2 Volumes

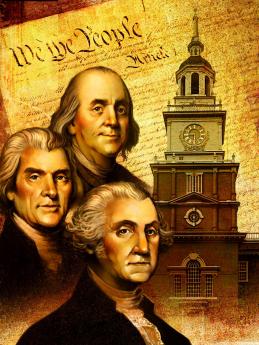

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Rt. Angle by Years

The history of Philadelphia"s finest men's club.

Right Angle Club 2012

This ends the ninetieth year for the club operating under the name of the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia. Before that, and for an unknown period, it was known as the Philadelphia Chapter of the Exchange Club.

Dear Members of the Right Angle Club,

2012 was a remarkable year at the Right Angle Club. First of all, it was our ninetieth year, the completion of another decade of eating, occasional drinking and some mild misbehavior as we soaked up the knowledge and information imparted to us on an almost weekly basis by the finest lineup of speakers in recent club memory. Recent memory may be about all we can muster at the Right Angle Club, but that does not curtail our pursuit of conviviality and good fellowship.

When I assumed the intimidating duties of President of our club, I announced to our assembled group of officers and board members that my goal for 2012 could be summed up in one three-letter word: fun. Now I realize that this may at first appear to be an appeal to our baser instincts, but I felt that fun was an element somewhat in short supply in recent years, not through anyone?s fault but the direct result of some necessary updating of our way of doing things. Now that we have all agreed to take the necessary leap from the 19th to the 21st century, I believe that the restoration of fun has been achieved.

|

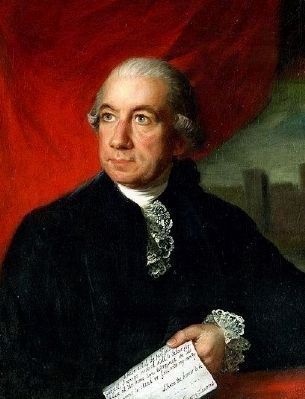

| President John Fulton |

There were two major accomplishments in 2012. First, the employment of the QuickBooks accounting system, which included the efforts of our Treasurer, Rod Rothermel along with the Finance Committee chaired by John White. Second, was the uploading of an up-to-date and printable membership directory that can be maintained and updated by the club?s able administrative assistant, Le Anne Lindsay. This effort was spearheaded by Tom Williams.

Several of our affiliate members became full members in 2012. These include Dick Pascal, Ed Ermilio, Steve Bennett, David Barclay, Howard Trauger and John Coates. New members that joined as full members in 2012 include Horace MacVaugh, Harvey Young, Dane Wells, Chad Bardone, Warren West and Olav Urheim. Several long time members have resigned, among them Dick Palmer and Jerry Leon. We wish them well and hope to see them again.

My predecessor John White came up with a way for members who may wish to remember the Right Angle in their will, The Centennial Fund, in recognition of our fast approaching one-hundreth year in 2022. The goal is far more modest than that of an endowment; it is more of a ?rainy day? fund so that we may continue operations smoothly and seamlessly in the event of a future shortfall. John has also employed his Constant Contact software to announce the Club?s special events by email, prepare a list of expected attendees and provide a system for credit card payment. Dan Sossaman was our membership chairman and his efforts in 2012 included our member-guest meet and greet event in April and the membership recruitment aspect of our annual Fall Fling, about which more in a moment. Dan will become our president at the President?s Dinner of 2013 to be held once again at the Philadelphia Club.

Jack Foltz was our events chairman and he organized three exciting affairs in 2012 that were well attended by members and their guests. The first was our annual Spring Fling, which was held on a sunny Sunday afternoon at Bartram?s Gardens. It was my first visit to this beautiful and historic site discreetly tucked away in not-so-scenic southwest Philadelphia. Next came our Fall Fling at the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum, with its priceless and dazzling collection of race cars from the past 100 years. Finally, our Christmas party was held at the stately Valley Forge Military Academy, a wonderful setting for the event. I can say with confidence that at every one of these events a great time was had by all. The Right Angle Club owes its continuation over the years in large measure to the consistent quality of our speakers program. In 2012 speaker chairman David Richards attained new heights with an outstanding line up of speakers including several members, among them David himself, John Wagner, George Fisher and Peter Alois. When one could bring a guest who is a prospective member to a luncheon where any one of this year?s speakers held forth, it makes membership in The Right Angle Club a very attractive prospect.

Carter Broach will step into the breach as next year?s speaker chairman, as David moves on to become next year?s events chairman. Carter oversaw our raffle at each luncheon in 2012, and once again, our designated charity to receive raffle proceeds is the Children?s Scholarship Fund Philadelphia. A minor disruption in the weekly venue for Right Angle Club luncheons occurred mid-year when the Vesper Club vacated its building on Sydenham Street and moved into the Grille downstairs at the Racquet Club, where we have held our luncheons since 1991. Our club continues to meet at the Racquet Club, and now does so in the Main Dining Room on the first floor. We plan to stay at the Racquet Club, and some of our luncheons may be on the second floor Bell Room.

Well, I don?t know about you, dear member, but looking back on 2012, I can say without reservation that I have had a lot of fun at the Right Angle Club. I sincerely hope that you have enjoyed it as well. I encourage those among you who wish to pursue a leadership role at the club to signal your intent to do so to one of our officers. I can assure you that the effort is very rewarding.

Boalsburg

|

| Boalsburg |

FIVE miles East of State College is Boalsburg, which is by far the most interesting place in Central Pennsylvania. First of all, the town itself is laid out around the most perfect surviving example of a Scotch-Irish diamond. The Scots in Northern Ireland were much resented by their Roman Catholic neighbors to the south of them, and gladly accepted James Logan's offer to come to William Penn's haven of religious freedom, in return for their settling near the Indians. This was Logan's solution to the problem of keeping the peace between the pacifist Quakers in Philadelphia, and the sensitivities of the Indians about settlers on their ancient lands. The Quakers wanted to avoid conflict with the Indians, wouldn't sell them either liquor or gunpowder, while Logan was under orders from Penn's descendants to sell the land. So, being Scotch-Irish himself, he felt confident his relatives would find ways of coping with the problem. Much of the turmoil of Pontiac's War and the French and Indian Wars, the marauding Paxtang Boys and King George's War, grew out of the resulting conflicts between the two notoriously combative groups. In any event, this decision explains why Scotch-Irish settled the frontier early, and surprisingly far west of the centers of Pennsylvania Dutch settlement. The Scotch Irish had a tradition of favoring the crossroads of two main highways. Their habit was to cut off the four corners of an intersection, leaving a diamond-shaped park in the middle. Traditionally, the enlarged intersection would have a flagpole in the middle.

|

| Boalsburg Diamond |

Naturally, the diamond was a good place to put a post office, a general store, or a tavern. A man named Boal put up an early tavern, and this diamond became Boalsburg. Boal is the name of a type of Madeira wine, which may have some relevance here, having to do with old stories of some Portuguese debts which were paid off in the land of Center County. In any event, there is a log cabin near the diamond, with a dozen Boal tombstones in front of it. Quite a large and elegant restaurant is now more directly on the square. This town is a photographer's dream and well worth anyone's drive around the main streets.

At some time, the Boal family moved out of the center of town to a mansion about half a mile away. From the looks of it, five or six additions were made to house family and servants, and it almost looks like five houses joined together. The carriage house has a couple of ancient carriages, one with and one without, leaf springs. The walls are hung with dozens of sabers and swords from many different wars, each with its story. There are muskets and rifles, dating back to the Revolutionary War.

