3 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

Philadelphia Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began about the time America declared Independence. The young nation faced a clean slate and boundless opportunities.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Musical Philadelphia

Quakers never cared much for music, but the city has nonetheless musically flourished into international fame. At the same time, quarrels and internal battles have also been world class.

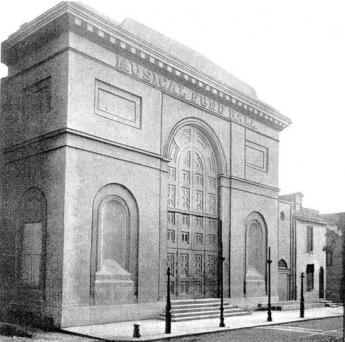

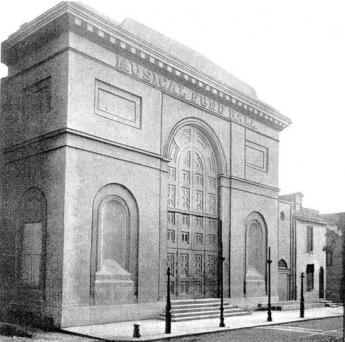

Musical Fund Hall

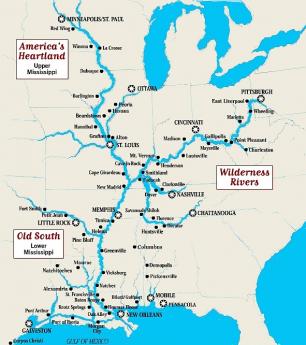

|

| William Strickland |

At the corner of 808 Locust stands a condominium building with a colorful history. It was originally the First Presbyterian Church, and then in 1820 the famous architect William Strickland converted it into the largest musical auditorium in the City. For several years, a group of music lovers had been meeting to discuss the problem of aging and retired musicians, most of them impoverished. The idea arose of giving several benefit performances each year to raise money for retired musicians, and the idea was enlarged to create a Musical Fund Society to put on regular concert series. Since it was by far the largest public auditorium, it also served for graduations, speeches, conventions.

|

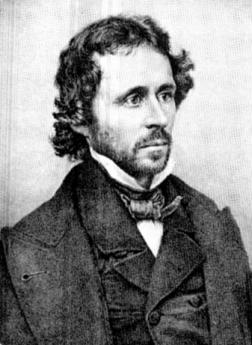

| John C. Fremont |

It thus came about that in 1856 the Republican Party held its first national convention there, nominating for President John C. Fremont, the famous explorer of the West. The Republicans had two main components, the advocates of the abolition of slavery, and the residual of the Whig Party, which had come apart. The Whigs were mainly concerned with using government effort to promote the economy, building canals and roads, and similar ideas for public benefit. Abraham Lincoln had been a fervent Whig.

|

| Musical Fund Hall |

As a musical society, the Musical Fund was quite instrumental in persuading this Quaker City that music could be used for purposes other than religious incantations and frivolous entertainments. And it was useful in bringing the new instruments and musical concepts from Europe to the New World. Louis Madeira has written an interesting history of the early musical significance of the Musical Fund. When the Academy of Music opened in 1856, the old hall on Locust Street became a relic of the past. It had assets, however, and the organization continues to function as a granting agency for musical production and development in the Philadelphia area, even though it is itself no longer in the business of musical production.

And then the third strain of history in this old place is the development of Musical Unions. This is natural enough, in view of the original purpose of helping indigent musicians. But unfortunately, several competing unions appeared, most of them on Locust Street and the dissention was bitter and continuing. In 1871 Philadelphia was the scene of the creation of the National Musical Association, and although the local 77 became a part of the national movement, it was stormy. Competitive musical unions had a history of calling the police to shut down speakeasies run as private clubs by their competitors. During the Depression of the 1930's there were many accusations of Communist infiltration, and counter accusations that Joseph Petrillo, the national president, was a Nazi. An underlying theme among musicians was that foreign immigrants were willing to work for less than the standard wage, and hence many of the coercive features of the union were aimed at forcing immigrant musicians to become members and to refuse to work for substandard pay.

Some idea of the bitterness in the situation can be gained from the strike against the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1956. Ten years later, only one member of the union in ten was employed.

REFERENCES

| Music in Philadelphia: and the Musical Fund Society, Louis C. Madeira ISBN: 1-932109-44-7 | Ross and Perry Inc. |

| Musical Notes of a Physican: F. William Sunderman Sr. ISBN 0963292706 | Alibris |

Mummer's Strut

|

| Mummers |

For over a century, and maybe for two centuries, the Mummers Parade has strutted around Philadelphia on New Year's day. The Mummers have lots of tradition and oral history, but the authenticity of records going back to the early days of the parade do not meet very strict standards. There are those who say that the earliest mummers were "shooters" who coursed through town on the Fourth of July, shooting pistols in the air with one hand and carrying a bottle of booze in the other. Booze, by the way, was the name of a bottle manufacturer which became associated in common parlance around 1840 with the product most commonly found in the bottle. The name booze bottle was attached to a bottle in the shape of a log cabin, suggesting a possible link to the 1840 Presidential election of William Henry Harrison, Old Tippecanoe. The other historical origin was thought to be the annual parade of the guilds, the butchers, carpenters and similar. Somehow, these two traditions came together in the annual parade on New Year's day, with various ethnic clubs spending all year getting ready to compete with each other for attention. Many of the floats are reminiscent of the New Orleans Mardi Gras parade, some cubs specialize as "comics" in the style of the old shooters dressed up as clowns. The increasingly dominant part of the parade is found in the ten or twelve String Bands.

|

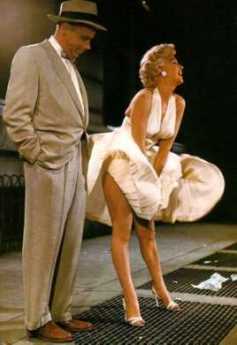

| Marilyn Monroe Effect |

The main instruments of the String band are the banjo, with the tune carried by some saxophones and a peculiar instrument that looks like a xylophone held up on a pole. emitting an octave of piercing chimes.The old favorites are "Dem Golden Slippers" "Wait 'till the Sun Shines Nellie" and similar fast marches. The costumes tend toward ostrich feathers and gaudy colors, and in recent years the string bands all put on a little show or dance in front of the judging stands. Since it takes place in January, it is usually quite cold at a Mummer's parade, and since the parade goes along streets lined with tall buildings, the wind builds up quite a"Marilyn Monroe Effect". Until recent years, the mummers have always been male.

The mandatory traditional food at a mummers parade is a Philadelphia soft pretzel, smeared with mustard, sold by street vendors. Hot dogs, American flags, and soft drinks are for sale, as well, and other beverages are provided by the onlookers themselves. The parade itself is only an annual public display for the mummer's clubs that have traditionally met weekly in the ethnic neighborhoods, arguing hotly about next year's costume (a deep secret until the day itself), drinking, dancing and sewing the costumes, rehearsing the tunes and the dance steps. There is a traditional "Mummer's Strut, in which the participants and many onlookers participate spontaneously. In its fullest expression, the mummer will hold an umbrella in one hand while holding forward the lapels of his jacket with the other hand, bending forward at the waist, throwing back the head, and more or less keeping time with the music., and shaking the umbrella at the cheering crowd. There's a museum devoted to this sport, located on Second Street, otherwise known as "Two Street". It's all lots of fun, but it is usually too blamed cold to stay there long, and most people eventually retreat to a nearby television to watch the rest of it In the days when the parade went up Broad Street, it passed the Union League where another New Year's tradition was in progress, with the Republican members eating terrapin and drinking Fish House punch, quite comfortable in their warm quarters looking out of bay windows. Democratic Mayor Rizzo used to march in the parade, and when he passed the League, would ostentatiously turn his head away from it. Subsequent Democratic mayors have been even more polarized; the parade now goes up Market Street.

Early Germantown-Music

|

| German Brass Band |

What we now call Germany was a collection of small principalities until Bismarck unified the country in the Nineteenth Century. That probably accounts for the several different traditions of German Music, ranging from Oom-pa-pa brass bands to Wagnerian Opera. In addition, there were several waves of German immigration into Pennsylvania, each one of which had its favorite musical style of the moment, which then persisted as a tradition in some pocket of immigrant descendants. Germans in Germany would, therefore, relate a somewhat different history of musical evolution than Americans of German descent would recognize.

