3 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

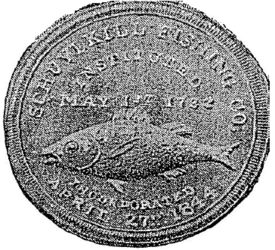

Philadelphia Clubs

New volume 2016-02-16 21:29:48 description

Philadelphia Fish and Fishing

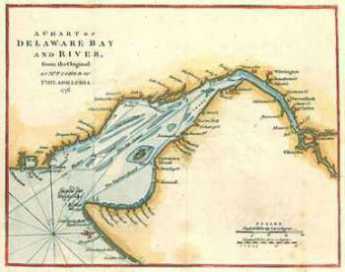

Less than a century ago, Delaware Bay, Delaware River, Schuylkill River, Pennypack Creek, Wissahickon Creek, and dozens of other creeks in this swampy region were teeming with edible fish, oysters and crabs. They may be coming back, cautiously.

Helis the Whale

|

| Beluga Whale |

Helis the beluga whale, male, 12 feet long, said to be 30 years old in a species with a life expectancy of about 35, made an appearance in the upper Delaware River in the spring of 2005. A scar on his back was recognized as having been seen on the St. Lawrence River, where Beluga whales are more commonly observed. Needless to say, there was a local sensation, with crowds of whale-watchers along the banks of the river, sharing binoculars, and buying special whale cookies, t-shirts and the like from opportunistic vendors. Helis arrived April 14, 2005, in time to pay income taxes, go to Trenton, cruising Trenton to Burlington and back, eating shad. Experts saying he is happy as a clam, shad fishermen grumbling a little. Crowds of excited people tried to take snapshots of themselves with Helis in the background.

He stayed with us another week, going back and forth between Burlington and Trenton. Not many other events took place, so the newspapers had front-page stories by Beluga whale experts, sought out for fifteen minutes of fame. Will he come back? How big do Belugas get to be? Frantic calls by reporters obtained the information that Belugas like icy arctic waters, seldom travel alone or this far south. The suggestion was made that Helis may have been banished by the male whales he usually swims with, but others pointed out the unusually good shad run this year and conjectured Helis was an adventurous loner who had discovered a private river of goodies.

|

| Cape May NJ |

We were informed that lots of whales are sighted off Cape May every year; there's a rather large whale sight-seeing industry. Mammals don't breathe the Delaware pollution, but like other mammalian swimmers, they swallow some. So here's a sign that river pollution maybe can't be too bad.

The French Canadians call him "ee-lus" but don't expect that to catch on around here. What's helis mean, anyway? This seems to be the most southern sighting of a Beluga. Reminds us that Kingston New York, a hundred miles up the Hudson, used to be a big whaling port. that Ahab of Melville's Moby Dick was a Quaker, Nantucket variety. Cape May Quakers are related to them more than to Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. After all, Philadelphians are whale-lovers.

Unless someone harpoons Helis, we are all hoping he will bring back lots of his friends next year. Even the shad fishermen recognize that if the whales are searching for shad, there have to be a lot of shad to be attractive. And the whale-memento industry will surely be ready for them.

Shad

Nowadays, we have fresh fruit and vegetables all year Shadround. When produce isn't in season locally, we get it from Florida and California. When even those places are out of season, we bring it in from Chile. But the supermarket and its attendant supply chains are recent phenomena. Before the two World Wars, our food was pretty drab and monotonous during the winter. The first sign of the culinary joys of spring was shad.

|

| Shad |

Everybody loved, which everybody ate in its various forms. Shad was cheap because it was abundant; indeed, it seems difficult for the modern fisherman to imagine the huge quantities of fish that came up the rivers in early March. There was even a special term for fish weighing less than three pounds; at the fish market, such fish were thrown in, free. The term "Bushwacker" referred to the practice of beating the fish in the water to catch them. There once was a time when everybody knew how to use a shad dart, everyone could filet the bones, everyone had fried shad roe for breakfast. Spring, it was acumen in.

Unfortunately, the diversion of fresh water from upper Delaware to New York City, the dumping of waste from the oil refineries near Marcus Hook, and heaven know what other pollution, wiped out the annual shad run. Once a river's shad run is depleted, the main obstacle to getting it revived is the striped bass, who feast on the fingerlings coming back downriver from the spawning areas. You can still catch a few shad at the place where Amtrak crosses the Susquehanna, and a few hardy pioneer fish are starting to make it all the way to Lambertville. But the bulk of shad in Philadelphia markets now comes from North Carolina, and you better be alert to your timing or even they will be all gone before you've had any. There once was a time when a diner could be identified as a boorish stranger picking gingerly at the strong-tasting fish, or messing around dubiously with the unfamiliar roe served on toast. Nowadays, even lifelong Philadelphians will occasionally behave like that. You put lemon juice on the roe, dummy.

And you filet the fish. The bones of a shad are complex, going both forward and back within the flesh, so you have to be experienced to take a very sharp knife, twist, and turn, duck your shoulders and flip the fish, to produce boneless" shad0. If you don't know how to do that, you may have to bake the fish for hours to melt the bones and make it edible, but tasteless. Such products can be rescued by stuffing them with bread crumbs and spices. When things reach the point where no butcher knows how to produce boneless shad, our culture is on the edge of extinction. The big center for wholesale boned shad is Dill's in Bridgeton, NJ. There is, right now, only one place where you can obtain planked shad. That's the Salem Country Club (if you look respectable they let nonmembers in) out at the point on the Jersey side where Delaware takes a big bend before it flows down to the sea. A shad is planked by splitting it open and nailing it to a board, which is then placed before an open fire in the fireplace. Snap, crackle and wow.

Maybe the conservationists can get these fish back for us. The Eagles will certainly like that; had used to be what mainly sustained the American bird, and the depletion of the shad is part of the near-extinction of eagles. And maybe we can swallow our pride and teach the West Coast how to treat shad with respect. Shad was always an East-coast, Atlantic fish, and there is hardly a river left which has much shad. But someone transported some shad to the Sacramento, California area a century ago -- and they have flourished. Where the fish ladders of the Columbia River used to teem with salmon, nowadays they teem with shad. California likes to think it invents everything in America. Brace yourself for being told they invented shad.

Where Do Shad Go, When They Aren't Around Here?

|

| BAY OF FUNDY |

Some day, we're going to clean up our rivers, and then maybe the shad will come back. Since every female shad produces a couple hundred thousand eggs a season, when the shad come back, there could be a lot of them. We now know some things George Washington didn't know about shad. For example, they all go to the Bay of Fundy, once a year. All of them, whether they spawn in North Carolina, the Delaware, or the Connecticut River.

By tagging them, it was learned that shad swim at a depth of several hundred feet, apparently seeking a certain amount of darkness, which is in turn related to the growth of algae and plankton, their favorite food. So, when the surviving shad go back down a spawning river to the ocean, they head North in a huge counter-clockwise ocean rotation, adjusting their depth to the degree of darkness. Just about the time summering Philadelphians start packing for Bar Harbor, the shad also reach the Bay of Fundy, which is muddy and dark. Fundy is famous for its unusually high tides, so the turbulent water achieves the shad's desired degree of murkiness at about thirty feet instead of the normally deeper waters of the cyclic migration in the open ocean. People who know about these things say that just about every shad on the East Coast passes through the Bay of Fundy in late spring. In the fall, the fish turn around and start to go South again, maybe following the sun, maybe seeking a desired temperature, or both. Somehow or other, this pattern of migration helps them escape predator sharks and seals, as judged by that wholesome entertainment, the examination of stomach contents. Look out for sharks and seals in the open ocean, but striped bass are the big enemies of fingerlings in the spawning rivers. The Hudson River curiously has lots of striped bass lurking among the abandoned piers, and so does the Chesapeake. The Delaware also has a few stripers around the mouth of the Rancocas Creek; go ahead and fish 'em out.