The main house is modest for a mansion but immoderate for a farmhouse. It has definitely been lived in, and it's built for comfort. The walls are covered with trophies and mementos, with five signatures of US Presidents identifiable. Lots of Boals seem to have married lots of European nobility, perhaps in one of these rooms. One old rake is quoted as saying he inherited three fortunes -- and spent 'em all. Over and over again the theme emerges: the Boals was a military family, often raising their own regiments. Across the road in what seems sure to have once been Boal property, is the Military Museum, with real battleship cannons at the gate. Memorial Day was started here after the Civil War, and it is the headquarters of the local National Guard Division; it's by far the most popular tourist attraction in town.

|

| The Columbus Family Chapel |

But off in one corner of the side yard of the mansion is a little stone house, perhaps two stories high. It is a replica of the Columbus family chapel in Spain, copied stone for stone. The stories vary somewhat between guides, but apparently, two or more relatives were descended from Christopher Columbus, and while one Boal was Ambassador to Bolivia, he married a lady in waiting to the Queen who was also descended. Possibly the Spanish Civil War had something to do with it, but in any event, the personal belongings of the Columbus family were judged to be the property of the Boals, so they were moved here to the chapel replica. A decade or so ago, the chapel was broken into by thieves, and since that time security is considerably enhanced. Two pieces of wood are still shown as pieces of the True Cross of Jesus, with authentication going back to the 5th Century, and numerous handwritten journals are there. The Goya paintings and tapestries, and a solid gold crucifix are among the pieces which are now somewhere else. The matter is one of considerable embarrassment. Most of the many pieces which remain, are seeming of the nature of things which would be enormously valuable if you knew what they were, but just about worthless if you don't. In a sense, the best protection is the ignorance which surrounds them. The guide last month remembers one day when 27 visitors came to the Mansion and many days when no one came. As he spoke, you could see at least five hundred cars parked in the Military Museum across the road. There may have been five cars parked in the diamond in the center of Boalsburg. It's sort of a shame that this would be true, just as it makes you grit your teeth to imagine the indifference the whole place would receive if you moved it to Times Square. But, let's face it, the main protection for these invaluable pieces of history lies in that general lack of interest in them.

Ginseng Trading

DECLARATION of a state of war between Great Britain and its colonies almost immediately set loose some thinking about how to divert some of the profits and commercial arrangements of the British Empire to other owners. In particular, the American merchants began to consider how to capture colonial trade with China, or at least look into what useful gossip they could pick up in the many dealings with sea captains in port, or traders in their counting houses. The waterfront has always been a tough place, and in the seaside taverns, it can be particularly difficult to get trustworthy information or form dependable commercial alliances. So it is not entirely surprising if the captains and agents of Robert Morris found themselves in the company of many seafarers who later proved to be little short of pirates. England was conducting a lucrative trade with China, and the American colonies supplied much of the commodities. The Treaty of Paris suddenly transformed smuggling and near-piracy into open season for international trade, with much room for sharp practice.

On February 22, 1784, the Empress of China, a brand-new copper bottomed vessel built in Boston for a dubious trader named Daniel Parker, set sail from Manhattan for Canton. John Cleve Green was the captain, and ownership was a confused tangle of William Duer, John Holker, and a firm of Turnbull, Marmie, and Company which was essentially a disguised agency of Robert Morris, with Morris the dominant owner. The ship had a cargo of two commodities: 250 casks of ginseng, and twenty thousand dollars in silver. The ship would return from China a year later, bearing tea, silks, and porcelain. The world was in a post-war depression, and the numerous part owners of the venture were barely speaking to each other. But five years later it was recorded that 19 American vessels were tied up in the port of Canton. Just whose idea it was, and who gets the main credit for making it a success can be endlessly disputed, both inside and outside the courtroom. But this was in broadest outline, how the China trade began.

The rest of the story is mainly a botanical one.

Children Playing With Matches

|

| Playing with Matches |

THERE are still a lot of people secretly re-fighting the Vietnam War, which in retrospect was rebellion against the draft and allegiance to the idea that America just doesn't start wars. But times change, and those who now suppose the secret sympathizers with the anti-draft movement will automatically join a second call to rebellious duty, are probably going to be disappointed with how conservative the baby boomers have become. The boomers find themselves parents, defending their own authority from attack by their children. As King Lear ruefully observed in the same reversed situation, let them feel how sharper than a serpent's tooth it is, to have a thankless child. We now define our present world problem as overleveraging, not compulsory military service, and estimate it may take as long as fifteen years to sort itself out -- until yet another judgmental generation comes over the hill behind the rebels. The aggregate debts of the European Union, using present-value calculations, are said to be three times as large as the Gross Domestic Product of Germany; now, that's really a problem. When you consider the only sure cure for excessive leverage is "growth", and that the code word of growth really means stuff wearing out, getting used up, and getting obsolete, it is not hard to see it taking 15 years to go away -- much more lasting than any draft dodger issue. When I go to restaurants they are crowded and expensive; people are living on their reserves, but there seem to be lots of reserves so this problem will last a long time.

But, four generations back, I can remember 1937 when there were no reserves, and plenty of homeless people actually froze to death. Plenty of people were then talking Communist who nowadays are talking McCarthyism, hoping no one notices the switch. I used to ride up and down the elevator of a hospital with Harry Gold, the thermonuclear spy no less. So what worries me about the present uproar is that it comes too soon, before very many people get really scared enough to do really stupid things, then recognize their folly.

I think it was Abbie Hoffman, not Jerry Rubin, who climbed up into the visitors' gallery of the New York Stock Exchange and threw handsful of dollar bills, salted with just a few hundred-dollar bills to bring trading to a halt. Big joke; just see who was scrambling on the floor. That's what the sixties seemed like to most of us; a big joke. But out at Kent State, some kids with crew cuts were information, under orders that at the last moment the gun barrels must come level -- and the live rounds slide home.

Tammany: Philadelphia's Gift to New York

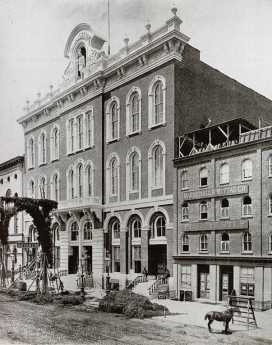

|

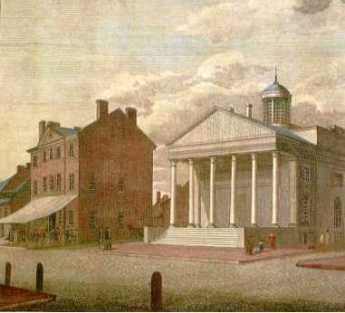

| Tammany Hall |

EDWARD Hicks painted a scene over and over, depicting William Penn signing a treaty of peace with the Lenape Indians at Shackamaxon ( a little Delaware waterfront park at Beach Street and E. Columbia Ave.). This scene was apparently a reference to a larger and more finished depiction by Benjamin West. The Indian chief in the painting is Tamarind, chief of the Delaware tribe. Long before Hicks got the idea for the picture from Benjamin West, Tamarind was locally famous for having the annual celebrations of the Sons of St. Tammany named after him. These outings centered on the joys of local firewater and thus may have had something to do with the evolutions of the Mummers Parade. George Washington presided over a lively Tammany party at Valley Forge, and local Tammany Hall clubs sprang up all over the country. The most famous offshoot had its headquarters on 14th Street in New York, as a club within the local Democrat party asserting Irish dominance over New York politics, allegedly using Catholic Church connections to control other immigrant groups. The identity of Tammerend seems to have got thoroughly mixed up along the way; the famous statue of "Tecumseh" at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, much revered by the cadets, is actually a depiction of Tammany.

|

| Penn's Treaty With the Indians By Benjamin West |

At earlier times, Tammany was the vehicle Aaron Burr used to assert control of the now-Democrat Party, particularly in the contested Presidential election of 1804. Shooting Alexander Hamilton in a duel, along with disgrace and impeachment as Vice President necessitated Burr's rapid conversion into a non-person, both in New York and in Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, the uproar led to the dispersion of Tammany influence, while in New York other bosses, particularly Boss Tweed, took over the organization and consolidated its role as a small club which dominated a larger political party, which in turn pretty well took over the government of New York City, which in turn dominated the governance of New York State, and even occasionally leveraged itself into national politics. Eventually, Tammany fragmented sufficiently that Mayor Fiorello La Guardia was able to dislodge it from control, which in time led to its dissolution. In a larger sense, however, the decline of New York's Tammany Hall began when in the late 19th Century it adopted the Philadelphia system of consolidating graft from local leaders into unified "donations" from local utilities. That greatly improved the efficiency of collections and disbursements but undermined the need for an effective local organization of ward leaders.

|

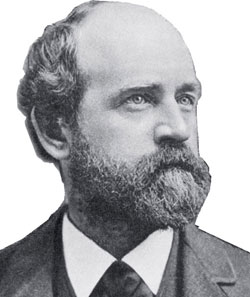

| Aaron Burr |

So, although Tammany was originally a Philadelphia creation perfected by New York, it continued to have connections to Aaron Burr in early days, and Philadelphia machine politics later on. But of course for seventy-five years, around here it seemed Republican.

