1 Volumes

Handbook for Health Savings Accounts

New volume 2015-07-07 23:31:01 description

FUTURE VERSIONS

Some ruminations about health financing, written while we wait for the Supreme Court to announce its decision on King v.Burwell.

Waiting for Roberts

It seemed foolish to publish a book on healthcare financing, just on the eve of the United States Supreme Court announcement of what it had decided about Obamacare. Why not wait a little? So I got ready for the announcement by writing half a book and imagining several potential endings. At the end of this section, I plan to add a comment about what the Court did decide, which may be a long or short commentary, depending.

First, let me summarize the book up to this point. The Health Savings Account has had thirty years to ripen and mature, and it could be described as moderate success in supplementing the existing system of employer-dominated health care. HSA saves money for most subscribers, and even makes money for a few people who are shrewd about finances.

When President Obama hammered the Affordable Care Act past a reluctant Congress in 2008, the Health Savings Account developed a new mission. It had been originally devised as an alternative to a tired old system of employer-based health insurance. With Obamacare as a new issue, it got contrasted with a new and untried system, whose direction and purpose had been left quite unclear. With dozens of flaws, the employer-based system had created a great need for reforms, but the Affordable Care Act addressed almost none of them, and it was uncertain whether it ever would. In my view, the purpose of the ACA was to seize control of the finances, after which the President would be able to reform whatever he pleased. First, defeat the enemy, and then announce what your plans are.

That left me with a quandary. I strongly believe in reform, but I strongly resist a blank check. So I decided to write down my views on Health Savings Accounts, in case the public wanted to make use of them during the period when -- by default -- we continued to operate under the old employer-based system. That was particularly vexing, because employers seemed to be the strongest opponents of the new system, and delayed its implementation by at least two years. My strongest opinion was, the public didn't seem to understand how good Health Savings Accounts were, because their best features are latent, hidden within what seem like simple ideas. Their advantages begin to emerge when you encounter difficulties with alternatives. With HSA, almost every problem you encounter seems to uncover a ready-made solution, whereas a flawed concept usually leads to more problems every time you try to fix something.

But now we have reached a point where it is natural to ask how much further we could take Health Savings Accounts. For that, we need an organizing theme. The most natural theme is that Americans would really like to give outstanding medical care to everyone, with perhaps a few points of hesitation. We are not sure the nation can afford to give the style of care we admire, to everyone. Since the employer-based system was mainly criticized for being so costly, and since what we could see of Obamacare was going to be even more expensive, it looked like the end. There seemed a significant danger that making things better for the poor would be paid for by making them worse for the rest of us. By speaking to community groups I had the feeling that elderly people, women, in particular, are not so much in love with Medicare, as fearful it will be stripped to pay for Obamacare. All fifty states have Medicaid programs for the indigent, and all fifty of them are under-funded. That raises the question of how genuinely the public wants to give good care to the poor. There's one exception, however; rich folks, the top one percent, do seem to have a genuine wish to help the poor, no matter how populists denounce them. The rest of the country is often perilously close to competing with poor people and is therefore uneasy about being upended by a leader who wants to spend their money helping the competition. There's a lot of churning between the classes in America; in Thomas J. Stanley's The Millionaire Next Door we read that most millionaires in this country made the leap upward in a single generation.

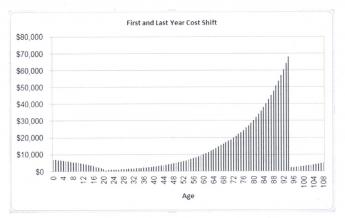

There's another obstacle to expensive universal care, which the public recognizes only dimly. The whole medical system is already riddled with cost-shifting, at every level. The family unit cross-shifts within family insurance plans. Surgeons support the "feeders" with cross-shifted hospital costs. The rich in private rooms are charged more than the middle-class in semiprivate rooms, for the same care. The doctors in blue-stocking districts pay for medical society services of free-loading doctors in poor neighborhoods. Every conceivable cost-shifting strategy has been used up to smooth out cost differences and for hardly any other reason.

Grandpa Gives a Gift to Grandchildren. But one vehicle for cost-shifting hasn't been analyzed very well. Almost all money in the medical system ultimately depends on a single age group, from age 21 to 66. Parents almost always pay for their children, and the elderly plan to fall back on their working children if resources run low, although they hope not to. To a limited extent, the pricing of health insurance premiums shifts money around, but holds back uneasily, when it comes to shifting between family units. The Scandanavians regard whole language groups as "family" to a much greater degree than we do, explaining most of their different attitude about nationalizing health costs. Through most of these schemes runs the idea of taxing the necessary money into a government pool, and then redistributing it to the worthy poor. The resistance to this approach mostly concentrates on the political step in the middle, easily denounced but leaving true public attitudes unclear. A more serious concern would be the cost of an extra layer of administration, but most substitutes just seem to add one of their own.

So it seemed only natural to ask whether some of the unused surplus generated by the conservative elderly might be used to fund the costs of having grandchildren. Perhaps a grandchild would be better accepted than a stranger. Some resistance comes from misjudging longevity, but most of it is an underestimation of the way earnings accelerate during late-stage interest compounding. True, it might take eighty years to break even with generational transfer, but even that could be turned to the advantage of eight doublings @ 7%. Since we are dealing with paying childhood costs in the range of 10% of $350,000, the investment of one dollar (doubled eight successive times) should pay for it all in eighty years, and it really doesn't have to pay for all of it, in order to be a big deal. A variation of this line of musing follows shortly, but it isn't an easy concept and must be studied to be understood.

Buying Out of Medicare. The other group who paradoxically often need the support of some sort of cost-shifting, are the elderly, among whom the variation in wealth is wide. It might appear otherwise because Lyndon Johnson took care of them with Medicare. Except he really didn't. The Medicare budget, according to its own reports, is supported in quarters: one quarter from payroll deductions from young workers, one quarter in premiums from the elderly themselves, and two quarters from general taxpayer funds, because it's a subsidized deficit. In this case, the "general taxpayer funds" are the pool, currently replenished by foreign borrowing, mostly from the Chinese. The voting public is shielded from this deficit at the moment, but this program is destined to suffer badly unless something is done. Politicians may tell you that tinkering with Medicare is the third rail of politics (touch it and you're dead), but alternatives would plainly be welcome. It is difficult for an average layman to obtain reliable data on government operations, and they are indeed quite bulky. Therefore, the amount of accumulated foreign debt attributable to Medicare is unclear, as is the yearly or current state of it. Nevertheless, the Medicare program might well be a bigger problem than Obamacare; it is certainly quite large. Putting a stop to further borrowing, not to mention paying off previous years' debt, would be a major achievement. Unacknowledged perhaps, but particularly welcome to elected politicians.

Someone just has to make the suggestion of making it possible for some people to buy their way out of the Medicare program. Don't gasp. Depending on what age was made eligible, and depending on the effective interest rate the HSA was able to earn, there are ways it might be possible to do it and save appreciable money. The ultimate goal would be to make the program self-sustaining, and to shift its costs from those in retirement to those still in the 21-66 age group, (plus the interest income on the residual buy-out fund during retirement). No group likes to have costs shifted to it, but as we mentioned, all revenue ultimately derives from the working age group. Aligning costs and revenue almost always clarifies and, for the most part, reduces the cost of any program, by reducing "moral hazard". For an idea like this, it makes it simpler to assume the HSA fund was earning income from birth to death at age 93. Some of this is double-counting because it is uncertain whether the future is a sole new program or if it is part of a cradle-to-grave project. It might start out as one, and evolve into the other. As a quick guess, either one might become feasible with the assumption that a voluntary program would have a gradual rather than abrupt rise in costs.

