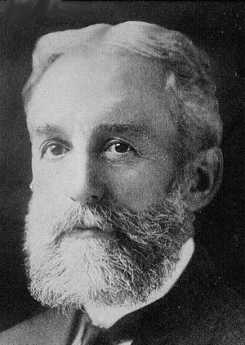

Curtis

To Cy Curtis, magazines were just vehicles for advertisers. In fact, his mags taught former farmers how to manage urban life, more or less accidentally creating a focus for American books, authors, politics and literature. The fall of his empire teaches the lesson that antitrust laws against vertical integration are probably unnecessary.

Curtis: The Business Plan

|

| Cyrus Curtis |

Years ago, Cyrus Curtis maintained you could tell who read a magazine by simply looking at the ads. In his view, a magazine was a means for advertisers to reach selected customers; the text was just baited. Hearing this offensive view, I immediately picked up a high-brow glossy magazine, one with rather advanced literary pretensions, and flipped through its ads. They consisted entirely of ads for cigarettes and liquor. In a flash, I got entirely new insight about that magazine, and maybe an important truth about high-brow readers.

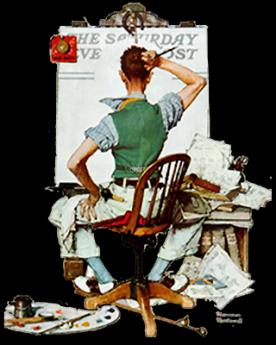

Well before World War I, Cy Curtis had grasped the idea that the real revenue of magazines could be advertising revenue, and the secret of rich revenue was getting potential customers to read the thing. Giving it away free wasn't good enough, you even had to be willing to bribe people to read. The form of bribing people was to provide high-quality reading material at less than cost. Curtis was a businessman, not an editor. His business plan was to hire good editors and then leave them alone. If circulation numbers increased, that must be a good editor.

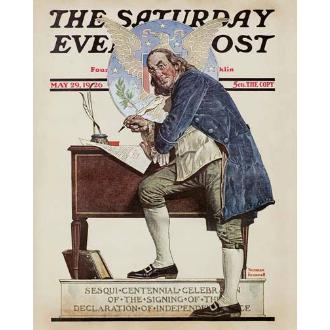

For many years, the Post by that definition had good editors. Its circulation rose into the millions, followed by advertising revenue in the hundreds of millions. It happens that the editorial mix which produced this result was a combination of first-rate fiction and interesting articles built around the theme of glamorous home improvements (for women) or how to make your way as a small business entrepreneur (for men readers). The Post was a how-to manual for a population moving off the farm, into the towns. If it were still published today, it would be called the Bible of the "red" states, the core of the Republican party. That's what the picture of Ben Franklin on the masthead was meant to signify, not the rather tenuous connection with Franklin printing press.

|

| Ben Franklin on the Cover |

In retrospect after the glory days of the Post were over, there developed a general agreement that what killed the magazine was television. Free television; with huge expenditures on entertainment programs. Television is a way of funneling gobs of money from national commodity advertising into the pockets of the entertainment industry. In effect, show biz robbed publishing biz and Hollywood robbed the libraries and bookstores. New York and Hollywood robbed Philadelphia and Boston. And the brokers for this transaction were the advertising agencies of Madison Avenue.

That how it may seem in retrospect, but at the time it was more personal. It seemed as though Life and Look beat the Post, when in fact they just lasted a couple years longer. It looked as though single-subject magazines beat out general-topic magazines, but notice that PC Magazine rose to a thousand fat pages an issue in the 1980s and then fell to its present fifty skinny ones.

A particular source of bitterness lay in the fact that during the last ten years of its life, the circulation of the Saturday Evening Post actually doubled, far higher than it had ever been. If circulation was what advertisers wanted, where were they? The editors of the Post felt they had been betrayed by a conspiracy of a handful of two-martini advertising agents in New York, and it must be admitted there was a wide cultural divide between Sunset Boulevard and Walnut Street, between Greenwich Village and Bucks County. Between the flower children and the gardening clubs. And even, we have to say it, between the Ds and the Rs.

It took almost eighty years for it to happen, but Cyrus Curtis was eventually hoisted on his own petard. No amount of circulation, no level of editorial excellence, was going to rescue a magazine when its advertisers got steered to serving a different sort of free lunch in the barroom. The success of a magazine did not depend on the management of the magazine, it depended on the tribal convictions of the advertisers. The producers of operas, symphonies, and professional sports need to be wary of the same trap; even with a full house, the performing arts cannot meet their expenses from ticket sales, alone. In the cruel arithmetic of economic survival, it may not completely matter how good the artistic performance is.

