3 Volumes

Constitutional Era

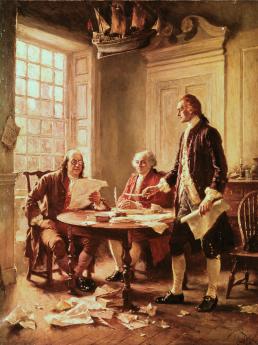

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

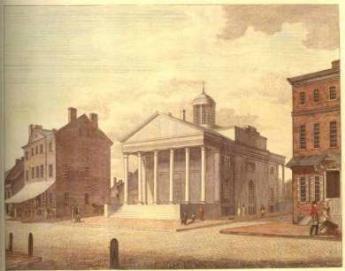

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

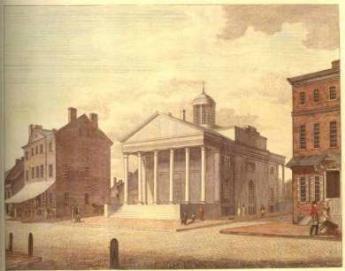

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

British Abandon Philadelphia, Morris Takes It Back

It was fear of the French Fleet that made the British abandon conquered Philadelphia. Robert Morris took over and restored the insurgent headquarters, a hundred miles from the Ocean.

Fort Wilson: Philadelphia 1779

|

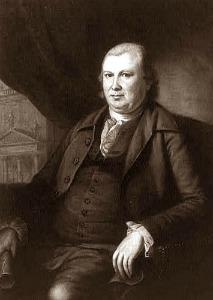

| James Wilson |

OCTOBER 4, 1779. The British had conquered then abandoned Philadelphia; an order was still only partially restored. Joseph Reed was President of the Continental Congress, inflation ("Not worth a Continental") was rampant, and food shortages were at near-famine levels because of self-defeating price controls. In a world turned upside down, Charles Willson Peale the painter was a leader of a radical group of admirers of Rousseau the French anarchist, called the Constitutionalist Party, leaning in the bloody direction actually followed by the French Revolution in 1789. Peale was quick to admit he had no clue what to do with his leadership position and soon resigned it in favor of painting portraits of the wealthy. Others had deserted the occupied city, and many had not yet returned. The Quakers of the city hunkered down, more or less adhering to earlier instruction from the London Yearly Meeting to stay away from any politics involving war taxes. About two hundred militia roamed the city streets making trouble for anyone they could plausibly blame for the breakdown of civil order. Philadelphia was as close to anarchy as it would ever become; the focus of anger was against the pacifist Quakers, the rich merchants, and James Wilson the lawyer.

|

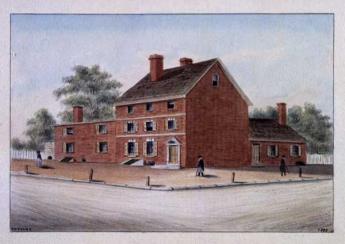

| Fort Wilson |

Wilson had enraged the radicals by defending Tories in court, much as John Adams got in trouble for defending British troops involved in the Boston Massacre; Ben Franklin advised Wilson to leave town. It is still possible to walk the full extent of the battle of Fort Wilson in a few minutes, and the tourist bureau has marked it out. Begin with the Quaker Meeting at Fourth and Arch. A few wandering militiamen caught Jonathan Drinker, Thomas Story, Buckridge Sims, and Matthew Johns emerging from the Quaker church, and rounded them up as prisoners. The Quakers were marched down the street for uncertain purposes when the militia encountered a group of prominent merchants emerging from the City Tavern. Unlike the meek Quakers, Robert Morris and John Cadwalader the leader of the City Troop ordered the militia to release the prisoners, behave themselves, and disperse; Timothy Matlack shouted orders. It was exactly the wrong stance to take, and about thirty prominent citizens were soon driven to retreat to the large brick house of James Wilson, at the corner of Third and Walnut, known forever afterward as Fort Wilson. Doors were barred, windows manned, and Fort Wilson was soon surrounded by an armed, shouting, mob. Lieutenant Robert Campbell leaned out a third story window and was soon dropped dead by a lucky bullet. It remains in dispute whether or not he fired first. Crowbars were sought, the back door forced open, but the angry attackers scattered after fusillades from inside.

|

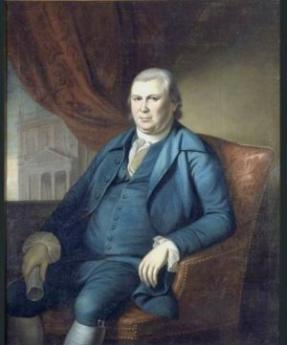

| Joseph Reed |

Down the street came President Reed on horseback, ordering the militia to disperse, with Timothy Matlack at his side; both men were well-known radicals, here switching sides to maintain law and order. The City Troop arrived, an order was given the cavalry to Assault Every Armed Man. The radicals were finally dispersed by this makeshift cavalry charge, cutting and slashing its way through the dazed militia. When it was over, five defenders were dead and about twenty wounded. Among the militia, the casualties were heavier but inaccurately reported. Robert Morris took James Wilson in hand and retreated to his mansion at Lemon Hill; Wilson was the founder of America's first law school. Among other defenders huddled in Fort Wilson were some of the future framers of the Constitution from Pennsylvania: General Thomas Mifflin, Wilson, Morris, George Clymer. Equally important was the deep impression left on radical leaders like Reed and Matlack, and Henry Laurens, who could see how close the whole war effort was to dissolution, for lack of firm control. Inflation continued but the center-productive price control system was abandoned and never revived; the Patriots had a bad scare, and the heedless radicals forced to confront the potentially disastrous consequences of their own amateur performance when entrusted with the power and responsibility they had just been demanding. It was one of those rare moments in a nation's history when the way suddenly opens to previously unthinkable actions.

|

| Timothy Matlack |

The Battle of Fort Wilson was the only Revolutionary War battle fought within Philadelphia city limits; a revolution within a revolution, every participant was a Rebel patriot. Reed and Matlack were the two most visibly appalled by the whole uproar, forced by circumstances to attack the forces of their own political persuasion. But it seems very certain that Robert Morris and the other prosperous idealists were also left with an indelible conviction that even a confederation must maintain central command and discipline with an iron will, or all might be lost. A knowledgable French observer estimated that Robert Morris then owned assets worth eight million dollars, an almost unimaginable sum for the time. But he would lose every penny if effective political control could not be restored. A few days later in the October election, he and all the other Republican (conservative) officials lost their seats. It did not matter; Morris then knew what to do, and his opposition didn't.