Other assumptions are: an average investment income of 5% net, for 93 years of life, and a steady inflation rate of 3%. We accept a lifetime medical cost of $350,000 and that Medicare will continue to be half of it. Let's take it in two steps. In order to cover a cost of $175,000 from age 66 to 93, an individual account with a net income of 5% must achieve a $90,000 escrowed balance by age 66. And, in order to have a balance of $90,000 at age 66, the individual must start with a "gift" of $4000 at birth. That is to say, an individual can buy his way out of Medicare for a single payment of $4000 at birth. That's not the exact story, but it establishes the framework.

The calculation assumes an individual will still pay half his costs, (one quarter as payroll deductions, and one quarter as premiums). Including the interest on these sums, the single-premium cost of buyout at birth would be reduced to either $3000 or $2000. Remember, the Government stops going deeper into debt, but the outstanding debt is unchanged. Let's call that a wash because a good deal is a good deal for everyone involved. Yes, the Government is losing the tax income from the individual's HSA tax deduction, but on the other hand, it doesn't have to keep paying so many administrators in Baltimore, on Social Security Boulevard.

Lifecycle Health Savings Accounts. So there's a plan for children, and another for the elderly. They consist of a Medicare buy-out, and an inheritance. Some of the latter derives from unused balances after the buy-out. For working people, there remain employer-sponsored plans, Obamacare, and Health Savings Accounts. Everybody's covered by one of these five variations, somehow. But let's explore going further in the opposite direction, by having a unified plan, cradle to grave. The superiority of one big unified plan over three smaller ones has yet to be demonstrated, and I would personally challenge anyone to defend taking such giant steps for no particularly good reason. That is, the default position is to reduce or eliminate cost-shifting, rather than add to it.

The final step would be to develop Lifecycle Health Savings Accounts, combining the gift from Grandpa, the Medicare buyout, and Health Savings Accounts -- all under one big tent. Some of that has been explored in a separate section, but what hasn't been defended is the advantage of doing it all at once, instead of step by step. As long as we are talking Blue Sky, let's explore the advantages and disadvantages of a unified Whole-life Insurance Company which even absorbed the functions of the Health Savings Account, internally, with a guaranteed rate of return. A century ago, some major companies devised this arrangement for life insurance, and I would advise talking to such companies to learn what they think of it. In short, you pay a regular premium, the company invests the premiums and waits for you to die. This proposal would then substitute a Health Savings Account for the death benefit, but why not, let's include that, too. In Sherman antitrust terms, that's called vertical integration, but vertical integration has now been deemed appropriate in the State Oil v. Kahn case. You'd probably find yourself in a tangle of state insurance regulations, administered by people untrained in all the added skills, but let's just say we found a reason to overcome such obstacles. Essentially, this proposal would be to transfer a group of quarreling government agencies from the public sector to the private one, using income guarantees instead of passive investing. The experience might resemble watching a train wreck, but perhaps it would demonstrate some overall advantages for the combination of conservative investors and adventuresome insurers.

Without stating a preference, that seems to be the range of possibilities.

Better, but More Complicated: Lifetime HSAs

Health Savings Accounts are a big improvement over traditional health insurance, and this book stands behind them -- as is, without major adjustments. Go ahead and get one right now, regardless of what other coverage you have. Let me repeat: Their secret "economy" lies in keeping everyone spending insurance money as carefully as he would spend his own -- but not being too dictatorial about it. No one washes a rental car, as the saying goes, so you can't act as if someone has committed a crime, just because he doesn't do everything for you. But just you let the individual keep what he saves, and millions of HSA owners will find ways by themselves to save up to 30% of traditional healthcare costs. HSAs provide an incentive for the medical consumer to shop more carefully, and consumers seem to respond. The difficulty is, some people are too sick to worry about rules. So, substitute a catastrophic high deductible for your present coverage if the law lets you do it (which is presently uncertain) but go ahead with a Health Savings Account and add to it when you can.

Looking ahead to what might follow HSA, is one of the main reasons for doing it.

|

One further simple idea: costs not prices. We have all assumed that catastrophic coverage is basic. If everybody ought to have something, he ought to have a very high deductible for a bare-bones indemnity policy. But just consider an addition: insurance for the health costs of the first year of life, plus the last year of life. That's technically simple to do retrospectively, although it takes most people a few moments to get it. And 100% of the population would receive both benefits, at a restrained cost by remaining uncertain just what the last year of life is until it is too late to run up its cost. Indeed, transition costs would be minimized by eliminating the historical part of costs for the transitioning population and phasing in the ongoing expense. Ask your friendly actuary; he'll get it, immediately.

Revised DRG coding and Methodology. Either way, if you guarantee to provide something for everyone, you better have a plan for controlling its boundaries. Inpatient costs affect patients too sick to argue about price, so hospital bed patients might as well be presented with some different options. They are more or less suitable for the DRG approach, but we have gone to some length to show what's wrong with the DRG coding methodology. The coding, among other things, must be fundamentally modified. As informed doctors will tell you, ICDA-11 isn't it.

DRGs ("Diagnosis Related Groups") is something Medicare started, which with more precise coding could be made ideal for the catastrophic insurance part of Health Savings Accounts. Medicare now contributes half of average hospital revenue, so its rules effectively dictate most other methods of hospital reimbursement. There are many problems with Medicare, but paradoxically, escalating inpatient cost is not one of them. Inpatient billing has been so muddled, most people do not realize that DRG has been a somewhat overly-effective rationing device. Like all rationing schemes, it causes shortages, as inpatient care is shifted toward the outpatient area. Office and hospital outpatient costs are quite another matter, so the whole hospital accounting system has been turned on its ear. In particular, components of inpatient costs must be re-linked to identical outpatient charges, in the instances where they are really market-based. Then, a system of relative values needs to be applied to that base. For that, we will need a Google-like search engine for translating the doctor's exact words into more precise code.

Single payer is not a solution, it is pouring gasoline on the flames.

|

Furthermore, both catastrophic insurance and last year of life insurance are more similar than they sound. What most people don't appreciate is the risk of a catastrophic health cost is rather remote in any given year. But in a whole lifetime, it is almost certain to happen at least once, which is often the last year of life. When you consider an entire lifetime, you cannot delude yourself it won't happen. Someone must plan for it, and the books must roughly balance.

Add Many Years to Lifetime Compound Income. Mathematically, it is fairly easy to show that healthcare costs will go down at the end of life; it's cheaper at 95 than at age 85. But that's probably a trick. We don't know what diseases will terminate life a century from now, so we can't count them. They are not cheaper, they are just unknown, and so we record the cost of the survivors of the race of life, not the average runner who will take time to catch up. If we are looking for lifetime healthcare revenue, recognize that practically all revenue is now generated by members of the working-age 21-66. A lifetime system needs to extend its revenue even further to other lifetime age groups. It seems only right that everyone's longevity should be included, but laws may currently block the way.

It would help a lot to include the first 21 years, adding several doubling-time periods. It would also be useful to let HSAs run for a full lifetime instead of mandatory rolling-over to IRAs at 66. Obviously, the idea behind terminating at age 66, was that Medicare would take care of everyone's medical needs. But with time, Medicare has consistently run big deficits, to the point where it is 50% subsidized by competition with other federal funds, or by international borrowing. Adding forty years would multiply extra investment returns by four doublings at 6%, and at little cost to the government. This would be particularly useful during the transition, when many people start their Accounts at zero balance, but at a more advanced age. It would be a significant improvement to all these programs to end them with at least one optional alternative; terminating a health program at a fixed age is something to avoid.

