2 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

French Philadelphia

French Philadelphia

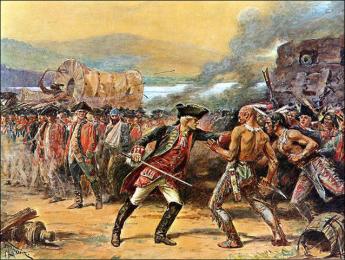

Politics of the French and Indian War

|

| Isaac Sharpless |

In the European view, the French and Indian War was a mere skirmish in the many-year conflict between France and England. But the Atlantic is a wide ocean. The local Pennsylvania politics of that war concern the land-hungry settlers striving for Indian lands, the Quaker Assembly doing its best to maintain William Penn's formula for peace ("No settlements without first buying the land from the Indians."), and William Penn's far-from-idealistic Anglican sons, focused on profit from a land rush. Western Pennsylvania belonged to the Delaware tribe, but the Delawares were subject to the Iroquois nation. The year is 1754. The following pro-Quaker description is given by Isaac Sharpless, president of the Quaker Haverford College between 1887 and 1917 (Political Leaders of Colonial Pennsylvania,

|

| Isaac Norris |

Isaac Norris was appointed to another Albany treaty with the Indians in 1754. The commission consisted of John Penn and Richard Peters representing the Proprietors, and Benjamin Franklin and himself, the Assembly. Indian relations were becoming difficult. The Five Nations still claimed the right to the ownership of Pennsylvania and insisted that no sale of land by the Delawares was permissible. In an evil hour, the government of Pennsylvania recognized this claim and this Albany meeting was for the purpose of effecting a purchase. By methods that were more or less unfair, taking advantage of the Indian ignorance of geography, they bought for 400 pounds all of southwestern Pennsylvania. When the Delawares found their land had been sold without their consent, they threw off the Iroquois yoke, joined the French, defeated Braddock's army a year later and for the first time in the history of the Colony the horrors of Indian warfare were known on the frontiers.

Although Sharpless goes directly to the unvarnished truth of the situation, he reveals the depth of his bitterness by openly discarding Franklin's cover story about being in Albany to propose political unity among the British colonies.

It was on this expedition that Franklin presented to his fellow delegates his plan for a union of the Colonies, of course in subordination to the British Crown which was a precursor of the final union in Revolutionary days. Sixty years earlier William Penn had proposed a somewhat similar scheme.

The war came, French intrigue and the unwisdom of the Executive branch of the government of the Province (the Penns) drove the Indians, who for seventy-three years had been friendly, into the warpath. Cries came in from the frontiers of homesteads burnt, men shot at their plows, women, and children scalped or carried into horrible captivity, and a growing sentiment among the red men that the French were the stronger and that the English were to be driven into the sea.

Germantown and the French and Indian War

|

| The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army |

Allegheny Mountains from which to trade with, and possibly convert the Indians, the French had a rather elegant strategy for controlling the center of the continent. It involved urging their Indian allies to attack and harass the English-speaking settlements along the frontier, admittedly a nasty business. The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army at what is now Pittsburgh reported hearing screams for several days as the prisoners were burned at the stake. Rape, scalping and kidnapping children were standard practice, intended to intimidate the enemy. The combative Scotch-Irish settlers beyond the Susquehanna, which was then the frontier, were never terribly congenial with the pacifism of the Eastern Quaker-dominated legislature. The plain fact is, they rather liked to fight dirty, and gouging of eyes was almost their ultimate goal in any mortal dispute. They had an unattractive habit of inflicting what they called the "fishhook", involving thrusting fingers down an enemy's throat and tearing out his tonsils. As might be imagined, the English Quakers in Philadelphia and the German Quakers in Germantown were instinctively hesitant to take the side of every such white man in every dispute with any redone. For their part, the Scotch-Irish frontiersmen were infuriated at what they believed was an unwillingness of the sappy English Quaker-dominated legislature to come to their defense. Meanwhile, the French pushed Eastward across Pennsylvania, almost coming to the edge of Lancaster County before being repulsed and ultimately defeated by the British.

In December 1763, once the French and Iroquois were safely out of range, a group of settlers from Paxtang Township in Dauphin County attacked the peaceable local Conestoga Indian tribe and totally exterminated them. Fourteen Indian survivors took refuge in the Lancaster jail, but the Paxtang Boys searched them out and killed them, too. Then, they marched to Philadelphia to demand greater protection -- for the settlers. Benjamin Franklin was one of the leaders who came to meet them and promised that he would persuade the legislature to give frontiersmen greater representation, and would pay a bounty on Indian scalps.

Very little is usually mentioned about Franklin's personal role in provoking some of this warfare, especially the massacre of Braddock's troops. The Rosenbach Museum today contains an interesting record of his activities at the Conference of Albany. Isaac Norris wrote a daily diary on the unprinted side of his copy of Poor Richard's Almanac while accompanying Franklin and John Penn to the Albany meeting. He records that Franklin persuaded the Iroquois to sell all of western Pennsylvania to the Penn proprietors for a pittance. The Delaware tribe, who really owned the land, were infuriated and went on the warpath on the side of the French at Fort Duquesne. There may thus have been some justice in 1789 when the Penns were obliged to sell 21 million acres to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for a penny an acre.

Subsequently, Franklin became active in raising troops and serving as a soldier. He argued that thirteen divided colonies could not easily maintain a coordinated defense against the unified French strategy, and called upon the colonial meeting in Albany to propose a united confederation. The Albany Convention agreed with Franklin, but not a single suspicious colony ratified the plan, and Franklin was disgusted with them. Out of all this, Franklin emerged strongly anti-French, strongly pro-British, and not a little skeptical of colonial self-rule. Too little has been written about the agonizing self-doubt he must have experienced when all of these viewpoints had to be reversed in 1775, during the nine months between his public humiliation at Whitehall, and his sailing off to meet the Continental Congress. Furthermore, as leader of a political party in the Pennsylvania Legislature, he also became vexed by the tendency of the German Pennsylvanians to vote in harmony with the Philadelphia Quakers, and against the interest of the Scotch-Irish who were eventually the principal supporters of the Revolutionary War. It must here be noticed that Franklin's main competitor in the printing and publishing business was the Sower family in Germantown. Franklin persuaded a number of leading English non-Quakers that the Germans were a coarse and brutish lot, ignorant and illiterate. If they could be sent to English-speaking schools, perhaps they could gradually be won over to a different form of politics.

Since the Germans of Germantown was supremely proud of their intellectual attainments, they were infuriated by Franklin's school proposal. Their response was almost a classic episode of Quaker passive-aggressive warfare. They organized the Union School, just off Market Square. It was eventually to become Germantown Academy. Its instruction and curriculum were so outstanding as to justify the claim that it was the finest school in America at the time. Later on, George Washington would send his adopted son (Parke Custis) to school there. In 1958 the Academy moved to Fort Washington, but needless to say, the offensive idea of forcing the local "ignorant" Germans to go to a proper English school was rapidly shelved. This whole episode and the concept of "steely meekness" which it reflects might be mirrored in the Japanese response, two centuries later, to our nuclear attack. Without the slightest indication of reproach, the Japanese wordlessly achieved the reconstruction of Hiroshima as now the most beautiful city in the modern world.

Washington Lurks in Bucks County, Waiting for Howe to Make a Move

|

| Moland House |

Although Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is staunchly Republican, it has been home to Broadway playwrights for decades; this handful of Democrats have long been referred to as lions in a den of Daniels. One of them really ought to make a comic play out of the two weeks in August 1777, when John Moland's house in Warwick Township was the headquarters of the Continental Army.