The intellectual German Quakers who settled into Germantown in the Seventeenth Century were highly musical, while the English Quakers down the hill in Philadelphia distinctly were not musical at all. There was a central musical feature to the Germantown hermit monks under Johannes Kelpius, their leader, who was a musician of some note. The printing and publishing houses of Germantown spread this music up and down the inland valleys of the Atlantic Coast region so that even after Germantown itself ceased to be the cultural center of things, the Ephrata Cloister carried on. The present center of 18th Century German music is now in the Lehigh Valley. Although Johann Sebastian Bach had been dead for a hundred fifty years before it was founded, the Bach Choir of Bethlehem now conducts the oldest continuous Bach Festival in existence. It's well worth the short trip to Bethlehem if you can get tickets, and more importantly, if you can find a place nearby to park.

German Origins of the Philadelphia Orchestra

|

| academy of music |

The histories of the Academy of Music and the Philadelphia Orchestra are distinct but intertwined. At the moment, the Orchestra owns the Academy, but it was not always so. The Academy of Music of Philadelphia was built in 1857, but the Philadelphia Orchestra was not founded until 1900, just for instance.

It is undeniable however that Philadelphia orchestral music began its present direction with the German immigration wave of 1848, bringing with it the new musical concepts of Felix Mendelssohn. Except for the wedding march which has sent innumerable brides down the aisle, most people now have a little trouble naming a piece of music written by this composer, but in fact, he produced twenty to fifty pieces a year from 1820 to 1847. In terms of pure virtuosity, Mendelssohn was probably the most prolific and gifted composer after Mozart. His lack of really notable productions has sometimes been attributed to his wealthy childhood and too-easy success, but in his day he was nonetheless a musical revolutionary with an enormous following.

|

| Musicians |

One of the orchestras in the Mendelssohn tradition was the Germania Orchestra which moved to Philadelphia but had trouble getting accepted, and disbanded. The members of the orchestra scattered and eventually reformed a Philadelphia Germania Orchestra, which largely took over the place and some of the members of the disbanded Musical Fund Orchestra, struggled for a few years, became part of Henry G. Thunder's Orchestra, which in turn was almost entirely taken over by Fritz Scheel's Philadelphia Orchestra. Even with this thoroughly local name, the Orchestra struggled for a few years, and would quite likely have dissolved into still other formulations, until the local Women's Committee took matters in hand. Leadership was provided by Fanny Wister, sister of Owen Wister the novelist, and granddaughter of Fanny Kemble. From that time on, particularly from the day of the hiring of Leopold Stokowski as a conductor, the Philadelphia Orchestra has pressed forward, and never looked back.

The Savoy and the Orpheus

Much of the music in Philadelphia is world-class, produced by eminent professionals who command high salaries for their work. As a result of many years of striving, through unions and otherwise, it is getting a little difficult to afford all this talent and excellence. That's one reason there is so much amateur musical effort, although it must be admitted that a city which appreciates music will almost surely generate a lot of amateur effort, just for the love of performing.

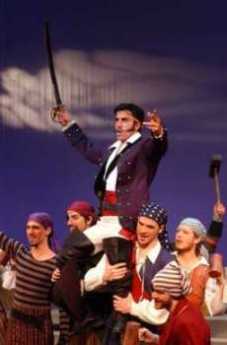

|

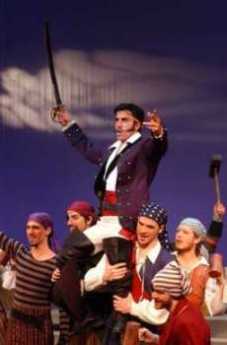

| The Pirates of Penzance |

The Savoy Company, putting on Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, and the Orpheus Club, which is an all-male choral society, were founded in Philadelphia around 1875. Both groups have little trouble attracting membership, although the members of the Savoy generally only perform for four or five seasons and then become inactive members. Members of the Orpheus commonly remain active members for fifty years, so it's harder for a newcomer to find a vacancy. Membership applications may possibly be enhanced at the Savoy by its reputation, deserved or undeserved, as a marriage market. At one time, fifty or more years ago, both organizations had a reputation for hard drinking, but during those days of Prohibition, many clubs served that function. Nowadays, alcohol is not a necessity with either of them.

|

| The Kimmel Center |

The exceedingly high hall-rental costs of the Kimmel Center and the Academy of Music are getting to be a problem for these amateur groups. The Savoy is lucky to be invited to have two performances a year at Longwood Gardens, and neither organization has to contend with paying professional musicians like its commercial competitors. Many performers in the Philadelphia Orchestra donate their time for the Savoy, among whom William Kincaid the famous flutist was one of the most enthusiastic. Without this help, it's unlikely the organizations would survive. Certainly, it would be hard to distribute four tickets per performance to members of the clubs, while striving to keep membership high.

All of this is just one facet of the general dilemma that it is increasingly impossible to break even in the performing arts, by ticket sales alone. Many taxpayers are Luke warm about music and see no reason why they should support it with taxes, and philanthropists can be fickle. It's a delicate balancing act because philanthropists are easily infuriated by strikes, and politicians are seldom attracted by what may be called the finer things. When the economy turns sour, ticket-buyers flee.

The Victor Talking Machine Company

Thomas Edison gets credit for inventing the phonograph around 1880, but what he invented was a concept of scratching a roll of tin foil with a needle. The approach wasn't really feasible, and Alexander Graham Bell modified it to scratching a wax cylinder. That was somewhat better, becoming the basis for the Dictaphone single-use system which persisted for several decades. But both Bell and Edison went on to more promising things. Meanwhile, a man named Charles Cros wrote an article in 1887, quite astutely describing the whole process we now know as the phonograph record.

Meanwhile, a young machinist from Dover, Delaware was puttering around with various steps in the sound recording process, and in 1900 was ready to find the Victor Talking Machine Company at 10th and Lombard Streets in Philadelphia. But while Eldridge Reeves Johnson had big trouble patenting Charles Cros's prior discovery, he was nevertheless destined to be gloriously successful with Victrola records in ways later Philadelphia inventors were destined to fail, utterly, with the computer. The Patent Office pointed out that while Cros had the theory right, he never even made a working model of his idea. His inaction had no right to be called "prior art", but was more aptly called an "abandoned experiment".

|

| Victor Company |

Johnson, on the other hand, worked out all the many practical difficulties in the road of developing a useful and salable product. The size, shape, and composition of the phonograph needles, the best speed of rotation of the platter, the motors to make it run uniformly, the best way to magnify the sound, the way to create a metal master, from which many cheap wax impressions could be made. And so on, fighting with competitors and patent claimants, just about every step of the way. With the great good fortune to make ten early recordings of Enrico Caruso for a trivial payment, the Victor Company was soon on its way and had to move its plant to Camden, where there was more room to spread out and grow. The Philadelphia Orchestra enjoyed huge financial royalties and climbed into the first rank in world orchestras, greatly facilitated by the near-by convenience of the Victor recording studios. Philadelphia became a music capitol where once it had been a Quaker city that didn't much approve of music.

As things happen in the technology industry, Victrola records were hit hard by the advent of radio, which also largely originated in Philadelphia. Inventories of unsold products suddenly piled up, and poor old Eldridge Johnson was reluctantly forced to sell out to RCA, the Radio Corporation of America. Johnson was paid $23 million to cash out of his business -- in March 1929. If he had waited another six months, his prosperity for a life's work would have been meager.

Reviving the Mummers

|

| Mummers |

There's a growing sense of alarm among loyalist Philadelphians that the Mummer's Parade may be in decline, possibly even in a fatal spiral of decline. Only 10,000 people participate in this folk ritual, while a few decades ago 25,000 people were participants of some sort. A great many people who don't participate, and don't attend, are having a lot to say about whose fault it is.

Much of the commentary is contradictory. The consensus among participants is that moving the parade from Broad to Market Streets, and then back again to Broad Street, somehow broke some vital strands of tradition. On the contrary, say some former viewers, the problem is that once you have seen the Mummers, you have seen them; there's no variety. If you take either argument seriously, you have to conclude that what seems appealing to the participants - continuity and stability - unfortunately turns off the spectators. If that's the situation it's hard to know how the parade ever got popular in the first place. So one or the other of these comments are wrong, maybe both are wrong. Unless both are right but insignificant, not the root of the issue.

