1 Volumes

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

Quaker Peace Testimony

New topic 2016-12-04 04:05:49 description

Quakers Turn Their Backs on Power

There have been a number of excellent books about Ben Franklin lately, but all take his side in the dispute with Quakers. These authors relate Franklin struggled with the Quakers, fought with that political party, heroically overcame them with wisdom and guile. Good thing, too, or we all might still be subjects of the British crown.

Well, within the Quaker community these events are viewed differently. Around the year 1755, the Quakers who owned and ran Pennsylvania abruptly turned away from politics and left the government to their political enemies, rather than compromise religious principles. It is difficult to think of any other instance in history when a ruling party decided to become humble subjects of the opposing party, simply because they refused to do what obviously had to be done.

The background of this perplexing issue goes back to the founding of the Quaker colonies, which had lived in a real Utopia for seventy-five years. Repeatedly it had been true that if they just followed the highest principle, things worked out well for everybody. For example, they didn't need to buy the land a second time from the Indians, but they did, with the gratifying result of peaceful co-existence while other colonies experienced constant Indian wars. Penn negotiated the borders of his states with the neighbors, and although it took decades, brought peace and prosperous trade in return. Strict honesty in mercantile matters led to a reputation for trustworthiness, and that in turn led to prosperous commerce. Using a fixed price rather than haggling over price speeded up transactions, gained respect for fair dealing, led to more prosperity. Just you do the right thing, and all will be well. That includes extending freedom of religion, welcoming strangers to the colony to worship together in peace.

Toward the end of this Utopian period, some questions began to arise. More and more non-Quakers came to the colony, making the colony progressively less Quaker. That was a silent disappointment to William Penn. The founder had been a charismatic evangelist for his religion as a youth but came to grave disappointment about peaceful persuasion by the end of his life. Convincing the adherents of other religions of reasonable Quaker principles had often proved to be as intractably difficult as arguing religion with Henry VIII. The Quakers, a religion without a clergy, were appalled that so many adherents of other religions did not concern themselves with earnest reasoning, preferring to do strictly what their ministers told them to do.

Another disconcerting thought was growing within the Quaker community that success itself might be corrupting them. Worldliness seemed to grow inevitably out of wealth and prominence; all power does tend to corrupt. If you are rich, people always seem to steal from you, and that leads to violent punishments, something regrettable in itself. These were not new arguments, but by 1750 nearly a century of success in paradise had begun to stir Pennsylvania Quakers to wonder why more of their neighbors did not ask to become Members. These were troubling concerns of the day which would probably have worked themselves out, except that far-away France and England declared war on each other. The French responded by stirring up the Indians along the Western frontier. Pennsylvania settlers were soon scalped, kidnapped and burned at the stake. Something had to be done about it since protection was a duty of government, and effective protection now had to be non-peaceful. The Quakers dithered. More Scotch-Irish settlers around Pittsburgh were slaughtered. The Quaker meetings sent minutes to the Quakers in the legislature that they must not compromise their peaceful principles, and the Scotch-Irish exploded with rage. The Meetings told their representatives to resign from office, their members to retreat from politics altogether.

So Ben Franklin rose to the occasion, and General Forbes led an army to Fort Duquesne at the forks of Ohio, and Colonel George Washington was the hero of that day. The French were driven off the frontier, the English were victorious at Quebec. North America became a British continent.

Meanwhile, the Quakers retreated into tight-lipped solitude. And self-doubt, because the episode seemed to demonstrate that rigidly peaceful principles cannot govern a state or a nation if that nation contains others unwilling to be sacrificed for peaceful principles. An unthinkable logic emerged; freedom of religion led to conflict with the duty of a non-violent government to protect its citizens. It began to be clear it was the duty of government to enforce its laws, by force if necessary. Underneath the pile of documents, was a gun.

So, the Quakers proudly walked away from power and dominance, for all time. Sadly, too, because the significance was clear. Peaceful utopia may be not possible, within a dangerous world.