All of this brings us to a suggestion for our tourist bureau. Shad don't eat much when they are on a spawning run, but they will strike at a lure. That is, you don't use worms, you do fly-casting. If we ever got anything approaching the old shad runs in the Spring, you could expect thousands and thousands of eager fly-casters to flock to the Delaware, filling up our marinas, hotels, restaurants, and cabarets. You wouldn't need to advertise a river teeming with eight-pound action-eager fish; the news would spread like magic. The best proof of this claim can be found on the only river on the East Coast which continues to have a classic shad run. The existence of this river was told to me as a sworn secret, but the invitation to try it was given with the assurance that "every single cast results in a strike".

And here's the zinger. Except for that one secret stream, the Delaware is the only major river on the East Coast that doesn't have a dam between the ocean and the spawning grounds. Once these fish have picked a river, they keep coming back to it, forsaking all others. The situation positively cries out for Federal assistance, and the lure-casting fishermen of America demand no less. Presidential elections have been won and lost on less important issues than this one. But just one dedicated congressman could do it, particularly if he sits on the Committee on Fisheries. Bring back our shad and get rewarded with lifetime incumbency that even Gerrymandering can't dislodge.

Life On The River (3)

|

| Darth Mouth Castle |

All over Europe the scene is repeated: a market town and seaport at the mouth of a river, with many miles of riverbank castles in the hinterland. The seaports had to be fortified against pirates, the hinterland against marauding brigands. But the two flows of commerce consisted of baronies upriver feeding the seaport, while secondarily their seaports carried on trade with nearby river-organized economies. From time to time, someone like Julius Caesar, Napoleon, Bismarck or Hitler would try to unify the various river economies, usually unsuccessfully. In fact, the same pattern was seen along the Pacific Coast of South America, until the Incas figured out how to go along the mountain ridge in the far interior, and then come down the rivers from the sparsely populated areas to the maritime settlements at the mouth of the river, whose defenses were planned for enemies from the sea. Philadelphia followed the commercial pattern, but without fortresses and castles.

Because of the vagaries of King Charles II, and underneath that, because of marshes and their mosquito-borne diseases, the Delaware Bay was settled fairly late in colonial times -- and almost entirely by Quakers. The Dutch were interested in fur trading rather than settlement, the Dutch were anyway too few, their sovereign too indifferent, and William Penn took care of the Indians. So the English settlers had no one to fight except other Englishmen, once the French stab at Inca-like strategy was put down in 1753. After 1783, or perhaps 1812, the world finally left us alone. The Delaware Bay and River are essentially free of fortresses, Philadelphia has no castles. The peaceful sixty miles of upper Delaware Bay became lined with big farmhouses, or big Federalist and Victorian mansions. For a century, from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War, and even for a time after that, the history of this peaceful pond reads like a novel by Jane Austen.

As a playground for menfolk, it would be hard to improve on Victorian Delaware Bay. The river was full of fish, notably shad. In the fall, the migrating ducks and geese made for marvelous hunting. In the countryside behind the riverfront, houses were found all the sports having to do with horses; fox hunting, racing, horses shows. The kids could putter around in small sailboats, the adult sailors could sail a yacht to Europe if they wanted to. After John Fitch invented the Steamboat, it was possible to take a daily commute to the best male game of all -- trading, investing and gambling in the financial and commercial center of Philadelphia.

|

| Shad |

Marion Willis Rivinus and Katherine Hansel Biddle wrote a little book in 1973 called Lights Along the Delaware which tells the river story from the female point of view. The woman of the house was sort of the mayor of a little city, organizing the staff, supervising the garden, educating the children, planning the household, and organizing the dinners and social events. Educated and trained to the role, she knew what to do and enjoyed doing it. Jane Austen wrote the handbook. And while the menfolk were essential members of the cast of characters, women were the managing directors. The men were off with their horses, or sailboats, or fishing rods, or their faraway big-deal mergers and acquisitions. True, it was not a notably intellectual community, there was no Edith Wharton, Abigail Adams or Emily Dickinson. You might find some of that in Germantown, perhaps. The professions, law, and medicine, lured the more studious male members away from Society, but the international diplomatic circle was seen as the ideal career for any truly graceful graduates of this environment.

|

| Riverbank Railroad |

As the riverbank was gradually destroyed by railroads and expressways, only a few mansions like Andalusia remain in good repair. Curiously, what endures best are the clubs. The fishing club variously called the Fish House, the Castle, the Colony in Schuylkill, or the Schuylkill Fishing Company of the State in Schuylkill, has moved as many times as the name has changed. Started in 1732, it is the oldest continuously existing men's club in the world. It moved to the Delaware River from the Schuylkill when the Fairmount dam was built, and to its present location at Devon, the estate of William B. Chamberlain in 1937. New members do the cooking, cleaning, and serving, older members tell stories. When the river pollution is finally controlled, they may go back to catching the fish as well as cooking them. There's the Philadelphia Gun Club, which before 1877 was the Public Holiday Shooting Club of Riverton NJ. And then there's the Gloucester (NJ) Fox Hunt, which during the Revolution turned into First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry. After escorting George Washington to the battles of Boston Harbor, The Troop has been an active fighting unit of the National Guard (most recently in Bosnia) as well as a devoted center of male horsemanship between wars. The Farmer's Club, the Agricultural Society, and the Horticultural Society all reflect the rural interests that once predominated just behind the riverfront estates, still thriving aloof after 150 years of suburbia, exurbia and urban revival.

|

| Philadelphia Gun Club |

Although the riverfront industrial slums which destroyed the Philadelphia branch of Jane Austen's gracious living subculture are themselves declining and seem about to go away, it would take a real visionary to imagine how the Grand Life on the River will ever return. The banks of Delaware are much lower than the bank of the Hudson, for example. They make a great place to put high-speed rail lines and even higher speed interstate highways. The patrons of Hyde Park, West Point, and Poughkeepsie are much higher up a cliff and can overlook the river without much noticing an occasional whoosh. The mansions along Delaware have to look right at the tracks. Except for a few places like Bristol which have become isolated on the river side of the tracks and highway, it's not easy to see how you would get from here to there, or when.

Philadelphia Food: Traditional

|

| The Ritz Carlton |

New Orleans is famous for its cooking, and its residents claim it is impossible to get a bad meal in NOLA. New York is famous for its restaurants, where you can get things to eat that are available nowhere else, even though there is lots of bad cooking in that city. Philadelphia is famous for its food, which puts a slightly different twist on the matter. The Delaware Bay provides seafood, the Garden State of New Jersey provides fresh fruit and vegetables, the Pennsylvania Dutch Farm area provides meat and produce, the Diamond State of Delaware is famous for poultry, and lately, the shipping for Chile brings in fruit and vegetables out of normal season. Philadelphia is within easy distance of the very best and freshest of groceries. The city responded with bakeries, meat markets, fish markets, breweries, dairies. One by one, the latest ethnic arrivals brought in new recipes, quickly modified to fit the local style. All of this explains why Philadelphia can be famous for its ice cream, for example, even though it was not invented here as some local patriots carelessly contend.

Snapper soup is certainly one of the traditional Philadelphia dishes. To make it in the traditional way, you have to dedicate a stove for the process. New material is dumped in the top and today's soup is taken out the bottom, imitating the process for making sherry wine. The Old Original Bookbinder's restaurant had such a dedicated stove, but it has gone out of business, apparently leaving the Union League as the only traditional snapper soup source. Philadelphia Pepper Pot Soup is pretty much the same as Snapper soup, substituting tripe for the turtle as the meat base.

Scrapple is not to everyone's taste in this age of cholesterol fears, but it is certainly a locally famous dish, usually served as fried slices for breakfast. Scrapple is actually a mixture of cornmeal mush and Pennsylvania Dutch Puddin', a stew of scrap meats which is also sold as a chilled loaf. Puddin' is a dish for real traditionalists who have inherited low cholesterol to protect them from it. Only one or two old stands in the Reading Terminal market still carry it, and then only at butchering season. The Reading and Lancaster farmers markets are a more dependable source for Puddin', and Scrapple survives as more popular because it can be obtained in cans in the supermarkets. While you are there in a farmers market, you might get a loaf of head cheese, which substitutes gelatin for congealed fat as the binder for cooked meat chips with spices. Among the local heavy breakfasts must be mentioned stewed kidneys on waffles. The local belief is that this surprisingly delicious dish was introduced from Virginia, by steamboat vacationers to Cape May who mixed with Philadelphia vacationers at places like the Chalfonte Hotel, where stewed kidneys can/may still be obtained on Sunday morning.