Peggy Shippen and Benedict Arnold: Fallen Idols

|

| General Burgoyne |

After defeating Washington's troops at the battle of Germantown, the British then occupied Philadelphia for the better part of a year. The town was a mess, with food shortages typical of the squalor of any occupying army equalling the existing population. Washington was forced to fall back to the natural fortress of Valley Forge. The city of Philadelphia was not exactly under siege, but it was as difficult a place for British troops to live as a besieged city. For his part, Washington was forced to shiver and starve in the nearby mountain valley, at least consoled by distant news of American achievements. General Burgoyne and his army were soon captured at Saratoga by General Gates under humiliating circumstances. Clearly, the dashing hero of this event had been Benedict Arnold on a white horse leading the charge, getting wounded in the leg in the process.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in Paris |

Benjamin Franklin in Paris trumpeted the news of this victory, reminding the French of Washington's earlier victory at Trenton, and maneuvering it all into a treaty of alliance. With the French fleet in the nearby Caribbean, Philadelphia was no longer a safe place for the British to stay a hundred miles upriver, and the idea of abandoning occupied Philadelphia began to grow. Having gambled on British victory in defiance of London's orders, the Howe brothers were not in a position to argue with new orders. The British soldiers inside the city were more comfortably housed than the American troops outside it, but nobody was exactly comfortable. The American Congress had, of course, fled to the hinterlands. All in all, it suddenly became uncertain who was going to win this war.

|

| Peggy Shippen |

The American population at this time has been described as a one-third rebel, one-third Tory, and one-third trying to hunker down to see who would win. Many of the seriously committed Tories had fled from Philadelphia when the rebels took charge, while pacifist Quakers were a little hard to classify. Generally speaking, the prosperous merchant class had never been persuaded King George was all that bad, while the less prosperous artisans were the fervent patriots. Under such conditions, many people who privately leaned in either direction found it was best to seem non-committal. The British were billeted in private homes; the Officers in the best houses of the merchant class, the common soldiers generally housed in the homes of the artisans. Although the soldiers and the artisans did not mix very well, circumstances permitted the aristocratic officers getting on pretty well with the merchants whose houses they occupied. The girls in the colonial families seemed immediately attractive to the British officers, who were far from home, while the officers also seemed pretty glamorous to the girls. So, it is not exactly surprising that the most beautiful colonial belles like Peggy Shippen and Peggy Chew found themselves frequently in company with dashing officers like Major John Andre. Andre would likely have been a heartthrob in any circumstance since he had risen to the rank of adjutant-general at a young age, wrote poetry and plays, reputedly was rich, and was regularly the life of any party. Nor is it surprising that generations of Peggy's descendants have treasured a lock of his hair.

|

| Margaret Oswald Chew Howard |

When the decision was finally made to abandon Philadelphia, six of the British officers personally contributed twenty-five thousand dollars to throwing Philadelphia's most famous, most splendiferous party, called The Machianza. It went on for days, had real jousting matches between officers dressed like knights in armor, banquets and all that sort of thing. It was Andre's idea, and he was enthusiastically in charge. Surviving records of the event do not show that Peggy Shippen was present, but in view of what happened later, much of her correspondence has been destroyed. It's pretty hard to imagine she wasn't there.

|

| Major General Benedict Arnold |

The British then marched away, and Washington's troops cautiously followed, assuming control of the city. Major General Benedict Arnold had been sent from Saratoga to Valley Forge to recover from his leg wound, and probably also to raise morale among the troops celebrating the now-famous hero. Washington more or less immediately decided to pursue the British across New Jersey, thus leading to the battle of Monmouth as the two armies raced for the Naval vessels in lower New York harbor. Since General Arnold had not fully recovered from his wounds, he was installed as the military governor of a somewhat bedraggled Philadelphia. Naturally, he was the center of the social scene, and soon was pursuing Peggy Shippen in every way he knew, which included some pretty gloppy letters in Romantic style. Peggy's father was uneasy about his intentions but was eventually mollified by Arnold's purchase of the house called Mount Pleasant, now a tourist attraction in Fairmount Park. With this evidence that his prospective son in law was at least likely to stay in Philadelphia, Edward Shippen finally repented of his opposition to the marriage of his daughter. But the new couple were soon off to West Point, where Arnold had kept up a persuasion campaign with George Washington, to get himself appointed the commandant of the main northern defense of the Hudson River. A point for Philadelphian tour guides to remember is that Peggy and Benedict never got a chance to live in Mount Pleasant.

Arnold originally lived in New Haven, Connecticut, where he had established quite a sea-faring reputation as a merchant, some would say privateer, others would say buccaneer. There is no doubt he was aggressive, and combative, and considered himself a little bit above the law. These qualities made him outstanding at Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga, and are always more highly valued in young men in a war. Unfortunately, he made a bitter enemy of Joseph Read who was briefly his neighbor, and later was President of the Continental Congress. Read accused Arnold of smuggling and trading with the enemy, and was so determined about it that Arnold was scheduled for court-martial, but postponed. Arnold was loudly defensive about the whole matter, and public sympathy was on his side. In view of what soon happened, he might well have been cleared by the court, but likely there was some truth to the accusations. Using Peggy as a go-between, he entered into a correspondence with Andre (then the adjutant-general in New York) offering to deliver the surrender of West Point, three thousand prisoners, and possibly George Washington himself in return for what might today be half a million dollars. As a note of realism, he was willing to accept half that in the event of failure. The British were particularly anxious to acquire American prisoners to exchange for their own troops captured at Saratoga. Unless Arnold was a total sociopath, he must have thought he had quite a grievance.

|

| Lord Cornwallis |

Things went along surprisingly well at first, with negotiations for price back and forth, plans for attacking West Point moving along with the Navy, and Andre disguising himself for a visit to Arnold in his house to the south of the Fort on West Point. Much of the success was due to the movie-star reputation of Benedict Arnold; few could imagine such a hero doing such an unheard-of thing. However, the plot was discovered while Washington was away visiting the Fort, and Arnold hastily abandoned his family and fled to a waiting British warship. Andre decided to make his way south to the ship through rebel territory, but local soldiers and farmers were much more suspicious than others had been, and after penetrating his disguise, found incriminating papers concealed in his boots. Since he was out of uniform behind enemy lines, Andre was by definition a spy, which required hanging. He made a plea to be shot like a gentleman, but Washington with tears allegedly in his eyes refused. With much bravado, Andre jumped atop his own casket and placed the noose around his own neck, a behavior much admired by his compatriots when they heard of it

Meanwhile, Peggy had put on a crazy-woman act which apparently convinced Washington to be lenient, and allow her to rejoin her husband. The couple stayed in New York for a few months, toying with commands of loyalist troops in the south, but eventually taking ship for England. Lord Cornwallis was on the same ship and they became pals as shipmates, pleasing Arnold quite a lot. Unfortunately, British society was only stiffly polite to them, and many did not trouble to conceal their disdain for traitors to any cause, and thus life in England was not smooth. By that time, it is possible that many had begun to suspect the whole idea of treason was Peggy's idea from the start, as is today the conventional view of it. As an American aristocrat, she was uncomfortable with the rebels in Philadelphia, and as the impetuous wife of an accused smuggler, it was difficult to fit in with either the Quakers or the merchants with loyalist leanings. No doubt she heard some catty whisperings among her friends and relatives about her other romantic associations. The British paid them their promised pensions, but a career in the British Army was out of the question for her husband. But the real shock would come, from discovering the British as a whole didn't much care for their behavior, either.

Robert Morris, Financial Virtuoso

For reader convenience, we here divide Robert Morris' financial rescue of wartime America into two parts before and after 1780, because he had two episodes of being officially in charge. The first immediately followed the Battle of Fort Wilson when chaos and worthless paper money required a strong hand; it will be described next. The second episode followed the later near-revolt of the Continental Army but has already been outlined. Here, Morris was recalled to the office with chaos erupting at the end of the war came in sight and everyone was reluctant to fight battles for no military purpose. At the same time British, French and American politicians connived for victory in a war each had failed to win militarily. For simplicity, time sequences have been distorted a bit, concentrating the creation of modern banking into the second episode, where failure to coordinate banking with taxation ultimately led to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Chronology has been sacrificed to enhance clarity. It is now time to return to the brilliant expedients Morris employed after he took charge following the Fort Wilson shocker, omitting some of the banking details already described.