Pembertons

|

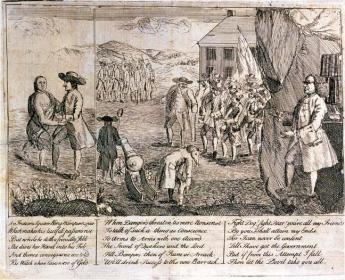

| Israel Pemberton, Ben Franklin satire l |

Ralph Pemberton was an English Quaker well before 1650; he may have been a Quaker before William Penn was one. As an old man, he accompanied his son Phineas to Pennsylvania in 1682. They established a farm on the banks of Delaware in Bucks County called Grove Place, and Phineas soon became one of the chief men in the colony. In the next generation, Israel Pemberton became one of the best educated, richest merchants in the colony. But it was Israel's son also called Israel, who earned the title of King of the Quakers. He was one of the founding Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital along with Benjamin Franklin and one of his brothers, James Pemberton, and was a generous philanthropist and leader of a number of other civic organizations. Just exactly what provoked his famous political disputes with Franklin is not clear, but he was a leading friend of the Indians, whom Franklin never much liked. Israel Pemberton strongly and effectively argued William Penn's policy of friendship with the Indians, particularly insisting that sales of land to colonists should be prevented until there was a clear agreement with the Indians about the ownership. Unfortunately, pressures built up as Europeans immigrated faster than this policy could accommodate smoothly, and Franklin mostly sided with the impatient immigrants -- and squatters. This disagreement came to a head in 1756 when Pemberton negotiated a treaty of peace with the Indians at a conference at Easton. Although this treaty seemed to settle matters, it came against a background of the descendants of William Penn abandoning Quakerism. They, however, remained the proprietary owners of the Province with a more narrow focus on speeding up land sales to maximize their investment. Much of the internal dynamics of these quarrels before the Revolutionary War remain unclear and possibly somewhat misrepresented.

|

| Shenandoah Valley |

When the Revolution came, Pemberton viewed it with disfavor, mostly for pacifist rather than purely Tory reasons. Feelings ran high since the Pembertons were influential citizens with the potential to dissuade wavering neighbors, which made it difficult to tolerate them as invisible bystanders. However that may be, the three Pemberton brothers and twenty other wealthy and influential Quakers were arrested and, without hearing or trial, thrown in the back of an oxcart and sent into exile in Virginia for eight months. Their journey was a curious one, along a trail up the Schuylkill to the ford at Pottstown, and then down the Shenandoah Valley, an area in which they were well known and highly respected, greeted with great sympathy as they traveled. Isaac's brother John, who had spent several years as a missionary, died during this exile.

|

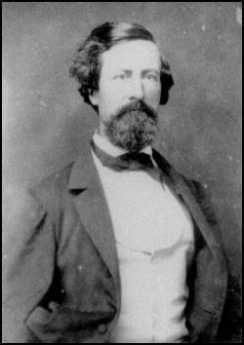

| John Clifford Pemberton |

In some ways, the most curiously notable Pemberton was John Clifford Pemberton, who applied to West Point on his own initiative and was appointed by Andrew Jackson who had been a friend of his father. In itself, it is curious that so combative a person and so vigorous an enemy of the Indians -- as Jackson certainly was -- would have Quaker friendships. But he did not misjudge John Clifford, who became a diligent professional warrior for his country in a number of military incidents with the Indians, the Mexicans, and the Canadians, rising to the rank of captain in the regular Army at the opening of the Civil War. In spite of personal efforts by General Winfield Scott to dissuade him, he resigned his commission and volunteered in the Confederate army. He was quickly promoted to major, then a brigadier general and eventually to Lieutenant General. As such, he was the commanding Confederate officer at the fifty-day siege of Vicksburg where he was finally forced to surrender to Grant's army. In a prisoner exchange, he was returned to the Confederate side, which they had no openings for Lieutenant Generals. He resigned and re-enlisted as a common soldier, but was quickly promoted to the rank of Colonel, in charge of the artillery at the final siege of Richmond. After the war, he became a farmer in Warrenton, Virginia, but was visiting at the family home in Penllyn when he died in 1881. John Clifford Pemberton, the highest-ranking general on the grounds, lies buried in Laurel Hill cemetery right next to Israel Pemberton. In some sort of triumph of the South, he here out-ranks George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg. Just how his pacifist family reconciled itself to his heroism can only be imagined.

Espionage in the Revolution

|

| John Nagy |

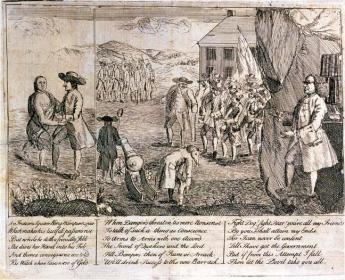

Both sides fighting the Revolutionary War predominantly spoke English as a native language, so it seemed deceptively simple to pick up a little cash for a tidbit of information or two. John Nagy, who has written several books on spies in the Revolution, recently addressed the Right Angle Club about this interesting topic. According to him, Quakers were favorites as spies because they were widely split in their sympathies, and as pacifists were abundant in the civilian societies of the time. Others have commented that the main difference between Conservatives and Free Quakers was that the Free Quakers were mostly of the artisan class and sympathetic to the Revolution, while the Conservatives were mainly of the merchant class, and Tories. But there were many exceptions, and the plain dress Quakers were hard to tell apart and passed freely through the military lines. No doubt many readers will be incensed by such comments, for which we take absolutely no responsibility.

