Related Topics

Curtis

To Cy Curtis, magazines were just vehicles for advertisers. In fact, his mags taught former farmers how to manage urban life, more or less accidentally creating a focus for American books, authors, politics and literature. The fall of his empire teaches the lesson that antitrust laws against vertical integration are probably unnecessary.

Curtis: Textbook Case for Business School

|

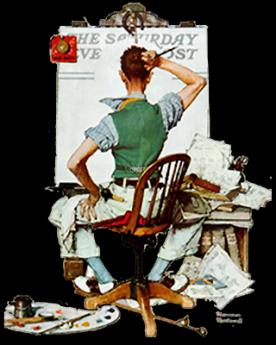

| The Saturday Evening Post |

The Sherman antitrust law often stands with the Ten Commandments and the Gettysburg Address as holy writ. However, in the view of other people, it is a hopeless muddle. One has to pity the poor students in Law School and Business School, who have no small problem deciding what they think of antitrust, and also the unspoken problem of guessing the bias of the person who is going to grade the final examination. The death throes of the Curtis Publishing Company give a good example of what's involved in Vertical Integration, the current hot button of antitrust disputes. Let's explain.

Horizontal integration takes place when a company merges with its direct competitor in the same line of work; we're not talking about that. Vertical integration, our present topic, describes the situation where a company merges with one of its suppliers or one of its customers. Should the government permit such a thing to happen? Competition appears to be lessened by Vertical Integration because seemingly no one can gain a competitive foothold against an entrenched giant that owns everything it needs. Much clamor arises that it should be forbidden. Let's look at what happened to Curtis, which was as self-sufficient as it is possible for a magazine publisher to get.

|

| The Curtis Publishing Company |

The Saturday Evening Post established itself as the dominant general-interest magazine long before other major competitors in the late Twentieth Century. Generating huge revenues, the Curtis Publishing Company bought its own printing plant, and eventually vast forests of trees to feed the paper company it also owned. For them to do so might be justified as assuring a dependable, steady supply of materials for their own needs, but it is also true that tax laws create an opportunity to bury profits within a now more broadly defined business. Revenues sunk in a paper mill are a business expense; revenues transformed into cash translate into more taxes and generate stockholder demands to be paid dividends. Competitors howl; how can we compete with a company that can control the cost of its supplies? Unfair.

The Great Depression of the 1930s, however, exposed the advantage as a disadvantage. Paper mills were going bankrupt and had to lower their prices severely in order to make any sales at all. Curtis, on the other hand, had to absorb the losses of its paper companies as well as losses in its main magazine business, essentially paying full price for paper when the competitors were getting a distressed discount.

The lessons to be drawn from this textbook case can be different for law students and business students. For business students, the moral is that vertical integration is a bonus in good times, but a risky thing in less prosperous times. For law students, the question would more likely be whether it is in the public interest to let businesses alternate between injuring their competitors, and then themselves, by taking such risks. In a much later case, State Oil v. Kahn, the U.S. Supreme Court seemed to conclude that vertical integration was so inherently self-defeating it was unnecessary to make it illegal.

Originally published: Wednesday, June 21, 2006; most-recently modified: Monday, May 20, 2019

| Posted by: Barbi | Apr 23, 2011 4:11 AM |