John Moland died in 1762, but his personality hovered over his house for many years. He was a lawyer, trained at the Inner Temple and thus one of the few lawyers in American who had gone to law school. He is best known today as the mentor for John Dickinson, the author of the Articles of Confederation. Our playwright might note that Dickinson played a strong role in the Declaration of Independence, but then refused to sign it. Moland, for his part, stipulated in his will that his wife would be the life tenant of his house, provided -- that she never speak to his eldest son.

Enter George Washington on horseback, dithering about the plans of the Howe brothers, accompanied by seven generals of fame, and twenty-six mounted bodyguards. Mrs. Moland made him sleep on the floor with the rest.

Enter a messenger; Lord Howe's fleet had been sighted off Patuxent, Maryland. Washington declared it was a feint, and Howe would soon turn around and join Burgoyne on the Hudson River. Washington had his usual bottle of Madeira with supper.

A court-martial was held for "Light Horse Harry" Lee, for cowardice. Lee was exonerated.

Kasimir Pulaski made himself known to the General, offering a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, which letters Franklin noted had been requested by Pulaski himself. As it turned out, Pulaski subsequently distinguished himself as the father of the American cavalry and was killed at the Battle of Savannah.

|

| Lafayette |

And then a 19 year-old French aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette, made an appearance. Unable to speak a word of English, he nevertheless made it clear that he expected to be made a Major General in spite of having zero battlefield experience. He presented a letter from Silas Deane, in spite of Washington having complained he was tired of Ambassadors in Paris sending a stream of unqualified fortune hunters to pester the fighting army. Deane did, however, manage to make it clear that the Marquis had two unusually strong military credentials. He was immensely rich, and he was a dancing partner, ahem, of Marie Antoinette.

In Mrs. Moland's parlor, Washington sat down with Lafayette to tap-dance around his new diplomatic problem. It was clear America needed France as an ally, and particularly needed money to buy supplies. But it was also clearly impossible to take a regiment away from some American general, a veteran of real fighting, and give that regiment to a Frenchman who could not speak English and who admitted he had no military experience. Fumbling around, Washington offered him the title of Major General, but without any soldiers under his command, at least until later when his English improved. To sweeten it a little, Washington seems to have said something to the effect that Lafayette should think of Washington as talking to him as if he were his father. There, that should do it.

It seems just barely possible that Lafayette misunderstood the words. At any rate, he promptly wrote everybody he knew -- and he knew lots of important people -- that he was the adopted son of George Washington.

Well, Broadway, you take it from there. At about that moment, another messenger arrived, announcing Lord Howe at this moment was unloading troops at Elkton, Maryland. General Howe might have been able to present his credentials to Moland House in person, except that his horses were nearly crippled from spending three weeks in the hold of a ship and needed time to recover. Heavy rains were coming.

(Exunt Omnes).

Suggested Stage Manager: Warren Williams

La Fayette, We Are Here

|

| Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette |

It will be recalled that La Fayette was 19 years old at Valley Forge, spoke no English, had no previous military experience. He nevertheless demanded, and got, a commission as Major General on the prudent condition that he have no troops under his command, at least for a while. Washington had been strongly reminded by various people that this young Frenchman was one of the richest men in France, a personal friend of the Queen, and thus critical to the project of enlisting French assistance in the war. Under the circumstances, it was shrewd to send him on the project of enlisting Indian allies among the Iroquois, since many tribes, particularly the Oneida, spoke French and held their former allies in the French and Indian War in great esteem. The chief of the Oneida Wolf clan (Honyere Tiwahenekarogwen) was visiting General Philip Schuyler in Albany at about the time LaFayette showed up on his mission to get some help for Valley Forge. General Horatio Gates was busy at the time rallying a colonist army to defend against the British under Burgoyne, coming down from Quebec, eventually to collide at the Battle of Saratoga.

Earlier in the war, Honyere's Oneida tribe had tangled with their fellow Iroquois under the leadership of Joseph Brandt (the Dartmouth graduate who was both biblical scholar and commander of several frontier massacres); the Oneida had many new scores to settle with the English-speaking Iroquois tribes. Honyere made the not unreasonable request that before his warriors went off to war, his new American allies would please build a fortification to protect his women and children from Brandt's Mohawks. LaFayette readily put up the money for this project, quickly becoming the Great French Father of the Oneidas. After some scouting and patrolling for Gates, Honyere and about fifty of his braves followed LaFayette to Valley Forge, where they soon made a nuisance of themselves to the Great White Father George Washington. Finally, word of the official French alliance with the colonists reached London, Howe was replaced by Clinton, and the British began to withdraw from their isolated position at Philadelphia.

It was thus that the jubilant rebels at Valley Forge learned that the fortunes of war had turned in their favor, and the French alliance was the source of it. With the British making preparation to abandon Philadelphia, it seemed a safe thing for Washington to give LaFayette command of two thousand troops, including the fifty Oneida Indians, and post them to Barren Hill (now LaFayette Hill), along Ridge Pike near Plymouth Meeting. Washington gave the strictest orders that they were to take no chances with anything, and particularly were to remain mobile, moving camp every day. This was not exactly what the richest man in France was anticipating, and wouldn't make a very saucy story to tell Marie Antoinette about. So, he promptly set about fortifying Barren Hill. Local Tory spies quickly spread this news to General Clinton, who promptly led eight thousand redcoats up the Ridge Pike to capture the bloody Frog. Clinton's plan was good; a detachment went around LaFayette in the woods and came back down Ridge Pike from the other direction, driving the Americans down the Pike into the open arms of the main body of British troops, coming up Ridge Pike. From this point onward, two entirely different stories have been told.

The more widely-held account has LaFayette climbing the steeple of the local church and noticing that there was an escape path, leading down the hill to the Schuylkill River at Matson's Ford. The Indian scouts were sent forward to hold off the British while the troops made their escape. Clinton sent a cavalry charge of Dragoons forward, yelling and waving their sabers, generally making a terrifying spectacle. The Indian scouts, as was their custom, were lying in the brush shoulder to shoulder, and at command by Honyere rose from the ground to let out a resounding chorus of war whoops. The Indians had never seen a cavalry charge, the Dragoons had never heard a war whoop, so both sides fled the battlefield without doing much damage. Meanwhile, LaFayette and his troops escaped to safety on the far side of the Schuylkill.

Other accounts of this episode relate that when Washington heard of it he remarked sourly that either they were pretty lucky, or else the enemy was pretty sluggish. In any event, a few soldiers were killed on both sides, the Americans crossing the River were described as "kegs bobbing on the pond", and it does seem the British army mostly just watched them do it. In the confusion, of course, everyone involved was fearful of being surrounded by unseen troops, and the British may well have worried the whole thing was a trap.

The saddest postscript to the Battle of Barren Hill is the fate of the Indians. After the war was over in 1783, the colonists busied themselves with taking over Indian land. Honyere pitifully petitioned the New York legislature for some consideration of his tribe's wartime service. They ignored him.

Franklin in Paris

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Adlai Stevenson once observed that every diplomat must make a solemn pledge -- to drink for his country. Ambassadors represent their country to chiefs of state, and everybody involved must participate in constant social masquerades to ease the strain of dealing with people whose interests may conflict with his own. In fact, when some ambassador indelicately blurts out the truth, he can be expected to be declared "persona non grata", and replaced.