|

| Beaumarchais |

The one main exception to the English-language generalization were the French, who were still smarting from their defeat in the Seven-Years (French and Indian) War. The playwright Beaumarchais was quite active in the French movement to make trouble for the hated English and seems to have stirred up King Louis XVI to be interested in financing rebel trouble-makers, if not to become active combatants. In any event, a wary King thought it was best to send a spy to look over the situation. As detailed in a little pamphlet called The Spy in Carpenter's Hall the Americans were tipped off about the plot. Accordingly, the spy named Bonvoloir was hidden up on the second floor of Carpenter's Hall, while the colonists put on a belligerent falsified performance on the first floor. It is claimed their performance was a convincing one, having the desired effect of creating a report to the King that the colonists were belligerent, warlike, numerous and united. After the Battles of Trenton and Saratoga, the timing was good for using this sort of report to provoke the King into doing what he was mostly of a mind to do, anyway.

|

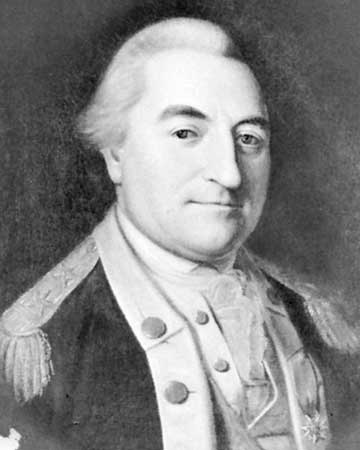

| Johann de Kalb |

The French were unusual in favoring aristocrats as spies and Johann de Kalb was anther who snooped around, returning later in the form of General de Kalb of military note. The names of British spies, aside from Major Andre, tended to have a Quaker sound to them, like Dunwoody, Cadwalader Jones and the like. It would take deep research to know whether these were Quaker stalwarts or merely black sheep of some family; there is little doubt that sympathies changed with the changing fortunes of battle. Another feature was the careless lying which took place for propaganda purposes. The famous story of Lydia Darragh, a Quaker who allegedly overheard the British officers plotting the surprise attack on Whitemarsh on December 5, 1777, and walked many miles in the snow to warn Washington -- is apparently a much dressed-up version of what happened. The whole Darragh family was engaged in regular spying, and the evidence is that Lydia's brother William was the one who was the messenger. He apparently carried messages under the cloth covering of the buttons on his coat.

.jpg)

|

| Joseph Galloway |

Two types of spying have a greater ring of authenticity. The British needed pilots to guide their ships up the Delaware past fortifications and obstacles. Maps were nice, but it seemed simpler to enlist the efforts of two ladies of easy virtue, Ms. O'Brien and Ms. McCoy, to hang out in taverns and entice local ship pilots to enlist to guide the British ships into Philadelphia. The British spymasters even had the ingenuity to entice a member of the Continental Congress, Joseph Galloway, to turn over the commentary records from which troop strength could be estimated from the food consumed. It is not recorded whether suitable adjustments were made for starving troops, stolen supplies, or fraudulent charges, however.

|

| Benedict Arnold |

Two prominent officials were accused of selling out the side, but an accusation of this sort is easily made, hard to prove. When the examples of Benedict Arnold and Peggy Chew can be verified, however, there is always doubt cast on everyone which some will believe. The system of double signatures was used, so there were two co-treasurers of the United States, Joseph Hellegas and George Clymer. Letters have been produced indicating that one or the other sold the commissary records. Hellegas' home is still today the residence outside Pottstown of a prominent Philadelphia surgeon, and his portrait appears on the ten-dollar bill. In so doing, he started a tradition of Secretaries of the Treasury on the ten-dollar bill, presently occupied by Alexander Hamilton. George Clymer, for his part, was a signer of the Constitution and a favorite of George Washington. Are these stories true? Who knows, but in an eight-year war, John Nagy has accumulated evidence that there were over five hundred documented spies. The essential question remains one of whether to believe the documents.