Curtis and the Book Trade

|

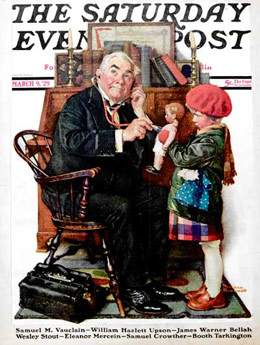

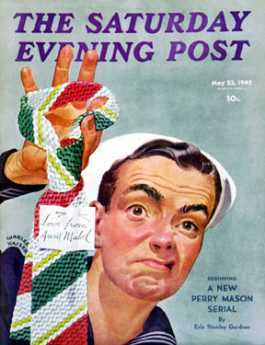

| The Saturday Evening Post |

Few seem to have commented much on the connection between the death of the Saturday Evening Post and the subsequent decline of the book publishing business. The Curtis Publishing Company published books, of course, but that's only a small part of the matter. The general-interest magazines, the Post in particular, were places where authors built their reputations, often long before they had started writing their books.

The Post would run eight or more long articles each week, and at least two serials. From the parochial point of view of the weekly magazine, a serial was a teaser, getting the reader interested and eagerly looking forward to the next installment and the next after that. Another way of looking at it, however, was as one very long piece, larger than a magazine article, but not as big as a book. Sometimes, an eight- or ten piece serial was longer than a small book. This was a wonderful incubator for new authors, and for advance publicity for established authors planning a forthcoming book on the same topic. The big magazines paid pretty well for articles, so writing for the Post was a good way for an author to support himself during the long famines between big books.

|

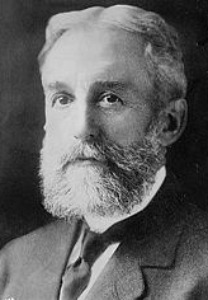

| Cyrus H.K. Curtis |

The general interest magazine wasn't designed for the purpose of supporting the book publishing industry, but it definitely evolved that way. With the disappearance, of not just the Post but of all general interest weekly magazines, the dynamics are now a lot clearer. A new author of a book today has a terribly difficult time establishing a name and a following. The striking thing is that the advent of the home computer has caused an enormous outpouring of new, excellent, manuscripts which cannot find a publisher because it's so hard to get a first-book author established. In 2006, over two hundred thousand new books were published, and many obscure titles were actually quite good books. With shorter print runs as the market gets splintered, the cost per book has skyrocket Dutch and German companies, plus a vast number of small self-publishing enterprises. Much of this sad phenomenon has been blamed on TV, or the Internet, or the school systems. You just can't get people to read and write, these days it is said, but don't believe it. There are dozens of books languishing today that would have competed very effectively with Hemingway and Dreiser and Aldous Huxley. What's much harder is to get a readership assembled for a new author without spending a king's ransom on hype and publicity; if you are going to invest that much money, the business imperative is to invest it on trash, because trash really will sell if you hype it enough. High-class literature is supposed to sell itself.

Every new author is shocked to discover that it takes a full year for his manuscript to wend its way into the bookstores if you can find a bookstore. It doesn't take that long to edit and design a book. It takes that much time to arrange the publicity, and pace its appearance for the book fairs, for the Christmas season, and the reviewers. You can give a free book to a reviewer who truly means to read it, but he may not read it for months. Most book distributors and sellers will not accept a book until they see what the reviewers say. It takes a long time, it costs a lot of money, and it often is unsuccessful. It's all pretty pathetic, compared with sending a chapter to the Saturday Evening Post, getting paid to put your author in front of ten million readers.

Working Girls Get the Faints

|

| Curtis Building |

Curtis Publishing Company once covered a full city block of Philadelphia, from Sixth to Seventh Streets, Walnut to Chestnut. The northern half of this complex was the Public Ledger Building, once housing a failed diversification move into newspaper publishing and later rented out as commercial office space after the newspaper died. On the top floor of the Ledger Building was the Down Town Club, quite a palatial meeting place for the whole publishing industry which stretched for blocks around. Both Curtis-owned buildings have the same architectural design and together make a massive looming presence next to Independence Hall on one street and Washington Square on the other. To build from Walnut to Chestnut means shutting off Sansom Street in the middle, and that permits the jewelry trade to nestle in a cul de sac on the West side of the publishing complex.