There are plenty of reasons to suppose that Franklin disliked the French. On several occasions, he had rallied public opinion, raised troops and even served in the Colonial forces during the French and Indian War. As a leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly, he had to cope with the activities of the French in western Pennsylvania, stirring up Indian massacres of Pennsylvania settlers. He very nearly lost his financial shirt helping General Braddock obtain horses and wagons, and surely had numerous acquaintances in the British Army slaughtered at Fort Duquesne. England was at war with France for years, and right up to 1774, Franklin spent most of his energies trying to bring the Colonies into tighter unity with the British throne. The purpose of such a union was primarily to ensure the protection of the Colonies against the French. The goal was always to ensure the protection of the Colonies against the French.

Having spent seventy years building up defenses against the French bogeymen, Franklin's about-face had been abrupt. Right up to the moment of confrontation with Wedderburn in the cockpit of Whitehall, Franklin had been struggling with the English to make America a full part of Great Britain, searching for an acceptable formula for taxing America for its own defense -- against the French and Spanish. After his public humiliation and a brief interval of contemplation, Franklin went home to join the Second Continental Congress, spending only a few months there to bring Revolution to a tipping point. Having succeeded largely because of his assurance that he could get the French to become allies, he promptly returned to Paris to make good on his assurances. Maybe he was a secret French-lover all that time, and maybe his expedition to Paris was just a ruse to let him enjoy a ten-year Parisian vacation. But the utter implausibility of that suspicion is exposed merely by voicing it. Furthermore, he had spent many years at the British Court on his quest to take Pennsylvania from the Penn family and give it back to the King, therein receiving a full education in the wiles and deceits of diplomatic life. He knew what to do, how to dress, how to talk, and what to disassemble as a negotiator. He had seen many diplomats fail in their missions and had a chance to observe what it took for others to succeed. He was forty years older than almost anyone he met, world famous before most of them were born.

So the late Harvey Sicherman, Philadelphia's local State Department alumnus, was almost surely right when he described Franklin as a spinner. He may have grown to like some particular Frenchmen and Frenchwomen, and he certainly enjoyed himself hugely. But to say he loved France is a stretch, while to say he hated most things which are uniquely French is not totally improbable. More likely, he was indifferent to all that, because he was there to do a job. His job description was to make himself charming, attractive, and persuasive to as many influential Frenchmen as he could find. And to wait for any diplomatic opportunities which George Washington might create on some distant battlefield.

When he first arrived in Paris, the military situation back home was bleak. The British had just defeated Washington on Long Island, the expedition against Canada had been a failure. For ten months, Franklin had to keep the American vision alive in Paris without evidence of military success at home. When Washington finally defeated the British at Trenton and Princeton, and particularly when Burgoyne was routed at Saratoga, Franklin pounced. Those victories were exaggerated suitably and celebrated wildly throughout all the social circles which Franklin had charmed for the previous year. Scientific and intellectual leaders, salon society, and even many members of the royal court were on his Rolodex, so to speak. They were useful levers of gossip and news to spread his reports in a suitable way. Paris was full of spinners, spies, and manipulators, but Franklin the old publisher knew how to dominate the news.

Even his famous love affairs could be viewed as having their purpose. Madam Brillon was forty years younger than Franklin, one of the most beautiful and musically talented women of the age. No doubt it was pleasure itself to charm this charmer, and no doubt his advanced age caused her husband to drop his guard. But Franklin knew very well what a stir it would make for a famous man his age to be linked in speculative gossip to a thirty-two-year-old celebrated beauty. That he could have made this conquest in spite of old age, gout, kidney stones and a very rudimentary knowledge of French, was deliciously worth talking about in naughty circles. And then one never knows. In a time of war, surrounded by spies and assassins, it would always be a good thing to have local friends who might warn him, hide him or help with an escape.

Franklin's association with

|

| Madame Helvetius |

Madame Helvetius was much the same in many ways, or at least John Adams thought so, but there are some major differences. In fact, if you discount the parts that offended Adams as largely dissembled, the Helvetius episode may have been the most truly significant relationship of Franklin's life. She was widowed, much closer to him in age, much more his equal in wit and attainment, and he actually proposed marriage to her. She refused him, for reasons we are not in a position to assess, but a marriage between an Austrian relative of Marie Antoinette to an elderly frontiersman might well have seemed too far a social stretch. Furthermore, there seems to be an important connection between the intellectual circle of revolutionaries who clustered with her and her former husband, and the impending French Revolution. The mother of LaRochfoucauld also ran a salon for the same group, attended by LaFayette and others who turned up in America during our revolution, and who associated with others whose names would in time seem like a recital of the leaders of the French Revolution. Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were both active with this group of rebels whose history goes back to the reign of Louis XIV. Jefferson was obviously influenced by them, Franklin's intellect was so much more powerful that it is possible that influence ran the other way. The thought has occurred to others that Franklin may have been mainly responsible for two revolutions, not just one. Even two centuries later, feelings run so high that the truth of the matter is not clear. From the point of view of Franklin's diplomatic triumphs, the existence and power of this group of French conspirators do raise a question of just who was using whom. And whose goals were ultimately served.

In any event, Franklin was quick to turn the Battle of Saratoga into a decision by France to become an open ally of the colonists, and the Battle of Yorktown into the Treaty of Paris granting independence to America. During all the years in between, Franklin was wheedling money and munitions secretly from the French, somehow using Haym Salomon to get the money out of France and Holland, around the British navy, and into the hands of the beleaguered Americans. As always happens, the money suffered some shrinkage in transit, for which many fingers were pointed at many reputations, including Franklin's.

Stephen Girard 1750-1831

|

| Stephen Girard |

Girard was born in Bordeaux, France and never went to school. By the age of 23, he had become a sea captain, like his father and grandfather. By the age of 27, he owned his own ship and was thus launched on a successful career in a very dangerous occupation. Depending on the destination and weather during that era, up to forty percent of sailors were lost at sea on long voyages. From the point of view of the passengers and shippers, when you were selecting a captain you wanted one who had returned unharmed from many voyages. It was irrelevant whether he had been lucky, or diligent, or had learned a lot from his relatives in the trade.

Stephen Girard did start with a handicap, being born blind in one eye. It may have been a personality disorder which drove him to precise, minute instructions to his subordinates in excruciating detail; he might now be called a "control freak" and be disliked for it. For example, he kept a handwritten copy of all letters he wrote, and at his death, there were 14,000 of them, sorted and filed. His wife went insane, and after spending years at the Pennsylvania Hospital, was buried on the grounds. If this is the price of being rich, some might consider remaining poor. During his working years in Philadelphia, he would normally get to the counting-house at 5 AM, go to his bank at noon, and go to work on his 600-acre farm in South Philadelphia after 5 PM. He said he liked farm work the best. The image left behind by this role model, then, was workaholic. Nevertheless, if you wanted to become the richest man in America, here was the pattern to follow.

Girard probably came as close as any rich man in history, to "taking it with him" when he died. His innately compulsive personality, combined with the sure knowledge that his relatives and others would probably try to break his will for their own benefit, led to the construction of a last will and testament that withstood a century of court challenges. It launched remarkable philanthropy for thousands of orphans and organized the whole Delaware Valley into an industrial machine unlike anything else in the country. Although he left the largest estate in the nation's history, that estate continued to accumulate money from his minute instructions to executors, eventually enlarging his vast fortune fifty-fold, a century after his death. In retrospect, Philadelphia might well have slowly declined into obscurity after the nation's capital moved to Washington in 1800. Instead, the coal, canal, railroad and industrial empire of the Philadelphia region became the "arsenal of the North" during the Civil War, and the main wealth generator of the Gilded Age which followed.