The King's Road

|

| Plays and Players of Haddonfield |

Harry Kaufman may not have started the Plays and Players of Haddonfield, but he certainly sparked it to a near-professional level in a town of 7000 people. The orchestra and the ballet company are particularly outstanding at the moment, the soloists on the stage quite good, although they never made the grand European tour which is thought to be the prerequisite for getting into the big time. Harry was the life of any party, and particularly good at composing little ditties, never quite getting around to stringing them together into a musical comedy until the 250th anniversary of the town. Even then, it is recalled he was shy and reluctant and had to be pushed a little. Since The King's Road appeared shortly after Oklahoma! transformed, even revolutionized, American musical comedy, it was not only the model but the stimulus for a similar comedy celebrating the beginnings of our little state. The plot was a simple one of a conflicted love affair. The striking innovation of Oklahoma! was to crowd most of the show's songs into the first act, repeating snatches of their themes as sort of Wagnerian background commentary throughout the remainder of the play. The other innovation of what was originally called Green Grow the Lilacs was the addition of Agnes DeMille's ballet company to emphasize the real historical theme with light-hearted music. Since I was one of the original reviewers for Oklahoma! in its New Haven tryouts, I can remember the revolutionary impact of that play, very well.

|

| Anthony Wayne |

Harry had to go to the Historical Society for authentic details of the conflict between the attraction for Revolutionary aspirations for Liberty, and loyalty to the earlier sufferings of Quakers for their pacifist leanings. Some Quakers deserted their faith to join the Revolution, and other Quakers tried to convert the Hessian soldiers. And still, others were loyal to the King of England. The Revolution was almost won at this moment, as the British occupants of Philadelphia had abandoned their supplies to attack, and had to get to the British fleet, bottled up in the lower Delaware River by fortifications at Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer on the Jersey side of the river. The Hessians had been sent to attack Fort Mercer from the rear, passing through Haddonfield and stopping one night before going on to what we now call National Park. While the Hessian officers were being entertained by John Gill with discussions of the futility of war, Jonas Cattell slipped out of town and ran to alert Fort Mercer of its danger. The guns of the Fort were turned around, and the defenders pretended not to notice the approach of the Hessians until they were ambushed and largely destroyed. If Fort Mifflin on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River could have held out, the starving British might have had to surrender, but that didn't happen. In any event, the New Jersey Militia did its part, and little Quaker Haddonfield helped them in a sort of characteristic Quaker way. With a ratta-tat-tat and a fiddly dee, the rag-tag swallow-tail Jersey Militia got all the credit.

The play does not emphasize that the State of New Jersey was founded at the Indian King Tavern during these commotions, or that General Washington starving at Valley Forge sent Mad Anthony Wayne to circle up and around Trenton to drive a herd of cattle back from Salem County, two hundred miles back to Valley Forge. The British sent Captain Simcoe down to Salem County to massacre the Quaker farmers who provided the cattle. These later developments are only mentioned in its anthem to "Generals Wayne, LaFayette, and Pulaski", and every good resident of Southern New Jersey is supposed to know what that is all about.

The Quaker historian Rufus Jones established the enduring tradition that this split is what ultimately reduced the Quakers from the dominant religious group to a small religious sect in the three states once owned by William Penn, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. Related to such turmoil was the claim that more battles of the Revolution were fought in New Jersey than in any other state; if you include the large privateer navy going to see from the Jersey Pine Barrens, that is probably true. And every twenty-five years or so, we have to put on a revival of "The King's Road", and just show 'em.

Free Quaker Meetinghouse

|

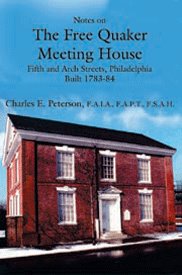

| Independence Hall |

Until this year, there was a Beautiful Mall stretching north from the State House (Independence Hall) to the approaches of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Concealing an enormous parking garage underneath it, the surface looked like a several-block lawn lined with flowering trees in the spring, framing the beautiful Eighteenth Century building (just as the mall in Washington leads up to the Washington Monument.)

Stretching from Independence Hall east to the Delaware River is another mall filled with historical buildings like Carpenters Hall , the First Bank(Girard's) and Second Bank (Biddle's), the Old and the New Custom houses, the American Philosophical Society, and others. The eastern mall was the property of the State of Pennsylvania when it was created, but it soon seemed more economical to the frugal rural legislature to turn it over to the federally funded National Park Service, joining the mall stretching northward. Well, somebody got another ton of federal money appropriated, and now we are filling the north mall with buildings which largely hide Independence Hall from the passersby. With just a few more Congressional earmarks, the imposing beauty of the mall will be submerged, but it hasn't quite reached that point yet. There is a perfectly enormous New Visitors Center, containing a couple of auditoriums and a big bookstore. Mostly the concept seems to be to provide a place to get out of the rain if you are an out of town visitor, provide public bathrooms, and a place to get a hot dog. At least the visitors center is red brick, and arched, with white woodwork. At the far northern end is an overwhelming stark granite block of a building, which will open July 4, 2003. It is a Constitution Center, claimed to be an interactive museum, and we shall see what we shall see. The looming monolith overwhelms and blocks the view to Independence Hall, and it better be good, when the insides get finished.