Proposal 13: Health Savings accounts should include the option to be individual rather than family-oriented, and therefore should include an option to extend from the cradle to the grave, rather than age 21-66, as at present, and consider options for Medicare buy-out and transfers within families between accounts.Permit Tax-free Inheritances of Funds Sufficient to Fund One Child's Healthcare to Age 21. In other words, we should make some sort of beginning to the knotty difficulty of making The State responsible for what used to be the family's responsibility. A second adjustment would recognize that essentially all children are dependent on their parents for healthcare support until they themselves start to work. Children's health costs are relatively modest, except for costs associated with the first year of life, and the bulge would be even greater if insurance shared obstetrical costs better between mother and infant. Even as we now calculate it, the baby's health costs, from birth to age 21, are 8% of lifetime costs. A cost of 3% for the first year of life alone, makes lifetime investment revenue essentially impossible for many young families to support lifetime costs because any balance would start from such a depleted level. So, the idea occurs that a considerable surplus appears when many people become older if grandpa could effectively roll over enough of his surplus to one grandchild or designee. The average American woman has 2.1 children, so it comes close to a 1:1 ratio of children to grandparents. Young parents often have a big problem financing children, whereas in a funded system, the transfer from grandparents could be supported by a fraction of it, by application of compound interest.

With two statutory adjustments along these lines, financing of lifetime healthcare by its investment revenue becomes considerably easier.

Whole-life Health Savings Accounts. (WL-HSA) It has developed in my mind that Lifetime Health Insurance would become even better for cost savings, with the addition of one more feature, copied from life insurance, and combined with the needed DRG revision. It is, broadly, the difference between one-year term life insurance, and whole-life insurance, which offers lifetime coverage as a variant of multi-year coverage. Life insurance agents frequently argue that whole-life is much cheaper in the long run than term life insurance. What they may not tell you is that most of the apparent profitability of term insurance derives from so many people dropping their policies without collecting any benefits at all. Comparing apples with apples, whole-life insurance is not just cheaper, but vastly cheaper.

For those who don't understand, one-year term insurance covers illnesses for a single year and then is open for renegotiation. By contrast, a whole life policy covers a lifetime of risk, overcharging young people for it in a certain sense, meanwhile investing the unused part for later years when health risks are greater. Does that start to sound familiar? The client is seemingly overcharged at first, but in the long run, his life insurance cost is far cheaper. Not just a little cheaper, but just a fraction of what a chain of yearly prices would cost.

It doesn't mean you must enroll at birth and remain insured until death; it means any multi-year insurance becomes cheaper, depending on the age you begin and the age you cash out -- often at death but not necessarily. What makes the saving so astonishing is the way life expectancy has lengthened. We have been so uneasy about rising medical costs we didn't much notice that people were living thirty years longer than in 1900. As a rule of thumb money earning 7% will double in ten years; in thirty years, it becomes eight times as big. If you lose half of it in a stock market crash, you still end up with four times as much. This is what would be new about lifetime accounts, and it can be easily shown that overall savings for everyone would be more than anyone is likely to guess.

Let me interject an answer before the question is asked. Why can't the government do the same thing? And the answer is, maybe they could, except two hundred years of history have shown the American public is extremely averse to letting anyone be both a player and an umpire. For more than a century at first, there was a strong political suspicion of the government running a bank, or even borrowing money with bond issues. Yes, the government could invest in businesses, but we would then be guaranteed a century of rebellion if we tried to have the government do, what any citizen is free to do on his own. Indeed, a review of Latin American history shows what disaster we have avoided by retaining this negative instinct to allowing the camel's nose under the tent. The separation of church and state is a similar example of how our success as a nation has been based on gut feelings. The separation of business and state is at least as fundamental as separating church and state. And for the same reason: we instinctively avoid having the umpire play on one of the teams.

Proposal 14: Congress should authorize a new, lifetime, version of Health Savings Accounts, which includes annual rollover of accounts from any age, from cradle to grave, and conversion to an IRA at optional termination. Investments in this account are subject to special rules, designed to produce a maximum safe passive total return, and limiting administrative overhead to a reasonable, competitive, amount. The account should be linked to a high-deductible catastrophic health insurance policy, with permanently guaranteed renewal, transferable at the client's annual option. The option should also be considered of linking the HSA to a policy for retrospective coverage of the first year of life and last year of life, combined. These two years are disproportionately expensive, and they affect 100% of the population. Subtracting their costs from catastrophic coverage should greatly reduce catastrophic premiums.

Lifetime Health Savings Accounts (L-HSA) would differ from ordinary C-HSA in two major ways, and the first is obvious from the name. In addition to meeting each medical cost as it comes along, or at most managing each year's health costs, the lifetime Health Savings Account would try to project whole lifetimes of medical costs and make much greater use of compound income on long-term invested reserves. The concept seeks new ways to finance the whole bundle more efficiently, and one of them is health expenses are increasingly crowded toward the end of life, preceded by many years of good health, which build up individually unused reserves and earn income on them. Since the expanded proposal requires major legislation to make it work, it must be presented here in concept form only, for Congress to think about and possibly modify extensively. This proposal does not claim to be ready for immediate implementation. It is presented here to promote the necessary legal (and attitudinal) changes first needed to implement its value. And frankly, a change this large in 18% of GDP is better phased in gradually, starting with those who are adventurous. By the time the timidest among us have joined up, the transition will have become routine. As a first step, let's add another proposal for the present Congress to consider:

Proposal 15. Tax-exempt Hospitals Should be Required to Accept the DRG method of payment for inpatients from any Insurer, although the age-adjusted rates should be negotiable based on a percentage surcharge to Medicare rates. The DRG should be gradually restructured, using a reduced SNOMED code instead of enlarged ICDA code, and intended to be used as a search engine on hospital computers rather than printed look-up books, except for very common hospital diagnoses. Also to be considered for those who are too sick for arms-length negotiation of hospital costs, are uniform reimbursements among insurance carriers and individuals, and between inpatients and outpatients, including emergency rooms, as well as a major expansion of specificity in DRGs.Overfunding and Pooling. Lifetime Health Savings Accounts, besides being multi-year rather than annual, are unique in a second way : they overfund their goal at first, counting on mid-course correctionsto whittle down toward the somewhat secondary goal of precision -- amounting to, "spending your last dime, on the last day of your life". To avoid surprising people with a funding shortfall after they retire, we encourage deliberate over-estimates, to be cut down later and any surplus eventually added to retirement income . For the same reason, it is important to have attractive ways for subscribers to spend surpluses, to blunt suspicions the surpluses might be confiscated if allowed to grow. An acknowledged goal of ending with more money than you need runs somewhat against public instincts and is only feasible if surpluses can be converted to pleasing alternatives.

Saving for yourself within individual accounts is more tolerable than saving for impersonal groups within pooled insurance categories, but probably must constantly defend itself against the administrative urge to pool. Pooling should only be permitted as a patient option, which creates an incentive to pay higher dividends for it. The menace of rising health cost at the end of life induces more tolerance of pooling in older people, whereas small early contributions compound more visibly if pooling is delayed. Young people must learn it gets cheaper if you don't spend it too soon. The overall design of Lifetime HSAs is to save more than seems needed, but provide generous alternative spending options, particularly the advantage of pooling later in life. Because it may be difficult to distinguish whether underfunded accounts were caused by bad luck or improvidence, the ability to "buy in" to a series of single-premium steps should both create penalties for tardy payment, as well as create incentive rewards for pooling them. This point should become clear after a few examples.

