0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

The Pennamite Wars

The Connecticut farmers believed the King's last word overturned all earlier ones, else why be a king? William Penn's revolutionary idea was that of private property -- the first sale created a new owner, whose new word erased any earlier ones. When you acquire a new continent from aborigines, that's a congenial viewpoint.

The Origin of States Rights, a Rumination

ALMOST alone among the British colonies in America, Pennsylvania's western border was specified in the King's charter of the colony. It was "five degrees longitude west of the point where the eastern boundary crosses the Delaware" [River]; however, its actual location on the ground was not actually marked until 1784. It's a few miles west of the present city of Pittsburgh, located at the forks of the Ohio River, where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers join. However, until 1784 it was not a certainty that this complex was within Pennsylvania instead of Virginia. The origin of Ohio is at the only major water gap in the North-South mountains, and the tributary rivers are fairly large. The three merging rivers thus form a nearly continuous water route along the base of the mountain range, from the Great Lakes south to Pittsburgh, or from the Chesapeake Bay north to Pittsburgh, and then to the Mississippi, going past the best topsoil farming land in the world. The forks of Ohio were the great prize of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, the place where young George Washington himself started the French and Indian War. To include these treasures, it seems vaguely possible that William Penn insisted on having the border of his state safely include the water gap at the beginning of Ohio. Perhaps not, of course, perhaps it was just a sense of tidiness on the part of the ministers of Charles II. The original document stated that the border was a hundred miles east of there, to match where Maryland ended. When the document was returned to Penn by the King's ministers, however, it had the new language.

The existence of this north-south termination of Pennsylvania began to take on a new significance when other states made claims for their land grant to extend to the Pacific Ocean, and the extensions collided with each other. Virginia then developed its territory to include modern Kentucky and West Virginia. That resulted in Virginia's land aspirations veering northward, to include the Ohio Territory west of Pennsylvania's fixed boundary. By the legal standards of the day, Virginia had a fairly good claim to all of the Indian territories, not merely to the west of Pennsylvania, but extending at least to the Great Lakes, perhaps farther. Maryland, Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts had conflicting claims from an infinite extension of their western boundaries. As a consequence, it was impossible to achieve ratification of the Articles of Confederation for five years. The various states involved were fearful of the creation of a combined political entity might result in a court which would be enabled to rule against their individual aspirations. The stakes were high; the land mass involved would be several times as large as England.

The person who finally broke this deadlock might well have been Robert Morris, who was disturbed that this inter-state dissension was injuring his ability to borrow foreign funds for the Revolutionary War. The internal negotiations took place under wartime conditions, and are poorly researched. No doubt some person deserves credit for bringing this wrangle to a close. Virginia had the strongest claim, New York the weakest. New York gave up its claim first, Maryland was the last, and Virginia the most disappointed. Pennsylvania, unable to make a claim, took the position that the land belonged to everyone, and eventually was mollified by getting a small notch of land extending to the Great Lakes at Erie. It must be noticed in passing that final resolution of the land claims came at the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolution. Benjamin Franklin, soon to become President of Pennsylvania, was the negotiator of the treaty which reflected Pennsylvania's position that the land belonged to all of us, right?

Even without these western land claims, Virginia was the largest and richest of the colonies, and rather easily adopted the attitude that Virginia would be the leader of the new United States. From their viewpoint, the preservation of states rights would enhance Virginia's leading the country. More or less immediately, the attitude of small states like Delaware hardened into resistance that this must not happen. Much otherwise inexplicable behavior also begins to make a sort of sense: the perverse behavior of the Lee family in the Continental Congress, the quarrels within George Washington's cabinet, the relocation of the capital and the dreams of the Potomac as the nation's main portal of transportation, the rise of Jefferson's political party, the obstructionist behavior of Patrick Henry, the Virginia domination of the Presidency for decades, and countless less famous episodes of history -- make more sense as residuals of Virginia's early land aspirations, than as defenses of slavery or philosophical convictions that states were somehow superior to nations. These suspicions are difficult to clarify and impossible to prove. The best way to see some substance to them is to imagine yourself in the Virginia House of Burgesses, politically connected and vigorous, able to imagine your descendants all inheriting a county or two of rich land as a remote consequence of a few glamorous deeds by their Cavalier ancestor.

The King's Last and Final Word

|

| King Charles II |

In 1662, King Charles II of England signed a charter, giving a strip of land in America to the inhabitants of Connecticut, and that land to stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. And then, eighteen years later, the same king signed a second charter, giving much the same land to William Penn. As lawyers say, these are the facts. In the many lawsuits, arguments, and wars which followed, no one ever seriously raised the point that King Charles was unaware that he was giving the same land twice, so it must be assumed he knew exactly what he was doing, and did it on purpose. In fact, he did this sort of thing many times, in other cases. The legal disputes which this double-dealing inspired, are therefore entirely concerned with whether the King had a right to do it, and if so, whether that right would normally be recognized (i.e. durable) when we threw off the King and became a republic. The matter was considered by many courts many times, and in every single case, the judgment was in favor of Pennsylvania.

|

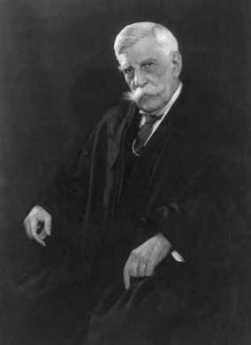

| Oliver Wendel Holmes Jr. |

Consider Connecticut's probable attitude toward all this. The colony was settled by Calvinist dissenters, so-called Roundheads for their surprisingly contemporary haircuts, adherents of General Cromwell, executioners of King Charles I during English Civil War. They gave Old Testament first names to their own children, and had always known they couldn't trust that licentious King. Giving their land away after he had promised it to them was just about what they always expected. When, after seventy years of growing families of fifteen to seventeen children, they discovered that Connecticut soil was merely a pile of pebbles left by the glaciers and covered with a thin layer of topsoil, they became even more convinced they had been cheated in the first place, and the bargain was no bargain. The reverse side of this enduring religious hatred will reappear in a few paragraphs.

The Proprietors of Pennsylvania, by this time no longer pacifist Quakers, but while descendants of William Penn, converted Anglicans and great friends with the King, took the matter calmly. The Connecticut lawyers were saying that if you sell or give away some land, it is no longer yours, so you can't give or sell it a second time. That is the modern view perhaps, but the English-speaking world was changing from a feudal, semi-nomadic, culture into a settled agricultural country where fixed boundaries were only starting to be important. That's where the world was going, but at the time King Charles gave away the land, it was far more important for the King to be able to reward successful underlings, and punish rebellious tribes, as the situation warranted. Ownership of land then seemed a nebulous thing at best, and the King was the best judge of how things should be divvied up.

Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced his book on The Common Law, by warning "The life of the law has not been logic, it has been experience." For life to go on and prosperity to endure, some decision must be made and held to, right or wrong. Stare decisis. That's of course fine for judges to say, but it must be observed that when people divide up on this question, where they stand depends heavily on where their ancestors stood on the English Civil War, and where their ancestors happened to be living during the so-called Pennamite Wars. As matters turned out, courts kept deciding in favor of Pennsylvania, and Connecticut kept bringing it up, again.

The Pennamite Wars: Who Had The Last Word?

|

| King Charles II |

Pennsylvania once fought three wars with Connecticut, but nowadays most people in both Connecticut and Pennsylvania have never heard of it. Those who do know, call them the Pennamite Wars. As you might expect, accounts by Connecticut patriots portray the matter as just taking possession of what they owned. Pennsylvania accounts of the wars, on the other hand, describe them as a stout defense against invasion. The matter boils down to the undisputed fact that King Charles II gave what is now the northern third of Pennsylvania to Connecticut in 1662, and in 1681 the same king gave it to William Penn. Eighty years after that, in 1769, Connecticut moved in, and Pennsylvania threw them out. It all happened twice more, and the Continental Congress became distressed that two of the thirteen colonial allies were fighting each other instead of the British. So it had to be resolved in court, and therefore we all have to get a little education in the fine points of real estate law in order to understand why Pennsylvania won the case. In short, Connecticut claimed that Charles II had cruelly and unjustly reversed himself, while the Penn Proprietorship simply maintained they were nonetheless legally entitled to the property.