|

| Free Quaker Meeting |

If Independence Hall, which after all is a block long, is overwhelmed by the new constructions, the Free Quaker Meeting is totally hidden. This perfectly charming Eighteenths Century Quaker meetinghouse is just across Fifth Street from Benjamin Franklin's Grave, and just across Arch Street from the Constitution thing, completely in its shadow. Charles E. Peterson designed the restoration of the building, which had been added to and detracted from, over the years, but you can be sure its interior is now both beautiful and authentic. Before you go in, notice the inscription on the plaque under the northern eaves:

By General Subscription for the FREE QUAKERS. Erected in the Year of OUR LORD 1783 and of the EMPIRE 8.

The Quakers who built this building seem to have thought they were part of a new empire, but that implies an emperor, and of course, one was never created. Three years after the dedication of this building the Constitutional Convention met in the same Independence Hall, and our national form of government was somewhat strengthened from the Articles of Confederation also written here. Benjamin Franklin had a hand in both documents, but the first one was mainly composed by John Dickinson, and the second one by James Madison. If you go into the Free Quaker building, it seems to be a single large room with an interior balcony, and a couple of small staircases in the back leading down to what would presumably be restrooms. As a matter of fact, the Park Service extended the basement to include kitchen and dining room, and several offices for themselves which are a surprise if you are allowed to go down to see them.

|

| History of Free Quakers |

Charlie Peterson wrote a book about the restoration, but the main book about the spiritual history of this group was written by Charles Wetherill. Quakers, as everyone ought to know, are pacifists. The American Revolution put a number of them in a quandary because they agreed that Great Britain was injuring their rights by denying them a representative in the Parliament which ruled them but resorting to violence was another matter entirely. Eventually, a group did break away from the main Quaker church to fight for independence. They were prompt "readout of the meeting", the equivalent of being excommunicated, not allowed to worship in the regular meeting houses they had helped finance or to be buried in the church graveyards. Samuel Wetherill was one of the leaders of this group, just as his descendants are the most active today in the surviving historical society. Samuel created quite a furor, demanding to use the Orthodox meeting house and burial grounds. He was, in his own view, just as much a Quaker as the others since no doctrine is absolutely fixed in that religion, and was freely entitled to speak his mind to persuade others of the rightness of his sincere positions. The main body of Quakers would have none of it, and the Free Quakers were firmly expelled, forced to hold a public subscription and build their own meeting house. Wetherill of course personally knew every one of the members who expelled him, and there may be some truth to his loud, pointed and unchallenged contention that the true division was not between pacifists and fighters, but between Tories and advocates of Independence. Whatever the truth of these accusations, it does seem in retrospect that the split was fairly divided between wealthy established merchants, and small shopkeepers and artisans. Quite a few now-famous names appear on the rolls of the Free Quakers, like Timothy Matlack the actual Scribe of the Declaration of Independence document, Biddles, Lippincott, John Bartram,Crispins, Kembles, Trippes, and Wetherills. When the meeting had dwindled down in 1830 to two lone parishioners, one was a Wetherill, and the other was Betsy Ross, herself.

A comment is submitted by a reader:

I think your description of the Free Quakers oversimplifies their origins. It is true that Samuel Wetherill was disowned by Friends for his military activities. However, other Free Quaker leaders were bounced -- often years before the Revolution -- for other reasons. Timothy Matlack, for not paying his debts. Betsy Ross, for an improper marriage. Christopher Marshall, for counterfeiting. I haven't traced everyone listed as a member in the (1907?) Stackhouse history of the Free Quakers. But I did search in Quaker records for perhaps a dozen and found no records that people with those names had ever been Quakers. I think it would be more accurate to say of the Free Quakers that the Revolution drew together people of many different types and that when some of those people had things in common -- such as Quaker background -- they united around those things. (Posted by Mark E. Dixon )

Betsy Ross on Hard Times

|

| Betsy Ross |

Maria Thompson, the noted historian of Philadelphia's Independence Square area and matters related, recently reported to the annual meeting of the Free Quakers that there was apparently an unrecognized feature to the later years of Betsy Ross. Betsy was one of the two surviving members of the Free Quaker Meeting at the time it was inactivated in the Nineteenth Century.

When the meeting was "laid down", it naturally had to define a purpose for the funds and assets of the inactive church, and one purpose was to care for the poor. According to the records, the first recipient of such charity was Betsy Ross. Anyone who knows anything about Quakers would be pretty sure there was nothing irregular about this. Money designated for indigents would positively be used for indigents. So this little scrap of information is really just a sad little footnote to her personal history.