Smoothing Out the Curve.There is a considerable difference between individual bad luck with health costs and systematic mismatches between average costs of different age groups. Let's explain. An individual can have a bad auto accident and run up big bills; as much as possible, his age group should smooth out health costs by pooling within the age cohort to pay the bill. On the other hand, compound investment income sometimes favors one age group, while illnesses predominate in a different experience for another. It isn't bad luck which concentrates obstetrical and child care costs in a certain age range, it is biology. No amount of pooling within the age cohort can smooth out such a systemic cost bulge, so the reproductive age group will have to borrow money (collectively) from the non-reproductive ones. With a little thought, it can be seen that subsidies between age groups are actually more nearly fair, than subsidies based on marital status or gender preference, or even employers, who tend to hire different age groups in different industries. On the other hand, if interest-free borrowing between age cohorts is permitted, there must be some agency or special court to safeguard that particular feature from being gamed. All of these complexities are vexing because they introduce bureaucracy where none existed; it is simply a consequence of using individual ownership of accounts to attract deposits which nevertheless must occasionally be pooled later. Because these borrowings are mainly intended to smooth out awkward features of the plan, every effort should be made to avoid charging interest on these loans. However, if gaming of the system is part of the result, interest may have to be charged.Proposal 16: Where two groups (by age or other distinguishing features) can be identified as consistently in deficit or surplus -- internal borrowing at reduced rates may be permitted between such groups. Borrowing for other purposes (such as transition costs) shall be by issuing special purpose bonds. These bonds may also be used to make multi-year intra-family gifts, such as grandparents for grandchildren, or children for elderly parents.

Proposal 17: A reasonably small number of escrowed accounts within a funded account may be established for such purposes as may be necessary, particularly for transition and catastrophe funding. Where escrowed accounts are established, both parties to an agreement must sign, for the designation to be enforceable. (2606)Escrowed Subaccounts. Both Obamacare and Health Savings Accounts are presently expected to terminate when Medicare begins, at roughly age 65. Nevertheless, we are talking about lifetime coverage, where we have a rough calculation of the cost ($325,000) and the Medicare data is the most accurate set, against which to make validity comparisons. We want to start with $325,000 at the expected date of death, spend some of it in roughly 20 installments, and see how much is left for the earlier years of an average life. Then, we repeat the process in layers down to age 25 and hope the remainder comes out close to zero. There are several things missing from this, most notably how to get the money out of the fund, but let's start with this much, in isolation for the Medicare age bracket, age 65-85. We are going to assume a single-premium payment at age 65, which both life expectancy and inflation in the future will increase in a predictable manner, and changes in health and health care eventually reduce healthcare costs, not increase them. Not everyone would agree to the last assumption, but this is not the place to argue the point.

We know:

(a) The average cost of Medicare per year ($10,900)

(b) How many years the beneficiaries on average are in the age group (18).

(c) Therefore, we know how much of the $325,000 to set aside for Medicare ($196,200),

(d) And know how much a single premium at age 65 would have to be, in order to cover it. ($196,000 apiece)

(e) We thus know how much all the working-age groups (combined as age 25 to 65, 60% of the population) must set aside, in advance for their own health care costs, when they reach Medicare age ($196,000 apiece).

(f) And by subtraction therefore how much is left for personal healthcare within age 25 to 65 ($128,800).

(g)We can be pretty certain average Medicare costs will exceed those of anyone younger, setting a maximum cost for any age.

(h) All of this calculation ignores the payroll deductions for Medicare and premiums. Since this is nearly half of the cost, it changes the conclusions considerably, depending on how you treat these points. During the transition phase, several approaches may be necessary. Furthermore, the size of accumulated debt service is unknown, or what the alternative plans are, for it.

Shifts in the age composition of the population produce large changes in total national costs, but should by themselves not change average individual costs. What they will do is increase the proportion of the population on Medicare, thereby paradoxically making both Obamacare and Health Savings Accounts relatively less expensive. Obamacare can calculate its future costs with the information provided so far. But the Health Savings Account must still adjust its future costs downward for whatever income is produced by investments. We don't yet know how much each working person must contribute each year, because we haven't, up to this point, yet offered an assumption about the interest rate they must produce. We should construct a table of the outcome of what seem like reasonably possible income results. There are four relevant outcomes to consider at each level: the high, the low, and the average. Plus, a comparison with what Obamacare would cost. But there are two Medicare cost compartments: the cost from age 25 to 64, and the cost from 65-85 advancing slowly toward a future life expectancy of 91-93. These two calculations are necessary for displaying the relative costs of Medicare and also Obamacare.

Children's Healthcare. Someone is sure to notice the apportionment for children is based on income rather than expenses. The formula can be adjusted to make that true for any age bracket, and a political decision must be made about where to apply an assessment if income is inadequate; we made it, here. We have repeatedly emphasized that if investment income does not match the revenue requirement, at least it supplies more money that would be there without it. Somewhat to our surprise, it comes pretty close, and we have exhausted our ability to supply more. Any further shortfalls must be addressed by more conventional methods of cost-cutting, borrowing, or increased saving. In particular, attention is directed to the yearly deposit of $3300 from age 25-65, which is what the framers of the HSA enabling act set as a limit, somewhat arbitrarily.

Privatize Medicare? And finally but reluctantly, the figures include provision for phasing out Medicare, which everyone treats as a political third rail, untouchable. But gradually as I worked through this analysis, I came to the conclusion that uproar about medical costs would not likely come to an end until the Medicare deficit was somehow addressed. I believe we cannot keep increasing the proportion of the population on Medicare, paying for it with fifty-cent dollars, and pretending the problem does not exist. So it certainly is possible to balance these books by continuing our present approach to Medicare. But it would be a sad opportunity, lost.

In summary, we have concocted a guess of the outer limit of what the American public is willing to afford for lifetime health coverage ($3300 per person per year, from age 26 to 65), and added an estimate of compound income of 8% from passive investing, to derive an estimate of how much we can afford. From that, we subtract the cost of privatizing Medicare if our politicians have the courage for that ($98,000 -196,000) and thus derive an estimate of how much is available for health care of the rest of the population ($128,000). Because of the longer time spans available for compound income, at 8% it would cost more out-of-pocket to finance the $128,000 than the $196,000; it would actually be financially better to include it. The non-investment cost, on average, would only be $ 148,000 per lifetime, for an expense which otherwise almost insurmountably crowds out everything else in the national budget. It might be $98,000 less because of Medicare payments, or it might prove to be more, depending on interest rates and scientific progress. Believe it or not, that could be a wide improvement over the present trajectory.

That's how it seems at first when you approach the topic of multi-year health insurance. But there are several exciting additions when you really get into it. It plods along, and then it explodes.

Healthcare, A Much Simplified Overview

Let me say at the beginning, what could be repeated in a summary: The present healthcare dilemma has three interlocked parts, scientific, financial, and political. The scientific component is capsulized by three symbolic life expectancies: in 1900: age 47, today: age 83, and fifty years from now: age 100. We're living a lot longer, and soon expect the population to divide into thirds (one third getting educated, one third retired, and one third working to support the whole population. It probably won't work very well. Most health reforms amount to finding some way to shift income from the working third to the other two thirds.