So Curtis was once a little city within a city, and most of the rest of the town only saw its facade and the crowds of people coming and going through the entrances. To a neighborhood doctor on an emergency call, however, it was almost exclusively inhabited by young women. Kitty Foyles, you might say. I certainly formed that impression after having a medical office two blocks away, getting occasional calls.

|

| Christopher Morely |

So far as I can remember, Curtis had only one medical problem, repeated over and over. An anguished call would come that someone at Curtis was unconscious, come immediately, take the elevator to the third or fourth or fifth floor. At the elevator, the doctor would be met by a somewhat older woman, obviously the den mother of the working girls. Into the ladies room, we would go, where a young woman was usually sitting on a couch looking sheepish, although occasionally she was still passed out. The key finding was a very slow pulse. She had fainted, she was better, and now what. It was Curtis policy to send the fainters home after the faint, and I never could see any particular objection to that.

For me, there were never any men to be seen, at Curtis. Surely there must have been dozens of writers and editors and advertising people, but somehow they would vanish when one of these fainting things happened. Curtis was nothing but women when I was there, mostly watching me like a beach full of seagulls, watching a fisherman.

Curtis: Textbook Case for Business School

The Sherman antitrust law often stands with the Ten Commandments and the Gettysburg Address as holy writ. However, in the view of other people, it is a hopeless muddle. One has to pity the poor students in Law School and Business School, who have no small problem deciding what they think of antitrust, and also the unspoken problem of guessing the bias of the person who is going to grade the final examination. The death throes of the Curtis Publishing Company give a good example of what's involved in Vertical Integration, the current hot button of antitrust disputes. Let's explain. Horizontal integration takes place when a company merges with its direct competitor in the same line of work; we're not talking about that. Vertical integration, our present topic, describes the situation where a company merges with one of its suppliers or one of its customers. Should the government permit such a thing to happen? Competition appears to be lessened by Vertical Integration because seemingly no one can gain a competitive foothold against an entrenched giant that owns everything it needs. Much clamor arises that it should be forbidden. Let's look at what happened to Curtis, which was as self-sufficient as it is possible for a magazine publisher to get.

The Saturday Evening Post established itself as the dominant general-interest magazine long before other major competitors in the late Twentieth Century. Generating huge revenues, the Curtis Publishing Company bought its own printing plant, and eventually vast forests of trees to feed the paper company it also owned. For them to do so might be justified as assuring a dependable, steady supply of materials for their own needs, but it is also true that tax laws create an opportunity to bury profits within a now more broadly defined business. Revenues sunk in a paper mill are a business expense; revenues transformed into cash translate into more taxes and generate stockholder demands to be paid dividends. Competitors howl; how can we compete with a company that can control the cost of its supplies? Unfair. The Great Depression of the 1930s, however, exposed the advantage as a disadvantage. Paper mills were going bankrupt and had to lower their prices severely in order to make any sales at all. Curtis, on the other hand, had to absorb the losses of its paper companies as well as losses in its main magazine business, essentially paying full price for paper when the competitors were getting a distressed discount. The lessons to be drawn from this textbook case can be different for law students and business students. For business students, the moral is that vertical integration is a bonus in good times, but a risky thing in less prosperous times. For law students, the question would more likely be whether it is in the public interest to let businesses alternate between injuring their competitors, and then themselves, by taking such risks. In a much later case, State Oil v. Kahn, the U.S. Supreme Court seemed to conclude that vertical integration was so inherently self-defeating it was unnecessary to make it illegal. Curtis: Those 1905 Delivery Trucks

The Curtis Publishing Company was symbolic of Philadelphia in a lot of ways, like the silhouette of Ben Franklin on its masthead, the deliberately old-fashioned type font of the Post's title above the Norman Rockwell paintings on the cover. Since Curtis stopped publishing magazines, the sturdy old buildings have been converted to modern office space. If you stroll around today, you get a completely misleading impression of the headquarters. To some extent, the present lavish interiors are a response to the Tax Act of 1975, which specifies that the cost of a rehabilitation project must exceed the previous value of the building. And to some extent, the present luxury reflects the deluded ideas of architects and dreamers about the proper lifestyle for captains of industry. To view this rehab, you might suppose:

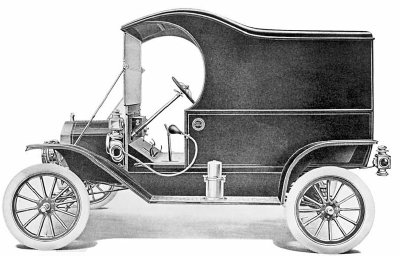

If you came to visit Curtis in Philadelphia, you would be invited to have lunch in the Down Town Club, and then enter the office complex proper through ornate bronze doors, going down spectacular gleaming interiors past a splendid indoor fountain at the foot of a magnificent huge marble staircase leading who knows where. There would be opulence on all sides, punctuated by an enormous glass mosaic constructed by Louis Comfort Tiffany on a design by Maxfield Parrish. Curtis must have had a wow first floor, designed to impress visitors, and every bit as successfully impressive as anything in New York or Washington DC. In case you didn't get the point, this looming structure did its looming right across the street from Independence Hall. That's the impression you would get today, without a uniformed guide to explain things to you. But as a matter of fact, those high, high ceilings were meant to enclose printing presses, which are notoriously noisy, smelly, and greasy. This was a place of business, a manufacturing plant, not a tourist attraction. The real symbolism of no-nonsense Philadelphia manufacturing could be seen, every day on the streets. It was those funny old delivery trucks. Everyone in Philadelphia in the morning was familiar with these relics, great lumbering elephants traveling at about five miles an hour or less making grinding noises, slowing up traffic, looking terribly old fashioned. As a matter of fact, they were built in 1905 and were powered by electric batteries. Indestructible, requiring neither maintenance nor fuel except for recharging the batteries overnight. They did their job of transporting paper and magazine product back and forth from Washington Square to the printing plant at Sharon Hill, and there was absolutely no economic justification for replacing them with something more expensive. Their cast iron construction was such that there would probably never be an economic reason to replace them; funny looking, maybe, but they were money in the bank. Philadelphia loved them like a dotty old maiden aunt.

But just imagine the impression they gave the two-martini crowd when they came down from New York for a job interview or for business negotiations. The trucks symbolized the fuddy-duddy city with its fuddy-duddy magazine. Imagine working for a place that would tolerate those things, and what's even more unimaginable, the local yokels actually defended them. The word "cool" was invented to represent everything that these old trucks were not; didn't want to be. Just seeing one of them was enough to make you take your hard-leather heels back to Madison, and Lex, and The Village. Even after first impressions faded, the true symbolism of those trucks was troublesome to glitterati. The impression the trucks gave to visiting readers of the Post was quite in keeping with the magazine's decades-long message of hard work, frugality, and no-nonsense pruning of expenses. A chance visitor to Independence Hall could plink the Liberty Bell and then wander over to that Taj Mahal on the West side of Sixth Street, quite likely thunderstruck by the interior. Out of town readers would, of course, have been even more dumbstruck to see the mansion that the Curtis family lived in on Rittenhouse Square and elsewhere, but all that was at a discreet distance. And then, one of those nice old trucks would come lumbering along. Now that's the spirit. That's the message of crafty old Ben Franklin. Who cares what people think about the outward show, especially those, ugh, people from New York. Rise and Fall of Books

John C. Van Horne, the current director of the Library Company of Philadelphia recently told the Right Angle Club of the history of his institution. It was an interesting description of an important evolution from Ben Franklin's original idea to what it is today: a non-circulating research library, with a focus on 18th and 19th Century books, particularly those dealing with the founding of the nation, and, African American studies. Some of Mr. Van Horne's most interesting remarks were incidental to a rather offhand analysis of the rise and decline of books. One suspects he has been thinking about this topic so long it creeps into almost anything else he says.

Franklin devised the idea of having fifty of his friends subscribe a pool of money to purchase, originally, 375 books which they shared. The members were mainly artisans and the books were heavily concentrated in practical matters of use in their trades. In time, annual contributions were solicited for new acquisitions, and the public was invited to share the library. At present, a membership costs $200, and annual dues are $50. Somewhere along the line, someone took the famous cartoon of the snake cut into 13 pieces, and applied its motto to membership solicitations: "Join or die." For sixteen years, the Library Company was the Library of Congress, but it was also a museum of odd artifacts donated by the townsfolk, as well as the workplace where Franklin conducted his famous experiments on electricity. Moving between the second floor of Carpenters Hall to its own building on 5th Street, it next made an unfortunate move to South Broad Street after James and Phoebe Rush donated the Ridgeway Library. That building was particularly handsome, but bad guesses as to the future demographics of South Philadelphia left it stranded until modified operations finally moved to the present location on Locust Street west of 13th. More recently, it also acquired the old Cassatt mansion next door, using it to house visiting scholars in residence, and sharing some activities with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on its eastern side.