REFERENCES

| Betsy Ross and the Making of America Marla R. Miller ISBN: 0805082972 | Amazon |

Inazo Nitobe, Quaker Samurai

|

| Inazo Nitobe |

The story of Inazo Nitobe (1862-1933) comes in two forms, one from the Philadelphia Quaker community, and the other from his home, in Japan. One day in Philadelphia, a well-known ninety-year-old Quaker gentleman, rumpled black suit, very soft voice -- and all -- happened to remark that his Aunt had married a Samurai. A real one? Topknot, kimono, long curved sword, and all? Yup. Uh-huh.

That would have been Inazo Nitobe, who met and married Moriko, nee Elizabeth Elkinton, while in college in Philadelphia. He became a Quaker, and when the couple returned to Japan, the Emperor then found himself confronted with a warrior nobleman who was a pacifist. You can next perceive the hand of his Quaker wife in the deferential diplomatic suggestion that there were vacancies for Japan at the League of Nations and the Peace Palace in the Hague. Perhaps, well perhaps, there could be service to his Emperor as well as his new religion in such an appointment for her new husband. Good thinking, let it be done. As far as Philadelphia is concerned, Ambassador Nitobe next appeared when Japan was invading Manchuria. The Emperor had sent Nitobe on a tour of America to explain things. At the meetinghouse then on Twelfth Street, Nitobe adopted the line that Japan was only bringing peace and order to a chaotic barbarian situation, actually saving many lives and restoring quiet. After a minute of silence, Rufus Jones rose from his seat on the "facing bench": He was having none of it. And that was that for Nitobe in Philadelphia.

The other side of this story quickly appears if you go to Japan and ask some acquaintances if they happen to have heard the name Inazo Nitobe. That turns out to be equivalent to asking some random American if he has ever heard of Abraham Lincoln. To begin with, Nitobe's picture appears on the 5000 Yen ($50) bills in everybody's pocket. He was the founder of the University of Tokyo, admission to which now is an automatic ticket to Japanese success. He wrote a number of books that are now required reading for any educated Japanese. A number of museums, hospitals, and gardens are named after him; one of them outside Vancouver, at the University of British Columbia.

Nitobe's father, Jujiro Nitobe, had been the best friend of the last Shogun, deposed by the return of the Emperor to effective control after Perry opened up Japan to Western ideas. The Shogun was beheaded, of course, and the tradition was that the victim could ask his best friend to do the job because he would do it swiftly. Jujiro was unable to bring himself to the task, refused, and his family was accordingly reduced to poverty. Subsequently, the Samurai were disbanded by the newly empowered Emperor, given a pension, and told to look for peaceful work. Inazo Nitobe was in law school when the Emperor's emissary came and said that Japan did not need culture, it had plenty of culture. The law students would please go to engineering school, where they could help Japan westernize.

Nitobe later wrote a perfectly charming memoir, called Reminiscences of Childhood in the Early days of Modern Japan , which dramatizes in just a few pages just how wide the cultural gap was. For example, Nitobe's father brought home a spoon one day, and this curious memento of how Westerners eat was placed in a position of high honor. One day, a neighbor ordered a suit of western clothes, and hobbled around it, saying he did not understand how Westerners are able to walk in such clothes. He had the pants on backward.

One of Nitobe's greatest achievements was to struggle with his appointment as Governor of Formosa (Taiwan). Japan acquired this primitive island in 1895, and Nitobe got the uncomfortable role of colonist in Japan's first experience with colonization. He sincerely believed it was possible for Japan to bring the benefits of Westernization to another Asian backwater, but just as the British found in their colonies, there was precious little gratitude for it. Although he was undoubtedly acting dutifully on the Emperor's orders when he later came to Twelfth Street Meeting, he surely knew -- perhaps even better than Rufus Jones -- that there was something to be said on both sides, no matter how conflicted you had to be if you were in a position of responsibility. This most revered man in his whole nation almost surely saw he had been a complete failure in Philadelphia.

George Willoughby, 95, Peace Activist

|

| George Willoughby |

Age was nothing but a number for 95-year-old peace activist George Willoughby of Deptford. His worldwide antiwar protests and nonviolent teachings started when he was in his mid-40s and continued until just weeks ago.

Mr. Willoughby was planning a six-week trip this month to India to meet friends he had made during visits to the birthplace of his idol, Mohandas K. Gandhi, and probably to give some of his trademark peace talks.

But Mr. Willoughby died at home of heart failure Jan. 5, a month short of the journey.