Where everyone agrees is that the parade on New Year's Day is too doggone cold. Years ago the leaders tried to shift the parade to the Fourth of July, since in fact, it may have originally begun as an Independence Day celebration. What we now call "comics" were then called "shooters", because they carried and shot off guns. Since alcohol has always been an important attraction for these parades, it is easy to imagine the concern of the Quaker City about drunks lurching around the streets, firing real weapons. With the coming and going of Prohibition, sales of liquor on the street vanished, although there remains plenty of evidence it is still popular. On a political-social level somehow it is possible to sell beer at baseball games, whereas it is almost politically inconceivable to sell beer, or hot toddies, on Broad Street. No one could argue with a straight face that alcohol violates tradition.

As for that doggone cold, it isn't any colder today than it was when the Mummers parade was thronged, is it? Well, yes, it's a lot colder. Skyscrapers cast dark shadows at the end of short winter days. And tall buildings block the wind at their tops, with the wind then scooting down the side of the building to the sidewalk. That's the "Marilyn Monroe effect," and it's plenty real. So, it has to be noted that the parade migrated up from South Philadelphia to center city, at the same time center city became climatically inhospitable. To get a little technical, there's also the "sundown wind." As the shadow of nightfall moves from East to West, the warm air in the sunlit area rises up over the cold air in the darker region, creating a sundown wind. Add to this the early sunset of winter, throw the sundown wind against skyscrapers, and it's time to go home. To television.

It's my view that television, which I never watch, by the way, has a lot to answer for in the deterioration of the Mummers parade. If people who never watch the Mummers parade are allowed to criticize it, surely people who never watch television are also entitled to some surly comment. Back in the fifties and sixties, getting featured on television was a big thrill for the mummers. If the cameramen preferred performance in one place so they needn't move their equipment, their request was eagerly agreed to. There might even have been the prospect of big bucks since everyone knows show biz commands top dollar. Let 'em perform at City Hall, where the judges can keep warm on elevated benches, and politicians can accidentally walk in front of the cameras. But notice that all of the successors in the parade line are backed up from City Hall to Locust street, not performing for the sidewalks. And all of the performers, having strutted their stuff at City Hall will then disband, instead of continuing up to Vine Street, as they once did. It's no longer a parade, it's a performance at City Hall. For television, you might say, except that television has used up the material and is abandoning it.

For completeness, we should mention the bad luck of snow and rain for a few years in a row. And the discomfort with blackface, but the absence of black people. The absence of Jewish and Oriental brigades in an ethnic extravaganza deserves notice. You will occasionally see people at Philadelphia upper-crust dances showing off the Mummers Strut, but you aren't likely to see that on Chinese New Years. Whether newer ethnic groups were excluded from participation by the hard-core South Philadelphia Italian, Polish and Irish groups is not immediately obvious. In fact, it could well be the reverse, a sour-grapes rejection by the newer arrivals or their leaders. But all such sullen opinions are somehow unsatisfying, particularly when the parade retains such a noticeable tolerance for transvestite behavior.

My main suspect for the culprit of the parade's decline is television. It was sure a nice parade before that thing came along. The leaders of the mummers' parade must either find a way to cope with the monster or - fuhgeddaboutit.

Settlement Music School

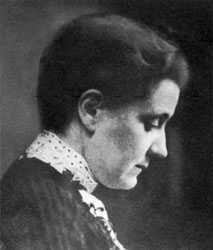

|

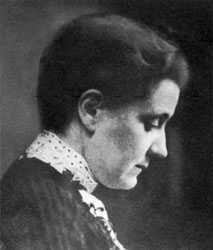

| Jane Adams |

The Settlement Music School has six branches, fifteen thousand current students, an $8 million budget, and three hundred thousand alumni. It tells you something about Philadelphia that an organization this large can exist for 98 years, and yet remain almost invisible. So let's tell a few things about it.

The settlement movement began in England around 1880, and was brought to America by a Quaker lady named Jane Addams. Her most famous settlement was called Hull House, in Chicago. Jane Addams seconded the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt at the Progressive Party convention, and was active in the formation of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, as well as the American Civil Liberties Union. She was a prominent suffragette, and as a Quaker, it might be expected that she was an outspoken pacifist. Remember, what we are talking about here is music.

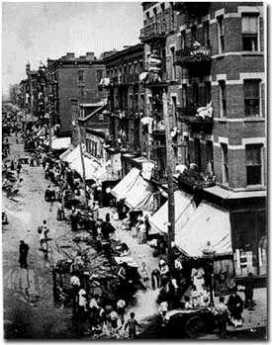

|

| tenement districts |

Settlements were what nice upper-class ladies called the tenement districts, and a settlement House was a center for activist women to go help the immigrant groups typically found there. Since there is obviously a lot of difference in what needs to be done to help recent ex-slaves, Italian and Jewish immigrants, and all the different ethnic clusters, the Settlement movement is an archipelago of very different forms of social work. One of the ways to appeal to different groups is through the teaching of music, and the teaching on expensive bulky instruments like pianos is quite naturally shared in a school building. While it is true that a couple of Settlement students are admitted to the musical big time at Curtis Institute every year, only a small proportion of Settlement students go on to musical careers. The three most famous musical alumni of the Philadelphia Settlement Music School were Chubby Checker, who invented a dance called the Twist, Albert Einstein. who played the violin in various chamber groups, and former Mayor Frank Rizzo, who learned to play the clarinet.

The mission of the Settlement School has gradually become the spreading of musical appreciation, especially among "the masses", and it measures its success in the size of its audiences rather than by occupying the center of the stage. This function is readily thrust off on them by the eagerness of public school boards to cut expenses, although the School is scarcely in a financial position to go all the way and assume the role of teaching music classes to 250 public schools. Nevertheless, when financial stringency forces the school board to cut expenses, their choice between a music teacher and a football coach is no choice at all. At that moment, a free-standing music appreciation school ceases to be a competitor and becomes a safety valve. When you hear the Settlement School is in need of money, you are likely being told about stringency in the public school budget.

Although the tuition is quite inexpensive for a music school, the students collectively contribute about half of the annual budget. The rest comes mostly from private charity. You really can't expect cutting edge innovation from school children or endowed charities. But somehow this school leaves you with an impression of big missed opportunity in the truly American forms of music like jazz and folk singing. Symphony orchestra was invented in Vienna and flourishes there, so it has a faintly foreign air to it. It's not completely surprising that both the sponsors and the subjects of Americanization for the Slums are hesitant to promote symphonic role models, while the sponsors at least are a little lost in the world of Rock. Not surprising, but something of a pity.

Astral

|

| Vera Wilson |

Brotherly love assumes all kinds of unexpected shapes in this city, and one of them is Astral. Vera Wilson recognized a critical gap in the Philadelphia classical music world, and in ten years has quite successfully filled it. Our town attracts the world's outstanding classical music talent to its schools, especially the Curtis Institute. It also supports the great established performers in its concert halls and recording studios. But how does a young virtuoso get from here to there, from a conservatory to the concert stage? Quite often, they don't make it at all, because no one helps them.

Pretty much single-handedly, and single-minded, ten years ago Mrs. Wilson established a non-profit organization to act as a bridge for young people with the talent and ambition to be classical musical soloists. What do such people need? Well, they need an incubator. They need membership in an organization that will provide them audiences, press notices, experience, a little emotional support, and some unobtrusive advice. And while Philadelphia is a world-renowned musical center, it could always use a few more concerts, a larger environment of musical enthusiasts, and a more enhanced reputation as the place to go if you plan to be a star.

Just about all these things are rapidly taking place. In ten years, Astral has put on nearly two hundred major concerts that would not have been put on, and every year puts on over two hundred local performances. Auditoriums that never thought of themselves as anything special are becoming the location of fine performances by performers who are clearly going somewhere. Musical affinity groups have formed around the idea of getting to know some virtuosos, helping some gangling kids, and even forming friendships with other local musical fans. Enthusiasm.

The formula involves a lot of hard work. Famous musicians have to be persuaded to contribute their time to auditioning prospective proteges. Concerts have to be planned, and auditoriums found to house them. Audiences have to be drummed up; pamphlets, advertising, and publicity have to be created. And paid for. Foundations have to be approached, grant applications have to be written, private donations solicited. Somewhere, $600,000 a year has to be raised to promote 26 rising stars. The whole thing would cost ten million a year if it were commercial.