The notion of the Library Company as the oldest library in the country tends to generate reflections about the rise of libraries, of books, and publications in general. Prior to 1800, only a scattering of pamphlets and books were printed in America or in the world for that matter, compared with the huge flowering of books, libraries, and authorship which were to characterize the 19th Century. Education and literacy spread, encouraged by the Industrial Revolution applying its transformative power to the industry of publishing. All of this lasted about a hundred fifty years, and we now can see publishing in severe decline with an uncertain future. It's true that millions of books are still printed, and hundreds of thousands of authors are making some sort of living. But profitability is sharply declining, and competitive media are flourishing. Books will persist for quite a while, but it is obvious that unknowable upheavals are going to come. The future role of libraries is particularly questionable. Rather than speculate about the internet and electronic media, it may be helpful to regard industries as having a normal life span which cannot be indefinitely extended by rescue efforts. No purpose would be served by hastening the decline of publishing, but things may work out better if we ask ourselves how we should best predict and accommodate its impending creative transformation. www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1470.htm Philadelphia: A 1925 Viewpoint

In 1925, George Barton published a charming series of reflections about his own wanderings around downtown Philadelphia, entitled "Little Journeys Around Old Philadelphia". Rittenhouse Square Area

The Rittenhouse Square "area" has far outgrown the square itself, and the term when used by locals usually refers to the whole area of central Philadelphia West of Broad Street to the Schuylkill, bounded roughly by Chestnut Street on the North, and Pine Street on the South. Rittenhouse Square Park is in the center of this primarily residential area and is now mostly ringed by apartment buildings. Rittenhouse Park was once enclosed by a high cast-iron fence with sharp-pointed palings and gates that could be locked at night, just like so many London Squares. The fence disappeared around 1900. Around 1840 the first house was built on the square, and then a fifty-year building boom (reflecting the burgeoning prosperity of the city) filled the fashionable area out to the limits defined by the Schuylkill bridges at South Street and Walnut or Chestnut Streets. Because of the advent of central heating and inexpensive window glass manufacture, the low ceilings and small windows to the East of Broad Street (promoted by the need for fireplace heat, plus laws taxing both windows and white paint) were replaced by tall ceilings and big windows without mullions. These townhouses were big, often with twenty or more rooms, and the occasional narrow streets filled with small houses were for servants, however, gentrified they may have recently become. The center of fashion shifted over the years, and right now probably Delancey Street is the pinnacle, although it is patchy and arguable. After the 1929 crash (of the stock market), many fashionable Families had to abandon the unmaintainable big house and move into the little servant house in the neighboring alley in order to remain in the fashionable area. The Big houses with its big taxes then became several apartments or a storefront with apartments above. Or it just deteriorated and then was torn down, unless some economic up swelling happened to rescue it again. The fact is that the number of big houses in the area exceeds the number of wealthy people who want to live in them, and the fashionable area has thus had to contract, but it has not disappeared, either.

Rather than swamp this blog with a tedious recital of the previous occupants of so many show houses, let it suffices to say that the families which once had the most Notable Houses around and near Rittenhouse Square were Roberts, Weightman, Frazier, Gibbs, Harrison, Stotesbury, Cassatt, Jayne, Harding, Janney, Gazzam, Scott, Dobbins, Bullitt, Baugh -- and, of course, many others too. Within this district, churches abound at the Northwest corner. Clubs are strung along the Eastern border, between the residences and the financial district along Broad Street. And the Southern border is where the doctors used to be. I had an office once at 19th and the Square, but the main concentration of doctors was on Spruce Street. If you have seen Harley Street in London, you will recognize the pattern. Originally, the doctor had his office on the ground floor and lived upstairs. The zoning regulations in both London and Philadelphia permitted professional use of the first floor only if the professional lived in the house. So, when the advent of automobiles induced most doctors to live in the suburbs, the office continued on the first floor of these houses, and the doctor's nurse lived upstairs, to satisfy the requirement of the zoning law. But that was just a transient phase; the advent of health insurance during World War II induced a more hospital-centered medical practice, and Spruce Street soon lost its medical flavor as doctors concentrated their offices around hospitals and their ample parking lots.

As traffic heading for the South Street bridge or the Walnut-Chestnut-Market bridges defines the limits of the district, the Rittenhouse Area has more or less contracted to the four blocks of East-West streets which terminate at the river, creating a more quiet and peaceful cul-de-sac. Some idea of the former grandeur of the area can be gained by looking at the former Van Rensselaer home at 18th and Walnut, which had a brief fling as a private club before it became a gift shop. Or the Wetherill Mansion further South on 18th Street which now houses the art alliance. Or the grey stone house a couple of doors to the West of it which was where Governor Earle lived and was the last single-family house on the square. One of the houses on DeLancey Street was featured in the movie "Trading Places" as Hollywood's idea of real opulence, and a great many other houses tell a famous story. The Rosenbach Museum is at Spruce Street, very well worth a visit, particularly on Bloomsday. And the Thaw House at 1710 Spruce tells a particularly lurid tale of the Gilded Age. Frederick Mason Jones,Jr. 1919-2009