A Quaker who led local protests and famous treks from San Francisco to Moscow and from New Delhi to Beijing, Mr. Willoughby recruited many advocates for nonviolent conflict resolution, said a friend and member of the Central Philadelphia Meeting, Nicole Hackel.

"Once you experienced him, you didn't forget him," Hackel said, adding that she became a Quaker in the 1970s because of Mr. Willoughby's influence. "George would engage in conversation with anyone, even a 5-year-old who was attending a meeting for the first time."

Mr. Willoughby became a household name for area Quakers after he became director of the Central Committee of Conscientious Objectors in Philadelphia in 1954. He soon was a frequent presence in the news, mostly under headlines with the words peace, marchers, and protest.

In 1958, Mr. Willoughby was one of five crewmen on the sailboat Golden Rule who received 60-day jail sentences in Honolulu for trying to sail to the area of the Pacific Ocean where the U.S. government was testing nuclear bombs in the atmosphere.

That was Mr. Willoughby's first of many incarcerations, said his son, Alan.

"The Society of Friends in Honolulu brought him a lot of decent food. . . . He always spoke highly" of the Hawaii jail experience, his son said with a slight laugh.

Two years later, Mr. Willoughby organized a dual-continent march to protest nuclear testing. Protesters in groups of about a dozen each covered six countries in 10 months between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Mr. Willoughby joined the group in Poland. Soviet officials stopped them 100 yards short of the Lenin-Stalin tomb in Moscow's main square, according to reports at the time. Instead of delivering speeches, the group was forced to stand in the square in a silent vigil.

In 1963, Mr. Willoughby embarked with about a dozen others on what he intended to be his longest hike - 4,000 miles from New Delhi to Beijing to promote peace between India and China.

Before his journey, a Philadelphia Evening Bulletin reporter asked whether there was a better way than marching to bring about peace.

Mr. Willoughby responded: "Most people of these countries walk; we can reach them. Even if it does no good at all, it is worth it. It's an idea I believe in, and if it produces fruit, so much the better."

After eight months of walking, Mr. Willoughby and company were stopped at the India-China border and barred from crossing into China.

In the next three decades, Mr. Willoughby's projects included the formation of A Quaker Action Group, which opposed the Vietnam War, in 1966; the Life Center Community in West Philadelphia, a training and campaign center for nonviolence, in 1971; and Peace Brigades International, a human-rights group, in 1981.

One of his most memorable contributions to South Jersey, family and friends said, was the creation of the Old Pine Farm Natural Lands Trust, 45 acres of natural conservancy in Deptford.

In his later years, Mr. Willoughby received honors around the world for his peace work, such as the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation award in 2002 in Mumbai, India, which recognizes those who promote Gandhi's ideas and values.

Born in Cheyenne, Wyo., Mr. Willoughby spent much of his childhood in the Panama Canal Zone, where his father worked in construction.

Mr. Willoughby was part of his high school's JROTC program, but, according to friend and biographer Gregory Barnes, he quickly realized the military was not for him.

A family rift led Mr. Willoughby to live in Des Moines, Iowa, with a family friend, Elinor Robson. In the 1930s, he received three degrees in political science, including a doctorate from the University of Iowa.

In 1940, Mr. Willoughby married Lillian Pemberton, a "birthright Quaker" he met in college. By 1944, he became a Quaker, fully immersed in the Religious Society of Friends' beliefs and ideologies.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Mr. Willoughby worked for the Des Moines office of the American Friends Service Committee before moving to Philadelphia with his wife and their four children.

After bypass surgery in 2000, Mr. Willoughby had to slow down. He wasn't able to participate in as many marches and rallies as he would have liked, his son said, but he remained active online.

One of Mr. Willoughby's last protests was in March 2003, an organized obstruction of the entrance of a federal building in Philadelphia to protest the war in Iraq. He took photos of his 89-year-old wife getting her head shaved as part of the demonstration.

"I've never seen her like that, but I like it," he told a reporter. Lillian Willoughby died last year.

One of Mr. Willoughby's last speeches was at Scattergood Friends School in Iowa a few months after his wife's death. He took a road trip with Hackel and one of his daughters to the Scattergood refuge camp's 70th-anniversary reunion, which was held at the school.

Once there, Mr. Willoughby did what he did best: talk. "He just fascinated the young people there," Hackel said.

Some of Mr. Willoughby's last words of advice were: "It is the duty of the opposition to oppose," his son said. "He thought it is your duty to speak up . . . for what you believe is right."