Mrs. Wilson, who is not herself a musician, likes to describe herself as a groupie. It is a little hard to reconcile this elegant cultivated Argentine expatriated with the groupie concept. But maybe not. Perhaps we all have some enthusiastic groupie-ness talent in us.

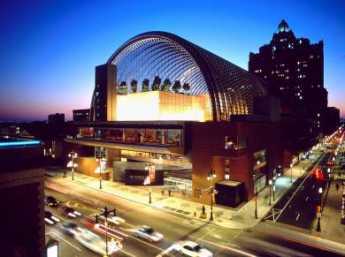

The Kimmel Center: Comments On The Economics of Music

|

| Kimmel Center |

In 2001, The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts opened to the public, at a cost somewhat to the North of $200 million, and an annual budget in excess of $80 million. Although the generosity of Sidney Kimmel and Raymond Perelman must be gratefully acknowledged, and the ambitious energy of Philadelphia's political and musical worlds must be admired, there is little question that the city strained its resources to the utmost to achieve the new center. The Philadelphia Orchestra must appear on anyone's list of the best symphony orchestras in the world. It's likely going to stay there, too, because the orchestra stands on a wide base of associated Musical schools, chamber music groups, and intensely loyal musical audiences. As they say in baseball, they have a deep bench.

Nevertheless, software piracy has just about eliminated an important source of income from the sale of recordings, seat prices are dauntingly high, other symphonies and other forms of entertainment have greatly improved in recent years. First-class musicians are not paid like sports stars, perhaps, but the top layer begin their careers with salaries in six figures, and top conductors commonly receive a million dollars a year, just like corporate executives. Between the high costs and the practical upper limit to what audiences will pay for a seat, about a third of the budget must be subsidized by some form of donation or fund-raising. It takes a lot of effort to raise thirty million a year.

For reasons not entirely clear, the Kimmel center

|

| Academy of Music |

is a free-standing corporate entity, whose main tenant (the Orchestra) owns a competitive music hall, the old Academy of Music. In other words, the capacity of Philadelphia's musical locations has been substantially increased. Increased, that is, beyond the metropolitan area's capacity to fill seats for classical music. A season's list of seventy-five productions may not fill the capacity, but the production schedule is limited by the fact that almost every production sustains a loss which must be made up by fund-raising.

Following Julius Caesar's

|

| Julius Caesar's |

motto that Fortune Favors the Brave, the leadership of the town has embarked on a daring musical exploit. The remarkable design team constructed the hall along highly innovative lines, based on movable wooden wall panels, controlled by computers. The hall itself becomes an instrument, slowly adapting and learning from each orchestral piece to produce an evolving product that no orchestra could produce without the hall to surround it. No one yet knows how far this idea can be taken, but it is possible to imagine four or five quite different versions of the same piece, each one recognizably distinct and with its own following.

And revolving stages, adaptable hall design, and computerized modeling make it possible to have performing arts, not merely classical symphonies. It remains to be seen whether the designers can achieve perfection in a number of different forms, not merely limiting the design to a specialized version for a single purpose. If that works, capacity can be increased by redefining capacity. Just imagine what a wedding you could hold there.

And just imagine how that worries the owners of the other six theaters in the neighborhood. In fact, just imagine how it worries the Philadelphia Orchestra to learn that there are plans to bring other visiting orchestras to town. Or how it worries other cities to hear that Philadelphia hopes to draw musical audiences from a long distance. There's going to be some creative destruction here, and some high adventure.

Armonica, Momentarily Mesmerizing

|

| Ben Franklin's Glass Armonica |

Everyone knows Ben Franklin spent a lot of time holding a wine glass. Evidently, he noticed a musical note emerges if you run your finger around the open mouth of the drinking glass, and systematically studied how the tone can be varied by varying the level of liquid in the glass. The same variation in emitted tone relates to variations in the thickness of the glass. So, he set up a series of different sized glasses impaled on a horizontal broomstick, enough to cover three octaves, rotated the broomstick with a treadle like those used for spinning wheels -- and made music. The tone has a haunting penetration to it, which induced both Beethoven and Mozart to write special compositions for the harmonica, and the Eighteenth Century went wild with enthusiasm.

|

| Glass Armonica |

Unfortunately, a number of the young ladies who played the armonica went mad. We now recognize that since the finest crystal glass was used, with very high lead content, the mad ladies were suffering from lead poisoning after repeatedly wetting their fingers on their tongues. As a matter of fact, port wine at that time was stored in lead-lined casks, resulting in the same unfortunate consequences, which included stirring up attacks of gout. Franklin himself was a famous sufferer from gout, which was more likely related to the port wine than playing the harmonica, in his particular case.

Anyway, the reputation for inducing madness added to the spooky sort of sound the instrument made, attracting the attention of a montebank named Franz Anton Mesmer, who falsely claimed to be the father of hypnotism. Mesmer enhanced the society of his stage performances by hypnotizing subjects while an assistant played the harmonica, meanwhile relating all sorts of wild tales about animal magnetism. This was pretty sensational at the time until a young man in an audience suddenly died. It is now speculated that the victim probably had an epileptic seizure, but the news of this public fatal event pretty well finished Mesmer as an evangelist and the harmonica as a musical instrument.

|

| Franklin Court |

There's a replica of an armonica on display in the Franklin Court Museum around 3rd and Chestnut, which we are vigorously assured is not made with leaded crystal glass. The Park Rangers put on two daily performances by request, at noon, and 2:30 PM.

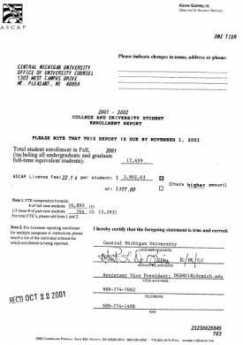

ASCAP Methods

Composers and performing artists are both musicians but belong to different unions, different styles of life, and different payment systems. Composers typically sell their work to publishers of sheet music, to orchestras, to producers of plays and movies, or anyone else who commissions them to write music. About 1914, they decided that wasn't fair, because it pays the same for flops and successes. Somehow, the successful composition should bring greater reward than one that fails. So, ASCAP, the Association of Composers and Publishers was formed, to collect royalties for the composers when their pieces are played. After ninety years of adjusting, their system has become fiendishly clever.

|

|

A copy of an ASCAP form used at an American university. |

Some 68,000 composers have joined the organization, and ASCAP sells annual licenses to broadcasters and producers, allowing them to perform anything registered by one of the members. ASCAP makes an approximation of what the broadcaster is likely to play in a year, and bases its license fee on that. Then, it studies the program logs and other material, and figures out how much of the fee should be credited to which composer. In a system covering millions of performances a month, there must be some inaccuracy, but there seems to be relatively little dissatisfaction among the composers, and the broadcasters are more concerned with the size of the license than the fairness of its redistribution. Since this system is obviously much more efficient than collecting fees performance by performance, the people involved and the courts which oversee the process seem to be willing to overlook minor imperfections. Even the monopoly antitrust feature was softened by the appearance of a second agency, BMI, in 1940; which now has over a third of the business.

Such a system has to be audited, to keep down the grumbling and keep away the plaintiff's lawyers. So, the fairness of the formula is tested by sampling techniques, with computers and all that. In fact, there is quite a large business of consultants who audit for a fee. Out in Darby, Pennsylvania, there is a place where teams of middle-aged ladies sit in a big open hall and watch television being piped in from all over the nation, keeping score on notepads, and turning it over to computer operators for processing. The coffee consumption in that room is simply astounding, and so they need a ten-minute break every hour, but it's considered to be a good job.

When you do a little rough maths, questions do get raised about this. Between them, ASCAP and BMI seem to assess annual fees of about $700 million and turn 80% of it back to composer members. That means that retained expenses are about $140 million. That's a trifle hard to account for, and rather strongly suggests that lobbying activities must be appreciable. The system is clever and efficient, it passes its audit checks. But the question nevertheless remains: is it legitimate? Since any question of legitimacy is ultimately determined by Congress, campaign contributions are always a wise precaution.