Let's look at this dumb situation from the lawyers' point of view. If you own some land, but someone says you don't, your first response would be to show that the last owner turned it over to you without strings attached. And then you show that the title passed person-to-person backward in a clear chain of unclouded ownership. As long as this is provable, the critical deciding factor rests on what right the "original" owner had to it, from the Indians, or a King, or government charter. No one can be found to claim ownership earlier than that, so it must be yours.

The critical point is that "the original owner" is, therefore, the first private (non-governmental) owner. We are so used to this legal convention that it can be upsetting to discover that things were exactly opposite when we had a king -- and that our courts still uphold the monarch's decrees. Kings had a right to do absolutely anything, and that divine right, therefore, included the ability to revoke private ownership and take the property back or give it to someone else. Establishing a clear title is now a process of tracing back to the last moment when someone still had an absolute right to do anything he pleased with it. If what he did was cruel and unjust, too bad.

As soon as you trace your title back to a king or other absolute tyrant, the courtroom situation effectively reverses. At that critical turning point, the important issue stops being what a still-earlier owner intended and becomes what the final owner said. The last word of the last monarch extinguishes anything intended by anybody earlier. Even after all this ponderous logic is thoroughly explained, perhaps even repeated, the loser of a case goes away dissatisfied and angry. It ain't right.

It is right, of course, since you can't be an absolute monarch if you can't do what you please. If someone was an absolute monarch in the past, whatever he said was his right, and it would be disruptive to overturn in retrospect what seemed perfectly orderly at the time. The whole progress from Magna Carta to American Revolution was to accept old confiscations as final, as the necessary price of putting an end to having any new ones. After the cutoff point, the right to transfer property became the sole discretion of the current owner. The transfer of sovereignty from governmental to individual ownership was a serious main issue in the Revolutionary War.

Pennsylvania thus fought three Pennamite wars with Connecticut over conflicting land grants by kings, and also got into hot but non-military quarrels with Virginia and Maryland over much the same issues. If Pennsylvania had lost these disputes, the Commonwealth would now be little more than an eighth its present size. Pittsburgh would be in Virginia, Scranton would be in Connecticut, and Philadelphia would be a city in Maryland. Perhaps that wouldn't be so bad -- after all, maybe they don't have a city wage tax in Maryland.

What would be very bad, and therefore is the heart of the matter, is that we probably would have undergone two hundred years of contested titles and maybe even shooting wars, as a result of having property ownership in constant dispute. After a couple of generations, it matters less who was right and who was wrong. What begins to matter more is that things get fairly and finally settled so everyone can get on with his life.

The First Pennamite War (1769-1771)

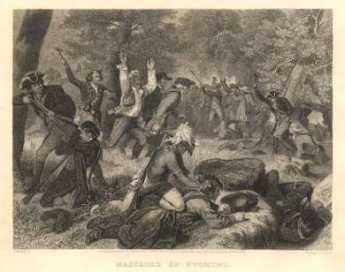

|

| The Wyoming Valley Massacre |

Things seemed peaceful in the Wyoming Valley for half a dozen years after the massacre, so Connecticut settlers slowly drifted back. This time, the people who didn't like poachers were the Proprietors of Pennsylvania. The Penn's were no longer Quakers, did not control the State Government, and in fact, were often in conflict with the Pennsylvania Quakers who had bought their land. They had to act as private citizens in their effort to expel the Connecticut poachers, which in this case meant calling Sheriff Jennings to evict them. Since everyone on the frontier in those days was armed and ready to fight, Jennings brought along a band of soldiers, led by Captain Amos Ogden.

On five different occasions, with escalating casualties, Jennings would arrest the settlers and take them before a judge in Easton, while Ogden stayed behind and burned the cabins and farm buildings to the ground, following which a somewhat larger group of Connecticut Yankees would return to the Wyoming Valley. By 1771, the Connecticut squatters had grown too numerous to be intimidated easily, and were militarily organized under an effective soldier, Zebulon Butler. Butler's men surrounded the handful of Pennsylvania soldiers in a fort under Ogden. At that point, Ogden briefly became a hero.

Seeing that reinforcements would be necessary, Ogden stripped naked, wrapped his clothes in a bundle around some sticks, and tied his hat on top. Tying a rope to the bundle, he floated down the river while the Connecticut sharpshooters peppered his hat with holes. Luckily, their aim was excellent, and Ogden escaped without being hit by a stray bullet. Off to Philadelphia for reinforcements.

Unfortunately, when Ogden and two hundred soldiers returned, Zebulon Butler ambushed them. In those days of honorable combat, Ogden was set free in recognition of his derringer-do, but only on the condition that he promised never to return. The Connecticut group was thus left in possession of the valley, and can fairly be said to have won the first war.

Litchfield County, Extended (1771-1775)

|

| Wilkes-Barre |

FOR four years, the Connecticut settlers considered the apparently peaceful Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania to be part of Litchfield County, Connecticut, and its main little town was called Westmoreland (now Wilkes-Barre, although it still has a Westmoreland Club). However, the high-living, non-Quaker sons of William Penn were ill content to let matters remain that way. Their response was to sell large tracts of land in the area, on condition the purchasers would do whatever fighting was needed to conquer and hold it. The main purchasers were Scotch-Irish from Lancaster County, and the main speculators were prominent Philadelphians with names like Francis, Tilghman, Shippen, Allen, Morris, and Biddle. This speculative land sale was to be the source of trouble for decades because it conflicted with titles to the same land issued by the Susquehanna Company.

The predictable trouble surfaced in 1775, with the Second Pennamite War. Under the command of a man named >Plunkett, 700 Pennsylvania soldiers marched to liberate Wyoming and were soundly defeated by the Connecticut soldiery under the command of Zebulon Butler. There might have been further fighting in this expanded war, except for the other eleven colonies applying great pressure on these two colonies fighting each other with potential jeopardy to the united rebellion against British rule. While the Penn family were definitely royalist in their sympathies, their colonial property put them in an awkward position with their Scotch-Irish allies, who were, in all colonies, the main leaders in the revolution. The effect was to isolate the Connecticut invaders, even though they were the victors in the fighting.

Litchfield's Past

|

| King Charles II |

The state of Connecticut absolutely loathes the idea that it is influenced by neighboring New York City. But Greenwich is full of hedge funds escaping high taxes, unfortunately not by very much. New Canaan is what Greenwich used to be, a snooty New York suburb. And Litchfield seems destined to be next in line, but still able to deny it. It's charming, neatly manicured, but still affordable. Young investment bankers think of buying a weekend home there, which will become New Canaan or Greenwich by the time they retire, which on Wall Street is often sooner than they guess. Meanwhile, the restaurants struggle to present an upscale appearance. The local law school claims to be the first in America. In spite of civil appearances, however, this is the town that decided to invade Pennsylvania on three different occasions, provoking massacres of several hundred people. Litchfield derives from Lichtfeld, a place where heretics are burned. When those dreadful Baptists from Rhode Island made an appearance, the local Congregationalists were ready to take a stand. The borders of Litchfield once extended west to Wilkes Barre, but it is still puzzling to ask how these invaders crossed the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Or how settler families marched through what is still pretty much a barren wilderness. All the while, telling themselves their destination was a paradise when even neighboring Scranton today looks down its nose at Wilkes Barre. What is this invasion trip like today, and why in the world would the Connecticut Yankees have changed it, three times?

|

| King Henry IV |

Those Yankees were almost certainly indifferent to the magnificent scenery offered the traveler of this path, especially when the fall foliage is awe-inspiring. George Washington's headquarters was to be located later at Newburgh for longer than at any other place, and thus it became the first national park monument in the country, lying across the path of the largely forgotten invaders. Unfortunately, hardly anyone even today in Connecticut knows what was notable back then, or cares to learn. Connecticut may make its living on Wall Street, but in a spiritual sense, it faces Boston. Curators at the National Park at Newburgh likewise know nothing of the Pennamite Wars. Restaurants have difficulty summoning up a hamburger; the motorist must pump his own gas. But there are clues; at least six different towns along the invasion route call themselves Milford, or New Milford, or similar. The postal service frowns on using the same name twice in a single state, else surely there would be more Milford. There are other clues. Near the end of the trip to the Wyoming Valley, can be found the "Promised Land Park". It's just past a place called "The Lord's Valley". Not far away can be found in the town of Dallas. Just why did Wilkes Barre name so many things after other places far away?

|

| White Flower Farm |

Perhaps the law school has something to do with it. Charles II of England had given Connecticut all the land to the Pacific Ocean when it was all wilderness that just about nobody wanted to own. Eighteen years later, the same king gave the same land to William Penn. Any modern lawyer, and maybe those backwoods lawyers three centuries ago, would tell you that if the King gave it away, it was no longer his. But Penn went to court with the complaint that the present king had just given it to him, and the court agreed that Penn could call the Sheriff to throw the Connecticut people out. Modern citizens would suspect bribery or other foul play, and perhaps the Yankees did, too. After all, ancestors of that King had badly mistreated some of their ancestors, so perhaps he held a grudge. Unfortunately, that's not how the law saw things at the time, and it's not entirely likely the Connecticut Yankees were being calm and straight about it. The fact was that Connecticut farmland never had much topsoil, and by this time it was worn out. Population growth pushed, and some fanciful tales of Wyoming (now Wilkes Barre) Valley's abandoned richness, pulled. They needed it, they wanted it, no one else was using it, the owner was already rich enough, and -- King Charles, that rascal, had given it to them.