In addition to his son, Mr. Willoughby is survived by daughters Sally, Anita, and Sharon and three grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. Saturday at the Friends Center at 15th and Cherry Street

Marian B. Sanders, Quaker Activist, 87

|

| Pre K Group |

Marian Binford Sanders, 87, of Mount Airy, a former principal of Lansdowne Friends School who devoted her life to Quaker service, died following gallbladder surgery April 23 at Chestnut Hill Hospital

Mrs. Sanders headed Lansdowne Friends from 1975 to 1981. During that time, her husband, Edwin, was a director of Pendle Hill, a Quaker study center in Wallingford, where the couple lived and where she taught courses. In the early 1980s, the couple lived at Cambridge Friends Meeting in Massachusetts, where they ministered and supervised the facilities.

|

| Chestnut Hill |

After retiring to Chestnut Hill in 1985, according to her son, David, Mrs. Sanders lectured on the poet William Blake at Pendle Hill, taught adult literacy, and cared for her husband, who had Alzheimer's disease, until his death in 1995.

She was dedicated to the concept of world citizenship, her son said and opened her home to students and travelers from around the world. In 1997, she received an award from Earlham college in Indiana honoring her and her late husband for the "55 years of the shared struggle for human justice, for an end to war ... and for broad service in the Society of Friends."

Mrs. Sanders grew up in Dayton, Ohio, and Butler, Pa. She earned a bachelor's degree from Earlham College and, in 1939, the year she married, a master's degree in English literature from Pennsylvania State University.

In 1940, her husband, a Quaker pacifist, was sentenced to federal prison for a year for refusing to register for the draft. After he was paroled, the couple taught at Pacific Ackworth Friends School in Temple City, Calif., which they helped found. For more than a year in the 1960s, they trained teachers in Kenya. Later, Mrs. Sanders taught English literature in Russia as an exchange teacher with the American Friends Service Committee.

In addition to her son, David, she is survived by sons Michael, Richard, John, Robert, and Erin; a daughter, Beth Sanders-Blevins; eight grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

A memorial service will be at 3 P.M. June 26 at Pendle Hill 338 Plush Mill Rd., Wallingford.

Memorial donations may be made to Lansdowne Friends School, 110 N. Lansdowne Ave. Lansdowne, Pa. 19050.

-Philadelphia Inquirer, May 15, 2004

9 Blogs

Quakers Turn Their Backs on Power

During the French and Indian War, the Quakers who ruled Pennsylvania were forced to choose between political power and peaceful principles. They withdrew from power.

Pembertons

One of the oldest, most prominent Quaker families contained a multitude of famous, rich, distinguished leaders. Many suffered imprisonment or exile for their pacifism, but one Pemberton is the highest-ranking wartime general buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery. He was a Confederate.

One of the oldest, most prominent Quaker families contained a multitude of famous, rich, distinguished leaders. Many suffered imprisonment or exile for their pacifism, but one Pemberton is the highest-ranking wartime general buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery. He was a Confederate.

Espionage in the Revolution

Almost everyone in the American Revolution could speak English, so it is not surprising to hear of many spies.

Almost everyone in the American Revolution could speak English, so it is not surprising to hear of many spies.

The King's Road

It's only been performed fifteen or twenty times, but Hayyr Kaufman's musical comedy captures the real spirit of Olde Haddonfield.

It's only been performed fifteen or twenty times, but Hayyr Kaufman's musical comedy captures the real spirit of Olde Haddonfield.

Free Quaker Meetinghouse

It's only open a few days each year, but the red brick building at 5th and Arch was the meeting house for those few Quakers, including Betsy Ross, who fought for the Revolution. The Park Service has made a beautiful restoration, which deserves to be seen by more people.

It's only open a few days each year, but the red brick building at 5th and Arch was the meeting house for those few Quakers, including Betsy Ross, who fought for the Revolution. The Park Service has made a beautiful restoration, which deserves to be seen by more people.

Betsy Ross on Hard Times

The famous Revolutionary seamstress lived long into the 19th Century, apparently outliving her savings. A useful tale, perhaps, for Social Security reform.

The famous Revolutionary seamstress lived long into the 19th Century, apparently outliving her savings. A useful tale, perhaps, for Social Security reform.

Inazo Nitobe, Quaker Samurai

One of the most revered leaders of modern Japan was a converted Samurai, married to a Philadelphia Quaker. His father was an advisor to the Emperor, a family of famous warriors.

One of the most revered leaders of modern Japan was a converted Samurai, married to a Philadelphia Quaker. His father was an advisor to the Emperor, a family of famous warriors.

George Willoughby, 95, Peace Activist

In The Philadelphia Inquirer for February 4, 2010, By Claudia Vargas Inquirer Writer.

In The Philadelphia Inquirer for February 4, 2010, By Claudia Vargas Inquirer Writer.

Marian B. Sanders, Quaker Activist, 87