3 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

Slavery and Quakerism

Quakers wanted to free their own slaves peacefully; Bostonians wanted to abolish slavery, punish slaveholders.

Jury Nullification

|

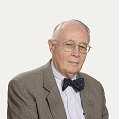

| Tom Monteverde |

We must be grateful to the late distinguished litigator, Tom Monteverde, for reminding us of the importance of the jury in American history. Juries seldom realize how much power they can have if they unite on a common purpose. In fact, juries have the implicit right to veto almost anything the rest of government does, by rendering it unenforceable. If the jury opinion is a majority view, nothing but a civil war can legally stop them. So it helped Washington to have jury nullification seem an invincible Quaker idea, while the South trusted a rich slave-owner who had renounced power.

|

| William Penn |

The right to a jury trial originated in the Magna Carta in 1215, but a jury's essentially unlimited power was established four centuries later by Quakers. The legal revolution grew out of the 1670 Hay-market case, where the defendant was William Penn, himself. Penn was accused of the awesome crime of preaching Quakerism to an unlawful assembly, and while he freely admitted his guilt he challenged the righteousness of such a law. The jury refused to convict him. The judge thus faced a defendant who said he was guilty and a jury who said he wasn't. So, the exasperated judge responded -- by putting the jury in jail without food.

The juror Edward Bushell appealed to the Court of Common Pleas, where the problem took on a new dimension. The Justices certainly didn't want juries flouting the law, but nevertheless couldn't condone a jury being punished for its verdict. Chief Justice Vaughn decided that intimidating a jury was worse than extending its powers, so the verdict of Not Guilty was upheld, and Penn was set free. Essentially, Vaughn agreed that any jury that wasn't allowed to acquit was not really a jury. In this way, the legal principle of Jury Nullification of a Law was created. A verdict of not guilty couldn't make William Penn innocent, because he pleaded guilty. A verdict of not guilty, under these circumstances, meant the law had been rejected. Jury nullification thus got to be part of English Common Law, hence ultimately part of the American judicial system.

|

| Andrew Hamilton |

This piece of common law was a pointed restatement of just who was entitled to make laws in a nation, whether or not nominally it was ruled by a king or a congress. Repeated British evasion of the principles of jury trial became an important reason the American colonists eventually went to war for independence, and probably a better one than some others. The 1735 trial of Peter Zenger was an instance where Andrew Hamilton, the original "Philadelphia Lawyer", convinced a jury that British law, blocking newspapers from criticizing public officials for improper conduct, was too outrageous to deserve enforcement in their court. In that case, jury defiance became even more likely when the judge instructed the annoyed jury that "the truth is no defense". Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette was here quick to come to the side of jury nullification, saying, "If it is not the law, it ought to be law, and will always be law wherever justice prevails." Franklin quickly became allied with Andrew Hamilton, who became Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly.

|

| John Hancock |

The Zenger case was often stated to be the origin of the Freedom of the Press in our Constitution fifty years later, but in fact the First Amendment merely provides that Congress shall pass no laws like that. Hamilton had persuaded the Zenger jury they already had the power to stop enforcement of such tyranny, and the First Amendment could be seen as trying to prevent enactment of laws that will foreseeably incite a jury to revolt.

The Navigation Acts of the British government, for example, were predictably offensive to the American colonists, whose randomly chosen representatives on juries were then rendered useless with their wide-spread refusal to convict. This, in turn, provoked the British ministry. John Adams made a particularly famous defense of John Hancock who was being punished with confiscation of his ship and a fine of triple the cargo's value. Adams was later singled out as the only named American rebel the British refused to exempt from hanging if they caught him. As everyone knows, Hancock was the first to step up and sign the Declaration of Independence, because by 1776 there was widespread colonial outrage over the British strategy of transferring cases to the (non-jury) Admiralty Court. Many colonists who privately regarded Hancock as a smuggler were roused to rebellion by the British government thus denying a defendant his right to a jury trial, especially by a jury almost certain not to convict him. To taxation without representation was added the obscenity of enforcement without due process. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the newly created United States, ruled in 1794 that "The Jury has the right to determine the law as well as the facts." And Thomas Jefferson built a whole political party on the right of common people to overturn their government, somewhat softening, it is true, when he grasped where the French Revolution was heading. Jury Nullification then lay fairly dormant for fifty years. But since the founding of the Republic and the reputation of many of the most prominent founders was based on it, there was scarcely need for any emphasis.