Girard's business career can be somewhat oversimplified as consisting of shipping at the base of his early good fortune, followed by banking during the era when banking was poorly understood and usually ineptly managed. He ended his career with an eager and successful embrace of the emerging Industrial Revolution. Throughout all of this, he characteristically took great risks for great profits, through recognizing what others were too timid to accept fully. On many occasions, his risky ventures resulted in very large losses, made acceptable by other risky ventures proving unexpectedly successful. An example would be Girard's Bank. When the Federal Government first started and then abandoned the First National Bank Girard bought up the remnants and made a great private success of banking, where he had little previous experience. He saw the potential of the canals, and later the railroads when others were content to be farmers or country gentlemen. When he was 79 years old, he purchased vast tracts of wilderness containing some outcroppings of coal, because he could foresee a great industrial future for the region. No pain, no gain.

Another way of looking at Girard was as the most prominent French-American citizen of his time. He arrived in Philadelphia at about the same time Benjamin Franklin stepped off another boat, returning from abusive treatment by British officials which finally flipped him for American independence. Franklin recognized that independence from England meant an alliance with France, or else it meant defeat. It is possible to view the American Revolution as an episode of France searching for an American foothold after its expulsion fifteen years earlier in the French and Indian War; trouble between Britain and its colonies might re-open opportunities for France. Girard was extremely friendly with Thomas Jefferson, the most Francophile of founders and early American presidents. When the War of 1812 with Great Britain threatened disaster for the new American state, Girard staked $8 million dollars, his whole fortune, on financing that war. During the entire period from 1776 to the Louisiana Purchase, America was wavering between its gratitude to France and underlying loyalty to the English-speaking community. During that long formative period, Girard the very rich Frenchman was hovering in the background, probably influencing American foreign policy more than is known, even today. But the France that Girard stood for was neither aristocratic of the LaFayette variety nor intellectual of the Robespierre sort. It was France of the French peasant, crabbed, acquisitive, and morose, forever responding to a "hidden hand" of his own self-interest in a way that paradoxically benefited his whole community, and thus would have hugely amused the Scotsman Adam Smith.

Stephen Girard, Compulsive Gambler

|

| Stephen Girard |

Keep flipping a coin, it's unlikely to come up Heads eighteen times in a row, but it could happen. Once they get to be the richest in the country, most people would quit flipping rather than risk everything on the fifty-fifty chance the next flip will come up Tails. But Robert Morris, William Bingham, Alexander Hamilton, and many others would not only reach the pinnacles of wealth but still gamble everything they owned on a bold chance to get lots more. Stephen Girard was the same way, although in his case he never seemed to lose.

|

| First Bank |

By 1811, Girard was the wealthiest man in America. Among other things, he was the largest stockholder of the First Bank, and ran the largest shipping and merchantile empire in Philadelphia, trading extensively with France and England. From these contacts, he was able to see relationships between France and England, and between England and America, we're going to deteriorate into war. So, Girard cashed out, totally selling his overseas trading interests rather than risk blockades and confiscations. It was a shrewd move, boldly getting out before others could see what he saw. Girard was 61, his wife was permanently hospitalized, and he certainly never had to work again.

As a major stockholder in the bank, Steven Girard was well aware of the strong populist sentiment that the Government had no business running a bank. Although he did his best to preserve the bank, he could see its closure was politically inevitable with Thomas Jefferson as President of the United States, soon to be followed by his Virginia crony, James Madison. When the charter was revoked, Girard took his immense cash horde -- and bought the doomed bank with it. From the Virginians' perspective, they were going to need that money if they went to war with England; while in Girard's view they could not possibly fight a war without a bank to finance it. As matters turned out, the War of 1812 was largely financed by Girard's personal wealth, which ultimately meant that Girard bought the Government's bank with the Government's own money.

|

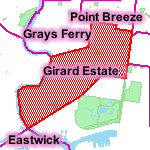

| Girard Estate Map |

Even making allowances for the fact that the troubles over the national banks were a symptom of the immature financial markets of the nation, which made passive investment difficult for those with rentier ambitions, Girard was clearly a compulsive gambler. Most compulsive gamblers are losers, Girard just happened to be a compulsive winner. His new bank was enormously successful, and as late as 1829 he purchased all of Schuylkill County for its coal discoveries, expressly directing in his will that his heirs were never to sell it. His estate still owns a large part of South Philadelphia, based on the same long foresight of a pretty old man. If you think that's easy to do, just ponder what finally happened to Robert Morris, Haym Salomon, and Alexander Hamilton.

Azilum: French Asylum on the Susquehanna

Off with their heads!, she said. They have refused my cake in preference of moldy bread, by God"

French Philadelphia

|

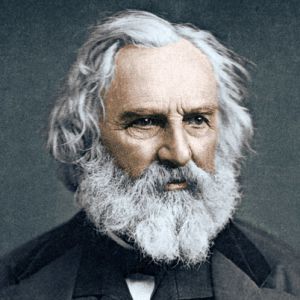

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow |

Since American relations with France are a little strained at the moment, it may not be completely welcome to hear it said that Philadelphia food is Creole. The reference is not to the several downtown French restaurants of outstanding quality, but to the two episodes when Philadelphia experienced waves of French immigration. The first of these was during the French and Indian War, when the Acadian French ("Cajun") were driven out of Nova Scotia, largely went to Louisiana and then were allowed to return. A lot of them stopped off in Philadelphia both going and coming. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow depicted, in his poem Evangeline, the tearful reunion of Evangeline and Gabriel in the hospital. And since for sixty years the Pennsylvania Hospital was the only hospital in the country, Longfellow had to put them here.

The second wave of French immigration was provoked by the guillotine in Paris, and the black revolution in French Haiti. Most people today are unaware that Talleyrand lived here, and LaRochefoucauld. The Duke of Orleans, future king of France, lived at 4th and Locust Streets, proposed to a (rich) Philadelphia lady, and was rejected by her father ("Sir, if you do not become king of France, you will be no match for her, and if you do become king, she will be no match for you.") Napoleon's brother Joseph lived at 9th and Spruce, and one of his marshals lived at 6th and Spruce. Really. Talleyrand had a deformed foot, and this somehow made him pals with Governor Morris who had a wooden leg. This friendship was part of the reason the Louisiana Purchase was possible, because they shared the favors of the same French lady, and had frequent occasion to meet. Both Franklin and Jefferson were ambassadors to France, it may be remembered, and for a while, Jefferson was quite a fan of the French Revolution, although the treatment of LaFayette by the French Revolutionaries did not exactly encourage that. The French treated Franklin like a God, but then so did Mozart and the King of England, and Franklin harbored many bitter memories of the French and Indian War all the while he was romancing the French into bankruptcy to pay for our revolution. The French refugees from Haiti brought Yellow Fever with them, and Dengue too, thus definitively terminating Philadelphia's hope of remaining the permanent capital of the nation.

It was during this Francophone period that Philadelphia cuisine acquired some characteristics which allow some food historians to call it Creole. Philadelphia Pepper Pot soup, for example, substituted tripe for terrapin. Those who know about these things say that many dishes now thought to be distinctly Philadelphian in fact had a French origin.

Elias Durand

|

| Elias Durand |

Philadelphia has a long and bumpy history with the French, more or less paralleling the British wars with them. But when the guillotine threatened aristocratic necks, Philadelphia offered a sanctuary of new world enthusiasm and sophistication. A few years after the terror, during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, Americans scorned his monomaniacal approach to government, returning to the British disdainful view of Frenchmen. In another era, Philadelphia would change its view, displaying a prominent collection of sculptures by the famous French artist, Rodin. And in today's political climate, of course, the French and their socialist leanings are akin to the devil incarnate. It can not be denied, however, the French had a major influence on Philadelphia society and culture. Elias Durand, a former member of the Academy of Natural Sciences whose portrait hangs in the Library Reading room, was a French refugee whose love of Botany greatly expanded American understanding and knowledge of plant life in North America. Somehow, that seems appropriate for an educated Frenchman. But his achievements in commerce were at least as important to his adopted city as his intellectual ones.