The Connecticut Yankees liked to read books, so let them read Shakespeare. The so-called Henriad, those four plays concerning Henry IV and V in the 15th century, describes accurately how the King of England owned the whole island, by inheritance and by force of arms. Those nobles who followed him and brought along enough troops to win battles were each given a piece of the kingdom. But if, as quite regularly happened, one of the nobles betrayed or displeased the King, he lost his head, and his land was given to someone else. That's what it meant to be the King, and that's still largely the way it was in the Seventeenth, even early Eighteenth, century. It's true the Barons forced a king at Runnymede to obey the laws himself, Parliament asserted itself in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries, the open country began to be enclosed for private ownership in the Eighteenth century -- and the fellow colonists in America would ultimately break loose from England to extend these property rights further, until in 1787 the Constitution made it final. But that's a long way from saying King Charles II couldn't do what he pleased at the time he did it, and how many girlfriends he happened to have was irrelevant to the case. William Penn was a better lawyer than anyone in Litchfield and won the case every time it came up.

And furthermore, the Connecticut folks were out of step with their friends. Eleven of the colonies were fighting for independence, and George Washington was not alone in despairing that the other two colonies were fighting, not the British, but each other. Litchfield may now have the most beautiful flower farm market in America, but at the other end of the same street, the professional forebears of the Litchfield Law School were once giving poor advice.

Litchfield to Wilkes Barre, Today

To go from Connecticut to Pennsylvania without going through New York City seems at first a puzzling proposal. After all, New York is in the way. But a couple of centuries ago the Connecticut Yankees really did make it through the mountains, fought three little wars called the Pennamite Wars, and briefly made Wilkes Barre into part of Litchfield County. Because there has been comparatively little settlement along the trail, taking the trip today is the same mostly mountainous, journey. There are no Indians, but the mountains and rivers are the same. You still have to cross the Hudson, Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers but it's a beautiful trip at any time, particularly so during the autumn leaf season. Litchfield to Wilkes Barre: Millions of people live within a day's drive, but it's a good idea to pack a box lunch and fill your tank before leaving.

The Wyoming Massacre of July 3, 1778

|

| The Wyoming Massacre |

The six nations of Iroquois dominated Northeastern America by the same means the Incas dominated Peru -- commanding the headwaters of several rivers, the Hudson, the Delaware, and the Susquehanna, as well as the long finger lakes of New York, leading like rivers toward Lakes Ontario and Erie. They were thus able to strike quickly by canoe over a large territory. Iroquois were quite loyal to the British because of the efforts of Sir William Johnson, who settled among them and helped them advance to quite a sophisticated civilization. It even seems likely that another fifty years of peace would have brought them to an approximately western level of culture. Aside from Johnson, who was treated as almost a God, their leader was a Dartmouth graduate named Brant.

Brant, The Noble Savage

The mixed nature of the Iroquois is illustrated by the fact, on the one hand, that Sachem Brant translated the Bible into Mohawk and traveled in England raising money for his church. On the other hand, his biographers trouble to praise him for never killing women and children with his own hands. British loyalty to these fierce but promising pupils was one of the main reasons for the 1768 proclamation forbidding colonist settlement to the West of what we now call the Appalachian Trail, which on the other hand was itself one of the main grievances of the rebellious land-speculating colonists. The Indians, for their part, saw the proclamation line as their last hope for survival. After Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, the Indian allies were free to, and probably urged to, attack Wyoming Valley.

It is now politically incorrect to dwell on Indian massacres, but this one was both exceptionally savage, and very close to home. The Iroquois set about systematically exterminating the rather large Connecticut sub-colony and came pretty close to doing so. Children were thrown into bonfires, women were systematically scalped and butchered. The common soldiers who survived were forced to lie on a flat rock while Queen Esther, "a squaw of political prominence, passed around the circle singing a war-song and dashing out their brains." That was for common soldiers. The officers were singled out and shot in the thigh bone so they would be available to be tortured to death after the battle. The Wyoming Massacre was a hideous event, by any standard, and it went on for days afterward, as fugitives were hunted down and outlying settlements burned to the ground.

It's pretty hard to defend a massacre of this degree of savagery, but the Indians did have a point. They quite rightly saw that white settler penetration of the Proclamation Line would inevitably lead to more penetration, and eventually to the total loss of their homeland. The defeat of a whole British Army under Burgoyne showed them that they were all alone. It was do or die, now or never. Countless other civilizations have been extinguished by provoking a remorseless revenge in preference to a meek surrender.

Wilkes-Barre, Site of the Wyoming Massacre

|

| Wyoming Massacre |

For eons of time, the site of Wilkes-Barre, PA was once a sort of finger-lake between two mountain ridges. As dammed-up rivers tend to do, this one gradually filled up with sludge until the water spilled over at Nanticoke, a few miles to the south. After the lake drained out leaving the original river in place, there was also left a flat and fertile valley on either side of it. Furthermore, the towering mountain ranges on either side protected the valley from the weather, so the Wyoming Valley became a verdant paradise in the middle of the mountains. Somehow, the Congregationalist settlers of Connecticut found out about it, dug up some old deeds from King Charles to the effect it belonged to Connecticut, and eventually set forth to resettle in this mountain valley. Pennsylvania took offense at this, and the result was three little wars which few people have heard of, called the Pennamite Wars. The local Indians were most offended of all and did the most massacring in a very thorough way. During the Third Pennamite War, George Washington was at Valley Forge with more urgent matters on his mind, and dispatched General Sullivan to "take care" of the Indian problem; Sullivan did so in a very thorough way, essentially destroying the Iroquois nation. The other eleven colonies were distraught to see Pennsylvania and Connecticut putting on a side-show, and part of the judicial settlement was to give Connecticut the "Western Reserve" in Ohio as compensation for restoring the peace. The American Constitution of 1787 essentially made state possession of land a moot point, and the Western Reserve is just a quaint term you hear in Cleveland. Wyoming is a term that most people associate with a Western State, although it is named for this valley, and Dallas is another term that has been largely transplanted from a small town near Wilkes-Barre to a big town in Texas. So, if you want to get the confusion of terms straight, about Wyoming, Dallas, Western Reserve, and Westmoreland, you will take a little time to learn about Wilkes-Barre. Westmoreland is the name of gentleman's club in Wilkes-Barre, but it is also the name of a county near Pittsburgh where Connecticut folks thought it would be useful to flee.