|

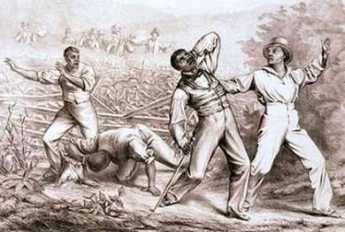

| Slave |

And then, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 began to sink in. It became evident that juries in the Northern states would routinely refuse to convict anyone under that law, or under the Dred Scott decision, or any other similar mandate of any branch of government. In effect, Northern juries threw down the gauntlet that if you wanted to preserve the right of trial by jury, you had better stop prosecuting those who flouted the Fugitive Slave law. In even broader terms, if you want to preserve a national government, you had better be cautious about strong-arming any impassioned local consensus. A rough translation of that in detail was that no filibuster, no log-rolling, no compromises, no oratory, no threats or other maneuvers in Congress were going to compel Northern juries to enforce slavery within their boundaries of control. All statutes lose some of their majesties when the congressional voting process is intensely examined, and public scrutiny of this law's passage had been particularly searching. Even if Southern congressmen would be successful in passing such laws, it wasn't going to have any effect around here. The leaders of Southern states quickly got a related message, and their own translation of it was, "We have got to declare our independence from this system of government that won't enforce its own laws". If juries can nullify, then states can nullify, and the national union was coming to an end. Both sides disagreed so strongly on this one issue they were willing, for the second time, to risk war for it.

Ku Klux Klan

The idea should be resisted that Jury Nullification is always a good thing. After the Civil War, many of the activities of the Ku Klux Klan were tolerated by sympathetic juries. Many lynch mobs of the Wild, Wild West were encouraged in the name of law and order. Prohibition of alcohol by the Volstead Act was imposed on one part of society by another, and Jury Nullification effectively endorsed rum-running, racketeering, and organized crime. The use of marijuana and abortion are two further examples where disagreement is so strong that compromise eludes us. What is at stake here is protecting the rights of a minority, within a society run by a majority. If minority belief is strong enough, jury nullification issues an unmistakable proclamation: "To proceed farther, means War."

|

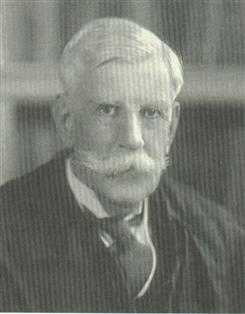

| Oliver Wendell Holmes |

That's a somewhat strange outcome for a process started by pacifist Quakers, so the search goes on for a better idea. Distinguished jurists differ on whether to leave things as they are. In a famous exchange, Oliver Wendell Holmes once had dinner with Judge Learned Hand, who on parting extended a lawyer jocularity, "Do justice, Sir, do justice." To which, Holmes then made the somewhat surly response, "That is not my job. My job is to apply the law."

Thus lacking any better approach, it is hard to blame the US Supreme Court for deciding this was something best left unmentioned any more than absolutely necessary. The signal which Justice Harlan gave in the majority opinion on the 1895 Sparf case was the very narrow ruling that a case may not be appealed, solely on the basis that the trial jury was not informed of its right to nullify the law in question. Encouraged by this vague hint, what has evolved has been a growing requirement that incoming jurors take an oath "to uphold the law", officers of the court (ie lawyers)are discouraged from informing a jury of its true power to nullify laws, and Judges are required to inform the jury in their charge that they are to "take the law as the judge lays it down" (ie leave appeals to higher courts). If a jury feels so strongly that it then persists in spite of those restraints, well, you apparently can't stop them. Nobody thinks this is a perfect solution, and aggrieved defendants like the Vietnam War protesters are quite vocal in their belief that the U.S. Supreme Court finally emerged with a visibly asinine principle: a jury does indeed have the right to nullify, but only as long as that jury is unaware it has that right. That's almost an open invitation to perjury if accurate; but while it's not precisely accurate, it comes close to being substantially true.

That's where matters stand, and apparently will stand, until someone finds better arguments than those of Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Andrew Hamilton -- and William Penn.

Slavery: If This be done well, What is done evil?

|

| Francis Daniel Pastorius |

The Declaration of the German Friends of Germantown, Against Slavery, in 1688.