ASCAP keeps expanding its reach. It recently started to demand that Girl Scout camps pay for a license for their campfire singing. Before that, the last big uproar was over music played in elevators. And then, there is the perennial anecdote about Happy Birthday. Two schoolteachers in Kentucky are still being paid about $2 million a year as royalties for the playing of that song in restaurants and radio programs, and the copyright still has a couple of decades to go. It's the duration of that copyright that is the most dubious part of this business, and the one which will need the most lobbying money to justify.

The Man Behind the Mann

|

| William Leonard |

William Leonard, a distinguished lawyer retired from the distinguished firm of Schnader, Harrison Segal and Lewis addressed the Right Angle Club recently about his adventures running the new and improved Mann Center in Fairmount Park. A member of the board, he was suddenly asked to act as interim CEO when Peter Lane went on to another career. His task was to hold the organization together, while a permanent replacement was recruited. It turned out that directing an organization and actually running it are two entirely different things. It was necessary to learn about show business programming, the problems of rock groups, the whims of donors, the headaches associated with food vendors, and lease renewals with city governments, not to mention the rigidities of state and federal rules. Leonard obviously enjoyed the challenge, although most of us wouldn't.

The Philadelphia Orchestra had been playing summer concerts in the park since 1930, eventually adopting the name of Robin Hood Dell, East. Although the city contributed a couple hundred thousand dollars of support, and several hundred thousand other dollars came from non-ticket sales, classical music was always a long way from breaking even. The big revenue came from Rock Concerts, which may have been humiliating for the classical musicians of international fame, but was nevertheless what it took to survive, take it or leave it. Fred Mann in 1976 took the lead in raising funds for a roofed outdoor performance center, and the enormous energy of Peter Lane was brought from the New York Pops to get things going. In ten years, the Mann Center increased its outside support to $2.8 million of the $8 million annual budget and was putting on forty performances a season, with attendance increasing by 20% from 2006 to 2007. All this was accomplished in spite of the city government dropping its contribution to zero, and dropping music courses in the school system.

In a sense, the city stringencies may have been a blessing for the Mann. A second capital campaign raised $15 million for expanded facilities and parking, as well as an education center, to meet the new community need. A complimentary ticket program distributes 50,000 free tickets yearly, and seats on the lawn cost $10. If you want to get under the roof, it costs more. The free program familiarized parents with the program, and the educational center is now thriving.

Mr. Leonard brought along the new CEO, Cathy Cahill, and it looks as though he made a good choice. She's only been here for 19 days, but she went to Temple and Drexel before taking jobs out of town. She's a cellist herself, which should ease labor relations somewhat, although the pep and enthusiasm are surely innate. We hear that SEPTA is planning to re-open the R-5 station, and jitney bus service for the whole Park complex will be shared with the Please Touch Museum and other new activities in the 1876 exhibition area. There are plans for a Shakespeare repertory group to have a home here. This drive and enthusiasm are going to be necessary because Rock Groups are now competing in the Wachovia Center, and the Tweeter Center in Camden. Apparently, the secret of classical music finances leaked out.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1479.htm

WRTI, Classical Music and Jazz

|

| Susan Lewis |

Susan Lewis recently entertained the Right Angle Club with a description of her life as the scriptwriter for WRTI, the local classical music station. WRTI could be described as one of three local affiliates of National Public Radio, the network content provider headquartered in Washington DC. The other two are WHYY, a talk station, and WXPN, the University of Pennsylvania station devoted to folk, rock, blues and root music. Another way of describing WRTI is that it took over the role formerly served by WFLN before it was sold, incorporating it into Temple University's jazz station. It plays classical music from 6AM to 6PM, and then plays jazz in the evening. Philadelphia thus really only has half a classical music station, when most cities who are home to a major orchestra have at least two. It is not clear whether this anomaly is a comment on the local radio climate or the future of its musical one.

|

| Philadelphia Opera House |

The question came up as to just what is classical music since there are turf boundaries for the affiliates of National Public Radio. Susan Lewis, who has the surprising background of being a former corporate lawyer has apparently given this some thought. She offers the opinion that classical music overwhelmingly consists of music with multiple performers. Orchestras, opera, chorales, and chamber music characterize the topic more than pre-contemporary origins. A brand new symphony would naturally fall into the classical music category, while songs by Frank Sinatra would not, even though excited announcers might call his songs classics. Following this theme, classical music seems to fit with jazz, which consists of several soloists working on variants of a common theme. The sad question thus comes up whether Philadelphia's declining interest in classical music might in some way reflect social fragmentation within a metropolitan community which historically has highly valued cooperation and consensus. One hopes that's not the case.

|

| WRTI RADIO |

Playing a succession of recorded musical selections sounds as though it would be a low-budget operation, but WRTI costs $3.6 million to run, annually. The scriptwriter gets up early, reads the day's artistic news and events, and some auto traffic reports, and records one-minute vocal interludes between the pieces of music. About once a week, a special seven-minute segment is assembled from excerpts from interviews or interludes relating to a theme in the artistic world. One taped recording of carillon music and commentary proved to be quite charming and entertaining, including the news that the carillon in Holy Trinity Church is the oldest in America. Since a bell is a variant of a tuning fork, the bells of a carillon chime with a very long period of decay, creating a problem for both composer and performer to avoid successive notes which conflict unless there is a long pause. These magazine-like pieces of hers are always organized around a main emotional "hook" of some sort, and Susan finds they are very time-consuming to assemble. That leads to a constant succession of inflexible deadlines, just like lawyers' briefs before a legal deadline, generating an excitement strangely exhilarating to the participant, and highly mystifying to outsiders.

As the central focus for dozens of emails and text messages about the goings-on of the local artistic world, the job of town gossip for the art world is an ego trip only suitable for a person who revels, with affection, in the endless wealth of art and anecdote in Philadelphia. As bloggers also know, this job constantly surfaces interesting news tidbits that surprise and please many people. Like the fact that William Penn's hat on top of City Hall is filled with graffiti. Or that a secret colony of Lenni Lenape Indians still exists in town. Or that the forthcoming HP radio standard produces outstandingly high quality.

Ms. Lewis is an asset to our town.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1521.htm

Quaker Carillon

|

| Carillon Bells |

A carillon is a graded series of bells in a belfry, to play tunes. Quakers avoid bells and belfreys, but instinctively grasp the concept of a carillon. Why is that so?

Spoken messages at an unprogrammed meeting, like ringtones of a carillon, are followed by persisting vibrations of varying intensity. Care must be taken, no matter how pure the next message may be, to preserve harmony with the ring decay of the tone it has just followed. Not too soon, not too unrelated.

Overly long delays between messages may be discordant, breaking up the tune unless the message is harmonious. Lacking a tune, the messages fall apart. A silence of even longer length may restore the tune for a gathered meeting, or the next speaker may gently rebuke the interrupter. Sometimes the difference is distinguishable only when you know the personalities. A meeting without a tune is a disappointment, pointing toward individual experience instead of group unity. But death or other catastrophes can have its message destroyed by trite commentary. Rising above triteness can be one way a "weighty" meeting rises above its rank to demonstrate the fearlessness of leadership; failing to rise to an occasion is a way of demonstrating ordinariness.

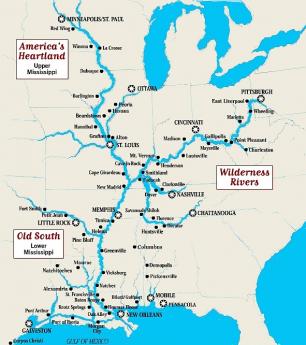

Mississippi Carillons

|

| Mississippi River |

The Mississippi River runs over a fifty-foot ledge in the city of Minneapolis, its waterfalls providing power to mill flour, but definitively ending northward navigation on the river. In the eddies and side streams around the rapids, great swarms of Canada geese paddle about, quacking, right in the center of the city. A church with a carillon of shiny bells stands on the bank above this scene, its many bells ringing at once in clashing sounds quite evocative of the gaggles of geese on the river below. Likely, the effect is intentional, although at first encounter it strikes many as dissonance. Acknowledged to be artistic, it is still not music. But others think it is.

At the far opposite end of the Mississippi, in New Orleans, jazz was born. A group of musicians plays together in an aimless way, until one soloist strikes up a melody, with variations. In time, another musician and then still another, take up the melody, playing different variations on different instruments. Sometimes the whole group joins together in a minor patch of a symphony. In time, one musician wanders off on another theme, or the whole group seems to agree on when to stop.