Classical music, however else it may be defined, strongly implies music played by an orchestra, or at least a group of musicians. It thus should be no surprise that the members of a famous orchestra bond together for most of their lifetimes in a sense far beyond the ordinary meaning of teamwork. If you are good, really, really good, you will come to the orchestra as a boy, devote every hour of every day to the orchestra, and step down only as a famous old man when you sense that reaction times have slowed. You sit together, travel together, rehearse together, and talk a language of detail which no one else can fully comprehend. Mistakes that one of you made forty years ago in performance, are still joked about because your colleagues know you still feel the pain of it, just as they share their own infrequent but no less fully remembered, moments of failure, largely unnoticed by the audience. When one of your colleagues dies, you turn out by the hundreds for the funeral. And when the hymns are sung, the organist is ignored, struggling to keep up with the people who really know music. Mason Jones attended the Curtis Institute, itself a collection of prodigies, and was hired by Ormandy after a single audition; a year later he took the position of a first horn and kept it until he finally sensed he was passing his prime and laid it down. He was featured in the many recordings which defined the orchestra, and the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet. He sometimes recorded as a soloist, but he thought of himself as an orchestral horn player, teaching orchestral horn at the Curtis to many generations of aspirants. He even conducted a little, usually in small groups. His comment on that was that it doesn't take much to be a conductor. "Just ask any orchestra player." At his funeral, it was related that the second horn once had two solo passages repeated within a larger piece, but when its time came there was silence. The second time around, it was played faultlessly. Afterward, Mason was asked what happened. "Fell asleep," he answered. And the second time? "I just played it for him."

Mason's funeral was held at St. Peter's in the Great Valley, illustrating that strange combination of artistic prodigies with modest beginnings, and the highest of high society, who mix together to create a great orchestra. A very well-groomed lady was heard to remark that this was where she had her coming-out party. St. Peters was founded as an Anglican mission church in 1700 in the Welsh Barony, built a log cabin church in 1728, replaced it with a little white jewel of a church in 1856, and added new buildings in the past few years to accommodate the population growth in the valley. The church has abundant well-tended land, sited on a hilltop surrounded by high hills, quite suitable for a college or private school campus. The homes in the area are a step beyond splendid, hidden in the wooded countryside. Unless you know precisely where to go, the tangle of country roads will defeat you. But the arterial of U.S. 202 is only a few miles away, and Philadelphia's silicon valley nestles beside the highway, inevitably closing in on the countryside. There will be horses and kennels and fox hunts in the region for another decade perhaps, but the new world is moving in on the old one, from all directions. Curtis Center

Tell your taxi driver that the Curtis Center is between 16th and 18th Streets on Locust, and not at 6th and Walnut. The big building next to Independence Hall is the former site of the Curtis Publishing Company, where all the money was made with the Saturday Evening Post. The Curtis Center is the present home of the Curtis Institute of Music, founded in 1924 by Mary Louise Curtis Bok with the advice of Leonard Stokowski, and with the determination to make it the best school of music in the world. The big competition, then as now, was the Juilliard School in New York, which is considerably larger. The New York competitor has the advantage that it sits on top of the Metropolitan Opera House within Lincoln Center. The Curtis, however, has a trump card; no student pays tuition, and the school tries to provide assistance for other costs of the students. Because of Juilliard's location closer to many performing arts centers, it can draw on a larger pool of commuting students and faculty, and is probably considered the top choice by the talented pool of applicants. But Curtis is gaining; only two of the accepted applicants from last year's class of 48 students chose to go to another school.

In this fiercely competitive game, the school which is coming from the rearmost recently is the Colburn School of Music at UCLA. Not only does Colburn have Mr. Colburn's declaration in his will that he wanted to make it the "Curtis of the West", it is also heavily supported by Universal Studios, and has the additional advantage that Oriental students are flocking to the United States for musical training, and there are, of course, a lot of them. The previous director of Curtis is invited to China every year at the expense of the Chinese government, just to listen to what Chinese students sound like. It's sort of like inviting the college admission officer to your home to listen to your children describe their extra-curricular talents, but that's the way things are in the highly, highly competitive world of music. Running schools of music are no exception to that; don't forget music schools named for Peabody and George Eastman, and Boston's New England Conservatory of Music. Definitely a hobby for a person of means.