The main scientific problem in the past was to avoid dying too young. But the problem in the far future will be living too long, running out of savings. Right now we can imagine having both problems, and few can guess which problem to fear. Maybe there is enough money for one of those two life terminations, but we don't have enough money for both of them, for everyone. We would have to give up something else, like national defense. Let's try to use the same money twice, if we can.

Finance. The payment systems need to be more interchangeable for alternative uses. But be careful. This could seemingly lead to merging Medicare and Social Security (someday) into one interchangeable program. Interchangeability of funds might plausibly seek to be at the family level instead of over-reaching to the level of demographic groups of whole thirds of the population. We do need to devise ways to transfer from one stage of a person's life to another, Saving for a Rainy Day, as it were. Some solutions will inevitably turn into problems. Proposals to integrate all health care into one vertical single-payer medical system would likely clash with more useful integration of Medicare and Social Security. These arguments can possibly wait for a later time, but only if we recognize they remain undecided. Generally speaking, they translate into recognizing that it is easier to shift money than people. Governments regard such as shifting with indifference, but we train children from birth to be possessive about their own money. And we elect politicians to see the difference.

Both the insurance spread-the-risk approach and the government pooling process skirt the difficulty there is not enough money to cover both possibilities for everyone. Either to borrow or insure postpones repayment for a while, that's about all. Meanwhile, healthcare costs are subject to more sudden changes in greater ranges than the economy as a whole.

Finally, let's see if we can put these shifts to work, and get some extra money from investment income, with compound interest working its magic over the whole expanse.

Politics. Meanwhile, we move toward a time when voters who earn money aren't sick, and the sick voters don't earn money. But they all have a vote. Already, we conduct transfers of money on a scale people may rebel against. It must become their own money, in their own accounts, spent later on themselves -- rather than forced transfers between demographic groups. At most, we might try extending that to the family unit, and even that should be kept as voluntary as possible.

Constitutional equal justice tends to make political solutions resemble one-size fits all.

|

So that's the general nature of our problems. Healthcare does become less expensive in the long run, even though more expensive in the short run. And through recent advances of financial management, Health Savings Accounts can generate surprising amounts of extra money on their own, overall helping with the other problems. The abstruse issue of inflation also arises here, where you might not expect it, because if trillions of dollars eventually migrate into passive investments through Health Savings Accounts, the elderly will hold shareholder voting rights they would be unwilling to surrender. The course of further inflation, the main concern of the elderly, would shift toward the hands of savers, away from borrowers. Unfortunately, what the proper balance is, isn't yet clear.

Flies in the Ointment

The reader will please excuse my round-about way of explaining the essence of an idea by skipping past one serious issue, and then returning to it. What you have just read is a succinct, perhaps overly succinct, description of the main elements of the lifetime HSA idea. Where I don't have precise data, I approximate it within the ballpark, assuming it can be sharpened up later. What has been deliberately omitted from the foregoing description, is the possibility that someone will get sick and spend some money. That's not just possible, it's certain. When you spend money on healthcare, you can replenish the fund, but you can't replace the income it would have earned if you hadn't spent it. You can slide past that difficulty by double-funding it, but then you would go to the other extreme and over-count it. The concepts involved are pretty simple, but the arithmetic gets pretty complicated because it will change over time. A monitoring agency must be charged with making objective annual mid-course corrections within boundaries set by Congress.

Double Counting.The lifetime Health Savings Account is in three parts: for children, for wage-earning years, and Medicare. For Medicare, the funding is fairly adequate, because the money is saved up in an escrow account, unspent while the buy-out price accumulates. In fact, it could be 50% over-accumulated by continuing the payroll deduction and premiums. Once you are ready to transfer the funds for the buy-out, you can decide whether you need to accumulate the payroll deductions and Medicare premiums. My guess is that at first, it would work without such supplements, but eventually, longevity would increase, new diseases and new treatments would appear, and risks of a cash shortage would then appear. Accordingly, continuing the payroll deduction and premiums would be one possible way to accumulate reserves for unexpectedly high sickness costs. If that method is chosen, some protections must be built in, to protect the reserve from being diverted to other uses..

The same might be true of Grandpa's grandchild insurance, which in a sense is borrowed from an adjustment in Medicare rates. The childhood costs are also fairly small. The only real example of double-counting which remains is in the wage-earning group from age 21 to 66. That issue could be visualized in two segments.

From age 21 to age 45, health costs of working people are not significantly higher than for children, except for obstetrics and gynecology. Even those two items are partly covered by splitting apart the obstetrical costs between mother and child, now artificially combined in contrived family insurance plans. Aside from this issue, the health costs of young adults are not greatly different from adolescent costs. From age 45 to 66, however, the cost curve gradually rises until older adult costs begin to match the Medicare costs (with terminal illness removed). It is this subset of one group which likely would create the greatest cost resulting in double-counting the investment income, and replacing the medical expenditures. Furthermore, this is also the arena of greatest cost-shifting, and therefore, may I say it, obscurity in the data. Nevertheless, the shortfall of middle-aged sickness costs has boundaries constraining it. The annual costs surely cannot be greater than the first year of Medicare, for example, and the earning power is at a peak at this time of life. The greatest medical advances have fortuitously concentrated in this group. The costs are likely to decline, as science concentrates on the four or five main diseases of maturity (diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer's, and Parkinsonism). There is also the special issue of the ability to delay some costs a few years until Medicare has the responsibility to pay for it.

It seems possible the data already exists to cope with the costs of these matters, but at an extreme, they should be covered by doubling premiums for the twenty years in question. Doubling $365 a year should provide a $365 cushion in escrow for contingencies. Since this is the peak earning period of life, and still remains well below average health insurance premiums, it seems to have the greatest fairness. Transition costs, the other great unknown, are beyond my capability to predict, and I simply don't do it. During the transition, the opportunity would exist to devote special research to this topic, and at least see if it turns up any crippling issues. I hope not, and I doubt it, but the potential has to be acknowledged. In the meantime, it would look as though the good ol' standard issue Health Savings Account is a little safer bet. It reduces costs, but not as much as the various methods of capturing the upswing of compound interest, at its far end.

Black Swans. There's a possibility that things will go in quite the opposite direction. The stock market has been going up at a rate of 12% for a century. Why does the investor only get 5% to spend? Inflation is clear enough, but why not 9%? In a sense, this apportionment is traditional, tracing back to investing endowments for colleges or museums. If the stock market has a black swan and drops 50%, are you going to close the doors of the college until the market recovers? One conceivable strategy for this event would be to accumulate a cash reserve to be used during the dark days of depression. However, this has inflation dangers, and it is impossible to say how much it should be because if you keep 50% in reserve, you might as well say you are only realizing 6% overall during a 12% rise. So, the alternative wisdom urges an investment of 60% in stocks (at 12%) and 40% in bonds (at 4.5%), allowing you to keep the doors of the college open in both an inflation and deflation when the numbers will suddenly change. So, a 60/40 investment ratio became traditional in investment circles, reinforced by saving the neck of many investment managers. But just a minute.