Bonds--Do They Have A Future?

|

| Relic of the Past? |

EVER since we finally went off the gold standard completely during the Nixon Administration, the Federal Reserve has adjusted our money supply to create a fairly steady 2% inflation. If inflation is ever less than 2%, the Fed puts more money into circulation. Since many bonds are paying less than a 2% dividend, everybody who buys and holds them at par will lose money in "real" terms. That is, everyone who buys bonds when they are issued and sells them when they mature will lose spending power. Since they fluctuate in the meantime, it is possible for a trader to buy them when they are undervalued by the market. That trader will possibly make money, but only because someone else lost money. Something like that occurred during the recent financial crash bailout, when interest rates declined from 3% to less than 2% but were repurchased by the Fed as "Quantitative Easing", effectively giving speculators a 33% profit at government expense. But that doesn't happen often, and just guess who ultimately lost the money the speculators made. There is also that daunting question: when the time comes for the Federal Reserve to disgorge them, just who is going to buy all these cheapened bonds? In Japan, bonds paid a dividend of less than the rate of inflation for more than a decade; it's hard to think of a reason why the same thing could not happen in America. So it's also hard to imagine a reason why buy-and-hold investors should not abandon bonds, perhaps suddenly all at once, at some unknown time in the future. At that point, many of them will resolve never to try that, again. The whole idea is troubling.

It's particularly troubling in view of the lack of success, so far, of TIPS. These vehicles are new; perhaps the algorithm is set to ignore minor inflation and will over-respond to more major inflation, ultimately rewarding those who buy them. But at least so far, they are a disappointment. Furthermore, TIPS are quite cleverly designed to be inflation-protected, while unfortunately inflation usually does not follow a straight line but is volatile, or saw-toothed; the jury is still out. The jury better hurry up, because all investors look for net income after expenses, which include brokerage costs, taxes, and inflation. A long-term bond might have to pay a dividend approaching 4%, just to emerge with the same net value it started with; after five years of 4%, you could be 20% behind. And yet, the bond market with or without inflation protection is far larger than the stock market and compares in size with all other kinds of market. Who buys them, especially in these huge quantities?

Somebody must maintain statistics which answer this question, but as a guess, the main buyers are insurance companies, endowments, annuities, hedge funds, banks. And foreigners, of course, to whom our follies seem trivial compared with their own. The great argument for bonds is the safety of principal, and although safety is in question anywhere there is inflation when the topic is cash flow, safety is definitely an issue. Cash shortages are what cause bankruptcies, which are mainly useful in providing time to liquidate underlying wealth to pay restless creditors. The management of a non-profit organization must meet its payroll out of cash flow, so non-profits protect themselves from dissolution by having a regular flow of nominally secure bond dividends. Income from donations and contributions can be particularly weak during times of economic stress. Since most for-profit organizations also experience variable periods of time without profits, their situation does not differ greatly from nonprofits. That's particularly true when a for-profit organization has a vocal, activist stockholder group, who will protest fiercely if the management retains abundant cash. For such a predicament, holding bonds creates safety by some definition. The price of that safety is the long-term average loss on the bond portfolio; the company's alternative losses are whatever it takes to maintain a stable work force during unstable times. The business school assessment of this tradeoff is that bond losses can usually be passed through to the customers as a business cost, while layoffs and strikes may not be.

To restate the characteristics of willing bond purchasers, they are governments and corporations who have no common stock issuance alternatives, but regularly face a need to have money available for payroll. They also include borrowers and lenders at nominal interest rates like banks and insurance companies, who can afford to ignore inflation because their own liabilities are in nominal dollars, or come due at a date certain. And then, there are a host of beneficiaries of special-interest bond provisions, like "Flower bonds", state and municipal governments, foreign aid, student aid, etc. As an overall statement, natural bond buyers are those who either do not possess steady equity (common stock) alternative to offer investors or else are shielded in some way from the inflation and tax costs of buying bonds. Speculators and traders are excluded from the discussion because fixed-income trading is a zero-sum game, something you should teach your children to avoid. Other than these special niche opportunities, bonds should be regarded by the ordinary investor as trading opportunities when interest rates get too high, which is roughly every fifteen years or so.

Things in the bond market were not always so bad; Robert Morris, Jr. was a genius for devising this market in 1784. But the equity market was then not so well developed, life expectancies were shorter, and a minimum 2% inflation was not guaranteed by the Federal Reserve. The income tax had not been invented. It was possible to enjoy the promised benefits of lending in those days, for decades or even lifetimes. It was much harder to find investments of superior performance, without getting involved in business management. Meanwhile, the bond market just got huger and huger. Modifying or dismantling it in logical ways would have enormous disruptive effects. So enormous, the Congress has just adopted the stance called "kicking the can down the road", which is a debt you never seriously intend to repay.

Are we waiting for the bond market, the bond vigilantes, or speculators to find some vital vulnerable flaw, and topple it all into the ashcan of history? Or is there some better plan that no one has mentioned?

Relocation

|

| Moving Truck |

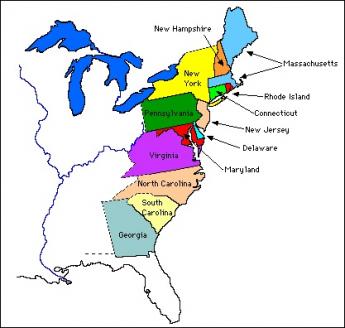

For many decades, at least since the Second World War, the Northeastern part of the country has been losing population. And business, and wealth. In recent years, New Jersey has been the state with the greatest net loss, and the Governor who is making the greatest fuss about it. Statisticians have raised this observation to the level of proven fact, although lots of people are even moving into New Jersey at the same time. This is a net figure, and it remains debatable what sort of person you would want to gain, hate to lose; so it's hard for politicians to be certain whether New Jersey's demographic shifts are currently a good thing or a bad thing.

Take the prison population, for example. Most people in New Jersey would think it was a good thing if the felons all moved to some other state because it would imply less crime and law enforcement costs. But one of the major recent causes of a decline in violent crime seems to be the universal presence of a portable telephone in everyone's pocket. Just let someone yell, "Stick 'em up!" loud enough, and thirty cell phones are apt to emerge, all dialing 911. On the other hand, cell phones are the universal communication vehicle for sales of illicit drugs and other illegal recreations, and the increase in automobile accidents is a serious business for inattentive drivers. Add to this confusion the data that capital punishment is more expensive for the State than incarceration is, and you start to see the near futility of knowing what is best to have more, or less, of.

What the Governor and his Department of Treasury mostly want to know is whether certain taxes end up producing a good net revenue for the State. That is, whether more revenue is produced by raising certain taxes more than others, or whether some taxes are a big component of the Laffer Curve, causing revenue to be lost by driving business, or business owners, out of state, in spite of the immediate revenue gain. The studies which have been done are fairly conclusive that executives tend to be most outraged by property taxes, since they have a hidden effect on the sale price of the house, and the amount of money available for school improvements. At least at present levels, a Governor is better off taking abuse for raising income or sales taxes, even though the apparent tax revenue might be the same as a rise in property taxes. Since property taxes are mostly set by a local municipal government, while sales and income taxes are usually set by state governments, a decision to raise one sort of tax or another can have unexpected consequences, or require obscure manipulations to accomplish.