The youngest of fourteen children, Durand was born in Mayenne, France in 1794. A passionate chemistry student, he studied pharmaceuticals in school where he was also introduced to the subjects of natural history, mineralogy, geology, and entomology. His rich education in both Mayenne and Paris expanded his interest in chemistry to include the interplay between the hard sciences and the natural world. In 1812, after studying in Paris, Durand joined Napoleon's army, where he served as a medic and "Pharmacien," overseeing the opening of hospitals and the care of wounded soldiers. Even while serving in one of France's most historic wars, Durand remained passionate about the world of plants, by some accounts even collecting plants during the notoriously bloody Battle of Leipzig.

When Napoleon's luck turned bad, Durand focused his attention back to chemistry. In 1814 he left the army and moved to Nantes, where he worked briefly as an apothecary, as well as a lecturer on Medicinal plants in the regional Academy. Durand would remain a teacher throughout his life, instilling those around him with a fascination and passion for the Natural Sciences.

Always a patriotic Frenchman, however, Durand rejoined Napoleon's forces during the general's final hurrah, the "100 days." After Napoleon sustained his ultimate defeat at the battle of Waterloo, Durand retired from military duties and focused once again on the study of pharmaceuticals. His earlier connections to Napoleon, however, led to some uncomfortable clampdowns on the young man's freedom; Durand left the country in disgust in 1816 at being forced to report himself to the police every morning. He sailed to New York in pursuit of a life free from politics and dedicated to his passions of botany and chemistry.

Durand was quickly welcomed into the homes of other French ex-patriots living in Boston and soon met ambitious and science-oriented men who encouraged the young chemist to stay in the country. Hearing there might be work with Dr. Gerard Troost, the first president of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Durand traveled by foot to the mid-Atlantic region. This adventure brought him into contact with local Native Americans, whom he found friendly, as well as local native colonists, whom he found less so.

After a long and arduous journey down the East Coast, Durand finally arrived in Baltimore, only to learn that Troost was not in need of an employee. He was, however, desperate for a companion, and after spending several weeks in Troost's company, Durand left to find work in Baltimore with increased enthusiasm for Botany and in particular native species of North America.

In Baltimore, Durand found work with Mr. Ducatel as a pharmacist and apothecary. He quickly settled into the business, gaining experience in the field and eventually marrying Mr. Ducatel's daughter. But after five years in Baltimore, with both his wife and his father-in-law had passed away, Durand left Baltimore to search for new opportunities.

|

| Former Pharmacy at 6th and Chestnut |

He found them in Philadelphia. Perhaps because of the city's burgeoning field of Natural History or its emerging reputation as a medical town, Durand became committed to forging a career in Philadelphia. With the hope of opening a pharmacy in the finely decorated "European Style," Durand returned to France in 1825 to collect materials for this undertaking. Upon his arrival back to town, he set up a shop at 6th and Chestnut streets. His store quickly became world renown for its unique and finely produced medicinal pharmaceuticals, unique in its access to both old world and new world innovations.

Philadelphia proved to be a good move for the young Frenchman; in the next few years he married Marie Antoinette Berauld, a refugee from the St. Domingo Insurrection, and achieved election to the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy.

After his wife died in 1851, Durand gave up business to pursue the study of Botany. He was elected to the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1852, and during his membership published numerous articles and books on the botanical findings of expeditions to the American West and the Arctic. Durand also contributed to the study of Botany through the publication of several biographies about the lives of botanists Thomas Nuttall and Andre Michaux, the famous arborist. Durand's deep and lifelong appreciation for the study of Botany helped bolster the Academy's resources during his membership.

As Durand grew older, his French roots called him back to the homeland; in 1860 he returned to France, and finding the collection of North American specimens lacking in the Jardin des Plantes de Paris, determined to expand the collection himself. He returned to Philadelphia and spent the remainder of his life developing his collection of North American specimens with the help of his son. Eight years later, in 1968, Durand shipped his collection of 10, 000 specie herbarium to Paris where it was arranged in a special gallery named after him, the Herbia Durand. Much of Durand's remaining collection, however, was left to the Academy after his death.

After this long, varied and successful career in the world of Natural Science, Elias Durand died in his home on 9th and Broad Streets (sic) in 1873 at the age of 80. He had contributed greatly to the fields of Botany and helped to establish Philadelphia's respected reputation in the world of medicine. Although a Frenchman at heart, Durand remains a feather in Philadelphia's cap and an important face at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Philadelphia in 1876: The Centennial

|

| The Centennial Exhibition |

The Centennial Exhibition could easily claim to be the most transforming event that ever happened to our town. It represented the hundredth year of our independence, although 1887 would be the hundredth anniversary of our nation, and anyway, the Declaration of Independence was just sort of a hook to hang the exhibition on. Opened in the spring with a speech by the Civil War victor, Ulysses S. Grant, it was also closed in the fall with another speech by him. The planning, design, and atmosphere of the whole thing was triumphalism -- the world will never be the same because this country has arrived. The exhibition introduced to an awe-struck world, the electric light bulb, the typewriter, and the telephone. We've won the Civil War, and this is how we won it. It's too bad of course that we had to tousle up the South that way, but look at how great it is going to be to participate in the Colossus of Tomorrow.

|

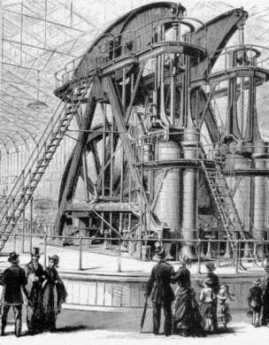

| Corliss Steam Engine. |

The civilized world competed with each other to display their things of pride in national pavilions. And next to them was even bigger pavilions by the States, with even more matters of pride to display. The main exhibition hall covered twenty-one acres. The future was here, and it was machinery. Machinery Hall was filled with thousands of machines of one sort or another, and wonder of wonders, they were all driven by one operator controlling a single huge engine, the Corliss Steam Engine. The Age of Artisans and Craftsmen was over. We had entered the world of Industrialism.

It was intended that the rest of the world should take notice of America, and of course of America's bumper City. Less noticed was that Philadelphia woke up to the rest of the world. Over eight million people attended the exhibition, most of them Americans. A great many Philadelphians spent a whole week poring over the exhibits, and some even spent a whole month doing it. Just as Japan got the jolt of its life when Commodore Peary showed them just how far-out-of-it-all they were, Philadelphia got the same jolt from the European exhibitors at the Centennial. We were showing off, but we were learning.

Cecilia Beaux, Portraitist of the Grand Manner

|

| Cecilia Beaux |

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) was certainly the most famous woman portraitist of her time. She had the misfortune of being a contemporary of Mary Cassatt, who enjoyed the reputation of the finest woman Impressionist at a time when the Art world disdained traditional painting techniques in an Impressionist stampede. So, although these two temperamental artists might never have been chums, much of their famous rivalry was probably invented for them by art world politicians.