We are investing in our own health care, not for a college. If revenue declines for several years, it doesn't matter nearly so much for a young person if his income dips, only to recover in later years. The fundamental argument underpinning 60/40 is weakened considerably. If the market is headed for 12% in the long run, why not just ride out the dips and peaks? There's no good reply to this challenge, except an innate conservatism when you are managing other people's money. Very well, why don't we just lean in that direction? Surely a ten-year-old child can ride it out, even if a 70-year-old has to be more cautious. Consequently, you begin to see more and more investment managers leaning toward 80/20 or even 90/10 mixture of stocks (12%) and bonds (4%). When your clientele is of many mixed ages, such as pooled Health Savings Accounts are likely to be, perhaps the younger ones would be well served to get 6% or 7% income, while the older ones play it safe with 4%. This line of reasoning is likely to be more widely heard as uncertainty about middle-man costs gets more wide-spread. If the investment manager is suspected of taking 2-3% of the reserve as a kick-back, or just profit margin, it becomes a more pointed argument that brokerage accounts are not pooled investment funds at all, but rather an open market between a buyer and a seller. If the stock market takes a black swan dive, you can be sure the 4% reserve will not be used to buffer the losses of the investor, in the present arrangement of things.

If the projected investment return is high enough, no investment contingency is worth discussing. In this book, we only wish to point out that a 6.5% lifetime return is more than ample to cover lifetime health costs, plus a wide contingency reserve. That is particularly true if you remember the bulk of costs come later in life. A return of 6.5% does not seem at all inconceivable, if you look at Ibbotson's data for Twentieth-century asset returns, and read John Bogle's books on saving passive transaction costs on total-market index funds. At the same time, I am mindful of all those potentates who blithely accepted 17% projected returns on pension funds a few years ago, and now look at them. We are double-counting the reduced medical costs of the future, which we cannot know with precision, and warn that you must keep an eye on them. But there is such a wide swing between present premiums and any conceivable escalation of $365 a year, that it seems worthy of serious investigation.

The Premium of Catastrophic Coverage. You have to feel sorry for the owners of an insurance company which sells catastrophic health insurance. It has long been defined as high-deductible coverage, but nowadays everything has a high deductible and an upper benefit level which is not mentioned much. The was a time when a well-functioning market was maintained by the adage that the higher the deductible, the lower the premium. It was often called "Excess major medical coverage", and entirely used as reinsurance. Under the circumstances of the Affordable Care Act, high deductible policies hide the subsidies they make and receive and do their best to avoid quoting a price unless the customer is in the office and has his pen in his hand. The Affordable Care Act made it clear it would like nothing better than to have Catastrophic insurance disappear in disgrace. As a matter of fact, ever since the McCarran Fergusson Act, it is a question whether any insurance may be regulated under the Federal, as opposed to State, government. The United States Supreme Court has an opportunity to address these vexing issues in King v. Burwell , and we await its decision with eagerness.

Spending Rules--Same Purpose As Escrow Accounts

Useful features are buried in the spending-rule idea. A portfolio would never go to zero if spending is held below a certain level; an endowment on auto-pilot. This magic number was once 3%, now is thought to be 4%. In trust funds for irresponsible "trust fund babies", spending rules are particularly common. In taxable circumstances, it is a vexing complication for non-profit institutions that federal tax rules require minimum annual distributions of 5%, somewhat more than a taxable account can sustain indefinitely, at least according to present theory, and assuming present costs. Every effort should be made to reduce middle-man costs, and the present rate of progress is encouraging. As long as medical progress continues to depend on a top level of talent, efforts to attack the cost of care itself may prove counter-productive.

In my opinion, a spending rule is pretty much the same as a budget, and the same goals can be accomplished with an escrow account, permitting no expenditures at all until a certain date, and then only for a stated purpose. And furthermore, there can be several spending rules, just as there are several lines in a budget. There surely ought to be both a discretionary spending rule and an inflation spending rule, for example, since inflation is beyond citizen control. As a practical matter, planning will generally mean 5% discretionary, and 3% inflation, for a total of 8%. Until recently, it was generally assumed if the Federal Reserve instituted, or Congress mandated, an inflation target of 2%, it would mean 2% was dependable because the Fed had unlimited power to print money. However, in 2015 the inflation rate is 1.5%, in spite of heroic efforts to use "Quantitative Easing" to bring it to 2% by buying two or more trillion dollars worth of bonds. Inflation has remained at 1.5%, resulting in much wringing of hands. So spending rules help establish responsibility for deviations.

It is not useful to engage in political arguments over why this is so, it must be adjusted for. The consequence is we have an Inflation Spending Rule of 3% and actual inflation of 1.5%, leading to a national inflation surplus of 1.5%. If a Health Savings Account has an Inflation Spending Rule of 3% only because that is what we have seen in the past century, our inflation is 1.5% under budget, which could easily be misinterpreted as an extra 1.5% to spend. When we figure out what this means, we can puzzle what to do with it, but until that happens, no spending allowed. Another precaution would be to have two spending rules, totaling 8%, only 5% of which is actually spendable. If we create special escrow funds for buying out Medicare or passing to our grandchildren -- the same thing.

If you don't limit yourself, Others will limit you.

|

| Spending Rules |

In the case of Health Savings Accounts, a spending rule of 6.5% within an investment yielding a net of 9%, is a special case, but a good one. The central purpose of the whole HSA idea is to lower the effective cost of medical care, by generating funds to pay for it. The more income generated, the lower the effective price of medical care, so why impose a spending rule? In fact, a spending rule for an HSA does not reduce the income, it only delays the spending of it, because either the funding account gets exhausted by the time of death, or it is rolled over into an IRA. Either way, there is no final end to HSA spending, only postponements. When spending is postponed, it eventually earns more income; the ultimate effect is more availability for health care. If a cash shortage forces the HSA to curtail health spending, the bills must be paid from other sources, usually taxable ones. So even in this situation, there is more health spending power ultimately generated, but it is generated by not spending tax-sheltered money. It could even be argued that diseases later in life tend to be more serious. Indeed, if a spending rule is under consideration for an HSA, it could be voluntary as long as there is no way to game it. Unfortunately, that can lead to coercion for someone's own good, always a dubious idea.

If a portfolio generates 8% but only spends 5%, there's a safety factor of 3%, almost exactly matching the long-term effect of inflation. We hope moreover, the inflation issue is addressed by using the theory that inflation of expenses should match inflation of revenue, but you never can be sure of it. It is, in fact, more likely they won't match. A spending rule increases the power to shift surplus revenue to years of high medical cost, which will be later years, and will, by compounding, actually increase the total amount of it. This consequence is not necessarily obvious. The spending rule guards another easily forgotten thought: the purpose of an HSA is not to pay for every cent of health care. It is meant to pay for as much of it, as it can. It is likely, to invent an example, to encourage skipping cosmetic surgery, so there will be money enough for cancer surgery at a later time.

The purpose of this soliloquy is to justify the establishment of escrow accounts within Savings Accounts, to keep the fund from wandering from its purposes, or at least to recognize it early if it does. There should be a Medicare buy-out escrow fund, with a suggested budget calculated to make it come out right. And a Grandparent's escrow fund, and Permanent Investment Escrow fund, budgeted to pay for a future lifetime of care, alerting the owner how much it is below budget. These escrow funds are intended to be flexible but intended to serve their purpose. HSA Account managers are encouraged to use them and to explain them. By making certain escrows mandatory and uniform, big data monitoring is facilitated. Other government access should be minimized.

Escrow Accounts for Future Needs.

One of the important advantages of Health Savings Accounts over historical health insurance lies in the contrasting sacrifices you must make if you can't afford everything. Traditional health insurance ("first dollar coverage") paid for the small things, but if you ran out of money, you had to sacrifice some big things. The Health Savings approach is to provide money for the big things first and sacrifice little things if you must. That's the essential philosophy, and it has become exaggerated by increased longevity. We need to add a simple way to by-pass small expenses and save money for later. That's the reasoning behind adding escrow accounts to high-deductible insurance.