That's a lot of history for a little town, but there's more. Somehow, the joys and pleasures of living in the Wyoming Valley were carried back to people like Rousseau, who were looking for examples of the "noble savage", noble because he had not learned all of the evil things that French aristocrats invented, and therefore warranted effusive praise during the so-called Romantic Period, when France was being purified by the guillotine. The main drum-beater for this mania was a poet named Thomas Campbell, who composed a long poem in Spencerian rhyme called "Gertrude of Pennsylvania". Even those who find merit in Spencer will nowadays find it difficult to accept the notion of flamingos on Pennsylvania streams, or lying on the ocean beaches of Pennsylvania, reading Shakespeare. Even those who have less taste for Herbert Spenser will still find a reason to distrust the judgment of those who praise the beheading of, say, Lavoisier. The noble savages in this particular case were Iroquois, who exterminated 600 settlers by essentially torturing them to death.

|

| General John Sullivan |

There's a memorial in nearby Wyoming commemorating this massacre, which indeed is probably better left forgotten. There are plaques with the names of the fallen, and the names of the survivors. The idea of the Wyoming Valley as a paradise on earth was destroyed by another event. The ancient lake which once filled the Wyoming Valley was deeper and more ancient than anyone guessed. Underneath the rich topsoil was a vein of anthracite, and Wilkes-Barre became a boom town with strip mining, a fate no paradise can long withstand. There is nearby said to be a coal mine which caught fire underground and has been burning uncontrolled for several decades. Talk about pollution disasters; this one is a monster.

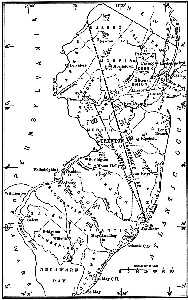

Reliable records of how the Connecticut Yankees got to the Wyoming Valley are hard to find. Offhand, it is puzzling to wonder how they got past New York or crossed the Hudson River. The best way to get between the two places today is probably pretty close to the route the colonists took, however, because travel in those days was much more constrained by geography. We know they started from Litchfield, CN, and in fact, for a while, Wilkes-Barre was part of the County of Litchfield. From Litchfield, they likely crossed the Hudson near Newburgh, went to the mountain gap at Port Jervis, and either came into the Wyoming Valley over the ridges or went a little north to the Susquehanna and came down from there. On a map at least, that's a relatively straight shot.

Wyoming, Fair Wilkes Barre

|

| Wyoming Valley |

There are a dozen or so places on the planet where a natural bowl formation famously moderates the climate. Cuernavaca in Mexico, the Canary Islands, and Chungking in Western China all claim to have temperatures which range from 70 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit, year-round. In Cuernavaca at least, they claim it only rains at night. These three places have a high plateau in the center of a mountain bowl, like an angel food cake pan, which may (or may not) contribute to the unusually mild climate effect. Several other places within inner China compete for the title of Shangri La, famous in song and story, never precisely located by tourists. The Wyoming Valley of the Susquehanna River once enjoyed a similar luster during the Romantic Period at the very beginning of the Nineteenth century, although unfortunately, its temperature is plainly not so balmy. Wyoming of song and poem was imagined to be the home of the Noble Savage, unstained by the wayward influences of civilization, and thus a model for the democratic ideal expected to emerge in Old Europe once the aristocrats were exterminated by nature's noblemen, European version. That seems to have been Robespierre in France, as disappointing to idealists as the Iroquois along the Susquehanna.

|

| Massacre Monument |

But one must not scoff. The Wyoming Valley was created long ago by a lake between two mountain ridges, which gradually dried up leaving flat topsoil deep at the bottom of the valley when the river finally broke through at Nanticoke and drained it. Its appearance is enhanced by surroundings in all directions of at least fifty miles of bleakness. Nowadays, the best way to appreciate the natural beauty of the place is to arrive from the south, gaining the summit of the ridge by one of the secondary roads. Housing development down below stops at the edge of the level plain, so as one ascends to the southern rim it is possible to see the inside of the bowl without seeing much of the town, and thus appreciate how it must have looked to frontiersmen searching for likely places to settle. It's quite beautiful. Descending into the bowl, the potholes in the road and roadhouses along the way to begin to make an impression. In full sight, it looks as though a city suburb has filled the place to its edge, with a rather decaying Nineteenth-century town center, but towering wooded mountainsides. There's a quiet park in the very center, through which the quiet river runs. In a little subdivision named Wyoming, there is a monument to The Massacre, now described as a hopeless defense by untrained Revolutionaries against the fearsome Indians and British Loyalists. The names of the fallen and the names of those who escaped are carved on this monument near Forty Fort. One presumes the wounded and some bystanders were massacred, the officers and trained infantry were more likely to escape the hopeless odds by fleeing into the woods. It is claimed that common soldiers were finished off by Indian Queen Esther smashing their heads between two flat rocks. Wounded officers were tortured to death.

|

| Delaware Water Gap at Stroudsburg |

Just where the Connecticut immigrants, or invaders, first arrived in the Wyoming Valley is not known. Their most likely entrance was at the top of the northern end of the valley, where ski lodges now cluster, after coming up the mountains from the east. The hills rising from the Delaware watershed are wooded but too rocky for farming. It's therefore inexpensive to set aside parks named "Promised Land" and "The Lord's Valley" and such, with some Milford, scattered here and there in the woods. A section of the upper Delaware River fifty miles long, from Port Jervis down to the Delaware Water Gap at Stroudsburg is enclosed in a National Wildlife and Recreation Area of about a mile's width on either side of the river. It's surprising how little is said of this rather large national park close to two large metropolitan areas. No doubt the visitors are torn between wishing it was more appreciated, and hoping to keep it secret and unspoiled.

|

| Wyoming Massacre |

The Decision of Trenton(1782) simply gave the disputed land back to Pennsylvania. There is a strong presumption the Connecticut migrants were privately promised land in the Western Reserve, in Ohio, whenever Ohio became a state. In spite of the implicit guarantees, the Pennsylvanians nevertheless treated the usurpers pretty roughly, and traces of Connecticut trail westward toward the Ohio line. There's a Westmoreland County near Pittsburgh, where many stranded families in the bituminous coal regions can thus trace their ancestry back to the Mayflower. It is truly extraordinary that such bitterness could leave so little trace of itself later. History may not be bunk, but persistent grievances are surely a menace to a peaceful existence. The events of the Pennamite Wars are widely believed to have led to the slanting of the 1787 Constitution toward the protection of individual property rights, but the wording to that effect within the Constitution is hard to locate. Somehow, like the implicit promises of the Western Reserve, ways were found to provide credible promises that it soon wouldn't matter which state you lived in. Somehow the word got to John Marshall that in actual practice, what would matter was whether an identified person could demonstrate clear title to specific land back to, or a little beyond, 1787, no matter what state the land was in. And the obscurity of the complex connection between this revolution in the law of property, and the very sad events in the Wyoming Valley suited everybody concerned. Stare decisis.

Wyoming, Fair Wyoming Valley

|

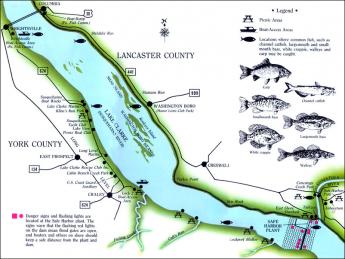

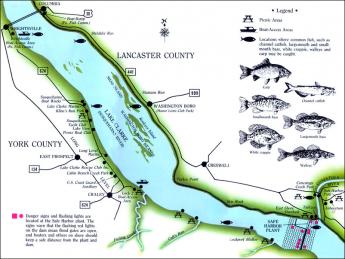

| Lake Clarke |

By 1750, or roughly ninety years after King Charles gave them their charter extending infinitely to the Pacific Ocean, the Connecticut Yankees with Old Testament first names had found their promised land was as disappointing as the King who promised it to them. So, two kings later, an exploratory party was sent west of the Hudson. The party returned with glowing tales of the Wyoming Valley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, just over the Blue Ridge Mountain. Only one white man had ever been there before them, Count Zinzendorf, the adventurous founder of the Moravian Sect.

|

| Iroquois |

The Wyoming Valley is certainly a jewel. It has comparatively mild weather as a result of being protected on all sides by mountains. The Susquehanna River runs through it, pinched by narrow valleys at both the top and the bottom, and filled with deep rich topsoil. In fact, it constitutes the remains of an ancient lake, whose Southern tip had broken through the Nanticoke Gap, draining the lake. It took another century or so to learn that underneath the topsoil was a thick deposit of anthracite coal. The Connecticut explorers were ecstatic about this little paradise in the mountains, and returned with news that it was everything the real estate promoters (The Susquehanna Company) wanted to hear. Indeed, the promotion of this valley almost got out of hand when news of it reached Europe at the start of the Romantic Period. Wyoming is what everybody wanted to hear about, the home of the noble savage. An epic poet named Thomas Campbell composed a long saga about Gertrude of Wyoming that caught the fancy of the Romanticists, with tales of Gertrude luxuriating on the ocean beaches of Pennsylvania, watching flocks of pink flamingos, and similar fancies, like Gertrude reading Shakespeare in the woods. In 1762 The Susquehanna Company sold six hundred shares to Connecticut adventurers, who were soon off to paradise.