Cinnamon buns, or Philadelphia Sticky Buns, are a local delicacy with the tradition of coming from Saxony in what is now Germany. The more butter and sugar the better, and real Philadelphians fry the sticky buns for breakfast. Out in San Francisco, they are famous for sourdough bread, while in Philadelphia the locally famous bread is black bread, a form of pumpernickel. Unfortunately, it is easily imitated by putting cocoa in white bread, so you need to lift a loaf before you buy it. Real black bread is as heavy as a cannonball, and about the same size and shape; it's even better with raisins in it. Toasted Crumpets are a Scottish introduction to the town's traditions, ambrosial if you can get fresh crumpets. Crumb cake is another traditional breakfast bun, known as coffee cake in the Dutch country, and imitated in commercial form as Tastykake.

|

| Snapper |

When turtles were more abundant, snapper stew, fried oysters and sherry were favorites, but now terrapin is such a rarity that it is saved for special occasions and special guests. It's usually served in a cream sauce in Philadelphia, whereas cream sauce is called abhorrent in Baltimore. Because of the availability problem, the party dish nowadays is apt to be fried oyster and chicken salad, and even oysters are getting a little scarce.

No one seems to challenge the idea that iced tea originated in Philadelphia, and in the Dutch Country, it is quite common to have iced tea 365 days a year, pitcher after pitcher. Let's not forget meatloaf, and corned beef hash with an egg, which is both perfectly delicious when served by someone who knows how to make them. They sound like leftovers, but it depends on where you get them. In the men's clubs, and in some Reading Terminal Restaurants, they are a star feature of the menu.

|

| Shad |

Around March 15, it is a good idea to ask if shad or shad roe is available. The trick is to get the fish with the bones removed. In recent years, shad is increasingly abundant, but it isn't so easy to find a butcher or chef who knows how to excise the bones while leaving the filet intact. At the moment, just about the only place that serves traditional planked shad is the Salem Country Club, out on the tip of the abrupt bend in the river above Salem, New Jersey. The ceremony is to split the big fish and nail it to a board, which is then placed in the open fireplace to cook, snapping and popping while its marvelous aroma fills the dining area. Owen Johnson once wrote a famous Lawrenceville book about The Tennessee Shad, so other towns must enjoy shad, too, but we wouldn't really know.

Special Philadelphia dishes may be a little hard for the tourist visitor to find. If you click on this link , you'll find a website put together by an enthusiast, who lists some of the better places for a wandering tourist to find local specialties. Philadelphia has quite a few high-toned fancy sit-down restaurants, too, but these are cheap, good, and easy to find.

Philadelphia Food: Ingredients

|

| Super Market |

There was a time when locally grown farm produce was much more critical than it is at present. There were even resort hotels with their own farms that offered fresh vegetables as the main attraction for vacationers, but now almost any supermarket will supply reasonably good produce to most places in the country. Nevertheless, certain things like fresh corn on the cob must be cooked and eaten almost the same day they are picked, and such seasonal local produce is better around Philadelphia than any other metropolitan area.

|

| Campbell Soup Kids |

The states of Delaware and New Jersey were once Atlantic barrier islands, so the sandy loam is particularly favorable for growing asparagus, for example. An asparagus field is planted as perennials, with new shoots harvested by stoop labor fields of asparagus is difficult to plant and quite valuable once established. Tomatoes are annuals, which in their finest form will continuously produce all summer. It's only worth planting "steak" tomatoes, or so-called Jersey Tomatoes, if there is a local market willing to pay premium prices for the fact that the human picker can tell a green one from a red one. The tomato industry which once supplied Campbell Soup to the world has now mostly moved to California where improved varieties of soup-grade tomatoes all ripen simultaneously, thus can be harvested with machinery at a single pass. Lancaster County in Pennsylvania boasts the best topsoil in the country, although it must be admitted that the glaciers dumped topsoil fourteen feet deep around northern Illinois. Such topsoil is almost too valuable to be used for truck gardens. Lancaster County grows fodder for cattle, and the cattle are hidden away in barns where passersby never see them, just as you never see chickens when you drive through Delaware. What visitors see are silos in Lancaster County and chicken sheds in the lower counties, and acres and acres of animal-feed crops (field corn and soybeans) surrounding the farms. A century ago, all those Swamps("wetland") around Delaware Bay held lots of ducks, geese, quail, and other game, but the game is less popular than it used to be. Location, location is always the true source of value, and in this case, the source of good Philadelphia food is the local location of a vast variety of fresh produce.

|

| Brandywine Battlefield |

Somewhere, the story needs to be retold of the mushroom growers of Kennett Square. This little nondescript town near the Brandywine Battlefield at the top of the state of Delaware was the mushroom capital of the world. It stayed that way for generations, by keeping the secrets of the mushroom trade a strict family secret. Among the various oddities was the production around Thanksgiving time of the first crop of the season, which were often as large as grapefruit, and usually only given to members of the family or special friends actually to be carved at the Thanksgiving table next to the turkey. During the Second World War, Franklin Roosevelt (his daughter-in-law was Ethel DuPont, who lived nearby) personally appealed to the mushroom farmers to reveal their secret methods to the makers of penicillin, needed for the war effort. The farmers gave it up, penicillin saved thousands of lives. And nowadays, most mushrooms in American supermarkets are grown in Taiwan, flown in at prices the Kennet Square growers cannot match.

Real estate developers are doing their best to fill up those truck gardens with split-level houses, of course, and the lovers of good food are allies of the lovers of the environment. So, the individual householder needs to know how to find the Red, Blue and Green Dot roadside farm stands along the highway to the Jersey shore, when the Jersey corn, tomatoes, and melons are at their best, or earlier in the year when Jersey berries are available. You need to know about the Reading Terminal Marketplace, the South Philadelphia street markets, the ethnic neighborhood butcher shops and bakeries, the Kutztown Fair and the farmer's markets in Lancaster County. It's surprising what you can order over the internet, but for the really choice fresh produce in season, you have to hunt around a little.

The farmers of South Jersey have traditionally been Quakers. One Quaker family named Taylor has had a farm right next to the Delaware River in Cinnaminson, just north of the Tacony Palmyra Bridge, since the days of William Penn. Taylors signed the 1783 minute of the Yearly Meeting of Quakers to the Continental Congress, advocating an end to slavery. As the Cinnaminson area became built up, the Taylors had a thriving fruit and vegetable stand, which was left unattended. That is, Joe Taylor brought out the corn and other produce and left it on the stand, while the customers just came up and left their money in a box on the same table. No one stole the money for a century, just as no one in the neighborhood ever locked the door of his house. As things evolved, Joe Taylor, Jr. eventually won the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics for discoveries helping to explain the force of gravity. But in time, the family decided to give up the farm and turned it over to the State as a nature preserve. Undoubtedly a major factor in the decision, if not the only deciding factor, was the repeated discovery that people were stealing the money from the vegetable stand box.

|

| Market on Spruce Street |

For the most part, however, the supermarkets and the chefs of Philadelphia's restaurant revolution nowadays just need to go to the South Philadelphia Food Distribution Center, down in the old filled-in swamp and garbage dump area at the foot of the Walt Whitman Bridge. This is Harry Batten's gift to his city. The former chief of the N.W. Ayer advertising agency made it a personal crusade to put across a remarkable transformation in his home town. Until well past the Korean War, wholesale food distribution took place in the streets of the former Society Hill, never mind how historic it is. Traffic was at a crawl, cartons of vegetables were strewn over the streets, the noise and stench of America's Most Historic Square Mile was a disgrace. The city was persuaded to set aside land for the purpose, and the wholesale grocers were persuaded to move their warehouses to one combined location with rail, bridge, highway and local access. Within months of opening, the wholesale grocery business had moved to the new location, where it became an international marvel. Meanwhile, Charles E. Peterson bought a Spruce Street mansion that once belonged to Stephen Girard from the old Spruce Street Osteopathic Hospital for $8,000.00, rehabilitated it in absolutely authentic style, and moved into the new home, himself. Society Hill Restoration had begun, Philadelphia's restaurant revolution had begun, a great many people became millionaires out of the commercial side of the process, tax ratables soared, tourists poured into the Independence Park area and Penn's Landing and the Camden waterfront. It's been a long time since Harry Batten's name was heard much, but he ought to have a bronze statue sixty feet high. As the Quakers say, you can do anything if you have leadership. And leadership is one man.