These are the reasons why we are against the traffic of men's body, as followeth:

Is there any that would be done or handled in this manner? viz.: to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life? How fearful and faint-hearted are many at sea, when they see a stranger vessel, being afraid it should be a Turk, and they should be taken, and sold for slaves in Turkey. Now, what is this better done, than Turks do? Yea, rather it is worse for them, which say they are Christians; for we hear that the most part of such negers is brought hither against their will and consent and that many of them are stolen. Now though they are black, we cannot conceive there is more liberty to have them, slaves, as [than] it is to have other white ones. There is a saying , that we shall do to all men like as we will be done [to] ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent, or color they are. And those who steal or rob men, and those who purchase them, are they not all alike? Here is liberty of conscience, which is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of the body, except evil-doers, which is another case. But to bring men hither, or to rob, [steal] and sell them against their will, we stand against. In Europe, there are many oppressed for conscience sake; and here there are those oppressed which are of black color. And we who know others, separating wives from their husbands, and giving them to others: and some sell the children of these poor creatures to other men. Ah! do consider well this thing, you who do it, if you would be done in this manner--and if it is done according to Christianity! You surpass Holland and Germany in this thing. This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe when they hear of [it,] that the Quakers do here handler men as they handle there the cattle. And for that reason, some have no mind or inclination to come hither. And who shall maintain this your cause, or plead for it? Truly, we cannot do so, except you shall inform us better hereof, viz,: That Christians have liberty to practice these things, Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse, towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating husbands from their wives and children. Being now this is not done in the manner we would be done at, [by]; therefore, we contradict [oppose], and are against this traffic of men's body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid purchasing such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing, if possible. And such men ought to be delivered out of the hands of the robbers, and set free as in Europe. Then is Pennsylvania to have a good report, instead, it hath now a bad one, for this sake, in other countries. Especially whereas the Europeans are desirous to know in what manner the Quakers do rule in their province; and most of them do look upon us with an envious eye. But if this is done well, what shall we say is done evil?

If once these slaves ( which they say are so wicked and stubborn men,) should join themselves--fight for their freedom, and handle their masters and mistresses, as they did handle them before; will these masters and mistresses take the sword at hand and war against these poor slaves, like, as we are able to believe, some will not refuse to do? Or, have these poor negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?

Now consider well this thing, if it is good or bad. And in case you find it to be good to handle these blacks in that manner, we desire and require you hereby lovingly, that may inform us herein, which at this time never was done, viz., that Christians have such a liberty to do so. To this end, we shall be satisfied on this point, and satisfy likewise our good friends and acquaintances in our native country, to whom it is a terror, or fearful thing, that men should be handled so in Pennsylvania.

This is from our meeting at Germantown, held ye 18th of the 2nd month, 1668, to be delivered to the monthly meeting at Richard Worrell's.

Garret Henderich

Derick op de Graeff

Francis Daniel Pastorius

Abram op de Graeff.***

At our Monthly meeting, at Dublin, ye 30th 2d mo., 1688, we have inspected ye matter, above mentioned, and considered of it, we find it so weighty that we think it not expedient for us to meddle with it here, but do rather commit it to ye consideration of ye quarterly meeting; ye tenor of it is related to ye truth.On behalf of ye monthly meeting,

Jo. Hart.

***

This above mentioned was read in our quarterly meeting, at Philadelphia, the 4th of ye 4th mo., '88, and was from thence recommended to the yearly meeting, and the above said Derick, and the other two mentioned therein, to present the same to ye above said meetings, it is a thing of too great a weight for this meeting to determine.Signed by order of ye meeting.

Anthony Morris

Differences of Quaker Opinion

A reader of Philadelphia Reflections feels that a balanced appraisal of the slavery issue should include mention of the Quakers who were determined in their opposition to abolition. After all, it took eighty years for the original concern of the Germantown meeting to be fully adopted by the Philadelphia Yearly meeting as a formal minute under the prodding of John Woolman. Since the minute gives permission for particularly concerned Friends to go speak with slave-holding Quakers, it is clear that even some Philadelphia Quakers held slaves and were reluctant to release them.