Like Gerry Lendfest, the Chairman of the Curtis Board. On his own, he bought the old Locust Club property and the two neighboring houses, and gave it to the Curtis if they would pledge to raise $35 million to fit it out. That's been done, and there is now a big hole in the ground across Locust Street from the Wannamaker Chapel of St. Mark's Church. The plan is to construct a five-story building on Locust Street in conformity to the wishes of the Planning Commission, but the building will rise to the level of a 9-story building on Latimer Street. Somewhere tucked in there will be an orchestra rehearsal center, a library, and many instrumental practice halls. Plus a dining room for everybody in the school, and about 85 dormitory rooms for students. Mr. Lendfest is obviously a keen competitor in the music school game. The school has 85 faculty members for 165 students, half of whom come from overseas, and are male/female 50%. An occasional student is seven years old, in the style of Mozart, and every single student knows that just about every other student is just about as talented as he/she is. The test of it all is the careers of the students, who quite naturally fill up many of the places in the Philadelphia Orchestra. Famous graduates are Leonard Bernstein, Samuel Barker, Juan Carlo Menotti, Ephraim Zimbalist, and many others. There's little doubt that the original idea was to bring Central European music to America, but two world wars and the relentless pressures of outstandingly talented students have broadened the horizons to a modern vision of the future of music. One particularly significant development is the laying of fiber-optic cable from Temple to the Kimmel Center, and a planned branching to the Curtis Center. That's the new and improved Internet II, which will make virtual conducting of virtual orchestras all over the world a possibility. Keep tuned. Pipe Organs, and SimilarThe Franklin Inn Club was pleased to hear a talk about pipe organs the other evening, by one of its members, Wesley Parrott. Wesley has degrees in the subject from the Curtis Institute and Eastman and was accompanied by Riyehee Hong, who has a Ph.D. degree on the subject from the Moore College. Wesley is now the organist at St. Mary's Church on Cathedral Avenue.

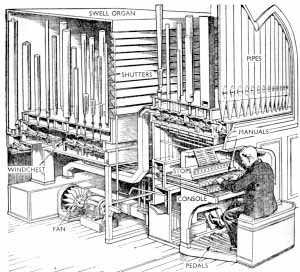

The flute is just about the oldest musical instrument if you regard a pipe organ to be essentially a large collection of flutes with a single mechanical air blower, controlled by a console. Bagpipes almost fit that description, too, except a bagpiper first fills the bag with air he blows in by himself, and fingers the holes in the pipes for individual notes, whereas the pipe organist has mechanical assistance to supply the air and control the pipes. It seems to have been Emperor Charlemagne who decreed the pipe organ would contribute the main music of churches, and to fit this role, pipe organs in France and Italy evolved in the direction of elaborating the overtones and color characteristics of the organ as sort of a soloist in a church. Organs from this distant era are still playable but seem tiny in comparison with later examples. German music, in general, has always emphasized melody over elaborate overtones, and German organs evolved in the direction of distinctive notes in counterpoint. That has been true for centuries, but it was the missionary surgeon Albert Schweitzer who most recently made great steps away from French influences back toward melody and counterpoint, both in musical composition and in mechanical modifications of the instrument to suit that baroque goal. The mechanical underpinning of this distinction lies in the immediacy of response and shortening of tone decay, making the notes crisper. The older French version tends to smear the notes together, like a young person who talks too fast. The whole French language shares that characteristic of slurring words together, and speakers thus seem to be talking a little too fast to be understood. The German language is more staccato, with distinct separate words. In general, pipe organs tend to be either of the French or the German style, but there is a great deal of individual variation, resulting in subtle distinctions lost on most audiences. The design and construction of organs remained essentially unchanged from 1390 when l' Orge de Valere" was published by Guy Bovet, until 1876, when the great modern innovation of the electric organ was displayed in Philadelphia.