Lambertville and Lewis Island

|

| Atlantic Shore Railroad |

Recall that open Atlantic shoreline once stretched from Perth Amboy to New Castle, Delaware. Glaciers pulverized the nearby mountains and dumped a huge moraine of sand into the ocean, creating southern New Jersey as an offshore island in geological times. The bay silted up and eventually attached that island to New Jersey. The silting-up probably would have continued for another sixty miles, making Philadelphia a land-locked inland city, except that the true

|

| Delaware River |

Delaware River came tumbling down from the mountains to Trenton, turning sharply right and then maintaining an open shallow channel to the sea. From Lambertville to Trenton, the river drops over a series of small falls or rapids, easily visible except when heavy rains "drown" them.

|

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

So, geography accounts for the scenery and early history of the upper end of Delaware Bay. It's still a beautiful hilly countryside with small antique villages, sparsely populated in spite of two nearby cities. Water power at the Fall Line, and then anthracite from the upstate mountains once encouraged early industry in an area that was rather poor farm country. But the Pennsylvania Railroad then rearranged commerce so that a blossoming New Jersey industrial area withered into quaintness. The early railroads mostly all ran East-West along the rivers, since investors in Atlantic port cities obtained both finance and protection from their state legislatures; railroads had almost reached the Mississippi before any were able to establish North-South connecting spurs. A seaboard trunk line was almost impossible to imagine. Finally, a consortium organized by

J.P. Morgan bullied through the main trunk line running through the bituminous coal areas of Pennsylvania and on to the West, with the major port cities connected by the great Northeast Corridor of the Pennsy. This corridor would run on the Pennsylvania side of Delaware. Industry on the bypassed New Jersey side would just wither and decline, and eventually so would the anthracite cities. Since the original colonies and states all ran from the ocean to the interior, each had a vital political interest in resisting this outcome. Only a strong and brutal corporation could bring it off.

When George Washington was circling around Trenton to attack it on Christmas, a narrow spot up-river with a dozen houses on either side was called Coryell's Crossing or Ferry. That's now Coryell Street in Lambertville, linked to the other side of the river at New Hope, after first crossing a narrow wooden bridge to Lewis Island, the center of shad fishing, or at least shad fishing culture.

The Lewis family still has a house on Lewis Island, and they know a lot about shad fishing, entertaining hundreds of visitors to the shad festival in the last week of April. The river is cleaning up its pollution, the shad are coming back, but they, unfortunately, took a vacation in 2006. At the promised hour, a boatload of men with large deltoids attached one end of a dragnet to the shore, rowed to the middle of the river, floated downstream and towed the other end of the net back to the shore. The original anchor end of the net was then lifted and carried downstream to make a loop around the tip of Lewis Island, and then both ends were pulled in to capture the fish. There were fifty or so fish in the net, but only two shad of adequate size; since it was Sunday, the fish were all thrown back.

But it was a nice day, and fun, and the nice Lewis lady who explained things knew a lot. Remember, the center of the river is a border separating two states. You would have to have a fishing license in both states to cross the center of the river with your net; game wardens can come upon you quickly with a power boat. But the nature of fishing with a dragnet from the shore anyway makes it more practical to stop in the middle, where shotguns from the other side are unlikely to reach you. An even more persuasive force for law and order is provided by the fish. Fish like to feed when the sky is overcast, so there is a tendency on a North-South river for the fish to be on the Pennsylvania (West) side of the river in the morning, and the New Jersey (East) side in the evening. During the 19th Century when shad were abundant, work schedules at the local mills and factories were arranged to give the New Jersey workers time off to fish in the afternoon, while Pennsylvania employers delayed the starting time at their factories until morning fishing was over.

Somehow, underneath this tradition one senses a local Quaker somewhere with a scheme to maintain the peace without using force. Right now, there aren't enough fish to justify either stratagem or force, but one can hope.

Founding Fish

|

| Potomac |

In 2002, John McPhee brought out a perfectly splendid book about fish and fishing history in this region, with particular emphasis on shad. He makes the whole topic remarkably interesting, but you have to be a little wistful about the way he demolished a splendid story of fish in Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War. The book is called The Founding Fish.

As everyone knows, George Washington and the Continental Army were starving and freezing at Valley Forge, a few miles up the Schuylkill, while Major Andre and the other British officers were cavorting downtown with the Tory ladies, grr. The story has long been told that things got to a desperate state at Valley Forge when, lo, the annual shad run was several weeks early and mountains of fish came roaring up the river to the excited shouts of the starving patriots and rescued the raggedy starving Continental Army. It would make a wonderful scene in a movie.

McPhee tells us that George Washington was in fact a shady merchant, having caught and pickled many barrels of shad coming up the Potomac River. The annual shad excitement was no news to him, and it seems quite possible he selected the campsite at Valley Forge with this spring event in mind. Shad was no news to the British, either; there are records of their trying to block off the Schuylkill with nets to prevent the fish from getting upriver to Valley Forge.

Unfortunately, a careful search of letters and records fails to record any shad run earlier than April that year. The rescue of song and story does not appear in contemporary documents. What's more, some unnecessarily diligent scholars have sifted through the garbage heaps of the encampment area, and have only found pig and sheep bones, no shad bones.

Those graduate students undoubtedly deserve to be awarded degrees for their work, especially the digging in garbage part. But nevertheless, it all does seem a pity to ruin a good story that way.

The Swamps of Philadelphia

|

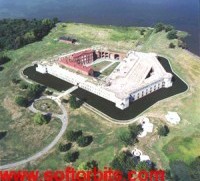

| Fort Mifflin |

Fort Mifflin has been restored, somewhat, and gets a surprising number of visitors at Hallowe'en. The explanation offered is that it seems somewhat spooky. A far greater number of people go to Philadelphia International Airport, or the several sports stadia constructed nearby in a project whose financing is described as "borrowing to expand the tax base". In so doing, visitors travel at some height above the edge of the now-closed Philadelphia Naval Base, with a large number of very large naval vessels in storage, the so-called Mothball Fleet. All visitors are naturally impressed with a view of the wide expanse of the deep and impressive Delaware River. How could such a mighty river be the site of mud islands and narrow channels so shallow that British sailboats couldn't navigate past the Friesian Horses sunk on the bottom?

Well, as water spreads out, it gets shallower. Conversely, as water is compressed into narrower channels, the channel gets deeper, eventually deep enough for nuclear aircraft carriers. So, think back to the days when the Dutch sailed around here, finding the first solid land along the Schuylkill at Gray's Landing, opposite where the University of Pennsylvania now has a row of medical skyscrapers on the West Bank. Everything South of that point was once swamp, so there were miles and miles of shallow water before you got to the Delaware; you could sort of say that the Delaware River was five miles wide at that point. Lots of fish, and ducks, muskrats and beaver.

The main highway to the South, the one that Washington and Jefferson traveled regularly, ran near Gray's Landing, along the edge of the great Philadelphia swamp. Later on, the railroads were built along the same path, and the industrial devastation of that area was accelerated immediately. It was a natural place for "landfill", which is to say it was a good place to dump garbage. By 1940, you had to drive for miles through garbage dumps to reach the Municipal Stadium, where the Army-Navy football game, attended by 105,000 spectators, was played in the freezing winds. The Naval Yard had been moved from the foot of Federal Street to a filled-in island near Fort Mifflin and provided a railroad spur on which the President of the United States regularly parked his private railroad car as he attended The Game. Some enormous liquor distilleries were built near the garbage dumps, and it was difficult to prove which was responsible for the greater odor. World War II caused a great proliferation of war industries on the banks of the river to the South, and the gasoline refineries in the area added to the aroma and river pollution.

In time, the garbage dumps were covered with dirt, and thousands of houses were built where the mosquitoes used to swarm. When the wartime river traffic declined, unemployment set in, and housing got cheaper, even abandoned. With abandoned housing comes slums, and there, in a nutshell, you have South Philadelphia, waiting for an industrial revival. Meanwhile, the swamps are mostly gone, and the river is a lot deeper.