The noble savages turned out to be Iroquois, who watched the new settlers on their land from behind neighboring trees. After a few months it became clear the white settlers intended to stay permanently in the valley, so one day the Indians emerged from the woods, and annihilated them.

The Third Pennamite War (1778-1784)

|

| Wyoming massacre |

And so, after the Revolution was finally over, there was a third war between Pennsylvanians and the Connecticut born settlers of the Wyoming Valley. This time, the disputes were focused on, not the land grants of King Charles but the 1771 land sales by Penn family, most of which conflicted with land sales to the Connecticut settlers by the Susquehanna Company. The Connecticut settlers felt they had paid for the land in good faith and had certainly suffered to defend it against the common enemy. The Pennsylvanians were composed of speculators (mostly in Philadelphia) and settlers (mostly Scotch-Irish from Lancaster County). Between them, these two groups easily controlled the votes in the Pennsylvania Assembly, leading to some outrageous political behavior which conferred legal justification on disgraceful vigilante behavior. For example, once the American Revolution was finally over (1783) the Decision of Trenton had given clear control to Pennsylvania, so its Assembly appointed two ruffians named Patterson and Armstrong to be commissioners in the Wyoming Valley. These two promptly gave the settlers six months to leave the land, and using a slight show of resistance as sufficient pretext, burned the buildings and scattered the inhabitants, killing a number of them. One of the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation was thus promptly demonstrated, as well as the ensuing importance of a little-understood provision of the new (1787) Constitution . No state may now interfere in the provisions of private contracts. Those with nostalgia for states rights must overcome a heavy burden of history about what state legislatures were capable of doing in this and similar matters, in the days before the federal government was empowered to stop it.

A flood soon wiped out most of the landmarks in the Wyoming Valley, and it had to be resurveyed. Patterson, whose official letters to the Assembly denounced the Connecticut settlers as bandits, perjurers, ruffians, and a despicable herd, boasted that he had restored, to what he called his constituents, "the chief part of all the lands". The scattered settlers nevertheless began to trickle back to the Valley, and Patterson had several of them whipped with ramrods. As the settlers became more numerous, Armstrong marched a small army up from Lancaster. He pledged to the settlers on his honor as a gentleman that if both sides disarmed, he would restore order. As soon as the Connecticut group had surrendered their weapons, they were imprisoned; Patterson's soldiers were not disarmed at all and assisted the process of marching the Connecticut settlers, chained together, to prison in Easton and Sunbury. To its everlasting credit, the decent element of Pennsylvania was incensed by this disgraceful behavior; the prisoners somehow mysteriously were allowed to escape, and the Assembly was cowed by the general outrage into recalling Patterson and Armstrong. Finally, the indignation spread to New York and Massachusetts, where a strong movement developed to carve out a new state in Pennsylvania's Northeast, to put a stop to dissension which threatened the unity of the whole nation. That was a credible threat, and the Pennsylvania Assembly appeared to back down, giving titles to the settlers in what was called the "Confirming Act of 1787". Unfortunately, in what has since become almost a tradition in the Pennsylvania legislature, the law was intentionally unconstitutional. Among other things, it gave some settlers land in compensation that belonged to other settlers, violating the provision in the new Constitution against "private takings", once again displaying the superiority of the Constitution over the Articles of Confederation. It is quite clear that the legislators knew very well that after a protracted period of litigation, the courts would eventually strike this provision down, so it was safe to offer it as a compromise and take credit for being reasonable.

It is useful to remember that the Pennsylvania legislature and the Founding Fathers were meeting in the same building at 6th and Chestnut Streets, sometimes at the same moment. Books really need to be written to dramatize the contrast between the motivations and behavior of the sly, duplicitous Assembly, and the other group of men living in nearby rooming houses who had pledged their lives and sacred honor to establish and preserve democracy. To remember this curious contrast is to help understand Benjamin Franklin's disdainful remarks about parliaments and legislatures in general, not merely this one of which he had once been Majority Leader. The deliberations of the Constitutional Convention were kept a secret, allowing Franklin the latitude to point out the serious weaknesses of real-life parliamentary process, and supplying hideous examples, just next door, of what he was talking about.

Sullivan's March

|

| Sullivan |

George Washington had plenty of other problems to contend with in 1778, but an Indian uprising led by Loyalists was too much. He singled out General John Sullivan, a celebrated Indian fighter from New Hampshire, gave him four thousand troops, and told him to eliminate this Indian threat to the Continental Army's rear, remove the safe haven for Loyalists, and assist the new Indian allies which LaFayette had befriended in the Albany area before the battle of Saratoga.

From long experience, Sullivan knew what to do, and did it without remorse. Ignoring skirmishes and ambushed sentries, he marched his troops from the scene of the massacre straight into the heart of Iroquois homeland, destroying every source of food or Indian settlement he could find. He was not interested in winning battles, he was determined to starve the Indians into extinction, once and for all. After these two slaughters, a white one in the Wyoming Valley (the Connecticut squatters in Wilkes-Barre), and now a red one in upstate New York, the entire frontier north of Pennsylvania has left a scene of devastation. Not much was heard of Indian fighting on this frontier for the rest of the Revolutionary War. Indeed, only the novels of James Fennimore Cooper make much subsequent mention of the Iroquois in American history.

Pennsylvania's First Industrial Revolution

|

| David Thomas |

We tend to think of 1776 as the beginning of American history, but in fact, the region around Easton was settled a hundred-forty years before 1776, and the forests were pretty well lumbered out. The backwoods lumbermen around the junction of the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers were about to move further west when Washington crossed Delaware and fought the battle of Trenton. This region nevertheless had three essential ingredients for becoming the "Arsenal of the Revolution": It was close to the war zone but protected by mountains, it had a network of rivers, and it had coal. The hard coal of Anthracite had the problem it was slow to catch fire, and iron making in the region didn't really get started big-time until a Welsh iron maker named David Thomas discovered that anthracite for iron making would work if the air blast was pre-heated before introducing it into a "blast" furnace. A local iron maker traveled to England to license the patent from Thomas, whereupon Thomas' wife persuaded her husband to move to Pennsylvania. Blast furnaces only got started into production by 1840, but by 1870 there were 55 furnaces along the Lehigh Canal. For thirty years this was America's greatest iron-producing region. In fact, Bethlehem Steel only closed its last plant in 1995.

|

| Canal Boat |

When iron-making got started, the local industrial revolution really took off, but the more fundamental step was to dig canals to transport the coal to other regions. Canals were the dominant form of transportation for only thirty years until railroads took over, and the entire Northeast of the nation was laced with canals. Curiously, the South had relatively few canals, so their industrialization was too late for canals, and too early for railroads, to help much in the Civil War. The Erie Canal was the big winner, but Pennsylvania had many networks of canals in competition, leading to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, whereas the Erie Canal was more headed toward the Great Lakes and Chicago. Eventually, J.P. Morgan put an end to this race by financing the Pennsylvania Railroad and moving the steel industry to Pittsburgh, where bituminous coal was the fuel of choice. This industrial rivalry was at the heart of the enduring rivalry of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, as well as the commercial rivalry between New York and Philadelphia. It was more or less the end of the flourishing economy of the "Reach" including Easton, Bethlehem, and Allentown. A reach is a geographic unit sort of bigger than a county, in local parlance. But you might as well include the city of Reading, which concentrated more on railroads and commerce with the Dutch Country. Out of danger from the British Fleet on the ocean, but close enough for war, the "reach" was more or less the forerunner of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Vietnam in several later wars. The Lehigh Canal stretched from Easton to Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe), the so-called Switzerland of Pennsylvania, only a mile or two West of the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