Some politicians who believe their voting strength does not lie in the middle class, would normally want to hold up property values, not taxes because the data show that higher home prices drive away from the middle class and in certain circumstances are positively attractive to wealthy ones. Higher prices appeal to home sellers, at least up to a point. Wealthier people who are buying houses are likely to have an old one to sell; that's less true of first-time home buyers or people presently renting. Certain issues can even be reduced to rough formulas: a 1% increase in income tax would cause a 1% loss of population, but a 5% loss of people earning more than $125,000. A $10,000 increase in average home prices, on the other hand, causes a net loss of population, but mostly those with lower income. One important feature of tinkering with average home prices and property taxes is that these effects are "durable" -- they do not fade away over time.

|

| Laffer Curve |

New Jersey is financially a bad state to die in, but the decision to move to Delaware, Florida or Texas is often made over a long period of years in advance of actually doing it. It has been hard to compile statistics relating changes in inheritance tax law to net migration of retirees and to present such dry data in an effective manner to counteract the grumblings that rich people are undeserving of tax relief, or dead people are unable to complain. But rich old folks are very likely to own or control businesses, and if you drive them out of state, you may drive away a considerably larger amount of taxation relating to the business in other ways. This is the underlying complaint of Unions about Jobs, Jobs, Jobs; but state revenue also relates to sales taxes of the business, business taxes, employee taxes, real estate taxes on the business property, etc, etc. Sometimes these effects are more noticeable in the region they affect; the huge population growth of the Lehigh Valley in recent years is mainly composed of former New Jersey suburbanites, who formerly earned their income in New York. The taxes of three different states interact, in places like that.

The audience of a group I recently attended contained a great many people who make a living trying to persuade businesses to move into one of the three Quaker states of the Delaware Valley. The side-bar badinage of these people tended to agree that many of the decisions to relocate a business are based on seemingly capricious thinking. The decision to consider relocation to the Delaware Valley is often prompted by such things as the wife of an executive having gone to school on the Main Line. Following that, the professional persuaders move in with data about tax rates, average home prices, and the ranking of local school quality by analysts. Having compiled a short list of places to consider by this process, it all seemingly comes back to the same capriciousness. The wife of the C.E.O. had a roommate at college who still lives in the area. And she says the Philadelphia Flower Show is the best there is. So, fourteen thousand employees soon get a letter, telling them we are going to move.

And, the poor Governor is left out of the real decision-making entirely, except to the degree he recognizes that home property taxes have the largest provable effect on personal relocation. And lowering the corporate income tax has the biggest demonstrable effect on moving businesses. But the largest un-provable effect is dependent on the comparative level of the state's inheritance tax.

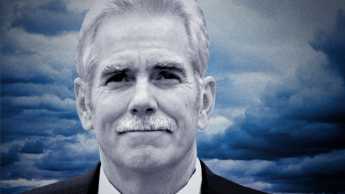

Weather Man

|

| Paul Walsh |

PAUL Walsh, our local weatherman, recently addressed the GIC (Global Interdependence Center) at the Federal Reserve, and presumably because everyone talks about the weather, the meeting was well attended. While he is too experienced to get drawn into a global warming controversy, we get the general outline of his views. What we call the weather is largely a result of various clouds and wind currents blowing around the planet in response to the rotation of the planetary mixture of oceans and land masses. The familiar landscape visible to astronauts makes it easy to accept this view of things.

The global warming issue, however you explain it and where ever it may be going, is a weather cycle to be measured in centuries. Shorter cycles of about eight years in duration tend to result in American weather patterns sometimes blowing Canadian cold air toward the East Coast, and sometimes blowing California winter weather Eastward. In 2011-12 we seem to be experiencing a California winter, while the preceding two winters were unusually cold, reflecting Canadian conditions. What may or may not be happening with the hundred-year global warming cycle is not easily slipped into our daily conversations. It is probably quite irrelevant to global trends whether or not last year was a cold one, or whether our sidewalks are unusually slippery this morning.

Inquiries about the weather are the number one topic to be clicked on the Internet, reaching 17% of queries. That's nearly double the second largest category and four times the number of inquiries about the stock market. Ordinary variations of the weather have been calculated to have an economic value of $384 billion, or 3.4% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Insurance claims for more severe weather abnormalities run between ten and fifty billion dollars a year. The number of hurricanes and similar disasters is highly variable, sometimes running as high as fifty in a bad year.

Predictions are improving, but ridicule of weatherman errors is still highly embarrassing to the professionals in the business. A generation ago, it was almost impossible to get a one-minute warning of an approaching tornado, but nowadays we average fourteen minutes warning for them. That's almost long enough to be useful. Hurricanes seem to be increasing in frequency, but decreasing in average intensity. But insurance claims are getting steadily higher, largely because more people are building more structures in harm's way.

Small wonder that weathermen are a cautious lot about predictions. The present party line, in case you wanted to ask, is that predictions more than ten years in advance -- are just about impossible.

Poor Richard's Wealth

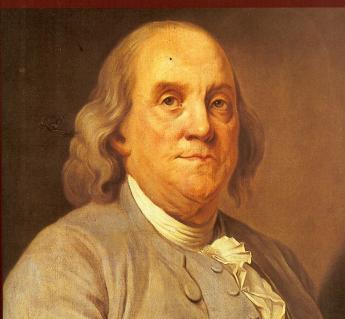

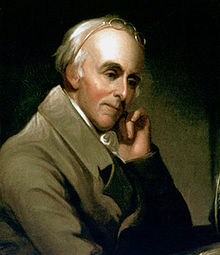

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

I RISE to offer yet another toast to Benjamin Franklin. Like our two leading candidates for the Presidency of the United States, he leaves us uncertain whether he was a rich man pretending to be poor, or a poor man pretending to be rich. To clarify this mystery, I have mainly examined the circumstances of his retirement, and the contents of his last will and testament.

Although he reports that on arrival in Philadelphia at the age of seventeen, he spent his last pennies on a loaf of bread, he was able to retire from the printing business at the age of forty-two, planning to spend the rest of his life as a gentleman at ease. He was able to do so because he had assembled over fifty partners in the printing trade, scattered from Boston to Georgia; today, we would say he had sold franchises to his business. When he came to retire, he arranged to be paid off in eighteen installments, which ought to have lasted him to the age of sixty. That was well past the usual life expectancy at the time, but we can now see it would apparently have run out while he was still in London, acting as our ambassador to Parliament, leaving him without support for the last twenty-four years of his life. Apparently, this was the reason for his seeking postmasterships and acting in some overseas business capacity for Robert Morris, then one of the richest merchants in America.

Assuming he may have run out of money when he was sixty, we look to his final estate to see how he made out in his second career, whatever it was. His assets were in three general categories: land, bonds, and hard money. He bequeathed eleven houses, mostly in Philadelphia, to various relatives. He assigned the ownership in thousands of acres of land in Nova Scotia, Georgia, and Ohio. Just what a bond was in Eighteenth-century America is not exactly clear, but bonds of at least ten thousand pounds sterling were distributed, as well as ten thousand pounds of hard assets. And he forgave a large and undefined number of unpaid debts.

He gave George Washington his gold-handled cane, which had been given to him by Duchess Du Pont, for unknown reasons. His modesty was famous but can be questioned when he gave one of his portraits to be hung in the Council Room of the government of Pennsylvania. He gave his sister a portrait of a French King, with four hundred and eight diamonds set in its frame. He instructed her not to make the diamonds into jewelry because that would be ostentatious. And he instructed that his funeral be plain and simple, although it turned out to be one of the most elaborate parades and ceremonies of the age.

After a few months, Franklin reconsidered his will and wrote a famous codicil. Revoking the gifts to his grandchildren, he ordered that a thousand pounds be set aside for each of the cities of Boston and Philadelphia. His proposal was that this money is loaned to graduating apprentices in order to help them start their businesses, and after a hundred years he envisioned it would amount to hundreds of thousands of pounds; after two hundred years, it would be worth millions and could be used for public improvements. These funds were indeed established and the loaning did begin. Unfortunately after hardly fifty years had elapsed, so many apprentices had failed to repay their loans the experiment was discontinued. What had seemingly been lacking was sufficient will of the trustees to collect the loans with vigor.