| ||

| Abraham Redwood 1709-1788 |

Newport, Rhode Island, was an even more awkward case. In colonial times, and even today to some degree, individual Yearly meetings were cordial, but under no formal obligation to respond to each other's decisions. The English seaport of Bristol had developed a sugar trade with the West Indies, and a number of Bristol Quakers moved to Newport. Acquiring very large sugar plantations in the Indies, they shipped molasses to rum distilleries in Newport or else directly back to Bristol where a candy industry had been established. The next step was the shipment of rum and/or trading trinkets to Africa, to be exchanged for slaves, who were taken to the Caribbean and exchanged for a cargo of molasses. Molasses then went to Newport, in a triangular trade pattern which admittedly avoided bringing slave cargo to Rhode Island, but whose principal purpose was taking advantage of the prevailing Atlantic trade winds while maintaining a full cargo over the whole distance. The largest partnership in this trade belonged to four Newport Quakers, one of whom was Abraham Redwood.

Redwood owned 230 slaves in Antigua and was among the richest men in America at the time. It is rather troubling to learn that the average "turnover" of slaves on Antigua was seven years, and that slave rebellions were fairly common. Redwood donated five hundred pounds to the Newport Philosophical Society for the purchase of 1300 books, thereby establishing the Redwood Library in 1747, one of the oldest in the country, although the Library Company of Philadelphia was established in 1731. By almost any standard, Redwood was nevertheless a "weighty" Quaker. When he resolutely refused to sell his slaves, he was "read out" of the meeting.

Details of the discussions which were conducted are no longer readily available, but it is obvious that collision of these two equally stubborn viewpoints was particularly awkward when it led to the banishment of the main employer of the town, and its most important local benefactor. Furthermore, those who worked harmlessly in the rum industry in Newport, or the candy industry in England, were called upon to reflect deeply on the unfortunate slave dealings in which they were, perhaps unknowingly, implicated.

Somehow all of this was accomplished without a total rupture, because thirteen years later Abraham Redwood donated another five hundred pounds to the Quaker Meeting, for the establishment of a school.

Slaveowning Quaker Steps Up To The Plate

|

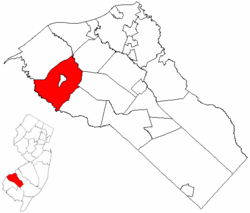

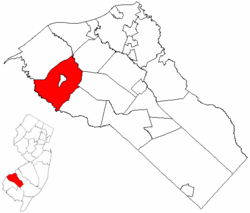

| County of Gloucester |

I, Joseph Nicholson of the Township of Woolwich and County of Gloucester, do hereby set free from bondage my Negro Tenor, aged about twenty-two years, and do, for myself, my Executors and Administrators, release unto the said Tenor, all my Right, and all claim whatsoever as to her person or to any Estate that may acquire, hereby declaring the said Tenor, absolutely free, without any interruption from me, or any person claiming under me.

In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my Hand and Seal this twenty-seventh day of the Twelfth Month, in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy-nine. 1779.

. . . Joseph Nicholson (Seal)

. . Sealed and Delivered in the presence of Joseph Allen

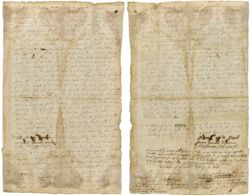

1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery

|

| 1688 Anti-Slavery Petition |

John Woolman Reports on Yearly Meeting, 1758

|

| John Woolman House |

"In this yearly-meeting (1758) several weighty matters were considered; and, toward the last, that in relation to dealing with persons who purchase slaves. . . .

"Many faithful brethren labored with great firmness, and the love of truth, in a good degree, prevailed. Several Friends who had Negro's expressed their desire that a rule might be made to deal with such Friends as offenders who bought slaves in future. To this, it was answered, that the root of this evil would never be effectually struck at until a thorough search was made into the circumstances of such Friends who kept Negro's, with respect to the righteousness of their motives in keeping them, that impartial justice might be administered throughout. Several Friends expressed their desire that a visit might be made to such Friends who kept slaves, and many Friends said that they believed liberty was the Negro's' right; to which, at length, no opposition was made publicly. A minute was made, more full on that subject than any heretofore, and the names of several Friends entered, who were free to join in a visit to such who kept slaves. "

Fanny Kemble Takes the Train South, in 1838

The "Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839" raised strong feelings against slavery, particularly in Frances Anne Kemble's native England. At the outset of her book, Fanny Kemble describes what it was like to travel on American railroads in 1838.