In time, the assessment will emerge that these two well-born Philadelphia ladies were each the world's female leaders of two competing schools of art. Comparisons of the two will also have to be filtered through the fact that Cassatt was a rebel who spent most of her life in Paris, while Beaux was a prominent faculty member of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for twenty years. Strikingly beautiful herself, she was gifted, elegant and fiercely ambitious. Meow.

|

Once Beaux had established a reputation as a portrait painter, she shrewdly began to select her subjects. She wanted famous men (Henry James, for example) and beautiful women subjects. She made the mistake of turning down her niece, Catherine Drinker Bowen, because she didn't have the right kind of cheekbones. She learned, of course, that it's unwise to tell a famous author she is ugly.

|

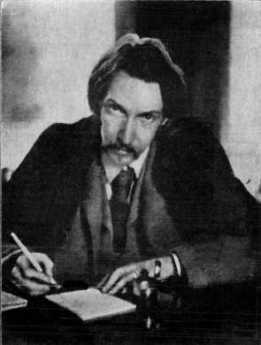

| Robert Louis Stevenson |

Cecilia Beaux's main competitor in the portrait game was John Singer Sargent, who was if anything a better painter but a stammering social dud. Sargent remained a life long bachelor, Beaux a spinster. Her mother had died in childbirth, and it seems likely that terror of pregnancy was an important part of her personality, during the pre-antibiotic era when such fear was fairly justified. As a young woman, she turned down proposals by the dozen, and in maturity, she had a succession of apparently platonic but intense relationships with handsome men twenty years her junior. During the late Victorian era, this sort of thing was not rare, although medical advances have apparently largely eliminated it. To return to her competition with Sargent, the personality differences probably account for his haunting portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, while Beaux is notable for arresting portraits of rich, famous and beautiful women, and an equal number of well-dressed, handsome men.

Mary Cassatt

|

|

The most famous Philadelphia Cassat shows a mother driving an open carriage with small daughter beside her, and her brother on the back seat. |

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844-1926) is variously proclaimed as the greatest woman artist ever, and America's greatest impressionist painter of either sex. She is thus, from a Philadelphia perspective, the greatest Philadelphia woman artist. Mary was, in truth, born in Pittsburgh spent most of her artistic career in Paris, and relatively few of her numerous pictures are to be found in Philadelphia. But she spent four years training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, her family moved to Philadelphia, and what is most important of all, her brother Alexander was president of the Pennsylvania Railroad at a time when such a position was nearly the same as being King.

|

|

Alexander Cassatt President of the Pennsylvania Railroad |

Almost all of her many paintings used members of her family as models, and almost invariably the paintings portray women or young girls. If there is a male in the picture (and there are a few), you have to recheck the label to be sure it is a Cassatt. This bias raises questions about her private life, which she would certainly have regarded as no one's business. She was the long-term competitor of a slightly less famous Philadelphian Paris artistic exile, Cecili a Beaux, and she was very active in the suffragette movement. On the other hand, she had a forty-year relationship with Degas, with whom she was professionally very close, as well as personally.

Mary Cassatt was a classmate at the Pennsylvania Academy of Thomas Eakins, but they did not get along. The master anatomist and the greatest woman impressionist were certainly hampered by professional disagreement; apparently they both took it personally.

Beaumarchais: A Playwright Brings France into the American Revolution

|

| Pierre Augustin Beaumarchais |

Pierre Augustin Beaumarchais, the son of an 18th Century French watchmaker, was born Protestant in a Catholic country. While possibly inclined by this circumstance to be a free thinker, his unusual artfulness was more likely inborn. After revolutionizing watchmaking before he reached the age of twenty, with an escapement mechanism for small portable watches, he rose to social attention when the Royal Watchmaker claimed the invention was his own, and Beaumarchais sued him. Thus gaining Louis XV's notice, Beaumarchais became Royal Watchmaker himself. He was soon giving harp lessons to the ladies of the court, writing plays like The Barber of Seville, and engaging in business schemes with wealthy investors. His career as a court favorite lasted sixteen years, first bringing him considerable wealth, but then sudden ruination by a lurid lawsuit which cost him his fortune. In brief, Beaumarchais had tried to bribe a French judge with less money than his opponent offered, and so spent a few months in prison. After concluding a long, public battle through the appeals courts, he sought a more political role with the new young King, Louis XVI. He was sent to London to pay off a former French Agent, Chevalier D'Eon, who was blackmailing the French government. D'Eon's social connection to John Wilkes, the outspoken critic of the British King, sparked Beaumarchais' initial interest in Whig politics and the American rebellion.

|

| John Wilkes |

When he arrived in England Beaumarchais found British politics in turmoil; John Wilkes headed a whiggish opposition movement denouncing Royal authority and hosting gatherings of the like-minded, some of which Beaumarchais attended. Fueling these domestic British flames of liberal reform was the recent and increasingly serious rebellion on the other side of the Atlantic. As Beaumarchais spent more time in England discussing the rebellion with Virginian Arthur Lee (who highly exaggerated its strength), he became increasingly convinced it would be a good strategy for France to help the colonists. For all the trouble Arthur Lee ended up causing, he can fairly claim credit for enlisting Beaumarchais to French support for the American cause.

|

| Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes |

Beaumarchais reported his findings to Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, the foreign minister of France. He urged the French government to support the American rebellion, consistently taking the line of French self-interest; after suffering a humiliating defeat in the Seven Year War, France might now undermine England's growing regional power by helping the colonists loosen their affiliation to the rising island empire.

When the young and hesitant Louis XVI finally agreed to take Beaumarchais' advice, it was still unclear whether the American rebellion was a serious movement. The French monarchy was not ready to unsettle its already shaky relationship with England by coming out in public support of untested rebels. To preserve the appearance of neutrality, the French Government loaned Beaumarchais one million lives in June 1776 to start a private trading firm, the Rodriguez Portales Company. This new firm would buy old French military supplies from the French government, then re-sell those supplies to the Americans with return payment of American products, primarily tobacco. Beaumarchais was therefore expected to run a completely self-sustaining operation, free from association with the French government. Rogue and adventurer that he was, Beaumarchais took on this risky challenge with enthusiasm, working tirelessly in France and around Europe to provide the Americans with ammunition, military supplies, and food. His efforts did not go undetected, however. England's ambassador to France, Lord Stormont, grew suspicious of Beaumarchais' frequent trips across the channel and notified the French government of his displeasure. But Beaumarchais simply ignored these protestations.

Matching Beaumarchais' work in establishing Rodrigez and Hortalez, the American Congress sent a covert representative to nurture French support. Silas Deane, sent to France under the disguise of a colonial merchant in July 1776, learned of Beaumarchais' plan to support the American army and at first, the two became fast friends. Unfortunately, this friendship sparked the jealousies of Colonists and Frenchmen alike. Arthur Lee became a particularly vicious opponent of the Beaumarchais/Deane pair, resenting Silas Deane for having been chosen over him as a diplomat to the French, and suspecting Beaumarchais of money laundering. Even when he was later sent in company with Benjamin Franklin to continue negotiations with France, Lee remained suspicious of Deane and Beaumarchais' collaboration. The American mission to France during this period remains famous for strife and factionalism, which was as much a free for all as two-sided animosity. Personal ambition and cultural differences complicated these relationships; no one eventually suffered more because of it than Beaumarchais and Deane.

While Deane negotiated with Beaumarchais, Arthur Lee corresponded with Congress to undermine both Beaumarchais and Silas Deane. Lee was highly suspicious of both men, accusing them of using the privateering scheme for their own profit. The result was a split in Congress between those who supported Lee and those who supported Deane's work with Beaumarchais. The first congress was full of alliances, tempers and faulty information that led to frequent, if not constant, conflict. The Lee brothers were particularly vocal opponents of an alliance with France, and this opposition by a prominent family within the Continental Congress kept French and American relations strained and hesitant.