What helped the first crisis most was the ready availability of a financial genius to turn around a crisis, when just about everyone else was at a total loss. Robert Morris had made his fortune, probably the richest man on the continent, and nursed the grievance of crowd abuse at the Battle of Fort Wilson. He had some novel concepts to test; it is not too much to say he showed them off, particularly since they displayed a man in charge with prodigious energy, applying a financial virtuosity of seemingly unlimited ideas. No one else came close to Morris in stature, and he must be forgiven for flaunting it a little.

|

| Robert Morris |

At the climactic moment, however, Morris played coy. He was not so sure he would accept the office of Financier, a term newly invented for the occasion. Accepting Ben Franklin's cynical assessment of the future, he wanted everyone to be clear: he was not going to give up his private partnerships. And he insisted on his right to hire and fire anyone at all within the government bureaucracy who was concerned with public money. He accepted responsibility for new debts of the government, but not for old debts incurred before he took office. He would furthermore delay taking the oath of office for a few months. These conditions naturally generated wild opposition in Congress; Morris was serene, and Congress finally had to agree. Most of these terms had some obvious purpose while making no secret of his distrust of Congressmen. In fact, the opposition might well have hardened its position if the purpose of delaying the oath had been fully expressed. Morris wanted to delay becoming a federal officer in order to delay resigning from the Pennsylvania Assembly. During the interval, he applied similar power tactics to the Legislature, ending up simultaneously in charge of both state finances and federal.

|

| Yorktown: Oct. 19, 1781 |

That purpose was soon to emerge, as just one instance of many tough tactics. Inflation tossed and turned the finances of everyone, so Morris would buy with one currency and sell with another, taking advantage of brief fluctuations, then quickly reverse the currency transaction when advantages shifted. He arranged with the French and Spanish ministers to keep their loans and foreign aid in separate accounts, applied the same techniques with state accounts, and even between near and distant counties within Pennsylvania. He thus had a choice between many currency values at any one moment. His far-flung commercial network supplied him with more precise information than his counterparties could get, and usually more quickly, so his trading activities were usually profitable. One rather extreme example was the arrangement with Benjamin Franklin in Paris; Morris would write checks to Franklin in one currency and Franklin would write identical deposits back to him on the same day but a different currency. He thus extended ancient practices among international merchants, carrying them over to government operations, which had the effect of creating a modern currency exchange. To outsiders, however, particularly his political enemies in Massachusetts and Virginia, it looked fishy. To modern observers, the astonishing thing was his ability to keep such complexity in his head. The political class which even today sees it as natural that governments might want to manipulate currency as they please might describe Morris strategies as dubious. Those who believe the market price is usually the true price however, must applaud this strategy for forcing manipulated prices back to market levels. Since here has rested the central dispute in American politics for two centuries, Morris must be credited with inventing even that dispute. One would normally suppose that doubling the silver price of American currency in two months would vindicate his trading strategy; but it has not always done so, suggesting the nature of the questioning has been more ideological than economic.

Within days of assuming office, the "legal tender" laws were repealed, stripping government of the ability to force its citizens to accept the worthless currency, impose rationing and price controls, and otherwise assume the mantel of "sovereignty". Like a miracle, food began to reappear in the Philadelphia marketplace at a lower price, and confidence in the competence of government began to return. To whatever degree the British ministry had been deliberately stalling the peace talks in the hope of American collapse, this incentive was dissipated.

The list of financial innovations which Morris produced in a remarkably short time, is seemingly endless. He next became central in the creation of the first American bank of the modern sort, the Bank of North America. And somewhere in that welter of activity appears to be the recognition of the so-called yield curve. Loans for a few weeks or months command a much lower interest rate than long-term loans; in the colonial period, almost all loans were for six months or less. Morris seems to have realized early that great profitability could be achieved by merging a sequence of several short loans into one long one. He thus devised a number of strategies which had the general effect of linking short loans together. Using the remittance for a transatlantic cargo in one direction as payment for the return cargo on the same ship was an early example. Once you grasped the idea and did it deliberately, long sequences of linked loans began to suggest themselves. Just to complete the thought, it might be noticed that present-day globalization reverses the process, with shorter-term loans for components substituting for longer-term loans for the entire assembled product. With lower interest rates, competitive prices can be reduced, unless a choice is made to increase profits.

There's one last issue in Robert Morris folklore: Did he finance the whole Revolution out of his own pocket? The answer is surely no because Beaumarchais ended up spending much more than any other individual, however involuntarily. The degree to which hard currency originated with the French, Spanish and American governments is a little unclear, and war damages are impossible to appraise. There were moments when Morris did personally finance major cash shortages, adding the considerable advantage of speeding up what could be a cumbersome process of budgeting, committee consideration, disputes, and hesitation. Where it was feasible, he sought restitution. Every bureaucrat has experienced delays and obstructions he dreams of eliminating by simply paying for it himself; Morris had the advantage that within reason, he could afford it.

As a very rich man, his more important personal contribution was his pledge to make good if the Treasury defaulted. Creditors generally preferred his credit to that of the government; his pledge was to pay if the government could not. His "Morris Notes" were not paying, but rather reinsuring government debts, in modern terms offering a Credit Default Swap. If we lost the war and our debts defaulted, Morris would have lost everything he had. But short of that, his pledge would result in much smaller losses. The public couldn't be expected to understand all that, so some simplified explanations were understandable. There were probably a number of similar examples, but near the end of the war, there was a particularly clear one. The Continental Army was very close to revolt when it looked as though Congress would disband the soldiers without paying them; there was no money but unpaid demobilization would likely send rioting soldiers through the countryside. Morris came forward with a million dollars of his own money and saved the day. Washington was forced to make emotional speeches appealing to the patriotism of the troops, but with most of the army barefoot, that was not certain to hold them back. Under those circumstances, to come forward later like Arthur Lee and remind everyone that Morris had once refused to sign the Declaration of Independence, was ingratitude of the meanest sort.

The accusation made after the war was that he profited from government losses, but there has never been evidence of that. His position was that he came out about even. Unspoken in these quarrels was the plain fact that until he got involved in the post-war real estate boom, he didn't need to cheat. Probably didn't even have time for it.

The Revolutionary War continued for two years after Morris took office for the second time, so war losses continued in spite of improved financial management. Both the French Government and the American one were at the edge of bankruptcy. Britain was also in political chaos, but it was only small consolation that Parliament had granted Independence to the Colonies when King George III remained adamant that it wasn't going to happen to his colonies. Strengthened by the British defeat of the French Caribbean fleet, the capitulation by the Spanish about Gibraltar, and great uncertainty about the Crimea and India -- almost anything was possible. Eventually, matters began deteriorating again. The British even then had the financial strength to hold out much longer, but obvious neglect of other opportunities eventually wore them down. Morris seemed to be winning, just by not losing.

In the midst of such anarchy, Morris had to admit his greatest failure as the Financier but was already formulating his plan for setting things on their feet. The Revolutionary War as seen by a financier had either been won by the British system of taxation or else lost by the American and French lack of such a system. It was irrelevant whether the War was described as a defeat for Britain or a victory for America; in Morris' view, the British had a good system and we had a poor one. No nation can finance a major war out of current receipts; you have to borrow. Your security for loans is the economy of your nation. Even if your illiquid assets are adequate for the war, the banking markets regard your ability to pay cash for the interest on the loan as their only reliable test of your solvency. That is, a nation at war must have the ability to keep the bankers happy with regular interest payments. For that, a nation had to have a proven system of reliable taxation. Britain had it, and the American/French alliance didn't. Franklin's masterful diplomacy was just lucky enough to achieve generous terms, but that wasn't good enough, we had to have a Federal tax system to survive and thrive. And to achieve that, we had to have a new Constitution. Never mind that resentment about British taxes got us into this mess. Never mind the chaos attending the Treaty of Paris. Never mind the war-weariness, bitterness, and destitution of the troops. Never mind that Morris was now about to embark on one of the most mind-boggling real estate ventures in history, was going to go to debtor's prison, was going to engage in millions and millions of dollars of borrowing and restitution. Never mind. We needed a new Constitution, and we were going to get it. Think big.