In fact, two modern changes were heavily American-influenced. The most important change in the mechanics after five hundred years was introduced at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, by Hilborne L. Roosevelt, a cousin of Teddy, and son of S. Weir Roosevelt. The organ on display was the main organ of the main exposition building and created a sensation. Although he was only 37 years old when he died ten years later, Roosevelt became one of the largest organ manufacturers in America, a friend of Thomas Edison, and was recognized for a number of electrical inventions. Electrical control of the blower and valves greatly expanded the potential for size and complexity of the keyboard console. Up until that time, the keys were pounded with the organist's fists, and organists therefore somewhat resembled blacksmiths, both in musculature and temperament. The application of electricity greatly expanded the complexity and artistic potential of both the German and French styles. Meanwhile, the symphony orchestra was evolving throughout the 19th Century, and now the organ was able to imitate the whole orchestra. This evolution soon developed a mass market in the huge silent movie theaters of the early 20th Century, which in turn generated a pressure to evolve orchestra-like characteristics in the organs installed in the theaters, adding extra pipes and tones to suit that taste, which was exuberant. The advent of sound movies would soon eliminate the need for pipe organs in movie houses, but the instruments were durable and built into the walls. A few of them therefore still remain, largely unused, and probably unusable. The Philadelphia region is unusually rich in pipe organs of various sizes and complexity; students of the subject come here to tour them. Philadelphia's Kimmel Center has a new pipe organ, with two consoles to suit the two main styles of organ music, solo of the Charlemagne sort, and orchestral music. Wesley feels too much emphasis was placed on maximizing the seating capacity of the Kimmel auditorium, causing the organ to be fitted into a narrow tunnel-like enclosure. The resulting sound of the organ has a uni-directional quality which is unrelated to the organ itself; some people criticize the overall result as "assaulting" the audience, but whether for better or worse the Kimmel Center distinctively has a Kimmel sound. The electronic organ, as distinguished from the electric organ, doesn't use pipes, it synthesizes sound. It is far cheaper to manufacture, but is undergoing such rapid change in so many directions nowadays that it resembles the home computer; you have to go to the expense of getting a new one every few years. The electronic organ is clearly catching up with the range and quality of pipe organs but has not yet reached parity except in specialized situations. But its rapid and relatively inexpensive adaptability gives it a great advantage when musical tastes are changing. Modern music places much more emphasis on percussion, and modern society is much less attracted to great big hollow churches. Electronic organs thus change direction faster than multimillion dollar organs of the traditional sort, and slowly, slowly, the quality is catching up, too.

Mite is a long series of picturesque hills of approximately 300 m in height, located in southeastern Poland, near Zamosc. Formerly part of the great aristocratic family fortune Zamoyski, it is a region rich in natural attractions and historical sights and interesting for tourists and anyone who wants to discover the mysterious eastern hills. Some of the region are protected as part of the natural park known as Roztocze National Park. In addition, there are 10 other reserves, and many natural monuments in the area. Most of the park is the forest, cut through the river Pig and numerous steep-sided ravines, loess. If you had to choose just one of many wild animals, it probably would choose the Polish horse, which was again in the park.

Located near the border with Ukraine, the Acari is a typical frontier country, with traces of many cultures here before, everyone in the same turbulent history. In Mites, see the Ukrainian Orthodox churches, Jewish synagogues and the mysterious old cemeteries, and the former residence of the Polish nobility. HOW TO REACH U.S. The main town in the region is < , where you can find rail in Warsaw and Krakow, although trains are not frequent. a significant city in the north of the Mites, and then taking a bus or train to Zamosc Zwierzyniec, Szczebrzeszyn or one of the other cities in the region Mites. Private transport is certainly more convenient. From Warsaw to Lublin, you can get, and Tomaszow Lubelski on the road 17 If you start in Krakow, head east along the E40 to Rzeszow, and then turn on one of the smaller roads leading to different corners of the Mites.

Hi!

Nice site I will return

Curtis myths: Betsy Ross; Ben Franklin publishing legacy.

John Dickinson once lived here.

Downtown club

The mosaic in the lobby.

Curtis family

Curtis Institute of Music

Curtis Clinic at Jefferson

11 Blogs

Curtis: The Business Plan

Curtis and the Book Trade

Working Girls Get the Faints

Curtis: Textbook Case for Business School

Curtis: Those 1905 Delivery Trucks

Rise and Fall of Books

Philadelphia: A 1925 Viewpoint

Rittenhouse Square Area

Frederick Mason Jones,Jr. 1919-2009

Curtis Center

Pipe Organs, and Similar

|

Magazines are sold for less than they cost to print, just as grand opera costs more to produce than the ticket price. Therefore, both survival and failure can have misleading causes.

Magazines are sold for less than they cost to print, just as grand opera costs more to produce than the ticket price. Therefore, both survival and failure can have misleading causes.

The streets around the Curtis Building were populated with huge solid-tire, battery-driven delivery trucks. They were built in 1905, cost almost nothing to run, and crept along at 5 miles an hour. It was impossible not to notice them, and that was the main idea.

The streets around the Curtis Building were populated with huge solid-tire, battery-driven delivery trucks. They were built in 1905, cost almost nothing to run, and crept along at 5 miles an hour. It was impossible not to notice them, and that was the main idea.

This was the heart of uppercrust society during the Gilded Age.

This was the heart of uppercrust society during the Gilded Age.

And how to you? www.google.com