There's a small Quaker meeting in Minneapolis, but most of the Quakerdom branches off to the west of St. Louis up the Missouri River, or to the east of St. Louis up Ohio. There's less overt religious music in the Quaker meetings up Ohio, but there is some. Either way, there is usually a sense of timing and harmony in the verbal messages. Some congregations are like a Belgian carillon, interweaving themes as exquisitely as Bach's Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring. Others interact directly like a game of volleyball. Only a few seem to find pleasure in independent vocal ruminations resembling a jazz performance, and those are usually meetings too small to organize a carillon effect. Three hundred years ago, it was an important question for Quakers whether to worship together in a group. No minister, no ceremony, no sacred music; just sitting silently together in a gathered meeting. Naturally, the question arises, if you intend to sit quietly in a chair, why not do it at home, alone. Robert Barclay seems to have settled the issue; the purpose of a gathered meeting is to discover and maintain consensus. Robert Barclay had no thought of composing jazz music, and often it does not emerge. But sometimes, and in some places, that's what it resembles.

Frederick Mason Jones,Jr. 1919-2009

|

| Mason Jones |

Classical music, however else it may be defined, strongly implies music played by an orchestra, or at least a group of musicians. It thus should be no surprise that the members of a famous orchestra bond together for most of their lifetimes in a sense far beyond the ordinary meaning of teamwork. If you are good, really, really good, you will come to the orchestra as a boy, devote every hour of every day to the orchestra, and step down only as a famous old man when you sense that reaction times have slowed. You sit together, travel together, rehearse together, and talk a language of detail which no one else can fully comprehend. Mistakes that one of you made forty years ago in performance, are still joked about because your colleagues know you still feel the pain of it, just as they share their own infrequent but no less fully remembered, moments of failure, largely unnoticed by the audience. When one of your colleagues dies, you turn out by the hundreds for the funeral. And when the hymns are sung, the organist is ignored, struggling to keep up with the people who really know music.

Mason Jones attended the Curtis Institute, itself a collection of prodigies, and was hired by Ormandy after a single audition; a year later he took the position of a first horn and kept it until he finally sensed he was passing his prime and laid it down. He was featured in the many recordings which defined the orchestra, and the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet. He sometimes recorded as a soloist, but he thought of himself as an orchestral horn player, teaching orchestral horn at the Curtis to many generations of aspirants. He even conducted a little, usually in small groups. His comment on that was that it doesn't take much to be a conductor. "Just ask any orchestra player." At his funeral, it was related that the second horn once had two solo passages repeated within a larger piece, but when its time came there was silence. The second time around, it was played faultlessly. Afterward, Mason was asked what happened. "Fell asleep," he answered. And the second time? "I just played it for him."

|

| St. Peter's in the Great Valley |

Mason's funeral was held at St. Peter's in the Great Valley, illustrating that strange combination of artistic prodigies with modest beginnings, and the highest of high society, who mix together to create a great orchestra. A very well-groomed lady was heard to remark that this was where she had her coming-out party. St. Peters was founded as an Anglican mission church in 1700 in the Welsh Barony, built a log cabin church in 1728, replaced it with a little white jewel of a church in 1856, and added new buildings in the past few years to accommodate the population growth in the valley. The church has abundant well-tended land, sited on a hilltop surrounded by high hills, quite suitable for a college or private school campus. The homes in the area are a step beyond splendid, hidden in the wooded countryside. Unless you know precisely where to go, the tangle of country roads will defeat you. But the arterial of U.S. 202 is only a few miles away, and Philadelphia's silicon valley nestles beside the highway, inevitably closing in on the countryside. There will be horses and kennels and fox hunts in the region for another decade perhaps, but the new world is moving in on the old one, from all directions.

Curtis Center

|

| The Curtis Center |

Tell your taxi driver that the Curtis Center is between 16th and 18th Streets on Locust, and not at 6th and Walnut. The big building next to Independence Hall is the former site of the Curtis Publishing Company, where all the money was made with the Saturday Evening Post. The Curtis Center is the present home of the Curtis Institute of Music, founded in 1924 by Mary Louise Curtis Bok with the advice of Leonard Stokowski, and with the determination to make it the best school of music in the world. The big competition, then as now, was the Juilliard School in New York, which is considerably larger. The New York competitor has the advantage that it sits on top of the Metropolitan Opera House within Lincoln Center. The Curtis, however, has a trump card; no student pays tuition, and the school tries to provide assistance for other costs of the students. Because of Juilliard's location closer to many performing arts centers, it can draw on a larger pool of commuting students and faculty, and is probably considered the top choice by the talented pool of applicants. But Curtis is gaining; only two of the accepted applicants from last year's class of 48 students chose to go to another school.

|

| Colburn School of Music |

In this fiercely competitive game, the school which is coming from the rearmost recently is the Colburn School of Music at UCLA. Not only does Colburn have Mr. Colburn's declaration in his will that he wanted to make it the "Curtis of the West", it is also heavily supported by Universal Studios, and has the additional advantage that Oriental students are flocking to the United States for musical training, and there are, of course, a lot of them. The previous director of Curtis is invited to China every year at the expense of the Chinese government, just to listen to what Chinese students sound like. It's sort of like inviting the college admission officer to your home to listen to your children describe their extra-curricular talents, but that's the way things are in the highly, highly competitive world of music. Running schools of music are no exception to that; don't forget music schools named for Peabody and George Eastman, and Boston's New England Conservatory of Music. Definitely a hobby for a person of means.

|

| Gerry Lendfest |

Like Gerry Lendfest, the Chairman of the Curtis Board. On his own, he bought the old Locust Club property and the two neighboring houses, and gave it to the Curtis if they would pledge to raise $35 million to fit it out. That's been done, and there is now a big hole in the ground across Locust Street from the Wannamaker Chapel of St. Mark's Church. The plan is to construct a five-story building on Locust Street in conformity to the wishes of the Planning Commission, but the building will rise to the level of a 9-story building on Latimer Street. Somewhere tucked in there will be an orchestra rehearsal center, a library, and many instrumental practice halls. Plus a dining room for everybody in the school, and about 85 dormitory rooms for students. Mr. Lendfest is obviously a keen competitor in the music school game.

The school has 85 faculty members for 165 students, half of whom come from overseas, and are male/female 50%. An occasional student is seven years old, in the style of Mozart, and every single student knows that just about every other student is just about as talented as he/she is. The test of it all is the careers of the students, who quite naturally fill up many of the places in the Philadelphia Orchestra. Famous graduates are Leonard Bernstein, Samuel Barker, Juan Carlo Menotti, Ephraim Zimbalist, and many others. There's little doubt that the original idea was to bring Central European music to America, but two world wars and the relentless pressures of outstandingly talented students have broadened the horizons to a modern vision of the future of music. One particularly significant development is the laying of fiber-optic cable from Temple to the Kimmel Center, and a planned branching to the Curtis Center. That's the new and improved Internet II, which will make virtual conducting of virtual orchestras all over the world a possibility. Keep tuned.

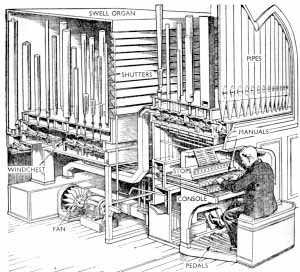

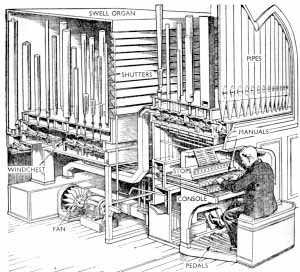

Pipe Organs, and Similar

The Franklin Inn Club was pleased to hear a talk about pipe organs the other evening, by one of its members, Wesley Parrott. Wesley has degrees in the subject from the Curtis Institute and Eastman and was accompanied by Riyehee Hong, who has a Ph.D. degree on the subject from the Moore College. Wesley is now the organist at St. Mary's Church on Cathedral Avenue.

|

| l'Orge de Valere |

The flute is just about the oldest musical instrument if you regard a pipe organ to be essentially a large collection of flutes with a single mechanical air blower, controlled by a console. Bagpipes almost fit that description, too, except a bagpiper first fills the bag with air he blows in by himself, and fingers the holes in the pipes for individual notes, whereas the pipe organist has mechanical assistance to supply the air and control the pipes.