Morris Defends Banks From the Bank-Haters

|

| Robert Morris |

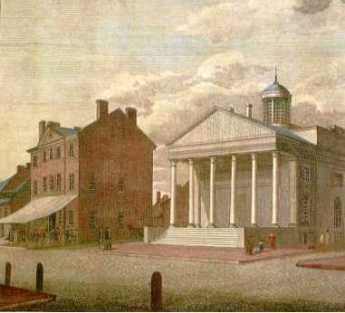

IN 1783 the Revolution was over, in 1787 the Constitution was written, but the new nation would not launch its new system of government until 1790. It was a fragile time and a chaotic one. Earlier, just after the British abandoned their wartime occupation of Philadelphia in 1778, Robert Morris had been given emergency economic powers in the national government, whereas the state legislatures were struggling to create their own models of governance, often in overlapping areas. While the Pennsylvania Legislature was still occupying the Pennsylvania State House (now called Independence Hall) in 1778, it -- the state legislature -- issued the charter for America's first true bank the Bank of North America, and in 1784 the charter came up for its first post-war renewal. Morris was a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly both times. Although he was not a notable orator, it was said of him that he seldom lost an argument he seriously wanted to win. Keeping that up for several years in a small closed room will, unfortunately, make you many enemies.

|

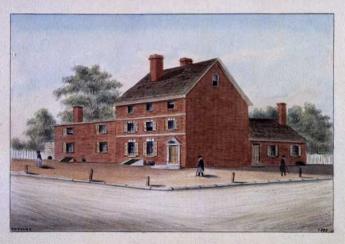

| Tavern and Bank |

Morris was deeply invested in the bank, in many senses. He had watched with dismay as the Legislature squandered and mismanaged the meager funds of the rebellion, issuing promissory notes with abandon and no clear sense of how to repay them, or how to match revenues with expenditures. There was rioting in the streets of Philadelphia, very nearly extinguishing the lives of Morris and other leaders, just a block from City Tavern. Inflation immediately followed, resulting in high prices and shortages as the farmers refused to accept the flimsy currency under terms of price controls. Every possible rule of careful management was ignored and promptly matched with a vivid example of what results to expect next. Acting only on his gut instincts, Robert Morris stepped forward and offered to create a private currency, backed by his personal guarantee that the Morris notes would be paid. The crisis abated somewhat, giving Morris time to devise The Pennsylvania Bank, and then after some revision the first modern bank, the Bank of North America. The BNA sold stock to some wealthy backers of which Marris himself was the largest investor, to act as last-resort capital. It then started taking deposits, making loans, and acting as a modern bank. Without making much of a point of it at the time, the Bank interjected a vital change in the rules. Instead of Congress issuing the loans and setting the interest rates as it pleased, a commercial bank of this sort confines its loans to a fraction or multiple of its deposits, and its interest rates are then set by the public through the operation of supply and demand. The difference between what the Legislatures had been doing and what a commercial bank does, lies in who sets the interest rates and who limits the loans. The Legislature had been acting as if it had the divine right of Kings; the new system treated the government like any other borrower. As it turned out, the government didn't like the new system and has never liked it since then. Today, the present system has evolved a complicated apparatus at its top called the Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve, most of whose members are politically appointed. Several members of the House Banking Committee are even now quite vocal in their C-span denunciations of the seven members of the Open Market Committee who in rotation are elected by the commercial banks of their regions. Close your eyes and the scene becomes the same; agents of the government feel they have a right to control the rules for government borrowing, while agents of the marketplace remain certain governments will always cheat if you don't stop them. This situation has not changed in two hundred years and essentially explains why some people hate banks.

|

| Seigniorage |

That's the real essence of Morris's new idea of a bank; other advantages appeared as it operated. The law of large numbers smooths out the volatility of deposits and permits long-term loans based on short term deposits. Long-term deposits command higher loan prices than short-term ones can; higher profits result for the bank. And a highly counter-intuitive fact emerges, that making a loan effectively creates money; both the depositor and the borrower consider they own it at the same time. And finally, there is what is called seigniorage. Paper money (gold and silver "certificates") deteriorates and gets lost; the gold or silver backing it remains safe in the bank's vault, where it can be used a second time, or even many times.

For four days, Morris stood as a witness, hammering these truisms on the witless Western Pennsylvania legislators. At the end of it, scarcely one of them changed his vote, and the bank's charter was lost. But at the next election, the Federalists were swept back into the majority, defeating the opponents of the bank. Although, as we learn the way democracy works, still leaving them unconvinced of what they do not want to believe.

Private Sector Disciplines Congress

|

| Adam Smith |

Two centuries after our present narrative, when President William Clinton once proposed a financial adventure, Robert Rubin replied, "The bond market won't let you do it." In this way, the former Wall Street investment banker educated his politician boss that the most powerful wealth of any nation is hidden, locked up in homes, businesses, infrastructure, population education, and other long-term assets. Such wealth normally transforms into cash only when the Treasury borrows it (usually by selling government bonds) because by Constitutional intention the alternative of raising taxes is essentially confiscatory. By contrast, the use of bonds requires only an agreement on price. Bond use is thereby related to supply and demand, with the government generally selling bonds and the public generally buying them. The government sells as many bonds as it pleases, but the price received will immediately sink if too many bonds are for sale. Viewed another way, bond prices announce the market's daily assessment of probable government solvency because the isolated bond market is solely interested in the probability of being repaid.

In modern wars, the longest purse must generally determine the event.

|

| George Washington, May, 1780 |

In 1779 there was no bond market, so Robert Morris set about creating one. Acting then as only a private citizen, but faced with his government being run into the ground, Robert Morris proposed the creation of a "bank", the Bank of Pennsylvania, created, owned and managed by private citizens. The first bank in the nation didn't take retail deposits and was unlike banks we have today in other ways. Modeled more like a bond fund of the Twenty-first century, the Bank of Pennsylvania got its funds through fairly large subscriptions from wealthy people. Robert Morris himself was probably the heaviest subscriber. A bond market was thus created, with subscriptions flooding in when the public was pleased with its government, and flooding out when the public didn't like the looks of things. Naturally, there was a profit: the bonds the bank sold to subscribers were priced higher than the bonds the bank bought from the government. In this way, the public was assured the process of setting prices remained in neutral hands. The government could print bonds freely, but the Bank of Pennsylvania couldn't buy them unless somebody gave it some money, and that wouldn't happen unless prices rose to the "market clearing level," of agreement between potential buyers and sellers. The nature of the deal didn't change much when later banks got their funds from deposits, and one later enduring feature also didn't change: Governments hate banks because banks are in a position to frustrate governments intent on spending what they please.