Draining Suburbia

|

| Creek |

Philadelphia's triangle of land between two large rivers once was laced with streams, brooks, and creeks. These were great places to catch fish, especially trout, and they had what poets call mossy banks. Nowadays, these streams are enclosed in culverts or their exposed banks are sharp cliffs of clay. Few people have heard of Indian Brook, which was once the brook that ran through town but is now the brook underneath Overbrook.

The Conservancy has given thoughtful consideration to the consequences of building hard surfaces on top of what was once spongy soil. The streets, the roofs, the driveways of progress, of development, cause immediate runoff of water after a rainstorm instead of allowing seepage into the soil and gravel of the wilderness. The rain of a storm quickly surges into the storm sewers, and surges into the neighboring creeks, scouring the banks in a flood surge. The grass slopes cannot withstand such a housing, leading to sharp clay banks, which become undermined by later storms, toppling trees. The clay material from the banks makes the streams muddy, and the deposits of clay suffocate the insect larvae and fish eggs on the stream bottom. It's perhaps true that there are fewer mosquitoes, but there are no fish. The matter is compounded by the heating of the water as it drains over large sunlit surfaces like shopping mall parking lots, and the different water temperature in the streams changes the insect and fish content, too.

It's almost hopeless to do anything useful in the downtown city areas, where the former streams are not only enclosed in pipes but run underneath skyscrapers. There may even be too much disruption involved to contemplate doing anything useful in towns which allowed storm sewage and sanitary sewage to flow in the same pipes. But it would be a comparatively simple thing to divert rainwater into gravel driveways or out over lawn areas since the goal is to slow its flow into the streams rather than dispose of it. Local ordinances could require such forethought for new construction, and perhaps make construction permits conditional on it. Many suburban homeowners would probably follow suit voluntarily, and gradually the situation might come under control with education and minor pain.

There are other approaches that would get results quicker. In present China, "infrastructure" is upgraded much more directly. One recent visitor was discussing the problem of construction in an area where there was a Chinese town. He was told not to worry about it. The next time he visited the area, that town would be gone.

Native Habitat

|

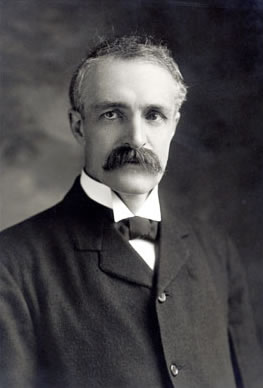

| Gifford Pinchot |

Teddy Roosevelt's friend Gifford Pinchot is credited with starting the nature preservation movement. He became a member of the Governor's cabinet in Pennsylvania, so Pennsylvania has long been a leader in the formation of volunteer organizations to help the cause. Sometimes the best approach is to protect the environment, letting natural forces encourage the growth of butterflies and bears in a situation favorable to them. Sometimes the approach preferred has been to pass laws protecting threatened species, like the eagle or the snail darter. Sometimes education is the tool; the more people hear of these things, the more they will be enticed to assist local efforts. The direction that Derek Stedman of Chadds Ford has taken is to help organize the Habitat Resource Network of Southeast Pennsylvania.

|

| butterfly |

The thought process here is indirect and gentle, but sophisticated; one might call it typically Quaker. Volunteers are urged to create a little natural habitat in their own backyards, planting and protecting plant life of the sort found in America before the European migration. If you wait, some insects which particularly favor the antique plants in your garden will make a re-appearance, and in time higher orders like birds that particularly favor those insects, will appear. The process of watching this evolution in your own backyard can be very gratifying. To stimulate such habitats, a process of conferring Natural Habitat certification has been created. In our region, there are over three thousand certified habitats.

Of course, you have to know what you are doing. Provoking people to learn more about natural processes is the whole idea. For example, milkweed. That lowly weed is the source of the only food Monarch butterflies will eat, so if you want butterflies, you want milkweed. For some reason, perhaps this one, the Monarch is repugnant to birds, so Monarchs tend to flourish once you get them started. After which, of course, they have their strange annual migration to a particular mountain in Mexico. Perhaps milkweed has something to do with that.

|

| Empress tree |

If you plant trees and shrubs along the bank of a stream, the shade will cool the water. That attracts certain insects, which attract certain fish. If you want to fish, plant trees. And then we veer off into defending against enemies. The banks of the Schuylkill from Grey's Ferry to the Airport are lined with oriental Empress trees, with quite pretty purple blossoms in the Spring. These trees seem to date from the early 19th Century trade in porcelain (dishes of "China" ) on sailing vessels. The dishes were packed in the discarded husks of the fruit of the Empress tree, and after unpacking, floated down the Schuylkill until some of them sprouted and took root. Empress trees are certainly an improvement over the auto junkyards hidden behind them. On the other hand, Kudzu is an oriental plant that somehow got transported here, and loved what it found in our swamplands. Everywhere you look, from Louisiana to Maine, the shoreline grasslands are a sea of towering Kudzu, green in the spring, yellow in the fall. It may have been an interesting visitor at one time, nowadays it's a noxious weed. So far at least, no animals have developed a taste for Kudzu, and no one has figured out a commercial use for it. When an invasive plant of this sort gets introduced, native habitat and its dependent animal life quickly disappear. So, in this situation, nature preservation takes the form of destroying the invader.

|

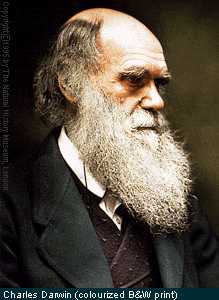

| Charles Darwin |

But where is Charles Darwin in all this? The survival of the fittest would suggest that successful aggressors are generally fitter, so evolution favors the victor. Perhaps swamps are somehow better for being dominated by Kudzu, pollination might be enhanced by killer bees. At first, it might seem so, but if the climate or the environment is destined to be in constantly cycling flux, diversity of species is the characteristic most highly desired. For decades, biologists have puzzled over the surprising speed of adaptation to environmental change. Mutations and minor changes in species seem to be occurring constantly, and most of them are unsuccessful changes. But when ocean currents change, or global warming occurs, or even man-made changes in the environment alter the rules, we hope somewhere a favorable modification of some species has already occurred standing ready to take advantage of the changing environment. Total eradication of species variants, even by other species which are temporarily better adapted, is undesirable. In this view, the preservation of previously successful but now struggling species is a highly worthy project. The meek, so to speak, will someday have their turn, will someday inherit the earth. For a while.

|

| St. Lawrence Seaway map |

And finally, there are variants of the human species to consider. To be completely satisfying, a commitment to preserving "native" species in the face of aggressive new invaders must apply to our own species. Surely, a devotion to preserving little plants and insects against the relentless flux of the environment does not support a doctrine of driving out Mexican and Chinese immigrants at the first sign of their appearance, like those aggressive Asian eels plaguing the St. Lawrence Seaway?. Here, the answer is yes, and no. For the most part, invasive species are aggressive mainly because they find themselves in an environment which contains no natural enemies. If that is the case, fitting the newcomers into a peaceful equilibrium is a matter of restraining their initial invasion long enough for balance to be restored through the inevitable appearance of natural enemies. So, if we apply our little nature lessons to social and economic issues related to foreign immigration, the goal becomes one of restraining an initial influx to a number which can be comfortably integrated with native tribes and clans. In the meantime, we enjoy the hybrid vigor which flourishes from exposure to new ideas and customs.