|

| Blue Mountain |

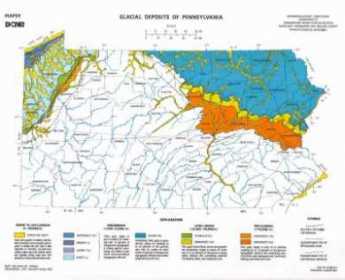

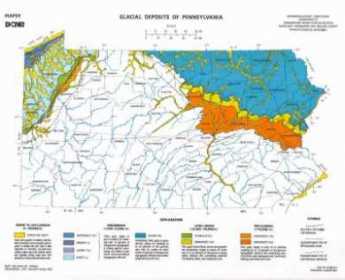

The Allegheny Mountains stretch across the State of Pennsylvania, and the most easterly of these mountains is locally called "Blue" mountain because of its hazy appearance from the East when seen across a lush and prosperous coastal plain. It represents the farthest extent of the several glaciers in the region, and the two sides of it present quite a sociological contrast. The Pennsylvania Dutch found themselves on the richest farming land in the world, whereas the inhabitants of the other side of the mountain had to subsist on pebbles. The mountain levels down at the Delaware River, so the Dutch farmers and the late immigrants from Central Europe mixed, in the time and region of industrial prosperity. Gradually, the miners and the steelworkers began to drift away, but the Pennsylvania Germans tended to remain where they had been before all the fuss. So the Kutztown Fair is full of Seven Sweets and Seven Sours, the farmhouses are large and ample, and mostly remain the way they were, too. You have little trouble finding a twang of Pennsylvania Dutch accents. But Bucks County in Pennsylvania was cut in half by the glacier, and north of the borderline, you can see lots of pickup trucks with gun racks behind the driver. Everything is amicable, you understand, but for some reason, the tax revenues of the two halves of the County are forbidden to be transferred, even within the same county. Better that way.

|

| Lehigh Marker |

The Lehigh River runs along the North side of Blue Mountain, and trickles down to join the Delaware at the town of Easton. There were only 11 houses in the town in 1776, and now you can see several miles of formerly elegant early Nineteenth century townhouses. At the point where the two rivers join, a lovely little park has been built to celebrate the high point of Colonial canal-making. Hugh Moore, the founder of the Dixie Cup Company is responsible for this historic memory, well worth a trip to see. If you have called ahead for reservations, you can have a genuine canal boat ride, pulled by two genuine mules. When you hear that the boat captain and his family used to live on the boat (Poppa steered, Momma, cooked, and the children tended the mules), it seems small and cramped. But when you climb aboard, you find it holds a hundred people for dinner with plates in their laps. The food is partly Polish, partly Hungarian and partly other things Central European. And the captain plays guitar and fiddle, singing old songs he mostly composed himself. Surprisingly, no Stephen Foster, who held forth about four hundred miles to the West, until he drank himself to death at Bellevue Hospital in New York. Foster was a member of a rival tribe of canal boaters, the ones who traveled down to Pittsburgh via the Erie Canal. Along the Reach, you hear about three canals, the Lehigh, Delaware, and Morris. The first two are obvious enough since they and the railroads which subsequently followed ran along the banks of two rivers joined. The Morris was Robert Morris, at one time the richest man in America, who bought Morrisville across from Trenton on the speculation he could persuade his friends to put the Nation's Capital there. It didn't work out, so he bought and went broke with the District of Columbia. Anyway, the Morris canal went on to New York harbor, where it prospered mightily shipping iron to New York, and iron for the rolling mills of Boston. The Morris Canal went over the Delaware River on a bridge that carried an aqueduct, over to Philipsburg; and then across the wasp waist of New Jersey.

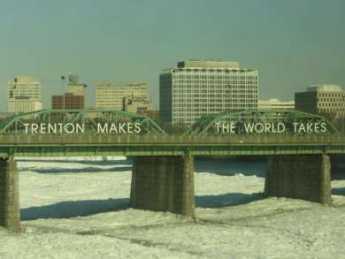

The Decision of Trenton (1782) Under the Articles of Confederation

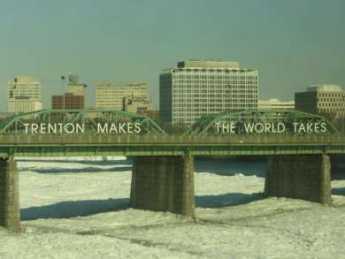

|

| Trenton Makes the World Takes |

AS the American Revolution drew to an end, the time arrived to settle the inter-state grievance of Pennsylvania and Connecticut over King Charles II's ambiguity about who owned Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley, including the city of Wilkes-Barre. However, if they were all going to be United States citizens, it didn't matter much whether the residents of Wilkes-Barre (as it was now known) were governed by the laws of Connecticut or Pennsylvania. But bloody grievances die hard, and slowly. The genteel debates envisioned by the Articles of Confederation were not equal to settling blood feuds, but they tried. The two states selected judges to represent them, in a negotiated settlement which took place on neutral ground, Trenton, New Jersey. After protracted testimony and prolonged secret deliberation, the judges emerged with a very brief and unexplained decision: The Wyoming Valley belongs to Pennsylvania. Period.

Almost every scholar of this subject is convinced that the unwritten decision contained two other provisions. Connecticut was given a piece of Ohio, Western Reserve. And the Pennsylvania representatives privately assured the group that the Pennsylvania Legislature would in time recognize the land titles of the Connecticut settlers who were actually resident on Pennsylvania land. Unfortunately, it is hard if not impossible to enforce an agreement that is secret, and the Connecticut claim to Ohio was eventually eliminated, while the Pennsylvania promise to recognize the land titles of people whose ancestors killed our ancestors, was much delayed, watered down, and resented.

Pennsylvania Likes Private Property Private

|

| William Penn Holding his Charter |

William Penn was the largest private landowner in America, maybe the whole world. He owned all of Pennsylvania, with the states of Delaware and New Jersey sort of thrown in. Although he and his descendants tried actively to sell off his real estate from 1684 to 1783, they still held an unsold three-fifths of it at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, which they were forced to sell to the state for about fifteen cents per acre. This bit of history partly explains both the strong feeling this is private, not communal, land despite the existence of 2.3 million acres of the state forest system, which is affirmed right alongside the rather inconsistent feeling that raw land is somehow inexhaustible. Early settlers regarded the center of the state as poor farmland, particularly when compared with soil found in Lancaster and Dauphin Counties, or anticipated by settlers going to Ohio and Southern Illinois. A complimentary description is that glaciers descended to about the middle of Pennsylvania, denuding the northern half of topsoil which was then dumped on the southern part as the glaciers receded. Even today, farmers tend to avoid the northern region if they can, reciting the ancient advice from their fathers that "Only a Mennonite can make a go of it, around there."

So, lumbering had a century-long flurry in Central Pennsylvania, exhausting the trees and moving on. But that only related to the top layer of soil; beneath it lay anthracite in the East, and bituminous coal in Western Pennsylvania, supporting the steel industries of the two ends of the state with exuberant railroad development. Even today worldwide, hauling coal is the chief money-maker for railroads. The resulting availability of rail transport promotes the location of heavy industry near coal regions; the 20th Century decline of coal demand ultimately hurried the decline of heavy industry in the state by impairing the railroads.

Beneath all this lie the aquifers, porous caverns of fresh water. And beneath that, largely unsuspected for two centuries, lie the sedimentary deposits of a huge inland sea, compressed into petroleum which evaporates into natural gas. All of this is held by huge deposits of semi-porous shale rock, now mostly 8000 feet deep, stretching from Canada to Texas and called the Marcellus shale formation. If it can be economically recovered, there is more natural gas than in Arabia, and there is a similar formation along the near side of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, stretching up to the Athabasca tar sands in Canada. There is another similar formation in France underneath Paris. No doubt, we will find the whole world has similar huge deposits for which the main problem has always been: how do you get it out?

There's another question, of course, of who owns it. Those who clearly do not own it maintain that everyone owns it. In the western world, most particularly in America, it is our firm belief that if you live on top of it, you own it. Since it is expensive to extract, quarrels like this are usually settled by purchasing mineral rights from the surface owner, who generally could not possibly extract it by himself. Those who assert they have a conflicting right to it because it belongs to everyone can expect belligerent resistance. At the present time when America faces a critical fifteen year period of dwindling oil supply, ultimately relieved by perfecting alternative energy sources, there is too little time to achieve consensus for any other governance theory. The problem which could possibly gain enough traction to interfere is the issue of potential damage to others which might result from the extraction of this subsurface treasure. Because of the apparent urgency of a decision to extract or go elsewhere to extract, the best we can hope for is some fairly rough justice.