Poor Richard may have been born poor at more than one time. But he certainly didn't stay poor, very long. A toast to Ben Franklin, on his birthday, in his club.

Ben's Little Legacy

|

| Benjamin Franklin and George Washington |

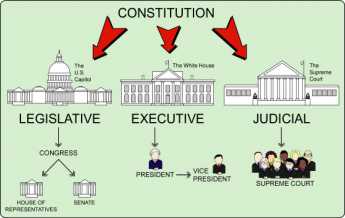

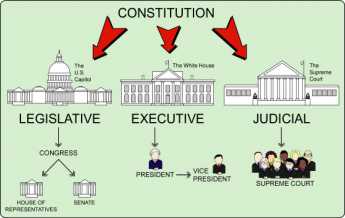

ONE of the many compromises of the Constitutional Convention was to allow equal-sized blocs of people to choose their Representatives, but the State Legislatures of any size to appoint two Senators, in a bicameral Congress requiring affirmative votes from both bodies, for action. This was the first step in a separation of powers. After separation came apportionment: every state still got two Senators, but varying numbers of Representative districts would reflect population changes. The effect of this second step was to confer greater Senate power to small states because otherwise, a few states with large populations would probably always dominate the voting. (Shorthand for Constitutional scholars: favoring the House of Representatives means favoring big states.) When Franklin proposed a bargain to give the South time to solve its slavery problem, he needed to maintain balance. The small states were truculent about losing Senate power, so he had to give something else to the big states. The three big states of Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia were very mindful that England had primarily targeted Boston, Philadelphia, and Yorktown for attack during the Revolution. Big states are paradoxically more anxious to unify with allies, to gain military strength, because enemy commanders seem to favor them as military objectives. Franklin's proposal was to allow the big states to control tax legislation, through the device of mandating that tax laws must originate in the House of Representatives. He may have known that eight states already had similar laws, but may not have realized such laws were regularly flouted. It's hard to be sure what Franklin knew because although he had once been Speaker of the Pennsylvania House, it was during a time it was a unicameral Legislature.

ARTICLE 1, Section 7. All bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives, but the Senate may propose or concur with amendments as on other Bills.

|

| Washington's Gift to Franklin |

Experienced politicians in the Convention snorted with disgust. There were a dozen ways to get around such a provision, and nowadays the traditional one is for the Senate to attach a tax amendment to some bill which had originated in the House. Any House bill will suffice, and thus we have Senate-originated Medicare Amendments attached to House-originated bills whose first page purports to be legislation about highway construction. Medicare, don't you see, is an amendment to Social Security, which itself began as tax legislation. Any politician of standing could see his way through that. And even in 1787, the delegates could immediately think of ways to circumvent this little trick. When Chairman Rutledge of South Carolina returned his report from the Committee on Detail, it included Franklin's gift to the big states. His fellow delegate from South Carolina Charles Pinckney immediately proposed a friendly motion to delete the rule. Edmund Randolph of Virginia however, felt the big states "should at least get what they had been promised", thereby upsetting others who felt Randolph was being indelicate. So George Washington stepped out of the shadows and supported Randolph, his long-term neighbor, and friend in the Virginia caucus. The matter was then referred to the Committee on Postponed Parts. After a decent interval, it was reported out of the second committee and adopted. After all, with Washington and Franklin as supporters, it would be embarrassing not to pass an inconsequential motion.

Two Friends Create the Articles of Confederation

|

JOHN Dickinson had been highly critical of England's treatment of its colonies. As early as 1768 he had written a book called Letters of a Pennsylvania Farmer which is credited with strongly influencing the colonies in the direction of resistance to the British Ministry. When it came time to write the Articles of Confederation, Dickinson was the lawyer selected for the task. His good friend Robert Morris had been less outspoken in opposition to the Ministry's behavior, quite possibly because he was adept at finding workarounds for his own personal business problems. But possibly he was merely maintaining an ambiguous negotiating posture, since in a hotly contested election with this as the main issue, Morris was elected by both sides in the argument. When July 4, 1776, forced the issue both Dickinson and Morris had refused to sign the Declaration, but within a few months both of them were actively fighting for the Rebellion. The truest test of their evolving attitudes might have emerged when Lord North sent the Earl of Carlisle as an emissary after Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, offering peace with a sort of commonwealth status for the colonies. Not much is written about this curious episode, leaving it unclear whether the British were serious, and even if they were, whether the Americans understood the offer as serious. On the surface, the British offer conceded taxation with representation as the rebellion had been demanding. But it was rejected by Gouverneur Morris acting for -- who remains unclear. It seems possible the British were exploring the true feelings of people like Dickinson and Robert Morris but were disappointed. The earlier treatment of Ireland after it had agreed to a similar half-hearted autonomy did leave British sincerity in legitimate doubt.

|

| Thirteen |

The thirteen colonies had united to fight the British King, but many of them were reluctant to unite for any other time or purpose. Rhode Island was perhaps the extreme example of this view of what Independence was supposed to mean, but the feeling existed to some degree in many colonies. Concern for the power of this feeling of tentativeness may have contributed an important reason the Articles placed heavy emphasis on declaring the document to represent a perpetual arrangement. Recognition of the weakness of this intent may have been an important reason why George Washington was later willing to sweep the issue aside, even though he of all people was most concerned to avoid the appearance of acting as an arbitrary king. For these and other reasons mainly revolving around state boundary disputes, the Articles remained unratified for years. Finally, in 1781 Robert Morris became convinced that failure to ratify was encouraging the states not to cooperate, and successfully pushed ratification through its steps. At that time, Morris was effectively running the country, even providing his own credit and funds to do it. People were reluctant to oppose his wishes, but they were also unwilling to provide the taxes, supplies, and troops that Morris imagined were being blocked by failure to ratify. Ratification of the Articles accomplished very little except to convince Morris: the Articles were flawed and must be replaced with something conferring more central power.

|

| The Goal: 1787 |

Little is known about the evolution of Constitutional thought in Morris' mind between 1781 and the Constitutional Convention in 1787, although a great deal is known about his other numerous activities. It is clear, however, that his experience with the recalcitrant Pennsylvania Legislature had been dismal, while he came to see the one insurmountable flaw in the current Federal government was its inability to levy taxes and consequently, to service national debt. The states were able to levy taxes under the Articles but erratic in doing so, resorting to paper money inflation at the first sign of tax resistance. In Morris' view, the key to the effective government was to reverse the situation; let the national government tax, let the states spend. The key to such rearrangement would be to permit the national government to spend on a very limited list of vital purposes, but bedazzle the states with a substantially unlimited shopping list if they thought they could afford it. As the accounts to pay for the Revolutionary War totaled up, it was apparent that the National Government had twice as much debt as the states. Therefore it would at most, need twice the state taxing power to service such a debt; presumably, wars would be infrequent and it would be less than that. Pay this one off, and potentially the need for future federal spending would be small. Indeed, under the presidency of James Monroe, the national debt was completely paid off, although briefly. It was almost as if Robert Morris and his pupil Alexander Hamilton had a crystal ball.

|

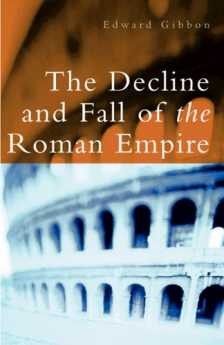

| Decline and Fall, Anyone? |

Robert Morris was brilliant and had six years to fashion his strategy, but he also had some help. For one thing, George Washington lived next door much of that time. By then, almost no one dared confront Washington. Adam Smith had written his book The Wealth of Nations in 1776, and Morris gave this extraordinary work as presents to his friends. Morris had corresponded with Necker, the genius financier of France, and through his good friend Benjamin Franklin, gathered insights from the rather advanced British national finance. And James Madison brought in scholarship about politics and statecraft accumulated by Witherspoon, Hume and the Scottish enlightenment. The year 1776 was a remarkable moment for new ideas. In that year, Edward Gibbon also published the first volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The warning behind that important book had an important impact on the minds of important thinkers of the era, too.