The first shipment to the colonies by the Rodrigez and Hortalez Company carrying nearly 25,000 pounds of ammunition, was a shaky and often blind operation. Continental Congress never received news of Deane's plans (and request for ships) and remained busy working away at a proposed Declaration of Independence, the publication of which would, with luck, ensure France's official cooperation. Deane was forced to make crucial shipment decisions without the support or approval of Congress. Adding to this instability, the ships were discovered by Lord Stormont right before the first shipment left for the colonies, and the English Ambassador to France quickly protested their sailing to the French government. Vergennes, eager to keep smooth relations with England, particularly in view of the seeming failure of the American cause at that time, officially banned their sailing off the French coast. Fortunately for the Americans, Beaumarchais sent the supplies anyway, which were greeted warmly by colonists in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in early 1777. These supplies helped the colonists win the Battle of Saratoga, the success of which finally convinced the French to emerge in full support of the American Revolution. Beaumarchais continued to supply the Colonists despite England's protests, but privateering increased the threat of war between England and France.

|

| Barber of Seville |

By September 1777, Beaumarchais had shipped 5 million lives worth of supplies to America without repayment. By 1778 his firm had accrued so much debt that by the end of the war it was in complete ruin. The French government was unwilling to acknowledge its support for Beaumarchais before or after the war, and Silas Deane's entreaties were, unfortunately, not enough to convince Congress that the American colonies owed Beaumarchais for his generous work. Beaumarchais continued his requests for compensation after the war, and Congress continually refused or ignored these requests. Thirty-six years after his death, his heirs were paid back a small fraction of the original debt. Forced to travel to Congress to fight their ancestor's case, his descendants were awarded 800,000 lives of the several million owed. In effect, Beaumarchais nearly single-handedly supplied the American Revolution with arms receiving very little in return except his financial ruin.

It is surprising that a man with so much talent and character should have died in near obscurity; yet Beaumarchais' plays, not his political maneuverings, are what have survived today as part of the standard repertory. When his wildly successful The Barber of Seville premiered in 1775, Beaumarchais was already a well-known playwright and champion of the down-trodden common man. Perhaps he was too great for his own time; The Barber proved more popular when adapted into a libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte and then later into an opera by Gioachino Rossini in 1814. An independent mind and flamboyant character immortalized his art, but the same characteristics may have brought him, and France, to political and financial ruin.

Citizen Genet

|

| America and France signed a treaty of alliance |

In 1788, America and France signed a treaty of alliance, which clearly rescued the American Revolution from disaster. We owed France "big time". After the French King was executed, Great Britain, Spain and other monarchies declared war on France, and the French expected our help. However, eight years of war had left the United States in disorder, and President George Washington was determined to keep us out of any entanglements which slowed our recovery. This probably would have been true in any circumstances, but in addition, the U.S.-French alliance had deteriorated even at the Treaty of Paris. In diplomatic circles, the defining quip was that we signed a separate peace with Britain, "Betraying the French before the French had a chance to betray us." We were certainly not going to ally ourselves with the British after eight years of war, so the only possible stance was the one Washington adopted -- neutrality. No foreign entanglements.

|

| Edmond-Charles Genet |

The French government at that moment was in the hands of the Girondists who were plenty radical, but positively meek compared with the Jacobins who soon took control and employed the guillotine routinely. The Girondists exercised particularly poor judgment in sending Edmond-Charles Genet to the United States to enlist help in their war with England and Spain, because he had just been declared persona non grata and expelled by Catherine the Great from the Russian embassy, with the notation that he was "not only superfluous but intolerable." He was only 31 years old, generally regarded as a genius for being able to read French, English, Italian, Swedish, and German -- by the age of 12. Whatever the truth of this claim, it was instantly recognizable that he was wild and uncontrollable, without a shred of prudence.

Although it is part of the diplomatic minute that a new ambassador's first act is to present his credentials to the head of government in his new post, Genet headed instead for Charleston, SC. Probably with the idea of wasting no time getting down to business, he soon enlisted four privateers in Charleston to begin predations on the British and Spanish in the West Indies. By the time he finally got to present those credentials to George Washington, he had stirred up several commotions between us and the British, since part of his mission was to get the two of us into war with each other. Meanwhile, he quickly made himself a political threat by becoming the toast of the town in Charleston, and even after he arrived in Philadelphia. At a time when his position with Washington, Hamilton, and even Thomas Jefferson was strained, he attended a famous dinner party with Governor Thomas Mifflin in attendance, and ceremoniously cut off the head of a roast pig in guillotine fashion, ho, ho, ho. Not only was this gauche, crude and disgusting, but it was also pretty stupid. Thomas Mifflin, after all, had been the real instigator of the so-called Conway Cabal to depose George Washington from command of the Continental Army at Valley Forge, so Citizen Genet got political black marks just by going to the dinner. He was spared the indignity of expulsion by the replacement of the Girondists by the Jacobins, who promptly sent a warrant for his arrest. Since that surely meant he would be beheaded, Washington gave him sanctuary.

The British uproar was intense after the depredations of Genet's privateers using American refuge, and Washington dispatched John Jay to England to patch things up. The outcome was a treaty with the usual diplomatic mixture of goodies and concessions. In this case, the British troops who had been left behind on the American western frontier in violation of the terms of the Treaty of Paris were recalled, and payments were made for some war damages. But in return, Jay had to agree to limit American trade in the West Indies; and that inevitably caused denunciations from the growing anti-Federalist faction. Congress was eventually persuaded to ratify the Treaty but Washington paid a political price for neutrality with both the French and the British. Politicians were starting to act with characteristic intransigence. Throughout all this mess, Washington behaved with characteristic calm and reserve, but in fact, he was pretty down-hearted about it.

Under the circumstances, Genet worked the dinner circuit and married Cornelia Clinton, the daughter of the Governor of New York. After a few years, she died, and he remarried Martha Osgood. He became a gentleman farmer on a farm overlooking the Hudson River, and nothing much was heard about him for the next 40 years.

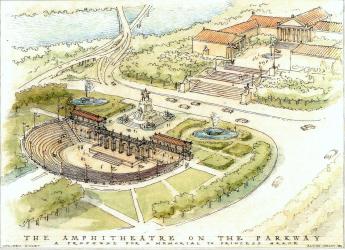

Proposal for the Parkway

|

| Alvin Holm |

Architect Alvin Holm spoke recently about an idea he had dreamed up in 1986, for an amphitheater in the Eakins Oval, right in the middle of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. At that time he envisioned it as a memorial to Grace Kelly, but Monaco wasn't interested, and the City was broke. But times change, neighborhoods change, and maybe the idea needs to be re-examined.

A bit of history needs to be refreshed. Around 1900 when the Parkway was dreamed up, Philadelphia was said by some local boosters to be the richest city in the world. That may have been a little overoptimistic, but it was nearly true enough that no one laughed loudly when it was enunciated. The Parkway was envisioned as a new departure to transform the whole city from square blocks of red-brick buildings of Georgian style, into a classical French version of grand elegance. To emphasize the new departure, it cut a diagonal from City Hall to the Art Museum, uniting these two French architectural monuments into a transformational classic boulevard. It wasn't just an imitation of Champs Elysees, it was a design by the very same architects, intended to lead the centers of many great cities of the world into modernized versions of the Roman Forum. Paris somehow managed to get away with it in time, but the 1929 crash stopped Philadelphia's dreams dead in their tracks, and the city just didn't recover.