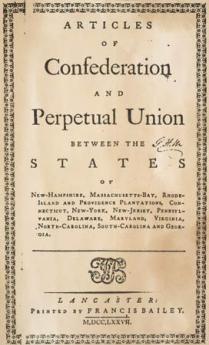

American Articles of Confederation, Valuable or Hindrance?

|

| Continental Congress |

THE British may well have been high-handed with their American colonies, but they were precise while enacting the Prohibitory Act of December 1775 about why they would attack militarily in 1776. Their American subjects had formed a rebel government in 1775 called the Continental Congress, which then dispatched an Army under George Washington to wage war against British forces in Boston; and then showed no signs of disbanding. What could you call that, except an armed mutiny?

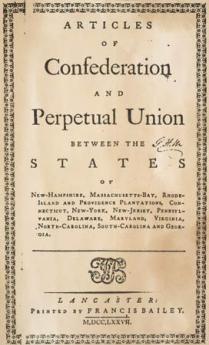

|

| Articles of Confederation |

The American colonists naturally had a different viewpoint. Because of the Prohibitory Act of 1775, they needed an established government of some sort to exist if war came, preferring not to be hanged for treason in defense of their rights as British subjects. Their primary grievance, at least at first, was taxation without representation. Many colonists were resistant to more than temporary independence from Britain. The most common goal of American moderates was then a variant of commonwealth similar to what was being discussed for Ireland. Once the British navy actually attacked, however, a strategic document describing what was contemplated for the far future was counter-productive. Strategic discussion bogged down into meaningless disputes between conservatives who wanted a strong central government, and radicals who argued for states' rights, neither of which was sufficiently tactical with British soldiers marauding the land.

To repeat the default position: Fighting the British fleet off Staten Island risked immediate hanging from the yardarm for treason, and the Articles of Confederation served the immediate purpose of legitimizing that. Lawyers may sometimes get lost in their own reasoning, but in this case, the advice was sound. Reconsidering the Articles after the Treaty of Paris was more appropriate, a smokescreen now only useful for confusing an angry British Admiral.

Although John Dickinson produced a workmanlike document in 1777 called the Articles of Confederation, it was weakened and not closely followed; formal ratification drifted during the first four years of the war. The chaotic situation also provided a pretext for some of the colonies to contribute less money or troops than their representatives promised. However, after five years of bloody warfare, an unratified Constitution became increasingly hard to justify, its disadvantages eventually outweighing any argument in favor. Robert Morris also decided the Articles needed to be ratified, as a sign of sufficient unity to justify long-term loans to them.

|

| Robert Morris |

Morris at that time was called the Financier, a poorly defined office which in his aggressive hands meant Morris was effectively running the country. His position put him in the center of unenforceable promises of aid from the thirteen states, justified to him in all the contradictory ways of beleaguered debtors. Morris was enough of a businessman to know that hard-pressed debtors frequently offer weak excuses. So, whether he felt he was thwarting phony evasions, or really believed the states had legal concerns, he pressed ahead vigorously for ratification of the Articles of Confederation. This was soon accomplished in 1781, but unfortunately, it made little difference. It can be safely surmised this experience hardened his long-expressed conviction that every federal government must at a minimum have realistic power to collect taxes to service its debts. But to accomplish that, now required those ratified Articles must be amended or replaced; he had made everything more difficult. It would now be six more years before the "perpetual" Articles could be unraveled, in the form of a new Constitution. That provided for federal taxation and going forward made it considerably easier to amend than by unanimous consent of all the states. There remained the awkwardness of that term "Perpetual". The whole experience was exasperating, but it surely left him and others determined not to be dissuaded by fine points of legal language.

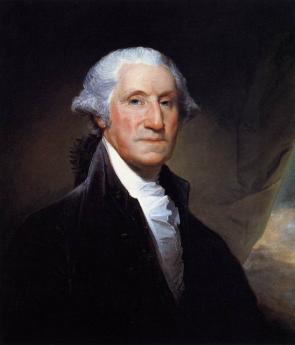

|

| George Washington |

Any perpetual agreement never to allow amendment (except by unanimous consent) is visibly unwise, but that was what confronted those who now proposed to amend the Articles. At the least, it pushed the decision in favor of replacing the whole document. It was easier to brush aside a perpetual legal document, as unreasonable than to argue that obtaining thirteen votes was impossible. George Washington had spent a lifetime constructing a reputation for always keeping his word. If even Washington could agree the situation was unreasonable, the public was of a mind to accept that absolutely anyone should agree. Anyway, the reasoning behind the language in the first place was that thirteen former colonies were joining together for a larger Union which would continue after the Revolution. It was the Union which was meant to be perpetual, not the Articles. Curiously, this change also made it easier to expand the union; imagine the difficulty of obtaining unanimous votes from fifty constituent states. There almost seems to be an ominous political axiom buried in this situation: as the number of voters grows, the majority margin must narrow if a deadlock is to be avoided.

The Revolutionary War, begun in 1775, continued from 1781 (Yorktown) to 1783. Even during four succeeding years of peaceful governance under the Articles, from the Treaty of Paris (1783) to the Constitutional Convention (1787), not a great deal happened. But a few things did come up to test the usefulness of the Articles. The small war between Connecticut and Pennsylvania was settled by the Decision of Trenton, although state boundaries became largely formalities after the country was unified by Article IV of the Constitution. The Northwest Ordinance was passed. And the Constitutional Convention was agreed to. Several flags were tested and adopted. Robert Morris had swept aside the habit of micro-managing the country by Congressional Committee, delegating government departments to bureaucracy in the process. Of all these activities, the most important was the Northwest Ordinance, which demonstrated that important governmental innovations could actually be accomplished under the Articles.

Democracies all like to talk too much. Their constitutions typically run to hundreds of micro-managed pages, and get everyone confused, unless they are unwritten, which is really confusing. It's hard to remember, but the Articles were the first written constitution, and to this day no other former member nation of the British Commonwealth has a written constitution. By giving things a trial run in the Articles of Confederation, we learned what is important and wrote it down. The second time around, tested in war and in peace, we made important revisions. By the time of the Civil War, we had a written governing document that men would die for because they understood it and approved.

Harvard Men Suggest a Cold Place for Yale

THE Colonial disputes with Great Britain were settled in 1783, creating great opportunities for the Colonies to resume their disputes with each other. Because of the unfortunate earlier action of the Penn Proprietors in selling land already occupied by Connecticut settlers, the legislatures of Connecticut and Pennsylvania behaved in ways that do them no credit. The situation could easily have led to more armed conflict, and it could even have gone from local war to fragmentation of the nation. So, although New York was close enough to know better, they joined with Massachusetts in offering to consider carving a new state out of Pennsylvania's northeast corner. The proposal was rejected, but the geological idea remains.

The northeast corner was once covered by glacier, and the region remains separated from the rest of Pennsylvania by a "terminal moraine", which is the huge pile of rocks and stones left behind after a glacier recedes. There are thirteen counties of rather desolate woods in this corner, with five or six more counties of moraine. Even today, some upper counties have only five or six thousand residents scattered in little settlements. The whole idea of creating a new state died when people got a chance to walk around and actually look at the region. Although one county is named Wyoming, this was not Wyoming, Fair Wyoming, at all; this was a pile of rocks. Moraines were what the Connecticut settlers were trying to escape.

However, their grandchildren might be unsure. Tremendous deposits of anthracite were soon discovered in the region, and then oil in Bradford County. Present residents of New York City will apparently commute endlessly to escape taxes, so an interstate highway or two would probably quickly make the area into Little Brooklyn.

The central point in all this was beginning to emerge. Since the Constitution was ratified, it simply no longer matters what state you were living in, as long as you can trust the legislature and the courts to be reasonably fair. These two combative legislatures and affiliated courts were once quite obviously behaving in a manner too obscenely partisan to be tolerated. Everybody involved in this mess could see the advantage offered by the ability to appeal to a superior power dominated by the other eleven (now, forty-nine) states. Carving out a separate state was not a compromise, at all. It was a threat, just as unsatisfactory to one combatant as the other.