|

| Jacques Necker |

Quite soon, the public could be visualized as composed of debtors and creditors; the two main political parties have mostly had a matching composition. Progressive politicians, like Albert Gallatin, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Robert LaFollette, William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson, and Barack Obama have demonized banks, often threatening to nationalize or eliminate what is basically a neutral bookkeeping function. Adam Smith had written The Wealth of Nations three years earlier; Morris gave copies to friends and had obviously read the book, as had Alexander Hamilton. Morris also entered into exciting correspondence with Jacques Necker, the Swiss/ French banking genius, but Necker soon died, leaving it uncertain how much influence he had on America. This group of people gave us a system in which the public markets set the price of a currency, not the other way around. In the 1779 case, galloping inflation quickly came under control and goods soon reappeared in the markets, although the continuing war exerted relentless pressure until 1783 for the government to do more borrowing.

|

||

In another irony, during the year he was totally out of office (conservatives were restored to power in the October 1780 election), Morris enjoyed his greatest personal prosperity and exerted almost total personal control of the currency; it was fruitless to accuse him of using government office for private gain when he held no office. During this brief interval, Morris also created the first American corporate conglomerate, the series of partnerships called Peter Whitesides and Company. At least as profitable were his personal relationships with the French Ambassador Luzerne and the emissary from Havana, Juan de Miralles, who introduced him to large pools of investment capital from abroad. His American businesses became almost too numerous to count, again highlighting his prodigious ability to work. Meanwhile, his social life was as active as anyone's, extending his hospitality and affability world-wide, and anticipating a return to public life. All of this took about a year.

During this period, his sole civic activity was the Bank of Pennsylvania. As a bank, it had a relatively short life. As a subtlety of government, it would be hard to find its equal in any other empowerment of the people. Many centuries of history had formerly taught the lesson that public office was the way to get seriously rich. Morris flaunted a brand new American banner: public corruption was a waste of time, like any other zero-sum game.

Robert Morris Invents American Banking

The finances of our new nation were subject to many violent swings from the day the British abandoned Philadelphia in 1778 right up to the end of the war in 1783, but things steadily turned for the better after Robert Morris took charge of the Department of Finance in 1780, and particularly a year later when he was given the confusing title of Financier. Those two-mile stones could be marked in another way; with the establishment of the Bank of Pennsylvania in 1780, and then a year later the Bank of North America. Both institutions were products of the Morris imagination, matching the evolving state of his thinking. But the politicians only permitted these innovations after bitter battles, so in a sense, they matched what he could accomplish politically, in two steps grudgingly forced on him by the world's reluctance to trust his ideas. It remains unclear which innovations originated with Robert Morris, and which ones were derived from the Swiss economist Jacques Necker, who had become the French Minister of Finance, or Adam Smith whose Wealth of Nations was published in 1776. There were obvious similarities in the approach of these men, and a means of communicating existed through Silas Deane in Paris. Curiously, Necker was primarily famous in Europe for shrinking the bloated and corrupt bureaucracy of French financial administration. It is not irrelevant that whenever clear thinking replaces floundering, waste and abuse begin to subside.

|

| The First Pennsylvania Bank |

The Pennsylvania Bank of 1780, unrecognizable today as a "bank", resembled a modern bond fund, operated as a partnership. It initially raised 300,000 pounds mainly from wealthy merchants, in return for interest-bearing 6-month notes. That money was promptly used to buy 500 barrels of flour for the troops at Morristown NJ. The bank thus served to transfer private funds to public purposes, which was what a rich nation urgently needs when its troops are starving.

It is always difficult to propose new ideas; in this case Morris also had to overcome resistance to taxes, which many citizens thought the Revolutionary war was all about. Taxation is, undeniably, a form of confiscation. When danger is clear at moments of panic, voluntary contributions may suffice; it is then almost sufficient to pass the hat. Soon enough, however, the government needs to increase incentives to induce the public to take the risk, hence interest rates offered by the bank must become market-driven, responding to negotiated public opinion. In short catastrophic wars for survival, a nation can gambles all its resources heedlessly. But steadily financing an eight-year war ultimately becomes a constant search for acceptable ways to transfer enough private wealth to cover the military effort, but not enough to stir up inflation. Floating interest rates, ultimately based on prevailing public opinion, do offer a match with changing prospects for victory or defeat, but only when they are not tampered with. Mismatches between public opinion and interest rates might seem tempting short-cuts to government, but they lead to inflation, price controls, rationing, and shortages of goods.

There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain of success, that to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.

|

| Niccolo Machiavelli --The Prince |

In the United States in 1780, a huge disparity between the sudden wealth of privateers, and the abject poverty of Washington's army provoked trouble. At a time when the army was barefoot, Robert Morris' personal wealth was estimated at eight million dollars, but it seems likely the contrast between barefoot soldiers and free-spending privateer sailors was even more divisive since recruitment preferences were affected. The government tried many things: inflation default, devaluation default, confiscations, and even a few timid taxes. That duty was even proposed in Congress to be levied on the prize captures of privateers, suggests the public was alert to windfall profits. But it seemed oblivious to the principle that if you tax something, you get less of it; Congress was effectively proposing to punish the capture of British ships.

The idea of some sort of bank first came to Robert Morris less than a week after he stepped forward into the rioting streets to offer ten thousand pounds of his own money for assistance to the army, and induced several dozen of his friends to be similarly generous. It was not only necessary, but it was also nation-saving. In the previous ten months, the Continental dollar had been devalued forty to one, and then later 65 to one. No one would trust such a currency, whose consequence was certain to be a military disaster. But Morris obviously also knew that winning a war run by private subscription was unlikely to last much longer than one which depended on inflated paper currency and price controls. Petaliah Webster, a brilliant economist for the day, published pamphlets sarcastically comparing price controls to the religious conversion of a prisoner on a torture rack.

Therefore, passing the hat was also only an expedient. A week later Morris reorganized the concept to be The Pennsylvania Bank, where variable interest rates would induce reluctant lenders to lend. It was perhaps one or two steps better than losing the war, but it was primitive and limited. So, although Morris had originally opposed the war for independence, and the public certainly wasn't thrilled with taxes, market-driven interest rates were about all the Continental Congress would tolerate, as a compromise between confiscation and begging. The principle of free-market interest rates worked, in the sense that the army was able to fight on for several more years, but ultimately the soldiers revolted for lack of pay. It was notable that the Pennsylvania Line led the mutiny, or protest march, from Newburgh NY to the doors of Congress, and George Washington came close to giving the troops his tacit approval.

|

| The Bank of North America |

Well before matters came to that crisis, The Bank of North America, similarly attracting risk money by paying interest, was established in 1781 with an additional feature of generating side revenue through commercial 30-60 day loans. It was brilliant politics since Congress (with difficulty) agreed to permit a private company to engage in commerce but would never have tolerated the government doing so. When the goal is to transfer money from the private sector to the public one, the public insists on the ability to limit the amount. Otherwise, the transfer is a confiscation. Morris soon realized there was a missing third step. If the wealth of the nation was pledged to repay the war debts, creditors would insist on knowing the government's plans for repayment in case the bank couldn't do it. With the states retaining the right to tax but refusing the Federal government the right to tax without permission, the bonds of the Bank of North America were riskier for investors than they needed to be. In the difficult later years of the war, dependence on French loans began to look unwise, so the inability of the Federal government to confiscate private assets began to worry creditors. Somehow, Morris seemed to think the unratified Articles of Confederation were the problem and forced their ratification five years late. It didn't help matters, however, finally making it clear that the debt problem could not be solved without a new Constitution. When the soldiers did start to revolt, it became absolutely necessary to do something. Ultimately, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 was the result. In the meantime, the United States almost did collapse after the Battle of Yorktown (1783), and the French Revolution of 1789 is plausibly blamed in large part on our failure to repay the huge French financial support of our independence. A nation which pledges its full faith and credit behind war bonds must somehow convince its creditors that it intends to repay its bondholders, almost as fully as it intends to survive the war.

of pledging the full faith and credit of the nation through imposing taxes as lender of last resort. You don't need to pay for the whole war with loans, but you do need to reassure creditors that you will tax to repay your debts rather than default on them. That is, loan repayment is placed "ahead" of taxation. If even that structure proves inadequate, well, your war is simply not winnable because it provokes a dissolution of the government. The American public in 1781 did not need to understand the logic; it had just watched the process in grisly action. The public would not accept banks backed by federal taxation except as a wartime expedient, and therefore Robert Morris failed in his most important proposal. Although he continued to press for this essential feature for nine more years until it finally succeeded, a second near-miracle was that he kept the nation solvent in the meantime. He achieved this with a breath-taking combination of expedients, energy, ingenious fixes, and bluff. But the Treaty of Paris did not come a day too soon. In characteristic fashion, he did a quick about-face and proceeded to manage a huge personal fortune during a post-war convulsion.