It seems to have been Emperor Charlemagne who decreed the pipe organ would contribute the main music of churches, and to fit this role, pipe organs in France and Italy evolved in the direction of elaborating the overtones and color characteristics of the organ as sort of a soloist in a church. Organs from this distant era are still playable but seem tiny in comparison with later examples. German music, in general, has always emphasized melody over elaborate overtones, and German organs evolved in the direction of distinctive notes in counterpoint. That has been true for centuries, but it was the missionary surgeon Albert Schweitzer who most recently made great steps away from French influences back toward melody and counterpoint, both in musical composition and in mechanical modifications of the instrument to suit that baroque goal. The mechanical underpinning of this distinction lies in the immediacy of response and shortening of tone decay, making the notes crisper. The older French version tends to smear the notes together, like a young person who talks too fast. The whole French language shares that characteristic of slurring words together, and speakers thus seem to be talking a little too fast to be understood. The German language is more staccato, with distinct separate words. In general, pipe organs tend to be either of the French or the German style, but there is a great deal of individual variation, resulting in subtle distinctions lost on most audiences. The design and construction of organs remained essentially unchanged from 1390 when l' Orge de Valere" was published by Guy Bovet, until 1876, when the great modern innovation of the electric organ was displayed in Philadelphia.

|

| Pipe Organ Sketch |

In fact, two modern changes were heavily American-influenced. The most important change in the mechanics after five hundred years was introduced at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, by Hilborne L. Roosevelt, a cousin of Teddy, and son of S. Weir Roosevelt. The organ on display was the main organ of the main exposition building and created a sensation. Although he was only 37 years old when he died ten years later, Roosevelt became one of the largest organ manufacturers in America, a friend of Thomas Edison, and was recognized for a number of electrical inventions. Electrical control of the blower and valves greatly expanded the potential for size and complexity of the keyboard console. Up until that time, the keys were pounded with the organist's fists, and organists therefore somewhat resembled blacksmiths, both in musculature and temperament. The application of electricity greatly expanded the complexity and artistic potential of both the German and French styles. Meanwhile, the symphony orchestra was evolving throughout the 19th Century, and now the organ was able to imitate the whole orchestra. This evolution soon developed a mass market in the huge silent movie theaters of the early 20th Century, which in turn generated a pressure to evolve orchestra-like characteristics in the organs installed in the theaters, adding extra pipes and tones to suit that taste, which was exuberant. The advent of sound movies would soon eliminate the need for pipe organs in movie houses, but the instruments were durable and built into the walls. A few of them therefore still remain, largely unused, and probably unusable. The Philadelphia region is unusually rich in pipe organs of various sizes and complexity; students of the subject come here to tour them.

Philadelphia's Kimmel Center has a new pipe organ, with two consoles to suit the two main styles of organ music, solo of the Charlemagne sort, and orchestral music. Wesley feels too much emphasis was placed on maximizing the seating capacity of the Kimmel auditorium, causing the organ to be fitted into a narrow tunnel-like enclosure. The resulting sound of the organ has a uni-directional quality which is unrelated to the organ itself; some people criticize the overall result as "assaulting" the audience, but whether for better or worse the Kimmel Center distinctively has a Kimmel sound.

The electronic organ, as distinguished from the electric organ, doesn't use pipes, it synthesizes sound. It is far cheaper to manufacture, but is undergoing such rapid change in so many directions nowadays that it resembles the home computer; you have to go to the expense of getting a new one every few years. The electronic organ is clearly catching up with the range and quality of pipe organs but has not yet reached parity except in specialized situations. But its rapid and relatively inexpensive adaptability gives it a great advantage when musical tastes are changing. Modern music places much more emphasis on percussion, and modern society is much less attracted to great big hollow churches. Electronic organs thus change direction faster than multimillion dollar organs of the traditional sort, and slowly, slowly, the quality is catching up, too.

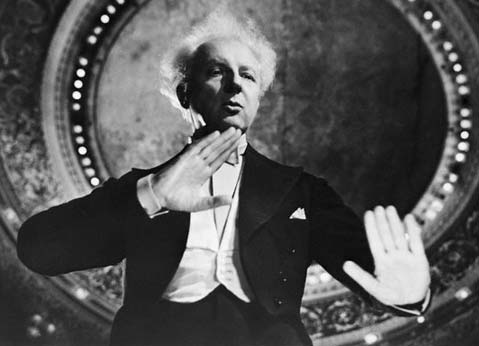

L. Stokowsi and the Philadelphia Orchestra

|

| Leopold Stokowski |

Leopold Stokowski remains unchallenged as the greatest musical leader in Philadelphia's history. Serious musicians acknowledge his eminence in musicianship, while it must be admitted he enhanced his reputation with a great deal of showmanship. Showmanship makes Philadelphia grit its teeth.

Stokowski lived to be 95, so it is easy to forget the Philadelphia Orchestra was pretty insignificant when he arrived in 1912. Together with a great deal of money available from the Curtis family, he pretty much had a free hand in upgrading the players, one by one, making radical changes in the ingredients of his unique "Philadelphia Sound" by changing the proportionality of various instruments, modifying the physical variants of each instrument, rearranging the seating arrangements of the players on the stage, and responding to the acoustical properties of the Academy of Music. He composed hundreds of personal recordings of classical pieces and introduced dozens of new modern composers and soloists. He was a musician's musician, and partly because of his very long life he was able to change the nature of American classical music, putting Philadelphia at the very top of the heap.

|

| Mary Louise Bok |

He was also very quick to make use of new technology and new instrument variants. It was perhaps a bit of luck that RCA Victor was located just across the river in Camden, so the revenue from recordings was very substantial, right from the early years of this new form of entertainment. He appeared on radio and later on television. His movie Fantasia was the greatest and perhaps an only movie to make a smashing success of classical music. Behind the scenes, he took great care with arranging the instruments for recording sessions. Much of the vaunted acoustics of the Academy of Music was simply peculiarities of it, against which he made the musicians adapt their effort to create a characteristic sound which was partly due to the hall, and partly a conscious response to it. When the Orchestra took its many trips to other cities and nations, great care was taken to adjust the volume of component sounds to the size of the hall, emphasizing various instruments to exploit local peculiarities.

|

| Gloria Vanderbilt |

And finally, the exasperating part. He discarded the baton, directing with his bare hands. He discarded the score and directed from memory. He arranged the lights to shine only on his head and hands. He had temper tantrums with questionable justification. His first wife was named Lucie Hickenlooper but she changed it to Olga Samaroff to seem more exotic and urged Leopold to affect a continental accent and emphasize his middle European ancestry, even though he had been born and educated in England. He had a famous affair with Greta Garbo; it probably did not need to be famous. He married two heiresses with great fanfare and notoriety. They said he was gorgeous. Just how much of all this was due to his innate egotism, and how much was the affectation of an impresario is left to one's imagination. It is not difficult to imagine friction between him and the members of his board of directors.

|

| Greta Garbo |

As time has gone on, the physical acoustics of the Academy of Music has changed. Carpets have been added, seat backs replaced. When a new pipe organ was added, its weight required a second layer of flooring to hold it. Somehow, Stokowski's successors have been unable to change the orchestra to compensate completely for these subtle modifications; perhaps they had a different emphasis. One wonders if the veneration of former successes of many sorts might have held back the leadership of the orchestra from being sufficiently radical. In Stokey's day, radical changes were the expected thing, today they are viewed with caution. And most of all, there has been a role reversal between conductor and players. In the beginning, the players were on trial with the conductor. Today, the players are far superior in quality because of fame and the Curtis Institute; except for personality and showmanship, most of them could qualify as soloists. Consequently, any new conductor is on trial with the players, and the players' glory in it a little. In a profession filled with neurotic insecurities, there isn't room for quite so many egotists. Everybody seems on the edge of asking whether they need the orchestra, or the orchestra needs them; at times of financial downturn, that extends to the board of directors as well, and even to the audience.

The Philadelphia Orchestra is far stronger than it used to be. It trails a century of triumphs, a pantheon of stars, and the remarkable strength of the Curtis Institute continually renewing its talent. But like so many institutions with a glorious history, it must be careful not to rest too confidently on its strengths.