Think about it: when a subscriber faces a medical expense costing more than his account balance, he has three choices. He could forego the medical service, he could pay cash out of pocket, or he could borrow the money. Sometimes he will have enough money in the account, but saves it for some later purpose; in that case, he might be both a borrower and an investor at the same time. When it comes time to pay off his loans, that obligation should have a higher priority than investing new money, since otherwise, the subscriber is investing on margin. Margin investing is generally a bad idea, but it can be made less risky through using an escrow account. That's a designated-purpose account, which is more difficult to invade. So, he may divide his account into three escrow accounts, and the managers may decide they need even more. It becomes inflexible if it can never be invaded, but it shouldn't be easy and paying cash or tax-unsheltered money is always better if you can.

Borrowing Escrow. It's wise to pay off debts early, so the program should require its permission to do anything else with a new deposit. Not all managers of HSA will advance overdrafts, but some will, probably at rather high-interest rates. More commonly other subscribers will have surplus money they would like to lend like a credit union, because deposits up to their annual limit are tax deductible, and they would be reluctant to pay the taxes to redeem them.

If you will need it later, Set it Aside, Now.

|

| Escrow Subaccounts |

It's possible to imagine gaming such arrangements of differing tax liability, so Congress must decide what circumstances permit it. With insurance, considerable pooling of resources happens without tax consequences, but when bank accounts are individually owned, pooling is not allowed without legal provision. Depositing unencumbered money in the escrow account is the same as investing it, except its presence indicates availability for loans in certain circumstances. Nevertheless, it is inevitable that gaps between the two curves, revenue, and expense, will develop, even though the hills eventually exceed the valleys.

My suggestion is to limit structural borrowing at low-interest rates to smoothing out the valleys characteristic of entire age levels, rather than provide individual banking arrangements between subscribers. Over time, these variations will standardize. And since the accounts will collectively grow, the quirks will eventually stabilize the investment accounts, possibly even augmenting income. However, if a surplus or deficit is exhausted, it should not be perpetuated with outside financing. The accounts operate under the principle that they come out right at the end. It, therefore, ought to be possible to adjust age-determined structural imbalances in bulk, while attempts by subscribers to game such variations should be countered by modifying interest rates.Wholesale buyouts have their advantages, but piecemeal buy-outs are better.

Proposal 5: Congress is urged to permit pooling (at low interest) between the accounts of an age group inconsistent surplus, -- and other age groups in consistently deficit status,-- occasioned by persistent divergences between revenue and medical withdrawals at differing ages. If there are other imbalances created by differential depositing, they should be corrected by adjusting internal interest rates. (2735)Medicare Escrow. There are a number of reasons why some people would want to buy their way out of Medicare, whereas others would become terrified at any mention of changes in their Medicare plan. The incentive for the government to permit Medicare buy-outs would lie in ridding itself of its deficit financing, with secondary borrowing from foreign nations. And the advantage for the plan itself is providing a cushion for a transition to lifetime accounts, ultimately a better cushion for revenue misjudgments.

By noting the average annual cost of Medicare, the number of Medicare beneficiaries, and the average longevity of subscribers, the average lifetime Medicare costs of Medicare can be calculated. Assuming inflation to affect both revenue and healthcare expenses equally, inflation is ignored. Then, with various compound investment assumptions, a range of future income can be estimated. All of this can be estimated as requiring a lump-sum payment of $60,000 at the 65th birthday in order to make a fair exchange for the Medicare entitlement and guessed at $80,000 if accrued debts are serviced. However, the individual would have paid about half of that with previous payroll deductions during his working life (a quarter of the total), and by buying out of it at age 65, would be relieved of Medicare premiums which amount to another half of what is left, or a quarter of the total cost. However, that complexity of description eventually leaves half of the total to be made up by Federal subsidy from the taxpayers because loans must be repaid. It's complicated because every revenue source available has been tapped.

The biggest issue is a foreign debt to be paid back for financing Medicare deficits in past years. Consequently, in order to put a stop to further borrowing, the buyout price must be raised. Obviously, if a past debt is serviced, more contribution is needed. Unfortunately, information about prior indebtedness is not readily available, so the entirety is here guessed to require a single-payment premium of $80,000 at the 65th birthday, for a full Medicare buyout. If the entire Medicare program, past and present, is to be paid off, they're very likely will have to be a tradeoff between increased revenue from HSA deposits and diminished service of foreign debts. As a guess, the elasticity of HSA revenue of $3350 per year, from age 26 to 66, has already more than reached its limit. For the moment, we have accepted the present Congressional limit, which was presumably rather arbitrary. While it is possible to imagine this arbitrary limit could be made to stretch to cover lifetime health costs, more likely it will only cover a portion. But to cover the Medicare unfunded debts of half the past century in addition to current costs, will require some new concept, as yet undevised, and a good deal more information than is presently public.

"All-other" Escrow. It is difficult to foresee which escrows will prove so popular they will require limits, and which others will be so unattractive they will require minimums. Moreover, it can be anticipated some people will wish to use account surplus as an estate-planning tool, while others will have no estate. A provision in law directing the uses of account surplus at death may thus appeal to the majority of subscribers, but actually may be highly unsuitable for the majority. Therefore, while it seems harmless to provide a vehicle for such individualization, too much should not be expected of it.

To most readers, these sums will seem prodigious, and indeed they are. Few people at present are in a position to consider them. We can pray for some relief from scientists, from the economy, and from demographics, because downsizing Medicare is a growing requirement, provoking even more drastic remedies if we sweep it under the rug. We need, first, to make Medicare more modular so it can be downsized in pieces, instead of all-or-none. In time, we need to downsize it and use the pieces to fund protracted retirement costs. The long-term goal, for the scientists, the politicians, and the patients, is to make it unnecessary to spend so much money on health. Beyond that, the funding of retirement has no logical limit. This long-term vision of our future must first become commonplace in our culture so we will seize every chance opportunity to advance it in fact.

Using Escrows to Estimate Cost Risks(1)

The general thesis of this proposal is we can make better guesses about the future than we think we can, just as long as we remain aware they are guesses. In the past, that approach has made some blunders, like the sun revolving around the earth, or Columbus badly underestimating the width of the oceans. And so the world divides itself into "failure-avoiders" and "success-seekers", each contemptuous of the other. Those divisions are not likely to change much.

The proposed approach is to estimate how much we must save to achieve a distant goal, subtract it from the amount we can stretch ourselves to save, and see if what's left, is a realistic number. If you envision atom bomb attacks and climate catastrophes, the answer is No. But if you confine yourself to the question at hand, the answer might well be Yes. So as long as we confine ourselves to a voluntary approach, the nation will hold itself together if someone is wrong.

Let us repeat the basic assumption, that for practical purposes, all money is derived from the working age group, 21-66, and everything else is essentially borrowed. That is, the health costs of children under age 21 are supported by their parents, and those over 66, by savings. In addition to this basic division, about 10% of the population are unable to support themselves because of disabilities, prison and related matters--and must be subsidized. All of these side issues are slowly improving, but in this analysis we must ignore them, or at least treat them as a general category. We are now about to consolidate children and elderly people into one group.