In late 1779, before Morris would accept the job of rescuing the finances of the floundering new Republic, however, he meant to set some things straight. Congress must therefore first agree:

-- That Robert Morris would not accept the job unless Congress agreed that he could retain all of his private partnerships. Ben Franklin had warned him how ungrateful the public could quickly become, and what a short memory it had for those who performed favors. The Congress was infuriated by such demands, but Morris was adamant. Lucky for him that he was, because his enemies soon emerged with that age-old question, "Yes, but what have you done for us, lately? " -- That Morris has the power to dismiss any and all persons concerned with public finances and the public tender laws, for a cause. --That it was acknowledged that he assumed responsibility only for new debts, not those which preceded his taking office. -- That he has the right to delay taking the oath of office, retaining his seat in the Pennsylvania Legislature, until the relationship was clarified to give him effective control of state finances.

It can be imagined how displeased the Congress was with these high-handed stipulations, but they agreed to them.

Within three days of assuming office, -- Morris announced plans for the Bank of North America, our first true bank. -- Asked two personal friends, Thomas Lowrey, and Philip Schuyler, to buy one thousand barrels of flour on their own credit. He added, "I must also pledge myself to you, which I do most solemnly as an Officer of the Public. But lest you like some others believe more in private than in public credit I hereby pledge myself to pay you the cost and charges of the flour in hard money." -- Argued eleven points against the issuance of more paper money, particularly its requirement to be accepted as legal tender: "Because the value of money and particularly of paper money, depends upon the public confidence, and where that is wanting, laws cannot support it, and much less penal laws. . . Penalties on not receiving paper money must from the nature of the thing be either unnecessary or unjust. If the paper is of full value, it will pass current without such penalties, and if it is not of full value, compelling the acceptance of it is iniquitous." -- Arranged for the sale of western lands, to raise money. -- Acknowledged the Army was owed its back pay. -- Changed the War, Marine, Treasury, Foreign Affairs from committees of Congress to permanent departments.

A Change of Era

A maxim of the book-editor trade is "Deviate from chronology at your peril." Two events may have little to do with each other, but it always remains possible to show the earlier event had somehow affected the later one. An editor may know little about a topic, but he knows that much.

|

| Dean Donald Kagan |

In 2011, I was privileged to be a tuition-paying student at one of Yale's Directed Studies Courses. An invention of former Dean Donald Kagan, the DS courses take an important era in history and apply three conventional faculty disciplines to it at once: Philosophy, History, and Literature. For the undergraduates, courses range in chronology from Ancient Greek to the Enlightenment; so far, the alumni just get the Greeks. Judging only from the course in Ancient Greek, the unspoken thesis soon emerged that a major era experiences permanent changes in history, philosophy, and literature, but the connection between the three is often loose, requiring some pondering to make the connections firm. Aeschylus does have a connection with Plato, and Aristotle with Thucydides but it remains unclear why the connection exists. Furthermore, you can lump these things or split them; Ancient Greece fits naturally with the Roman Empire, but it can also stand alone. Therefore, although the Yale faculty tends to lump the American Revolution with The Enlightenment, a consideration of the life and times of Robert Morris, Jr. fits naturally with both the Enlightenment and the American Era, because the American part of the Enlightenment bifurcates abruptly when Morris stood in debate with William Findlay in the Pennsylvania State House in 1798 -- and lost.

|

| Robert Morris |

Morris was the richest man in America or close to it, the unofficial President of the United States in its darkest hours, the most brilliant non-academic innovator in Western Finance, the leader of American high society, the only man beside Roger Sherman to sign the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. Morris did not realize it but he was within a few months of going to jail for three years, then spending his final five years in secluded disgrace. Robert Morris was not accustomed to closing arguments, but he lost this one, concerning the wisdom of renewing the charter of the Bank of North America, the first real bank of the country. He lost an argument he should have won easily. In retrospect, the new modern American Era was beginning, and he was apparently on the wrong side of it. Politically, that is. Speaking purely of banking and finance, he was a century ahead of his time.

|

| Ancient Greek Gods |

It seemed to me and my alumni classmates that the idea of examining a historical period like the ancient Greek one in the light of three different academic disciplines, gradually assumed considerable merit. The philosophy department examined beliefs which underlay action, and the history department described what those actions turned out to mean inhuman affairs. But the literature department came far closer than either of the other two, to imparting to a reader just what it was like to be an ancient Greek. Professor Kagan seems to have a really good idea here, although it must be resource-expensive to develop, academically. Three departments of Academia have to come to some sort of agreement about the whole synthesis, an agreement which surely must not have been present at the start. It must be a process highly similar to a medical school teaching about a disease, with coordinated input from pathologists, surgeons, and internists. A nice idea, but terribly labor-intensive of labor of the highest quality. Book editors would say it is safer to stick with chronology as an organizing principle if you plan to do a lot of organizing. Nevertheless, I must express my gratitude to Yale for allowing me to be a spectator at an experiment conducted by masters of the thinking trade. Its results must be judged by standards other than the usual ones.

Constitutional Liberty

WITH British troops in the process of disembarking at New Brunswick, apparently intent on hanging rebels, Robert Morris and John Dickinson annoyed everybody by refusing to sign the Declaration of Independence. Both were fully engaged in the Revolution after the fighting finally got started, and Morris signed up in August 1776. Dickinson had some further reasons of his own, but Morris explained his position quite succinctly. He didn't mind being a British subject, he didn't want a new King, what he wanted was Constitutional Liberty. There is no record of his being directly confronted about this later, and thus no detailed explanation. But whatever did he mean?

|

| Iliad and the Odyssey |

Morris was of course very bright, even brilliant as a businessman. He had an astonishing memory for detail and was capable of holding his own counsel. He was a person of great daring and prodigious amounts of work. But there is very little evidence that he thought it was useful to be mysterious, or deep. So why not take him at his word, which was essentially that what mattered in a government was whether it kept its promises and allowed its citizens all possible Liberty. It did not matter whether the government had a king, or seldom mattered much who that king was. What mattered was whether it kept its promises, and for that a Constitution is useful. There is no great pleasure in being capricious and arbitrary, so a king who leaves the citizens alone is mostly the best you can ask for. It does, however, help considerably if the rules are fair, clear, and binding. Beyond that, it is unwise to go about toppling governments in the vain hope that a new one is somehow better than the old one. This is putting words into his mouth, to be sure. What he did say was he saw no advantage to getting a new government when what we wanted was Constitutional Liberty. Eleven years later, he was a personal friend of just about everyone with the power to design a new government. Washington lived in his house, or in one next door. Ben Franklin was a business partner. Gouverneur Morris was his lawyer and partner. Just about everybody else who mattered was meeting with him in secrecy for months at a time, in the Pennsylvania Statehouse. And so on.