In the medium time period, that is. For the long haul, if the immigrant tribes really do have -- not merely a numerical superiority -- a genetic superiority for this environment, perhaps we natives will just have to resign ourselves to retreating into caves.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1219.htm

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

|

| Germantown Map |

Chestnut Hill really is a big hill poking up in the middle of Philadelphia, and Germantown Avenue follows an old Indian trail from the Delaware River right up to that hill. The waterfront area of the city has been built and rebuilt to the point where it's now a little hard to say just where Germantown Avenue begins. From a map viewpoint, you might look for a four-way intersection of Frankford Avenue, Delaware Avenue, and Germantown Avenue, underneath the elevated interstate highway of I-95. The present state of demolition and rubble heaps suggests that a Casino might be built there sometime soon, politics and the Mafia permitting.

|

| Fair Hill Cemetery |

Although Germantown Avenue has wandered northwestward from this uncertain beginning for over 300 years, up to the rising slope of the town toward Broad Street, it is now rather difficult to make out anything but industrial slum along its path which could be called historic. There is hardly any structure standing which has a colonial shape, and no Flemish bond brickwork is seen in the tumble-down buildings. When with the relief you finally approach Temple University Medical Center at Broad Street, the Fair Hill cemetery does show some effort at preservation, and a sign says that Lucretia Mott is buried there. But that's about all you could photograph without provoking suspicious stares. Here's the first of four segments of Germantown Ave., and it's a pretty sorry sight.

|

| Chew Mansion |

Crossing Broad Street, the busy intersection suggests 19th Century prosperity in its past, and on the west side of Broad, you can start to see signs of historic houses, either in colonial brickwork or grey fieldstone. The road gets steeper as you go west past Mt. Airy, where it almost brings tears to the eyes to see brave remnants of another time. George Washington lived here for a while, and the Wisters, Allens, and Chews; Grumblethorp and Wyck. The huge stone pile of the Chew Mansion glares at the imposing Upsala mansion, where British and Americans lobbed artillery at each other during the Battle of Germantown. Benjamin Chew the Chief Justice built this house as a summer retreat, to get away from Yellow Fever and such, and started the first migration to the leafy suburbs. His main house was on 3rd Street in Society Hill, next to the Powels and where George Washington stayed. At the peak of the hill in Chestnut Hill, a suburb within the city. Germantown Avenue rather abruptly goes from the relics of Germantown to the charming elegance of Chestnut Hill, but during a recession, it frays a little even there. At the very top is the mansion of the Stroud family, now in the hands of non-profits; across the road in Chestnut Hill Hospital, once the domain of the Vaux family. Then down the hill to Whitemarsh, where the British once tried to make a surprise raid on Washington's army. As you cross the county line into Montgomery County, it's conventional to start calling the Avenue, Germantown Pike. Germantown Pike was in fact created in 1687 by the Provincial government as a cart road from Philadelphia to Plymouth Meeting. Farmers used to pay off their taxes by laboring on the dirt road, at 80 cents a day. Germantown Pike, Ridge Pike, Skippack Pike, Lancaster Pike, and others are a local reminder that Pennsylvania was always the center of turnpike popularity; that's how we thought roads should be paid for. The present governor (Rendell) hopes to sell off some better-paying turnpikes to the Arabs and Orientals, possibly imitating Rockefeller Center by buying them back and reselling them several times by outguessing the business cycle. Parenthetically, the Finance Director of another state at a cocktail party recently snarled that the purpose of privatizing state infrastructure was not to raise revenue, but to provide collateral for more state borrowing. He wasn't at a tea party, but he may soon find himself there.

From a modern perspective, the third segment of the Germantown road runs from Chestnut Hill to Plymouth Meeting, with lovely farmhouses getting swallowed up by intervening, possibly intrusive, exurbia. The township of Plymouth Meeting is a hundred years older than Montgomery County, having been built to be near a natural ford in the Schuylkill River. Norristown, a little downstream, is the first fordable point on the Schuylkill, with Pottstown making a third. Plymouth's colonial character survived a period of industrialization based on local iron and limestone, and has established several prominent schools for the surrounding area. But the construction of a substantial highway bridge attracted a large and busy shopping center. The shopping center looks as though it will eradicate the quaint historical atmosphere more effectively than industrialization ever could.

The fourth and final segment of Germantown Pike starts at the Schuylkill and goes over rolling countryside to its final destination at Perkiomenville, where it joins Ridge Pike at the edge of the Perkiomen Creek. That's an Indian name, originally Pahkehoma. Perkiomenville Tavern claims to be the oldest inn in America, although that honor is contested by another one along the Hudson River near Hyde Park. The WPA during the Great Depression constructed a large park along the Perkiomen Creek for several thousand acres of camping and fishing, so Perkiomenville has several large roadhouse restaurants and antique auctions for bored wives of the fishermen. In the V where Ridge Pike and Germantown Pike come together, a dozen or more colonial houses are tucked away in a town called Evansburg. This formerly Mennonite terminus of Germantown Pike obviously still has a lot of charm potential, and its local inhabitants are very proud of the place. But it's easy to zip past without noticing the area, which includes an 8-arch stone bridge, said shyly to be the oldest in the country. It's hard to know whether you wish more people would visit and appreciate; or whether you are happy that obscurity might permit it to survive another century or so.

|

| Chestnut Hill Hospital |

The name change of the Germantown road from Avenue to Pike is probably not precisely where the turnpike began, but it is now notable for some pretty imposing mansions, standing between the humble and even somewhat dangerous slums along Delaware, and the charmingly humble but well-preserved Mennonite villages, at the other end. It is arresting to consider the two ends, whose houses were built at the same time; only the Mennonites endure. Somewhere just beyond the Chestnut Hill mansions is an invisible line. West of that point, when you say you are going to town, you mean Pottstown. When you say you are going to the City, you mean Reading. And as for Philadelphia, well, you went there once or twice when you were young.

Turtles and Bananas

|

| Snapper Turtle |

Snapper soup, the old Philadelphia stand-by, probably got its name from snapping turtles. But for a century or two, the ingredient turtles came from the Caribbean or even further south. The huge tortoises of the Galapagos were once picked up by whalers, stored alive in the hold of the ship, to be used as needed by the sailors. Only the paws were edible. In time, the more usual imported turtle had a diameter of two feet and was picked up on South American voyages. By the end of the nineteenth century, the steamship trade was dominated by Moore-McCormack, United Fruit, and the Grace lines, who all sailed much the same kind of steamship, carrying a few passengers and a lot of cargo. Generally speaking, the cargoes going out of American East Coast ports consisted of machinery, while the cargoes coming back were bananas. If a ship carried more than twenty-five passengers it was required to have a physician on board, so passengers were either just a handful or about a hundred in number; it made for two general classes of vessel.

As a throwback to the Galapagos business of the sailing-vessel era, United Fruit would always bring home about fifty live turtles in the hold for the Waldorff in New York. It's now unclear who supplied Bookbinders and the Union League in Philadelphia, but it was apparently the same sort of arrangement: turtles came back with the bananas. It's getting hard to find snapper soup anymore; the explanation is probably mixed up with disturbances to this historical source.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1481.htm

Hidden River

.jpg)

|

| Schuylkill River |

In Dutch, Schuylkill means "hidden river", thus making it redundant to speak of the Schuylkill River. As soon as you become aware of this little factoid, you start to come across Philadelphians who do indeed speak of the Schuylkill in a way that acknowledges the origin of the term. To give it emphasis, it is common to speak of the "Skookle". The point comes up because cruises have started to leave from the dock at 24th and Walnut Streets, where it becomes quite noticeable that the Schuylkill really is rather hidden as it winds seven miles south to the airport, in contrast to the wide-open vista we all are accustomed to seeing from the Art Museum northwards.

The bluff at Gray's Ferry, where the University of Pennsylvania's new buildings now dominate the scene, was originally the beginning of dry land, or the end of the rather large swamp, through which the river winds its way essentially shaded by trees along the riverbank. Never mind the junkyards and auto parks you happen to know lurk behind the trees on the west side or the oil tanks which loom above the trees on the south bank. As evening closed in on the riverboat, the gaily lit towers of center city were looming in the stern, but some fishermen along the bank proudly held up a respectable string of six or seven rather large catfish. If you are there in the evening, the river has the same feeling of wilderness that the Dutch traders would have experienced three hundred years earlier. No swans, however. There were many reports in the Seventeenth Century of large flocks of swans sailing around the entrance of the Schuylkill into the Delaware River. A noted local ornithologist on the recent cruise remarked that forty or fifty species of birds are found there. Even a flock of owls still live within the city limits. You don't see owls, even if you are an ornithologist; their presence is made known by taking recordings of the sounds of the night.

|

| Fort Mifflin |

The geography of swampy South Philadelphia was created by the abrupt bend in the Delaware River at what is now thought of like the airport region. As the river flows at the bend, sediment is deposited in mud flats that once created Fort Mifflin of Revolutionary War fame, and later Hog Island of the Naval Yard, home of the hoagie. Swans are beautiful creatures, but they seem to like a lot of mud. The lower Schuylkill is tidal, and the industrial waste of the region is cleaned out of the land by cutting drainage ditches laterally from the river, flooding the lowlands as the tide rises, and draining it again as the tide falls. This cleansing seems to be working, as judged by the return of spawning fish. And maybe mosquitos, as well, but it would seem rude to inquire.