That is made possible by the happenstance that our birthrate is 2.1 children per mother, which comes out to be one grandparent per grandchild. There are all manner of exceptions, like trans-gender people, divorces, polygamy and what have you. Our purpose is not to be comprehensively respectful, but to estimate quantities. And one grandchild per grandparent suffices for that. If each grandparent is financially linked to one grandchild, the others are a matter of pooling more with less. All newborn health costs are the responsibility of someone else, usually the father, increasingly the mother. This proposal suggests that we make health costs the responsibility of the grandparent generation, since Medicare has already made the grandparents the responsibility of government. We do this because Medicare is increasingly becoming a burden we cannot sustain. The public does not seem willing to listen to this, and so politicians are unwilling to bring it up. But Medicare is unsustainable in its present form, and therefore is absolutely destined to change. When we eventually face facts, I believe it will seem rational to combine the health costs of the two groups, so I propose we start the ball rolling by taking advantage of it sooner rather than too late. We can come back to this later, but let me briefly step up to the soap box:

We are launched on a demonstration model to the effect that compound interest income can greatly reduce the effective cost of healthcare. It is the nature of compound interest curve to turn upward the longer they extend. Therefore, we would greatly enjoy substituting lifetime compounding for annual premiums, and the greater the longevity the better. However, lifetime healthcare funding is greatly hampered by the rather high costs of the first year of life. People would almost have to live to be two hundred years old to make up for that high cost at the beginning of life, would have to inherit several thousand dollars, and would have to have rich parents instead of nearly insolvent ones. It is almost impossible to overstate the hampering effect of the high costs of the first year of life. So, we propose that grandpa transfer some of his excess Medicare funds to a grandchild, overfund Medicare a little to make room for the cost, and use Health Savings Account transfers as the vehicle for it. That adds at least 21 years to the compounding of 21 to 66, and it could potentially add the years 66 to 83, our present life expectancy. If we can somehow transform 44 years of compounding to a full 83 years, the financial consequence would be astounding. We are talking about lifetime health care, supported by a third of a lifetime of savings, if that much. No wonder the actuaries are wringing their hands.

Using Escrow to Estimate Health Costs (2)

Because so many people's circumstances are so different, we offer two ways for Grandpa to transfer one grandchild's health care to one grandchild, and skip any description of pooled transfers of the rest.

Grandpa can either transfer a lump sum single-payment upon the birth of the lucky grandchild or through his will if that is more suitable. Alternatively, the Health Savings Account of one generation can transfer $365 yearly to the grandchild's escrow account, which is set aside for grandchild to buy his way out of Medicare -- if he later chooses -- at the 66th birthday. Grandpa will only do this for 21 years, after which it is the child's own responsibility. According to my math, that will pay for the estimated costs of Medicare, stop the foreign borrowing to pay for deficits, and perhaps make a dent in the accumulated foreign debts.

What it won't do is pay for the grandchild's health costs if they escalate out of control between now and then, or if Medicare is forced to add on all manner of deductibles, copayments, taxes and other out-of-pocket exceptions to pay for cost escalation. His catastrophic health insurance is supposed to protect against that, and within limits, it will. But at the present time, catastrophic health insurance has been so jumbled that you cannot get a salesman to make an average quote for publication. It will only become possible to make sensible judgments after the United States Supreme Court has made a final judgment, or if Congress assembles a sufficient majority to clarify the situation. As matters stand right now, there is no need for excess coverage, and the money in the escrow account should be released to an Individual Retirement Account (IRA). The amounts of accumulated funds in HSAs are illustrated in accompanying tables, grouped in multiples of $365 contributions. For very high-cost over-runs, catastrophic health insurance would normally be an alternative to consider.

But that -- encompassing childhood costs and Medicare buy-out -- is only half of the proposal. The rest has to do with the age group 21-66, which is now tangled in the courts, under King v. Burwell and I cannot go further.

Lifetime Health Insurance: Monitoring the Data

The longer we wait to make drastic changes, the more difficult they become, more proof of benefit will be demanded. In the proposed case of switching health insurance from term insurance to whole-life, a century of insurance development contributed insights. But remember, the past fifty years have seen plenty of dissatisfaction come to the surface, only to be dashed by a (generally correct) opinion that the old system was working better than the proposed one would.

Health Cost Monitor Center. This time, let's start in advance with establishing a monitor center, and locate it near other public data centers. Turf issues are inevitable, but bowling teams can break them down. With attention to the issue, an interagency technical center could develop into a useful employment center, attracting superior people with vastly enhanced opportunities for personal advancement. If the center is large enough and sufficiently diversified, it will resist abuse by tyrants.

By waiting fifty years, we now have big data. But we could have had answers, fifty years ago.

|

| Perfect is the Enemy of Good Enough |

Conversely, in a population as large as ours, enough people of younger ages will inquiring minds; the problem is to establish the right leadership, and the right opportunity so we can still estimate in advance what difference our proposals make to costs at almost any age. At least then, the public could judge what is actually happening, instead of relying on the pronouncements of political candidates. Half of hospital cost experience already resides in Medicare data, the last years of life are well documented, and the first years of life are fairly predictable for these purposes. So we start the data with pretty good anchors and a panoramic overview of costs. With at least a stated goal of offering suggested prices for lifetime planning, but not necessarily universal ones, we should be able to cope with a voluntary system.

Footnote: An experience forty years ago makes me quite serious about this monitoring issue. While I was on another mission, I discovered Medicare and Social Security are on the same campus in Baltimore, with their computers a hundred yards apart. So I proposed to the chief statistician, that the Medicare computers already contained the date and coded diagnosis of every Medicare recipient who had, let's say, a particular operation for particular cancer. At the same time and in the same location, the Social Security computers contain the date of everybody's death; the Social Security number links the two. So, why not merge one data set into the other, and produce a running report of how long people seem to be living, on average, after receiving a particular treatment or operation -- and how it seems to be changing, over time. (Length of survival = date of death minus date of the procedure) He merely smiled at the suggestion, and I correctly surmised he had no intention of going any further with it. This time, I resolved to write a book, to see if that might have more effect.

Let's ponder about some of the uncertainties which can only result in guesses at the moment, but which in time can be more precise, and provide the material for mid-course corrections:

Considering the sums involved, We don't watch public money very carefully.

|

| You Cannot Have Too Much Data |

Transition Calculations. Let's say we have politicians with the skill to persuade the public to phase out Medicare in order to put an end to the foreign borrowing of half its costs and persuade enough beneficiaries to do so by buying themselves out of the program. It has been our extrapolation that this could be done with a single payment of $80,000 at age 66, having earned an income of 6% since age 30. The cost would compare favorably with present payroll deductions for Medicare, although of course, you can't spend it on two different things; the present premium costs of Medicare provide a roughly equal amount. That provides a price goal, for the beneficiary to make a last-minute decision whether to go ahead with the buy-out. And during the years of accumulating the wherewithal in an escrow fund, it presents a distant steady goal. In addition, we also must recognize that a large foreign debt has been obligated to pay for shortfalls of years now past.

The size of the debt is unclear, but we estimate about an additional $80,000 would pay it off. If the numbers come out wrong, the debt payment could be shrugged off, the way the Chinese Imperial government did a century ago, and the way the Greek government wants to do at present. For argument sake, let us assume that debt to be $80,000, but we are unsure how to pay it. (If I sound like Lyndon Johnson, it is because I am dealing with the same topic.) If these numbers approach any kind of accuracy, the process of buy-out could begin, voluntarily, delaying the choice until the 66th birthday. If there is significant interest in the idea, these numbers could be sharpened, but there would always remain some guesswork. Some additional protection of the gamble could be provided by adding a catastrophic insurance policy. In the long run, this whole buy-out idea would be strengthened by migrating the center of care to a nearby retirement village and using the hospital system only for tertiary care. Obviously, it is intended that the proposed monitoring center would be actively involved, and not merely act passively collecting data without designing some large-scale experiments, also obviously voluntary.