An essential part of this puzzle of Morris' role could be that the American Constitution was very close to unique in being written out as a document, like a commercial contract. The British Constitution was unwritten at the time and continues to be unwritten today. Many other members of the British Commonwealth operate without a written constitution. And in fact, what passed as constitutions for thousands of years have been unwritten; it was the written American one which was the novelty, not the other way around. It may stretch matters a little to describe the Iliad and the Odyssey as constitutions, but they do in fact describe the system of governance of the Ancient Greeks, clarifying many axioms of their culture for which they were willing to fight and die. We are able to understand the rules for Greeks to live by from reading Homer, almost surely better than we understand the rules of American culture by reading The Federalist Papers. Modern students of geometry, for another example, are taught that all the rules of Euclidian geometry are based on a few axioms stated at its beginning. Change one of those axioms, and you make mathematics unrecognizable. Even Newton's Principia are now seen by mathematicians to be rules which apply only to our universe for certain. There may exist many other universes to which they do not apply. Axioms are themselves mostly regarded as unprovable assumptions. A Constitution, therefore, is regarded in modern times to be much the same thing as a set of mathematical axioms. With one new exception: they are written out on a piece of paper for all to see and agree to -- just like a commercial contract. It would not be surprising to discover that America's great merchant trader, Robert Morris, was horrified at the idea of depending on Vestal Virgins or Judges, or Kings, for their recollection of what the contract says. It, therefore, seems quite natural for a maritime merchant to be agitated by having the rules of British society depend on what King George III chose to emphasize or ignore. Write it down, negotiate it, then tell us what you want so we can agree to it; that's a proper way to define Constitutional Liberty and limit disputes. International maritime trade could not be conducted in any other way, because sea captains who feel abused in a foreign port can abruptly up-anchor and sail away, never to return to that port again until or unless local rules are clarified.

Unless someone discovers some relevant documents in a trunk in the attic, that's about the best conjecture to be made about the American novelty of a written constitution, and its transformative effect on the legal system of all other nations which have one. It would still be nice to know, for certain, whose idea it was.

Limits of Leverage

|

| Continental Congress |

PHILADELPHIA was the seat of the Continental Congress, hence the nation's capital, from 1774 to 1790, with two periods of abandonment. After the ratification of the Articles of Confederation in 1781, it became the Confederation Congress. When the British had occupied the city in 1777-78, "the Congress" fled to Baltimore, then to York, Pennsylvania, but returned as soon as the British left. The second period of the flight was occasioned by the near-mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line for lack of pay in 1783, when Congress fled, in succession, to Annapolis, Trenton, Princeton, and New York, leaving General Washington's loyalties torn between sympathy for his starving troops, and firm loyalty to law and order. The chaotic situation suited the British, who dragged out peace negotiations after the Battle of Yorktown and came close to winning by stalling what they had been unable to achieve by arms. The finances of the French government were already stretched beyond what was prudent in view of their intention to invade the British Isles. The much more solvent British began to see India as a more attractive colony than America, particularly if the lucrative trade with Jamaica and other Caribbean islands could be maintained without the expenses of the rebellion. Eight years is a long time for any nation to continue a war without generating significant unrest at home.

The Constitution did not change taxation much; it changed the people who control our borrowing.

|

|

| Revolutionary War |

So, although the Revolutionary War was primarily started by British bungling which incited intemperate colonial hotheads into rash behavior, it was going to require a new Constitution and a realistic agreement about everybody's future, to achieve a workable peace. At the beginning of hostilities, only Robert Morris and John Dickinson talked as though they had done some clear long-term thinking, and they both opposed declaring Independence. They were shouted down and forced to go along or be banished. After eight years of fighting, however, a great many people could see that Dickinson may have been right to question the dubious unity of thirteen colonies, while a smaller group could even see that Morris might have been right to focus on Constitutional Liberty rather than regime change. Washington, although he was afraid of little else was fearful about his lack of education beyond grammar school; but at least he knew a country which would not feed its soldiers must be doomed to be no country at all. James Madison was scholarly and knew about Constitutions back to Aristotle, although events proved he had offered himself as a constitutional technician without clear personal goals for the product. Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris were adventurers, quite willing to shrug off the slogans of war and establish a king, that one form of government they were sure was workable. Only Benjamin Franklin among the colonists had stood before five kings, and of course before Vergennes and Wedderburn, where he could observe that all forms of government were in the hands of agents and intermediaries. But Robert Morris was a businessman who probably wanted little more than a workable set of rules, a level playing field, where he had every confidence that he would win, regardless of other rules for the game. Those rules at a minimum must include an equitable means for the government to pay its debts. As the richest delegate, in his own city, he was encouraged to act as a host for the convention. As host, he felt constrained to speak only about finance, his main concern anyway. Once this point was established fairly early at the Constitutional Convention, Morris had little else to say, even though he personally had many irons in the fire. Everything else, as politicians say, was for sale. Besides which he was accompanied by his personal lawyer but no relation, Gouverneur Morris, who was by far the most elegant speaker and persuasive advocate in the group.

Or perhaps the true flavor of his approach was, One Thing at a Time. Robert Morris was elected U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania in the first Congress under the new Constitution. He was in the center of almost every major debate, member of more than forty committees, often described as running on and off the floor, marshaling votes. The assumption of state Revolutionary War debts was perhaps part of his central drive to establish the full faith and credit of the United States. But the location of the new capital was quite a separate issue. Morris had bought huge acreage across Delaware from Trenton, in the area now known as Morrisville, and he lobbied hard and long to have the Capital located in Trenton, just as Senator Maclay lobbied to have it settle on his own land near Harrisburg. The New York congressional delegation, led by Alexander Hamilton, fought for a New York location, although Gouverneur Morris attempted to favor his own estate, Morrisania, in the Bronx. And of course, it was the Virginia delegation which finally won the prize, on the Potomac opposite George Washington's estate at Mt. Vernon. The location of the capital was important to Robert Morris, but as a realist, he then bought up large tracts of land in the District of Columbia. Owning two sites for a national capital at the same time was a major overextension of Morris' debts which helped lead to his final bankruptcy, although he was involved in so many affairs it is hard to say which was most significant. And indeed, his lobbying from debtors prison was the main source of a new bankruptcy law, which released him from prison. When Morris was seated in the Constitutional Convention, a large number of ideas must have been running through his head. But as far as we can tell, he largely held his peace, apparently content with the significant achievement of establishing federal taxation. Robert Morris had more ideas than anybody, and more energy than was good for him.

Over the centuries, the Constitution has been seen as a marvel of concise prose. Events have reversed the position of the political parties many times, but the Constitution does not change, so much as its meaning evolves. In the case of the federal ability to tax, however, almost nothing matches its malleability. The Revolutionary War was begun in large part because of a two-cent tax on tea, which was in fact a lowering of the tax rate. By the time of the Presidency of James Monroe, the federal debt had been extinguished by national prosperity. By the time of the Presidency of Barack Obama, the economy of the whole world, not just this one nation, is threatened by excessive indebtedness. The brilliant insights of Morris and Alexander Hamilton thus leveraged the industrial world into a situation which was unimaginable in the Eighteenth century. We are today nearly forced into economic recession, in order to pay down the national debt which computers concealed from us. If our creditors lose the faith we can reduce the debt, they will raise interest rates beyond the point where even the present debt can be sustained. The Constitution did not change taxation much; it changed the people who control our borrowing. The borrower is on a long leash, but creditors hold the other end of it.