Although it was clearly time to put aside the grievances and vengeances of a land dispute which had got out of hand, currents of other wild and headstrong ideas continued to swirl into the northeastern corner of Pennsylvania. In April 1786 Ethan Allen himself showed up in this region, wearing full Regimental uniform. He declared he had formed one new state and that with one hundred of his Green Mountain Boys and two hundred riflemen, he could establish another one. There is some reason to suppose Allen was responding to an action of the Susquehanna Company of Connecticut, which had held a meeting the previous September where Oliver Wolcott drafted a constitution for a new state named Westmoreland. William Judd was to be governor, John Franklin lieutenant governor and Ethan Allen was to be in command of the militia. The Assemblies of both Connecticut and Pennsylvania immediately reacted with outrage to renounce the whole State of Westmoreland idea; when John Franklin persisted, he was dragged to Philadelphia and thrown into jail to calm his rebellious spirit. Nevertheless, the point was dramatized that -- even five years after the Decision of Trenton had supposedly settled the matter, and after all sensible neighbors urgently wanted this dispute terminated -- something else needed to be done to strengthen the Articles of Confederation, or preferably replace them entirely.

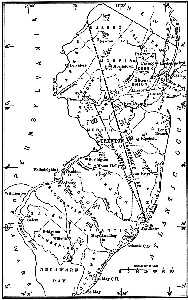

East Jersey's Decline and Fall

The colony of New Caesaria (Jersey) had two provinces, East and West Jersey, because the Stuart kings of England had given the colony to two of their friends, Sir George Carteret and John, Lord Berkeley, to split between them. Both provinces soon fell under the control of William Penn but it took a little longer to acquire the Berkeley part, so the Proprietorship of East Jersey was the oldest corporation in America until it dissolved in 1998.

|

| Apology for the True Christian Divinity |

It would appear that Penn intended West Jersey to be a refuge for English Quakers and East Jersey was to be the home of Scots Quakers. Twenty of the original twenty-four proprietors were Quakers, at least half of them Scottish. Early governorship of East Jersey was assumed by Robert Barclay, Laird of Urie, who was certainly Scottish enough for the purpose, and also a famous Quaker theologian. Even today, his Apology for the True Christian Divinity is regarded as the best statement of the original Quaker principles. However, Barclay remained in England, and his deputies proved to be somewhat more Scottish than Quaker. Eighteenth-century Scots were notoriously combative and soon engaged in serious disputes with the local Puritans who had earlier migrated into East Jersey from Connecticut with the encouragement of Carteret. This enclave of aggressive Puritans probably provided the path of migration for the Connecticut settlers who invaded Pennsylvania in the Pennamite Wars, so the hostility between Puritans and Quakers was soon established. The Dutch settlers in the region were also combative, so the eastern province of Penn's peaceful experiment in religious tolerance started off early with considerable unrest. Of these groups, the Scots became dominant, even referring to the region as New Scotland. To look ahead to the time of the Revolution, most of the East Jersey leadership was in the hands of Proprietors of Scottish derivation, with at least the advantage that these were likely to have been very vigilant in seeing Proprietor rights originally conferred by the British King, continue to be honored by the new American republic.

East Jersey was probably already the most diverse place in the colonies when loyalists and revolutionaries took opposite sides in the bitter eight-year war over English rule, with hatred further inflamed when the victors in the Revolution divvied up the properties of loyalists who had fled. The earlier conflict was created by management blunders of the Proprietary leadership itself. Instead of surveying and mapping, before they sold off defined property, like every other real estate development corporation, the East Jersey Proprietors adopted the bizarre practice of selling plots of land first and then telling the purchaser to select its location. In the early years, it is true that good farmland was abundant, but inevitably two or more purchasers would occasionally choose overlapping plots of land. The Proprietors were astonishingly indifferent to the resulting uproar, telling the purchasers that this was their problem. The outcome of all this friction was that settlers petitioned London for relief, and in 1703 Queen Anne took governing powers away from both the East and West proprietorships and unified the two provinces into a single crown colony. The Queen obviously nursed the hope that South Jersey would impose a civilizing influence on the North, but immigration patterns determined a somewhat opposite outcome. Both proprietorships, however, were allowed to continue full ownership rights to any remaining undeeded property.

In later years, the East Jersey Proprietors created more unnecessary problems by attempting to confiscate and re-sell pieces of land whose surveys were faulty, sometimes of a property occupied with houses for as much as fifty years. This East Jersey proprietorship, in short, did not enjoy either a low profile or the same level of benevolent acceptance prevailing in the West Jersey province. A climate of skepticism developed that easily turned any management misjudgment into a confrontation.

|

| New Jersey Line |

The East Jersey proprietorship operated by taking title to unclaimed land, and then reselling it. In what seemed like a minor difference, the West Jersey group never took title itself, but merely charged a fee for surveying and managing the sale of unclaimed land. The upshot of this distinction was that the East Jersey group got into many lawsuits over disputed ownership, which the West Jersey Proprietorship largely escaped. The nature of unclaimed land in New Jersey is for ocean currents to throw up new islands in the bays between the barrier islands and the mainland, or pile up new swampland along the banks of the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Such marshy and mosquito-infested land may have little value to a farmer but lately has become highly prized by environmentalists, who supply class-action lawyers with that nebulous legal concept of "standing". The posture of the West Jersey Proprietors is to be happy to survey and convey clear title to a particular property for a fee, but a buyer must come to them with that request. The East Jersey method put its proprietors in repeated conflict over possession and title, with idealists enjoying free legal encouragement from contingent-fee lawyers. By 1998, the Proprietors of East Jersey had endured all they could stand. Selling their remaining rights to the State for a nominal sum, they turned over their historic documents to the state archives. The plaintiff lawyers could sue the state for the swamps if they chose to, but the East Jersey Proprietors had just had enough.

The only clear thing about all of this is that the Proprietors of West Jersey now stand unchallenged as the oldest stockholder corporation in America. It's not certain just what this title is worth, but at least it is awfully hard to improve on it.

Gashouse Gang

|

| Electrician Union Logo |

A couple of lawyers from Community Legal Services dropped around to the Franklin Inn club, the other day. Someone in the club thought they might be able to shed some light on the recent sale, or rather frustrated sale, of the Philadelphia Gas Works and invited them over. They told us what they knew, but other luncheon guests came away with the impression they don't know the full scoop. It's for sure the newspapers don't know much, either.

|

| Philadelphia's Gas Company |

Philadelphia's Gas Company was started in 1830 and acquired as a City property in 1860. Before that time, an occasional mansion would have its own private gas house, fermenting gas for central lighting and heating, and apparently the scene of other carryings-on, leading to the derogatory title of "Gas House Gang". That was long before any thought of city corruption, or politics, or even professional Baseball. For nearly a century, municipal gas works would produce "Manufacturer's Gas" by fermentation of various discarded materials, but when the "Big Inch" pipeline was converted to natural gas at the end of the World War II, at least people stopped committing suicide with it (natural gas didn't work), and most cities sold the gas company to private owners. Gas work has long had the reputation of featherbedding and corruption, selective collection of gas bills, and a fair amount of graft. Perhaps much of this is a legend of the past, but I wouldn't bet much money on it. It suddenly got into the news lately, when a Connecticut company made a cash offer for PGW, the local gas company. The Mayor liked the idea and brought it to City Council, which refused even to consider it. The newspapers had recently had a run-in with Mr. Dougherty, the President of the Electricians Union, over the conviction of the union for arson of the Chestnut Hill Quaker Meeting House, and there's no doubt the news coverage of the Gashouse sale offered the public a dim perception of City Council politicians and their pro-union behavior.

|

| John Dougherty |

Our lawyer guests felt this was a little unfair. The Mayor did request a hearing on the matter, but he is not a member of City Council and needed a member to introduce the topic for discussion. After the Council President expressed an unfavorable position, no other member of Council was willing to introduce it. So the matter was dropped for lack of a sponsor. While there is little doubt much was beneath the surface, it is a little imprecise to say the Council blocked the matter from consideration. The next time the City Charter comes up for review, it would seem reasonable to allow the Mayor to introduce measures by himself, perhaps by giving him ex officio membership. Leaving him without some way to start a discussion, as he was humiliated to admit in public, does seem a little awkward. But it permits it to be said they actively blocked him, in this particular case.

|

| Gov. Tom Corbett |