The Bartram family seems to have known how to make use of river bends and riverbanks, placing the stone barn and farmhouse higher up the bank, but below the bluff of Gray's Ferry forces a bend in the Schuylkill, below which of course flatlands were created. It's a peaceful place, now made available for tours and excursions by placing a landing dock on metal pilings so that it can ride up and down with the tides. The great advantage is that riverboat landings are no longer restricted to two a day, at high tide, with limited time to visit before the tide falls again. Bartram recognized how popular strange plants from the New World would be in England, and his exotic plants were quite a commercial success. Nowadays the big sellers are Franklinia Trees, available the first week in May. The last Franklin (named of course for his friend Benjamin) ever found growing in the wild, was the one John Bartram found and nurtured. Every Franklinia is thus a descendant of this one. They look rather like dogwood but bloom in the early fall. If it suits the fancy, a dogwood next to a Korean dogwood which blooms in June, next to a Franklinia, can make a continuous display of bloom from May to October. And best of all, no one will appreciate it, unless they are in the know.

Water Works, Emblem of the Past

|

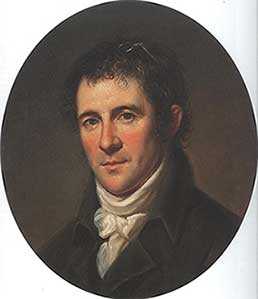

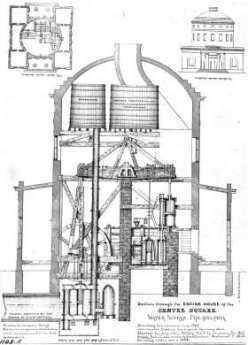

| Benjamin Henry Latrobe |

Philadelphia didn't really want the national capital to move to Washington DC, but the yellow fever epidemics, brought from Haiti by refugees, made it politically impossible to reverse the decision to move. We now know that Yellow Fever is transmitted by mosquitoes, but there were enough trash and pollution lying about the that it was plausible that polluted water was the cause. With no time to waste, water was piped in, through wooden pipes, from the comparatively pristine Schuylkill to a pumping station in Center Square, where City Hall now stands. Even today, no one wants a water tower in the neighborhood, so Benjamin Henry Latrobe made it look like a Roman Temple, thereby introducing classical architecture to Philadelphia, and starting quite a trend. The new system worked well enough from 1801 to 1815, when the new city outgrew it. Therefore, a new pumping system was built at the base of Faire Mount, where William Penn once planned to have a mansion, and was attached to Latrobe's wooden pipe system. In a unique and ingenious way,

|

| Latrobe Water Works |

Frederic Graff pumped Schuylkill water up to a series of reservoirs on top of Faire Mount, utilizing a water stack to maintain constant pressure. The classical architecture was continued, parks and decorative gardens were placed around it, and admirers came from around the world to marvel. Meanwhile, Latrobe's original building could now be torn down, providing room for City Hall, which was planned to be the tallest building in the world, although the French sort of cheated and put up Eiffel Tower, which in a sense really isn't a building. Meanwhile, Philadelphia and the rest of America kept growing and growing, leading to industrial plants along the Schuylkill all the way up to Pottsville, where the anthracite came from. The pure sparkling municipal water of which Philadelphia was so proud soon became a stinking sewer, and the Civil War encampments accelerated the process.

|

| Frederic Graff |

Following the lead of the Philadelphia College of Physicians, the concept of Fairmount Park emerged from clearing the banks of the river, and the Wissahickon Creek, of industry. The Philadelphia Water Works thus became the southern anchor of the largest city park in the world, including the building of Laurel Hill Cemetery, which had sanitary overtones which were embarrassing to discuss. Philadelphia led the world in adapting to this particular feature of the Industrial Revolution, and the insights of Louis Pasteur. By 1890, however, the system was again outmoded, and Philadelphia water became the butt of every joke. Between 1815 and 1840 the wooden pipes were replaced by iron ones. Robert Morris's old estate of Lemon Hill was acquired by Fairmount Park and used to construct a second reservoir on the neighboring hill. More about that second reservoir, in another blog.

Eventually, there would be more reservoirs at Belmont and Green Lane. But the city's new reputation for foul water was deserved. Deaths from typhoid fever rose to 80 per 100,000 residents before a water filtration system was installed; deaths from typhoid promptly fell to 2 per 100,000. Statistics on hepatitis were not available, but virus diseases must have been a serious hazard under primitive conditions of filtration, aeration and chlorination -- as they still are in many third-world countries, and in most southern European nations before 1950. As late as 1950 in Philadelphia, it was considered witty for a dowager to accept a drink from her hostess, saying "I'll drink absolutely anything, except Philadelphia water -- and 'Coke' ". The implication was that alcohol sterilizes water, which of course it doesn't, and also that absolutely everybody knows that Philadelphia has terrible water, whatever that means.

A reputation like that is bad for the city, making it harder to persuade workers and business to locate here, but the traditions underlying this response are quite ancient. Back in the days when water came from your own well, whole neighborhoods would move to new unspoiled areas to seek cleaner water and regions where the local privies were not yet mature. It takes quite a lot to persuade people to abandon the investment in a home or mansion as in Society Hill, and build a new one in a nearby undeveloped region. Particularly when the germ theory was not yet available to explain the issues with precision, pulling up stakes for a new neighborhood was an accepted reaction to almost any threat.

|

| Water Works Today |

However, strenuous exertions for half a century have made Philadelphia water safer, tastier, and far cheaper than bottled water. The recent trend of young people to walk about sucking a three dollar bottle of water drives the Philadelphia Water Department up to a wall. For example, 25% of bottled water comes straight from the tap. The inspection standards for public water are much stricter than for commercially bottled water, whose safety is in large part secondary to the safety of the tap water from which it is derived. True, public water is chlorinated, but then it is also fluoridated, putting legions of dentists out of business. In Philadelphia, that's the main difference justifying the rather appalling price difference, and the accumulation of plastic bottles in various trash heaps.

The recent advances in Philadelphia's water can in part be traced to Ruth Patrick, now over a hundred years old but the world's foremost expert on streams and water, and to the persistent professionalism of the Philadelphia Water Department. Perhaps, though, it may take a century of slander about water to persuade the politicians to keep their hands off the Water Department. It does take a lot of tax money to implement the third step in the process of cleaning up the water supply, which is the purification of wastewater. For centuries, the guiding principle was to obtain and maintain pure water at the source; wastewater was flushed down the sewer to go back out to the ocean. However, seven times as much water is removed from Delaware, as it flows past the city. That is, the water now recirculates through the sewage system seven times before it is turned over to residents of lower Delaware Bay. The expensive and elaborate -- but scarcely visible -- system of treating sewage in various sewage treatment centers has now resulted in returning water to Delaware in better condition of purity than it had when it came down past Bucks County.

But it costs lots of bucks, and nobody seems to notice the water. People only notice the bucks.