Tax References in the 1787 Constitution: Article 1, Section 2: Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. Section. 7. All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives, but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills. Section. 8. The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts, and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States; To borrow Money on the credit of the United States; To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes; To establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States; To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures; To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States; To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof. Section. 9. The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person. The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it. No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed. No Capitation or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken. No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State. No Preference shall be given by any Regulation of Commerce or Revenue to the Ports of one State over those of another; nor shall Vessels bound to, or from, one State, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay Duties in another. No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time. Section. 10. No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility. No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it's inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the United States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Control of the Congress.

|

Pennsylvania's First Industrial Revolution

|

| David Thomas |

We tend to think of 1776 as the beginning of American history, but in fact, the region around Easton was settled a hundred-forty years before 1776, and the forests were pretty well lumbered out. The backwoods lumbermen around the junction of the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers were about to move further west when Washington crossed Delaware and fought the battle of Trenton. This region nevertheless had three essential ingredients for becoming the "Arsenal of the Revolution": It was close to the war zone but protected by mountains, it had a network of rivers, and it had coal. The hard coal of Anthracite had the problem it was slow to catch fire, and iron making in the region didn't really get started big-time until a Welsh iron maker named David Thomas discovered that anthracite for iron making would work if the air blast was pre-heated before introducing it into a "blast" furnace. A local iron maker traveled to England to license the patent from Thomas, whereupon Thomas' wife persuaded her husband to move to Pennsylvania. Blast furnaces only got started into production by 1840, but by 1870 there were 55 furnaces along the Lehigh Canal. For thirty years this was America's greatest iron-producing region. In fact, Bethlehem Steel only closed its last plant in 1995.

|

| Canal Boat |

When iron-making got started, the local industrial revolution really took off, but the more fundamental step was to dig canals to transport the coal to other regions. Canals were the dominant form of transportation for only thirty years until railroads took over, and the entire Northeast of the nation was laced with canals. Curiously, the South had relatively few canals, so their industrialization was too late for canals, and too early for railroads, to help much in the Civil War. The Erie Canal was the big winner, but Pennsylvania had many networks of canals in competition, leading to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, whereas the Erie Canal was more headed toward the Great Lakes and Chicago. Eventually, J.P. Morgan put an end to this race by financing the Pennsylvania Railroad and moving the steel industry to Pittsburgh, where bituminous coal was the fuel of choice. This industrial rivalry was at the heart of the enduring rivalry of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, as well as the commercial rivalry between New York and Philadelphia. It was more or less the end of the flourishing economy of the "Reach" including Easton, Bethlehem, and Allentown. A reach is a geographic unit sort of bigger than a county, in local parlance. But you might as well include the city of Reading, which concentrated more on railroads and commerce with the Dutch Country. Out of danger from the British Fleet on the ocean, but close enough for war, the "reach" was more or less the forerunner of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Vietnam in several later wars. The Lehigh Canal stretched from Easton to Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe), the so-called Switzerland of Pennsylvania, only a mile or two West of the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

|

| Blue Mountain |

The Allegheny Mountains stretch across the State of Pennsylvania, and the most easterly of these mountains is locally called "Blue" mountain because of its hazy appearance from the East when seen across a lush and prosperous coastal plain. It represents the farthest extent of the several glaciers in the region, and the two sides of it present quite a sociological contrast. The Pennsylvania Dutch found themselves on the richest farming land in the world, whereas the inhabitants of the other side of the mountain had to subsist on pebbles. The mountain levels down at the Delaware River, so the Dutch farmers and the late immigrants from Central Europe mixed, in the time and region of industrial prosperity. Gradually, the miners and the steelworkers began to drift away, but the Pennsylvania Germans tended to remain where they had been before all the fuss. So the Kutztown Fair is full of Seven Sweets and Seven Sours, the farmhouses are large and ample, and mostly remain the way they were, too. You have little trouble finding a twang of Pennsylvania Dutch accents. But Bucks County in Pennsylvania was cut in half by the glacier, and north of the borderline, you can see lots of pickup trucks with gun racks behind the driver. Everything is amicable, you understand, but for some reason, the tax revenues of the two halves of the County are forbidden to be transferred, even within the same county. Better that way.

|

| Lehigh Marker |

The Lehigh River runs along the North side of Blue Mountain, and trickles down to join the Delaware at the town of Easton. There were only 11 houses in the town in 1776, and now you can see several miles of formerly elegant early Nineteenth century townhouses. At the point where the two rivers join, a lovely little park has been built to celebrate the high point of Colonial canal-making. Hugh Moore, the founder of the Dixie Cup Company is responsible for this historic memory, well worth a trip to see. If you have called ahead for reservations, you can have a genuine canal boat ride, pulled by two genuine mules. When you hear that the boat captain and his family used to live on the boat (Poppa steered, Momma, cooked, and the children tended the mules), it seems small and cramped. But when you climb aboard, you find it holds a hundred people for dinner with plates in their laps. The food is partly Polish, partly Hungarian and partly other things Central European. And the captain plays guitar and fiddle, singing old songs he mostly composed himself. Surprisingly, no Stephen Foster, who held forth about four hundred miles to the West, until he drank himself to death at Bellevue Hospital in New York. Foster was a member of a rival tribe of canal boaters, the ones who traveled down to Pittsburgh via the Erie Canal. Along the Reach, you hear about three canals, the Lehigh, Delaware, and Morris. The first two are obvious enough since they and the railroads which subsequently followed ran along the banks of two rivers joined. The Morris was Robert Morris, at one time the richest man in America, who bought Morrisville across from Trenton on the speculation he could persuade his friends to put the Nation's Capital there. It didn't work out, so he bought and went broke with the District of Columbia. Anyway, the Morris canal went on to New York harbor, where it prospered mightily shipping iron to New York, and iron for the rolling mills of Boston. The Morris Canal went over the Delaware River on a bridge that carried an aqueduct, over to Philipsburg; and then across the wasp waist of New Jersey.

Robert Morris and the Lee Brothers

* * *

Morris was a monarchist, announcing he liked the king and did not want to change him. The Lees, one surmises, though they might make pretty good kings, themselves.

But we get far ahead of the story. The immediate mystery is Morris' behavior in July, 1776.

|

| Robert Morris |

The dominant feeling during 1775 had been that Americans needed to prepare for war while doing everything possible to avert it. If England prevented both the manufacture and importation of gunpowder in the colonies, there was no way to be prepared for war except to smuggle gunpowder. Not to smuggle it would leave the colonies weak, almost inviting abuse from London. In several elections, before then Morris had been the nominee of both the radicals and the conservatives. The radicals could see he was an energetic, efficient and close-mouthed international shipowner; when a Secret Committee was proposed, he obviously would be an effective member of it. But he was loudly opposed to war with England and was formidable in a debate. The conservatives might have felt he would keep the hotheads on the committee from wandering from or expanding its narrow charge. He explained his dual position as seeking "Constitutional Liberty" rather than independence, but that was shrugged off as just so much blather. It would be twelve years before people did understand what he wanted, and that he was entirely serious about it. That the Lee brothers didn't ever understand, didn't bother Morris at all. That the Lee brothers couldn't comprehend his unwillingness to charge headlong into battle, unarmed and unprepared, was equally mysterious to Morris. The Lee brothers would well have understood Napoleon's remark that victory was 10% based on surprise. But what Napoleon is thought to have said was that victory was 90% based on supplies.

|

| Arthur Lee |