Willow Grove Park

|

| Richard Karschner |

The Right Angle Club was recently highly entertained by a talk by Richard Karschner about the hay day of Willow Grove Park. Mr. Karschner appeared before the club in full uniform of the Marine Marching Band with medals and quickly demonstrated an immersion in this topic that must have taken a lifetime to perfect. He put on a virtuoso performance, a prepared speech perfectly timed to an automated slideshow, which was in turn in perfect synchrony with an automated musical background, exactly tailored to fit the momentary subjects. He concluded with a brilliant brief solo on the cornet (trumpet), using double and triple tongue-ing. To some of us who remember some futile struggling with the trumpet in our high school marching bands, the skill demonstrated was certainly impressive.

|

| Music Pavilion |

To go back a moment in time, the trolley car was the main method of public transportation in the last half of the 19th Century, blanketing the cities of America and their suburbs, and connecting to the trolley lines of other cities through an interurban network. Somewhere the idea developed of building Amusement Parks out at the far end of suburbs, to attract riders into using the trolleys for more than just commuting; there may have been as many as seventy or eighty such permanent circus grounds in America at one time, with more elaborate attractions that could be managed by traveling circuses. Philadelphia had several such trolley parks, notably Woodside Park in Fairmount Park, serviced by the "Park Trolley". But in 1896 Willow Grove was created on the edge of Abington, far more elaborate than any others, at the intersection of Old York Road and Easton Pike (Rte 611). Its terminal could hold as many as a hundred trolleys at once; the ride from Center City Philadelphia took 70 minutes and cost 15 cents. The area had mineral springs and had long been a favored vacation spot. Horace Trumbauer designed four or five of the buildings, and the Park eventually included a lake with rental boat rides, an arboretum, amusement rides, restaurants, a fun house, silent movie theaters, rodeos, roller coasters, a picnic park, and even an artificial mountain with a slow scenic ride up but a rip-roaring fast descent. By far the most central feature of Willow Grove was the 4000-seat music center, dominated by John Philip Sousa and his band giving four performances a day. Other musical performers were Victor Herbert, Walter Damrosch, Arthur Pryor ("The Whistler and His Dog"). Many of the ideas of Willow Grove are now to be found in the modernized form at Disneyland, but for twenty-five years music under the direction of John Philip Sousa was really the central unifying feature.

|

| John Philip Sousa |

It's generally held the arrival of radio broadcasting caused the decline of Willow Grove, although "The March King's" immense energy declined toward the end, as he began to enjoy being a multimillionaire. The composition of marches was in fact only a minor part of his musical output, which included among other things 16 full-length Broadway musicals. He was a national champion trap-shooter and a horseman of some note. One arm became nearly useless to him after a fall from his horse. Meyer Davis took over in the last few years, but a major fire pretty well finished the place off just in time to be buffeted by the 1929 crash. There was an attempted resurgence in 1933, but circumstances which made Willow Grove a successful "Virtuoso Solo" just couldn't withstand the competition of the automobile and television, and the land was finally broken up and sold for $3 million in 1976. Remnants of the gilded past are now scattered around the Willow Grove Shopping Mall, for those who wish to renew fond memories from their childhood. Or perhaps their grandparent's childhood.

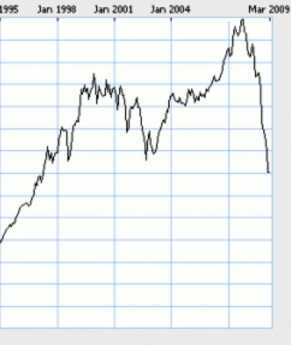

Perpetuities

Although some churches and mummies are well preserved after thousands of years, and no doubt a few corporations do last century, the fact is most of them don't last very long. Most new corporations go bankrupt within ten years, and only one (General Electric) of the original thirty members of the Dow-Jones Industrial Average existed in 1900. Members of the Dow may seem the biggest and best, but in fact, live on a slippery slope. Not-for-profits, like churches, may do somewhat better, although the handful who approach perpetual status may be rare exceptions. One big reason not to leave a major bequest to any of them may well be that most will not survive. While we are on this subject, the same reasoning applies to the stock in for-profit corporations. Since few of them thrive for more than seventy-five years, the idea of buying their stock, holding it forgotten in a safety-deposit box, and passing it on intact to heirs, is probably doomed to investment failure. The oldest stockholder company in America is called the Proprietors of West Jersey, founded in 1676 but still meeting once or twice a year. It would be moderately interesting to know how well this investment performed over the years, but Google sounds like a better bet offhand. Just don't hold it too long.

|

| Cotton Mather |

There may be a connection between success as a non-profit and success in the merciless marketplace. Those who have compiled statistics will tell you that steadily withdrawing more than 4% a year from an endowment portfolio, sooner or later leads to a day when there is nothing left. Most trustees expect better results than that, and most managers of non-profits will need more than that, no matter how big the pile was when they started. Sooner or later, markets will decline, mistakes will be made, and the endowment will be exhausted by "emergency" withdrawals which relentlessly withdraw more than 4%. This pitiful decline might be avoided by gathering the managers of influential non-profits together, giving them a stern lecture, and somehow forcing them to live within their means, but offhand nothing sounds more futile. Jonathan Edwards and Cotton Mather were said to be good at haranguing. But since it must be obvious that non-profits usually survive by constantly soliciting fresh endowment funds, what would be the matter with taking a direct approach to that goal. Why not just state in advance that the institution is only intended to do its good work for say fifty years, and then it must turn its residuals over to somebody else? Not many endowments have been limited to a lifetime of fifty years, but in those who have done so, the experience seems to be that most of them immediately set about to raise additional funds to keep the institution from disappearing. The American Enterprise Institute in Washington, for example, started out dispensing about a million dollars a year; last year it dispensed over $30 million. Whether he intended it or not, the message Mr. Olin transmitted was not that think tanks are only good for thirty years. He told his executors in effect, "You have some seed capital with which to start a think tank. Whether it lasts longer than fifty years, is now up to you."

Running the Opera

|

| The Kimmel Center |

MICHAEL Bolton, Vice President of the Opera Company of Philadelphia, recently addressed the Franklin Inn Club, giving one of the more informative descriptions we have had about the inner workings of a philanthropic entertainment. We are very grateful to him for being so frank and open about an important perplexing issue.

The Academy of Music was originally designed as an opera house but served for many years as the home of the Philadelphia Orchestra as well. We formerly had two Opera companies, but the audience couldn't support two before they merged. Things are now definitely looking better for opera in Philadelphia; the recent presentation of La Boheme , for example, was one of the high points of American opera in recent memory. However, that achievement has been made with struggles and a certain amount of patchwork. For example, the Academy of Music is owned by the Philadelphia Orchestra, which now has its home in the Kimmel Center, and rents the Academy building to the Opera. It's hard to know who makes out better in this circular arrangement, but there is little doubt the Opera Company is pinched by the rental fee of $45,000 per performance, which probably partly goes to subsidize some of the financial troubles of the Orchestra that have recently been in the papers. It ends up costing a million dollars to put on a performance at the Kimmel Center, nearly two million to put one on in the Academy.

It's true that our opera costs (and ticket prices) are less than in many other cities, most notably the Metropolitan Opera in New York. But it's more important to know that only half the budget is spent on performers. When you hear of the prices paid to performers, particularly soloists, it's easy to imagine this is the main source of financial strain. But the issue is not what people are paid, but rather who is overpaid. At the top of the list has to be the stagehands, whose hourly wages Mr. Bolton declined to specify. But I recently had the opportunity to overhear a conversation on the train between a stagehand and his friends. With great glee, the gentleman described how few hours he worked, how little needed were his services, and how soon he expected to retire. Even making some allowance for boastfulness, this recital was a little hard to take on the day after I had sat in a hundred-dollar seat.

|

| The Academy of Music |

Philadelphia wants to put on more and better operas. There are so many applicants for positions that the junior nonfamous singers are charged $300 by the agents, just to have an audition. Voice teachers command several hundred dollars an hour to coach aspiring performers. There is a great oversupply of performers in the local market; the problem is inadequate demand, resulting in part from high prices. No doubt this situation will correct itself, partly, when the economy recovers. Unfortunately, however, some of us old-timers can remember the Japanese recession which is in its seventeenth year, and our own Great Depression of the 1930s, which lasted fifteen.