Heron Rookery on the Delaware

|

| Great Blue Heron |

When the white man came to what is now Philadelphia, he found a swampy river region teeming with wildlife. That's very favorable for new settlers, of course, because hunting and fishing keep the settlers alive while they chop down trees, dig up stumps, and ultimately plow the land for crops. As everyone can plainly see, however, the development of cities eventually covers over the land with paving materials; it becomes difficult to imagine the place with wildlife. But the rivers and topography are still there. If you trouble to look around, there remain patches of the original wilderness, with quite a bit of wildlife ignoring the human invasion.

|

| Heron Nests |

Such a spot is just north of the Betsy Ross Bridge, where some ancient convulsion split the land on both sides of the Delaware River; the mouth of the Pennypack Creek on the Pennsylvania side faces the mouth of the Rancocas Cree on Jersey side. In New Jersey, that sort of stream is pronounced "crick" by old-timers, who are fast becoming submerged in a sea of newcomers who don't know how to pronounce things. The Rancocas was the natural transportation route for early settlers, but it now seems a little astounding that the far inland town of Mt. Holly was once a major ship-building center. The wide creek soon splits into a North Branch and a South Branch, both draining very large areas of flat southern New Jersey and making possible an extensive network of Quaker towns in the wilderness, most of whose residents could sail from their backyards and eventually get to Europe if they wanted to. In time, the banks of the Rancocas became extensive farmland, with large flocks of farm animals grazing and providing fertilizer for the fields. Today, the bacterial count of Delaware is largely governed by the runoff from fertilized farms into the Rancocas, rising even higher as warm weather approaches, and attracting large schools of fish. My barber tends to take a few weeks off every spring, bringing back tales of big fish around the place where the Pennypack and Rancocas Creeks join Delaware, but above the refineries at the mouth of the Schuylkill The spinning blades of the Salem Power Plant further downstream further thin them out appreciably.

Well, birds like to eat fish, too. For reasons having to do with insects, fish like to feed at dawn and dusk, so the bottom line is you have to get up early to be a bird-watcher. Marina operators have chosen the mouth of the Rancocas as a favorite place to moor boats, so lots and lots of recreational boaters park their cars at these marinas and go boating, pretty blissfully unaware of the Herons. Some of these boaters go fishing, but most of them just seem to sail around in circles.

|

| As Seen From Amico Island |

Blue herons are big, with seven-foot wingspreads as adults. Because they want to get their nests away from raccoons and other rodents, and more recently from teen-aged boys with 22-caliber guns, herons have learned to nest on the top of tall trees, but close to water full of fish. And so it comes about that there is a group of small islands in the estuary of the Rancocas, where the mixture of three streams causes the creek mud to be deposited in mud flats and mud islands. There is one little island, perhaps two or three acres in size, sheltered between the river bank and some larger mud islands, where several dozen families of Blue Herons have built their nests. One of the larger islands is called Amico, connected to the land by a causeway. If you look closely, you notice one group of adult herons constantly ferries nest building materials from one direction, while another group ferry food for the youngsters from some different source in another direction. At times, diving ducks (not all species of ducks dive for fish) go after the fish in the channel between islands, with the effect of driving the fish into shallow water. The long-legged herons stand in the shallow water and get 'em; visitors all ask the same futile question -- what's in this for the ducks? The heron island is far enough away from places to observe it, that in mid-March its bare trees look to be covered with black blobs. Some of those blobs turn out to be heroes, and some are heron nests, but you need binoculars to tell. When the silhouetted birds move around, you can see the nests are really only big enough to hold the eggs; most of the big blobs are the birds, themselves. There are four or five benches scattered on neighboring dry land in the best places to watch the birds, but you can expect to get ankle-deep in the water a few times, and need to scramble up some sharp hills covered with brambles, in order to get to the benches. In fact, you can wander around the woods for an hour or more if you don't know where to look for the heron rookery. Look for the benches, or better still, go to the posted map near the park entrance south of the end of Norman Avenue. There are a couple of kiosks at that point, otherwise known as portable privies. Strangers who meet on the benches share the information supplied by the naturalists that herons have a social hierarchy, with the most important herons taking the highest perches in the trees. That led to visitors naming the topmost herons "Obama birds", and the die-hard Republicans on the benches responding that the term must refer to dropping droppings on everybody else. That's irreverent Americans for you.

There is quite a good bakery and coffee shop just north on St. Mihiel Street (River Road), and the new diesel River Line railroad tootles past pretty frequently. That's the modern version of the old Amboy and Camden RR, the oldest railroad in the country. It now serves a large group of Philadelphia to New York commuters, zipping past an interesting sight they probably never realized is there because they are too busy playing Hearts (Contract Bridge requires four players, Hearts are more flexible). However, there's one big secret.

The birds are really only visible in the Spring until the trees leaf out and conceal them. Since spring floods make the mud islands impassible until about the time daylight savings time appears, there remains only about a two-week window of time to see the rookery, each year. But it is really, really worth the trouble, which includes getting up when it is still dark and lugging heavy cameras and optics. Dr. Samuel Johnson once remarked that while many things are worth seeing, very few are worth going to see. This is worth going to see.

And by the way, the promontory on the other side of the Rancocas is called Hawk Island. After a little research, that's very likely worth going to see, too.

Marcellus Shale Gas: Good Thing or Bad?

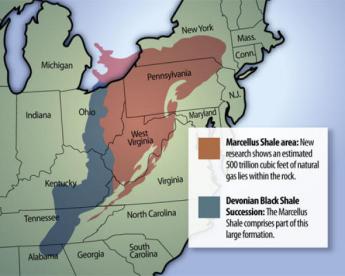

|

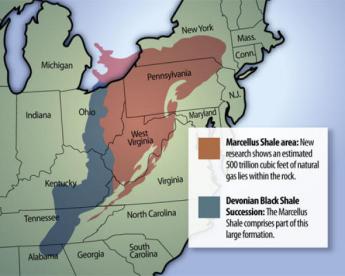

| Marcellus Shale |

Soon after discovering widespread hard and soft coal, Pennsylvania found in Bradford County it also had oil. Local oil was particularly "sweet", with a low sulfur content. Long after much cheaper oil (cheaper to extract, that is) was found in Texas and Arabia, Pennsylvania oil was prized for the special purpose of lubricating engines, which commanded a higher price. This discovery of oil in the western part of the state also provided a vital competitive advantage for local railroads. Other east-west railroads like the New York Central and the Baltimore and Ohio lacked a dependable return cargo like this, so the Pennsylvania Railroad lowered prices and became the main line to the west for a century. Refineries were built in Philadelphia, and continue to dominate Atlantic coast gasoline production, even though the source of crude oil is mostly from Africa. When oil and coal declined in use, Pennsylvania's industrial mightiness declined, too. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh lost much of their competitive advantage, while the center of the state just about went to sleep. When even Texas oil later ran low, America's industry turned to computer-improved productivity to keep its prices competitive, helping California at the expense of Pennsylvania. The bleakness for Pennsylvania may not last, however. Suddenly, we discover we have another enormous source of cheap energy, shale gas.

It's rather deep, however, even deeper than our supply of fresh water. The next layer below surface minerals is porous rock filled with fresh water, the so-called aquifer. Gas bearing shale is layered just under the aquifer. We'll return to the aquifer later.

There is and will be abundant oil in the world, well into the future; but cheap oil has been selectively depleted. When military and economically weak nations like the Persian Gulf had cheap oil, only transportation costs were irksome. But now Russia is emerging as an oil-rich state, previously impoverished states like Iran are asserting themselves, the existence of an international oil cartel becomes more threatening because it reinforces oil price with military threats. Raw material discoveries -- gold rushes -- are always destabilizing because they are tempting to the dictator mindset. That's known in the political literature as the source of the "Dutch Disease", not because Netherlanders are aggressive, but because North Sea oil discoveries destabilized the politics of even that little peaceful nation. America has now made a universal decision to establish energy independence. It once was credible to make predictions that in a decade or two, we would run out of competitively priced energy. To be both rich and weak invites aggression and we knew it.

|

| Gas Drilling |

There's little question America is profligate with its energy, so the need for energy conservation is undisputed. Actually, we are already five times more efficient with energy use than China is; furthermore, we have improved energy efficiency by 20% while China has defiantly worsened. We'll do better, but unfortunately, our immense investments in inefficient home heating and transportation are too costly to discard abruptly in both cases. There is also little question that American research and development of alternative energy sources has been neglected, while China is subsidizing R & D appreciably. In our frenzy, converting food into gasoline by subsidy is a bad joke, electric cars are subsidized and widely described as "Welfare buggies", wind power is twice as costly as carbon-sourced energy and needs better battery development to be able to store it, atomic energy has been encouraged by the French government, but totally held back by ours, in response to public anxieties. The long and the short of it is this: we face a fifteen-year period of doubtful energy sources, a vulnerability our international competitors and enemies might easily use against us.