Once you grasped all the central ideas, in this environment the resulting strategy almost worked itself out.

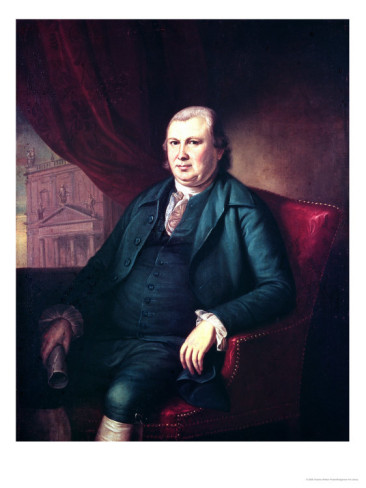

Penman of the Constitution

|

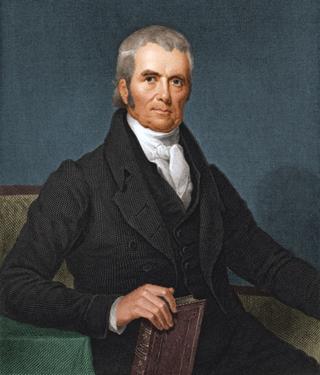

| Gouverneur Morris |

THE Constitution is the product of many minds, its ideas have many sources. But final phrasing of the unified document can largely be traced to a lawyer, Gouverneur Morris. The Constitutional Convention would announce a topic, argue for days about different resolutions of it, and then vote on or amend a composite resolution ( unless the matter was deferred to another day of earnest wrangling.) After months of deliberation, that jumble of resolutions made quite a pile. The Convention then turned it all over to Gouverneur Morris for smooth editing and uniformity. Although Morris had arrived a month late for the Convention, he still had time to rise and speak his views more than any other delegate, 173 times. But comparatively few of his ideas identifiably survived the voting; by Convention's end, the delegates were most likely listening for elegance and poise, increasingly expecting the final edit to be his. He finished the task in four days, and the full convention only changed a few words before accepting it. This assembly needed a lawyer who would sincerely follow the intent of his client, rather than yield to the slightest temptation to warp it with his own views. The convention had heard his opinion about almost everything, were thus alerted to uninvited slants. He gave them what they asked for, wording it for persuading the nation, as he himself had been persuaded by what the delegates wanted. The remarkable degree to which he had faithfully served his client's wishes, rather than his own, only emerged twenty years later. During the War of 1812, he disavowed the Constitution he had written.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

|

| Preamble to the Constitution |

Morris mostly shortened what the delegates had said. A word here, a phrase there, sometimes whole sentences were removed. After that, rearrangement, and substitution of more precise verbs. This lion of the drawing room, this duelist of the salon, undoubtedly had an enjoyable time twitting his less accomplished clients with brisk capsules of what, of course, they had meant to say. To remember that he was outshining Benjamin Franklin and most of the other recognized wits of the continent, is to savor the fun of it all. Of all people in the Enlightenment, Franklin was certainly Gouverneur's equal in sparkling exchanges of debate. Here, he did not even try.

|

| John Peter Zenger |

Where did this apparition come from? He was almost but not quite a lord of the manor, referring to his extensive riverfront estate in the Bronx called Morrisania, which dated back seven generations in America and ultimately belonged to him, but the title went to his half-brother. He was unquestionably a member of that small society which settled America before the English colonization. Even George Washington was only a fourth-generation American. The Morris side of the family had included two Royal Governors of New York, including the one who tried to imprison Peter Zenger for telling the truth. Gouverneur was his mother's family name, one of the Huguenots who settled New Rochelle in 1663. Under the circumstances, it is not surprising that his mother was a loyalist, and his half-brother a Lieutenant General in the British Army. Gouverneur Morris was a brilliant student of law, unusually tall and handsome for the era. He was as tall as George Washington, and Houdon used him as a body model for a statue of the General. Among the ladies, he created a sensation wherever he went. At an early age, however, he spilled a kettle of hot water on his right arm, which killed the nerve and mummified the flesh. The pain must have been severe, with not even an aspirin to help, and the physical deformity put an end to a big man's dreams of military valor. To a young mind, the physical deformity probably seemed more disfiguring than it needed to be, in addition to diminishing his own ideas of himself. He turned to the law, where he was probably a fiercer litigant than he needed to be. And more of a rebel.

The timing of circumstances drove him out of Morrisania, then out of Manhattan, as the invading British cleared the way for the occupation of New York City. Then up the Hudson River to Kingston, and on to the scene of the Battle of Saratoga. He had been elected to the Continental Congress but stayed in the battlegrounds of New York during the early part of the Revolution, helping to run the rebel government there, and making acquaintance with George Washington, whom he soon began to worship as the ideal aristocrat in a war he could not actively join as a combatant himself. With Saratoga completely changing the military outlook for the rebellion, Morris was charged up, ready to assume his duties as a member of the Continental Congress. By that time, Congress had retreated to York, Pennsylvania, George Washington was in Valley Forge, and the hope was to regroup and drive the British from Philadelphia. For all intents and purposes Robert Morris the Philadelphia merchant, no relative of Gouverneur, was running the rebel government from his country home in Manheim, a suburb of Lancaster. After presenting himself to Robert, Gouverneur was given the assignment of visiting the camps at Valley Forge and reporting what to do about the deplorable condition of the Army and its encampment. By that time, both the British and the French had about decided that the war was going to be decided in Europe on European battlefields, so the armies and armadas in America were probably in the wrong place for decisive action. Lord North had reason to be disappointed in Burgoyne's performance at Saratoga, and Howe's abandonment of orders, even though by a close call he had captured the American Capital of Philadelphia. Consequently, Lord North added the appearance of still another defeat by withdrawing from Philadelphia, deciding in the process to dispatch the Earl of Carlisle to offer generous peace terms to the colonies. Carlisle showed up in Philadelphia and was more or less lost to sight among rich borderline loyalists of Society Hill like the Powels. His offer to allow the Americans to have their own parliament within a commonwealth nominally headed by the Monarch went nowhere. The Colonist Revolutionaries were being offered what they had asked for, in the form of taxation with representation. To have it more or less snubbed by the colonists was certainly a public relations defeat to be added to losing Philadelphia and Saratoga. In this confused and misleading set of circumstances, Gouverneur sent several official rejections of the diplomatic overture and wrote a series of contemptuous newspaper articles denouncing the idea. It seems inconceivable that Gouverneur would take this on without the approval of Washington, Robert Morris, or the Continental Congress, to all of whom he had ready access. But if anyone could do such a thing on his own responsibility, it was Morris. One hopes that future historians will apply serious effort to clarifying these otherwise unexplainable actions.

With of course the indispensable help of retrospect, some would say Gouverneur Morris had committed a massive blunder. The Revolutionary War went on for six more years, the Southern half of the colonies were devastated, and the post-war chaos came very near destroying the starving little rebellion. The alternative of accepting the peace offering might have allowed America and Canada to become the world powers they did become; but the French Revolution or at least the Napoleonic Wars might never have happened, the World Wars of the Twentieth century might have turned out entirely differently, and on and on. Historians consider hypothetical versions of history to be unseemly daydreams ("counterfactuals"), but it seems safe to suppose Gouverneur Morris changed history appreciably in 1778. Whether he did so as someone's agent, or on his own, possibly remains to be discovered in the trunks of letters of the time. Whether the deceptive atmosphere of impending Colonial victory was strong enough to justify such wrongheaded decisions, is the sort of thing which is forever debatable.