On Friday morning December 21, 1838, we started from Philadelphia, by railroad, for Baltimore. It is a curious fact enough, that half the routes that are traveled in America are either temporary or unfinished -- one reason, among several, for the multitudinous accidents which befall wayfarers. At the very outset of our journey, and within scarce a mile of Philadelphia, we crossed the Schuylkill, over a bridge, one of the principal piers of which is yet incomplete, and the whole building (a covered wooden one, of handsome dimensions) filled with workmen, yet occupied about its construction. But the Americans are impetuous in the way of improvement and have all the impatience of children about the trying of a new thing, often greatly retarding their own progress by hurrying unduly the completion of their works, or using them in a perilous state of incompleteness. Our road lay for a considerable length of time through flat low meadows that skirt the Delaware, which at this season of the year, presented a most dreary aspect. We passed through Wilmington (Delaware) and crossed a small stream called the Brandywine, the scenery along the banks of which is very beautiful. For its historical associations, I refer you to the life of Washington. I cannot say that the aspect of Wilmington, as viewed from the railroad cars, presented any very exquisite points of beauty....

And first, I cannot but think that it would be infinitely more consonant with comfort, convenience, and common sense, if persons obliged to travel during the intense cold of an American winter in the Northern states, were to clothe themselves according to the exigencies of the weather, and so do away with the present deleterious custom of warming close and crowded carriages with sheet iron stoves, heated with anthracite coal. No words can describe the foulness of the atmosphere...Of course, nobody can well sit immediately in the opening of a window when the thermometer is twelve degrees below zero yet this, or suffocation in foul air is the only alternative...

We pursued our way from Wilmington to Havre de Grace on the railroad, and crossed one or two insets from the Chesapeake, of considerable width, upon bridges of a most perilous construction, and which, indeed, have given way once or twice in various parts already. They consist merely of wooden piles driven into the river, across which the iron rails are laid, only just raising the train above the level of the water. To traverse with an immense train, at full steam-speed, one of these creeks, nearly a mile in width, is far from agreeable...At Havre de Grace we crossed the Susquehanna in a steamboat, which cut its way through the ice an inch in thickness with marvelous ease and swiftness and landed us on the other side, where we again entered the railroad carriages to pursue our road.

7 Blogs

Jury Nullification

William Penn demonstrated one of the most incisive legal minds in England by trapping the British courts in what remains a central unresolved dilemma for the law. He was the defendant in his own case. By the South's way of looking at things, it was a pacifist effort to restrain mindless abolitionism. Meanwhile, both sides calculated it would win if the South decided to fight.

William Penn demonstrated one of the most incisive legal minds in England by trapping the British courts in what remains a central unresolved dilemma for the law. He was the defendant in his own case. By the South's way of looking at things, it was a pacifist effort to restrain mindless abolitionism. Meanwhile, both sides calculated it would win if the South decided to fight.

Slavery: If This be done well, What is done evil?

Philadelphia German Quakers were the first to protest the evils of slavery.

Philadelphia German Quakers were the first to protest the evils of slavery.

Differences of Quaker Opinion

Some Quakers refused to go along with the abolition of slavery. That was particularly true in Newport, RI, the North American point of the triangular slave trade.

Some Quakers refused to go along with the abolition of slavery. That was particularly true in Newport, RI, the North American point of the triangular slave trade.

Slaveowning Quaker Steps Up To The Plate

Slaves were valuable property, but it became a Quaker duty to give them their freedom. John Woolman, who started the idea, suggested freeing them in your will.

Slaves were valuable property, but it became a Quaker duty to give them their freedom. John Woolman, who started the idea, suggested freeing them in your will.

1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery

The first official anti-slavery document to be considered by the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1688.

John Woolman Reports on Yearly Meeting, 1758

At a time when the whole world thought slavery was perfectly natural, John Woolman brought the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to declare it must be abolished.

At a time when the whole world thought slavery was perfectly natural, John Woolman brought the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to declare it must be abolished.

Fanny Kemble Takes the Train South, in 1838

One of several important and influential books that Fanny wrote described her trip from the Philadelphia salons to the slave quarters of Georgia. It's well worth reading, even today.

One of several important and influential books that Fanny wrote described her trip from the Philadelphia salons to the slave quarters of Georgia. It's well worth reading, even today.