While most of the credit for the style of the Constitution must go to Gouverneur Morris, there is a record of a significant argument which Madison resisted and lost, about the document style. During the debates about the Bill of Rights, Roger Sherman of Connecticut rose to object to Madison's intention to revise the Constitution to reflect the sense of the amendments, deleting the language of the original, and inserting what purports to be the sense of the amended version. That is definitely the common practice today for organization by-laws and revisions of statutes; it is less certain whether it was common practice at the end of the 18th Century. In any event, Sherman was violently opposed to doing it that way with amendments to the Constitution. After putting up a fight, Madison eventually gave up the argument. So the 1789 document continues to exist in its original form, and the fineness of Morris' elegant language is permanently on display. It may even help the Supreme Court in its sometimes convoluted interpreting the original intent of the framers. In any event, we now substitute the unspoken process of amending the Constitution by Supreme Court decision, about a hundred times every year. By preserving the original language, the citizens have preserved their own ability to have an opinion about how it may have wandered.

REFERENCES

| Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris, the Rake Who Wrote the Constitution : Richard Brookhiser: ISBN-13: 978-0743256025 | Amazon |

What Is the Purpose of a National Constitution?

|

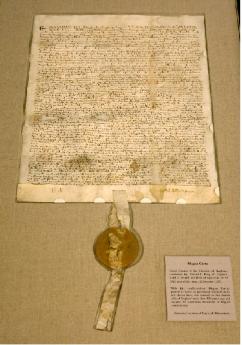

| 13th Century Magna Carta |

NATIONAL constitutions are mainly an outgrowth of the 18th Century Enlightenment, even though similar features are to be found among ancient legal codes. Those who trace the origins of the American constitution to the 13th Century Magna Carta will usually point to a central sentence of clause 39:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

|

| American Constitution |

That's a pretty good beginning, a good example of a needed legal principle, but unrecognizable as what we would today call a Constitution. It states what a government may not do, but does not define the nature of a government which does the job best. Nor do even the many Enlightenment philosophers of government take that final step of outlining where their notions should take us until the American Constitution had been written and defended in the Federalist papers. Nowhere among the writings of Montesquieu (The Spirit of the Laws, 1748), Catherine the Great (Nakaz, Instructions to the All-Russian Legislative Commission, 1767), Diderot (Observations About Nakaz, 1774), James Madison (1787), John Dickinson(1763) or Gouverneur Morris(1787) can there be found much tightly described definition of a constitution. Certainly, there is no definition within the writings of Adam Smith if we look for rule-making among Enlightenment thinkers whose ideas were influential on the 1787 Philadelphia document. The American constitution was the product of many minds, before and after 1787. The outlines of its final form converged, and emerged, from the Constitutional Convention of the summer of 1787, with Gouverneur Morris as the penman of record. To him, we certainly owe its succinctness, which is the main source of affection for the document. That probably understates matters; in his diary of the secret meetings, James Madison records that Gouverneur Morris rose to speak about 170 times, more than any other delegate. Lots of thought and debate; ultimately, few words.

The Elizabethan Sir Francis Bacon has the greatest claim on devising a theory of law and law-making in the Anglosphere tradition. But his elegant modification of Galileo's scientific method, the English Common Law, is more a methodology for creating good laws than an outline of a nation's legal principles. Anyway, tracing the American Constitution back to an underlying British one tends to stumble when the British Constitution fails to meet a definition which would include our own. The British Constitution is said to be "unwritten" to the degree it is a consensus of revered documents. It can be amended by Parliament at will, has a variable history of defining just who is covered by it, and in order to define constitutional principles seems to rely on sentences extracted from difficult context. If the two constitutions had been written and compared at the same time, one would say the British had sacrificed coherence out of respect for tradition. In fairness, some features of the American constitution are also perhaps unnecessary for every constitution, but by surviving as the oldest constitution of the modern form, have become its model. That would be:

A set of principles governing the legitimacy of a nation's laws, and firmly standing above them. It defines its own domain, geographically and by the membership of a defined citizenry. Except as otherwise defined, it supersedes all other governance within its domain. It defines and defends its own origins. It includes a description of how to amend it, which is intentionally infrequent and difficult. It goes on to outline the structure of the laws it regulates, with subtle modifications made to channel the type of power structure which will govern.

In the American case, history and culture generated several other instabilities so central they justified heightening the difficulty to amend them to a Constitutional level, thus conferring undisputed dominance over competing principles of governance. That would be:

A separation of government powers weakened all potentially offending branches of government, and thus enhanced citizen liberty. Separation of church from state, for like purpose. A right of citizens to bear arms, to strengthen citizens' defense against internal or external attack, and perhaps also warning that revolt must be possible, even endorsed, as some final extremity of protection for citizen sovereignty.

|

| Russia's Catherine the Great |

It enhances our comprehension to contrast the outcomes of competing 18th Century implementations of the Constitution idea. Russia's Catherine the Great proposed a constitution steeped in the traditions of the Enlightenment but ultimately designed to define and strengthen the role of the monarch. Denis Diderot her French protege recoiled at this viewpoint, substituting other views resembling those of Jean Jacob Rousseau. He opened Observations About Nakaz his commentary to the Queen, with the following declaration:

There is no true sovereign except the nation; there can be no true legislator except the people. Whether looking back to the English Civil War or forward to future disputes between the Executive and Legislative branches, it makes clear the Legislative branch was dominant, with the Executive branch acting as its agent.

|

| Denis Diderot |

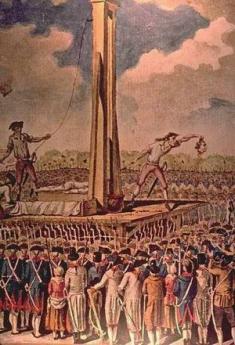

With this ringing warcry, the French model nevertheless ushered in the extremes of the Terror, the Guillotine, and the Napoleonic conquests. The consequences of the French constitution undermined world confidence in the benevolence of public opinion, at least deeply confounding those for whom the democratic rule was not totally discredited. Once more new life was breathed into allegiance for the monarchy, military rule, and dictatorship. Public opinion, it seemed, was not either invariably benign or comfortably far-seeing. The noble savage, mankind naked of tainted civilization, was not necessarily wise or worthy of trust. Edward Gibbons, the 1776 author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was pointing out where it all might lead if we completely believed in the collective goodness of the human condition. At the least, the failure of the French Revolution complimented the viewpoint of the Scottish philosopher, Adam Smith, who also in 1776 emphatically urged a switch in that reliance toward a sense of enlightened self-interest, as follows:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we can expect our dinner but from their regard to their own interest.

|

| Terror, the Guillotine, |

It is not surprising that Diderot rejected the Leibniz view of things that "All is for the best, in this best of all possible worlds." And, in view of his dependence on Catherine, not surprising he did not publish his rejection of it until 1823. Thomas Jefferson was in France as ambassador during the time of the American Constitutional Convention, fearing to confront George Washington; and likewise keeping his conflicting views private for several years. Eventually, they surfaced in the creation of an anti-Federalist political party along with the conflicts which kept the new nation in a turmoil for the following forty years. It is surely a testimony to the strength of the Constitution's design that the country was able to shift between such extreme governing philosophies but still hold together without changing the governing statement of purpose. Indeed, it is plausible to contend that our two political parties still continuously debate the useful tension between these two differing opinions.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Being a Small Country

|

| very pleasant |

LIVING in a small country seems to be very pleasant, and many people prefer it to the hustle, bustle and high taxes of living in a large country. Unfortunately, big neighbors are tempted to conquer and enslave you. Aside from this one disadvantage, many people would prefer a simple, quiet life among blood relatives, all tending to think the same way. It's one step above tribalism, and maybe it's a form of peaceful tribalism.

|

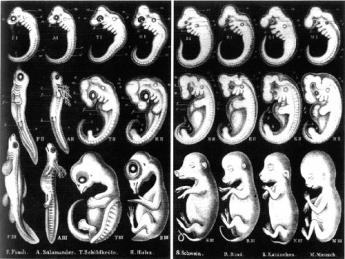

| Measles |

But our evolutionary ancestors didn't think they could afford this luxury. They lived in a strange wilderness filled with fierce aborigines who often took a notion to scalp you, even if you were willing to become a hunter-gatherer like them, because they scalped other hunter-gatherers, too. And they were good at making war. Later historians sometimes contend that European settlers only gained a foothold in the New World because the Indians had been weakened by smallpox, measles, and other contagions which advanced ahead of the exploring Europeans. English settlers along the Atlantic coast were able to overcome the Dutch and Swedes who preceded them, but the French in Quebec and the Spanish in Florida were a greater threat. Worst of all enemies were the rulers of England, who seemed to think it was natural to enjoy the benefits of the New World without the nuisance of living there. A century or more of conflict from the enemies who surrounded them had pretty well convinced the English Atlantic settlers that they simply had to get bigger and stronger. Otherwise, one of the many enemies surrounding them would eventually succeed in what seemed to be a universal goal: conquest.

|

| The summer of 1787 |

The colonists had learned one other thing. Their own loose federation of small peaceful states was in some ways worse than rule by an outside King. The Confederation had been constantly reluctant to surrender local power to a unified defense; almost by definition, an invader was better disciplined than the defenders of a loose tribal alliance. The defense alliance had few advantages for keeping local bickering under control and was definitely less effective with families and children to protect against a mobile force of adult male warriors. The Confederation barely held together during an eight-year war against a common enemy, and it was rapidly coming apart after peace was declared in 1783. The English and French could see all this, too. Once they settled their own war with each other, each of them planned to envelop the former colonies. So George Washington and James Madison gathered the Best and the Brightest together in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, intending to construct a practical plan for what almost all the colonists wanted: a Union. A Union strong and big enough so other nations would leave them alone. A Union was benign enough so its citizens would enjoy the same Liberty they had as a loose alliance. Divided informally into four interest groups, each of the four needed concessions to be made. But each also needed to leave the other three feelings they had gained something important as the price of surrendering to what some other group could not do without. Having found the vital concessions, it was then still necessary to tinker and re-balance, so that everyone could still "live with it". In essence: 1) The South had to be given time and forbearance to work out its difficult problem of slavery, moral qualms notwithstanding. 2) The nine small states had to be protected against perpetual domination by the three big ones, of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. 3) If America was to realize the full advantage of growing from thirteen states to fifty, existing old states must not take advantage of new ones. 4) Political revolution was not the end of it; there was also the Industrial Revolution. Fishing, lumbering, farming, trade, and cotton, would in some way need to accommodate banking and manufacturing, assisting rather than upsetting other compromises. Given these tangled issues, it would be a long, hot summer in Philadelphia.

|

| Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 |

Three of the four main problems were obvious, demanding to be addressed. Slavery was obvious from the start; you either solved this problem or the South would walk out. The western wilderness was bigger than existing America; it too could not be ignored. And finally, huge variations of climate and resources led to local specialization; a marvelous thing, if you could trust your suppliers and customers to cooperate. But curiously, none of these issues got directly to the political problem the Constitutional Convention was meant to solve, which was unifying thirteen different sovereignties, each of which was prepared to get up and walk out. The modern nation state was created by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648; its guiding principle was mutual respect for local sovereignty. Having pacified over a hundred contentious central European states, it required a great deal of self-assurance for anyone to flout it. It seemed hard to imagine any way to remain sovereign, without commanding a vote equal to that of other sovereignties. The delegates from the State of Delaware, which had separated from Pennsylvania within the past decade, were "prohibited [by their legislature] from changing the Article in Confederation establishing an equality of votes among the States". Just what agitated the minds of the Legislature of Rhode Island was kept private, but something about a Union bothered them so much they refused to send delegates to Philadelphia even to discuss Union. After they assembled and started having dinner together at taverns, and later as they were beginning to vote in coalitions, one thing began to emerge. The small states banded together, hung out together, talked alike, and began to vote alike. Their emerging leader was John Dickinson of Delaware, the author of the Articles of Confederation, and very likely one of the prime agitators in the lower three counties of Pennsylvania -- breaking off from Pennsylvania and becoming the State of Delaware. Furthermore, Dickinson had been Governor of both Delaware and Pennsylvania, so he was very familiar with the deplorable behavior of the Legislature of Pennsylvania, now and for decades in the past. It took a long time for this sly old political operator to show his cards, but when he did, he gave James Madison the shock of his life. Madison, the near neighbor of George Washington and leader of the Virginia delegation, the author of the Virginia Plan, and the clear authority on the politics of government in America was busily consumed with working out the details of the emerging Constitution. Obviously, it went to his head a little, and so he was dumbfounded when Dickinson drew him aside in the corridor to tell him he wasn't going to have a Constitution at all. Dickinson was walking around with the votes in his pocket of five or six of the nine small states and was telling Madison that the small states were fed up, and not going along. Young Madison was suddenly confronted by the most respected lawyer in America, whose timing was perfect. For what may have been the first time in his life, Dickinson fully revealed the depth of his annoyance, that the big states would always take the little ones for granted. That the little ones were always expected to be deferential to the big fellows in charge of the big states. And then the clincher: "I would rather risk conquest from a foreign state than being forever dominated by my larger neighbors." That put it in a nutshell. If the only reason for joining a Union was to be protected from foreigners, Dickinson wasn't so sure he preferred his coalition partners. Evidently, this was the feeling of most of the other small states at the Convention, and it may well be the feeling of all small states, anywhere and everywhere.

|

| Promoting the Abolition of Slavery |

Once the Convention got the idea, solving it became comparatively easy, but why waste an opportunity? There is a good reason to suppose it was Ben Franklin, silent as a cat watching a mouse, who matched it up with slavery. His fellow Pennsylvania delegate, James Wilson, had prepared the way by starting the discussion of granting 3/5 representation for slaves, but it had received comparatively little notice in the previous few weeks. Franklin rammed it home, adding a sop to the large states by according to the House of Representative sole power to introduce money legislation. Two of the main issues of the convention were solved with one agreement, small-state representation, and slavery. Who can say how long he had been nursing this idea. He had agreed to be president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, about a month before the Constitutional Convention began. Prior to that, he and his wife had owned a slave or two, for many years. On June 2, the society adopted a resolution to end the slave trade and presented it to Dr. Franklin, asking him to present it to the Convention. He never did, explaining later it was "advisable" to let the matter lie over. In August, Alexander Hamilton blocked a similar resolution from the New York Manumission Society, even though he had been a fervent lifelong opponent of slavery.

Political Parties, Absent and Unmentionable

|

| King George III |

BECAUSE America had recently revolted to rid itself of King George III, the Constitutional framers of 1787 sought to construct a government forever free from one-man rule. Inefficiency could be accepted but central dictatorial power, never. It is unrealistic however to expect a wind-up toy to keep working forever, and our Constitution creates the same worry. After two centuries, some chinks have appeared.

|

| Founding Fathers |

Political parties existed in 18th Century England and Europe, but the American founding fathers seem not to have worried about them much. Within ten years of Constitutional ratification, however, Thomas Jefferson had created a really partisan party which naturally provoked the creation of its partisan opposite. James Madison was slowly won over to the idea this was inevitable, but George Washington never budged. Although they were once firm friends, when Madison's partisan position became clear to him, Washington essentially never spoke to him again. Andrew Jackson, with the guidance of Martin van Buren, carried the partisan idea much further toward its modern characteristics, but it was the two Roosevelts who most fully tested the U.S. Supreme Court's tolerance for concentrating new powers in the Presidency, and Obama who recognized that the quickest way to strengthen the Presidency was to weaken the Legislative branch.

Dramatic episodes of this history are not central to present concerns, which focuses more on the largely unnoticed accumulations of small changes which bring us to our present position. Wars and economic crises induced several presidents, nearly as many Republicans as Democrats, to encourage migrations of power advantage which never quite returned to baseline after each crisis. Primary among these migrations was the erosion of the original assumption of perfect equality among individual members of Congress. A new member of Congress today may tell his constituents he will represent them ably, but when he arrives for work he is figuratively given an office in the basement and allowed to sit on empty packing cases. This is not accidental; the slights are intentional warnings from the true masters of power to bumptious new egotists, they will get nothing in their new environment unless they earn it. Not a bad idea? This schoolyard bullying is a very bad idea. If your elected representative is less powerful, you are less powerful.

|

| Houses of Congress |