Consequently, vast stretches of North and West Philadelphia were abandoned, then transformed into slums as poor people sought cheap housing. If you just look at Baltimore and Newark, you can easily see how sudden reversals can destroy a city completely. Philadelphia retreated into Center City, surrounded by an inner ring of slums, which were in turn surrounded by a ring of newer suburbs. The automobile hastened the flight to the suburbs, while the business district retreated to the inner core of Center City. In order to protect the Shining City on a Hill from being completely disrupted, informal barriers were sought, and the Parkway became one of them. They weren't walled moats, but they served the same purpose. Therefore, during the long decades of limping along, occasional cries of, "Why don't we make the Parkway into a grand boulevard?" had a silent, sullen answer. We weren't really sure it was a good idea. It didn't fit within our revised circumstances.

|

| The Amphitheatre on the Parkway |

But the City is now getting back on its feet, as anyone who has noticed the astonishing restaurant revival of Fairmount Avenue, or of Old Towne, or Society Hill, and the rebuilt "Chinese Wall" leading to and from the old Broad Street Pennsylvania Railroad station, can easily see. The Independence Mall and the University of Pennsylvania areas were largely built with Federal Money, but no matter, the transformation is still evident, the tide has turned. So Alvin Holm got out his drawings about premature dreams we couldn't afford, and asked, "Is it time?"

The unfinished Ben Franklin Parkway has cut its path, willy-nilly, through the neighborhoods, the trees have had time to grow, the museums time to migrate. The childless couples of the metropolitan area were coming back in town to enjoy the restaurant revolution and the theater revolution. Alvin Holm was getting a little older but not less energetic. He remembered that at the foot of the Art Museum was a statue of George Washington on a horse, and behind our First President was a big expanse of empty land. To build an amphitheater only took bulldozers, and could seat a thousand people. If you were as lucky as the ancient Greeks, and possibly if you built in precisely the same way, a speaker in the center could be heard -- without artificial amplification -- if he whispered, by everyone in the amphitheater audience. If you do use electronics, there's plenty of space in back of General Washington for a dignitary to give a speech on a raised platform, and there's enough empty audience space in a wider sweep, for fifty thousand people to congregate and listen. To him, or to a rock band, or whatnot. There aren't very many places left on earth in the center of a big city, where a single person can stand against a magnificent classical background, and be heard by fifty thousand chanting, hollering true believers. All of this could be accomplished by essentially digging a hole in the ground and closing off the area to traffic. But oh, yes, it takes one more thing. You have to want to do it. So let's consider for a moment who else covers the neighborhood, waiting for the right time to make a move.

|

| Amphitheater Sketch |

Instead of regarding Fairmount Hill as just a big obstacle to automobiles trying to get home, let's just see what some others are thinking. For example, the people who run Drexel University are seriously talking about buying the air rights above the railroad marshaling yards on the west bank of the Schuylkill, and putting up a major business district and residential complex. They are thinking mainly of reviving West Philadelphia, and that's fine, but another bridge at that spot is badly needed to divert traffic around the present choke point on the Schuylkill Expressway, and that's also fine. Put some paths down to the river from the Art Museum to meet a new pathway to the Drexel development, as well as the recreational area along the river, and you could really have something pretty nice for the commuters who would otherwise begrudge the cost of digging an amphitheater hole in back of G. Washington.

Looking to the north of the Art Museum, there's a second small mountain with Kelly Drive between the two. At one time, both hills had reservoirs on top. The Art Museum demolished one reservoir, but the other reservoir is still there. It's a fifty-acre lake surrounded by dense forest; but from the inside look back over the top of the trees and you can see skyscrapers, almost right next to you. It's been adopted by migratory birds as part of the Atlantic flyway, and you would just be amazed at the hawks and ducks and all manner of other little black jobs that fly around and get recorded by bird watchers. The lake is full of fish, probably originally dropped by passing birds. The Audubon Society has a fundraising project going on, right now, to build a visitors' center in the forest, in conjunction with Outward Bound, the rock climbers group. Go to the left and you are overlooking the races at Boathouse Row, turn in the other direction to see Girard College, the hospital complex, and the further north you get to Temple University.

And one more thing. The old B&O Railroad once snaked along the Schuylkill and turned right around the (now) Art Museum, through tunnels over to Spring Garden Street, and down to Reading Terminal. Just what to do with this ditch running through the center of town unnoticed, is beyond my scope. Let someone else have a chance at being a visionary, but it must be remembered that New York City recently had a similar relic on its hands, and made something pretty nice out of the West Side of their town.

All of this potential even has the danger that projects will collide with each other, so it would sound like a nice idea for some Foundation to put together a planning board, to fit it all together without getting mixed up in politics, or squabbling over who will run things. But even that fuss would be a novelty, a nice thing to have for a while.

Barnes Foundation -- Drawing a New Moral

|

| Andrew Stewart |

Andrew Stewart, the Public Relations Director of the Barnes Foundation, and for thirteen years a member of its Board of Directors, recently addressed the Right Angle Club. He gave a new slant to the quarrelsome saga of Dr. Barnes' will, offering the point of view in favor of moving the paintings to the Parkway. It's useful to hear the legal and historical background because about all we hear are criticisms, balanced by joy at having the famous paintings where we can see them.

Essentially, the will declared a wish for the School and Museum to follow the original indenture. After the passage of time, the old board members died off, and the new board members found the Indenture to be out of date, like specifying the purchase of railroad bonds. Delivered in a charming Scottish brogue, the argument was fairly convincing. But it stimulated in me an entirely different moral from the eternal dispute between the right of a man to have respect paid to his expressed wishes for his own property, versus the self-defeating quality of the same restrictions with the passage of time.

|

| Barnes Foundation |

Barnes was born in Kensington, and had a hard life as the son of a Civil War veteran who lost an arm in the war, and had a dismal time making a living as a butcher. Barnes was his fighting-spirit son, who worked his way through medical school. It was Jefferson Medical College, where I was on the faculty for decades. While it is true his patent medicine gave a permanently sickening color to the children who were treated for sinusitis, it is also true that in the form of eyedrops it prevented the transmission of syphilis to millions of newborn children. In that view, it was a real scientific contribution, although the medical profession continues to take a dim view of doctors advertising their wares. Although he was himself a failed artist, Barnes was a highly successful collector of (then) modern art and started a school with John Dewey to teach art appreciation to poor people. One by one, the local universities snubbed his wishes for an art appreciation school, and the local Philadelphia museums were pretty sniffy about his favorite artists.

In fairness to them, Barnes was probably pretty pushy in his demands. Unfavorable local reception to an exhibition which had received rave applause in Paris, convinced Barnes he was right and they were wrong. After this, Barnes developed a lasting hatred of Philadelphia and all its stuffy ways; he definitely didn't want his own impressionist art to be in Philadelphia, which would never appreciate it. While Philadelphia finally woke up to the value of Impressionist painting, Barnes never relented while he was alive. I hope I give a fair portrayal of the argument except for the politics and the legalities, that I know very little about.

But hearing the arguments, I see an entirely different moral to the saga. Ever since the inflation of the 1930s, fine art has appreciated in value, faster than the endowments to maintain the art. (That's probably a useful tip to investors, too.) It's fairly standard for a wealthy person to donate his art collection, plus a sum of money to endow the maintenance of the art. Most of the time, the size of the endowment is carefully calculated to grow at least as fast as the value of the paintings, because you have to ensure them, and pay for increased security, and increasing attendance. With the new trend toward inflation of at least 2% a year, the old premises don't work anymore, and the endowment eventually runs out. At that point, it runs into restrictions which -- to be perfectly blunt -- were created to prevent the trustees from pilfering the museum. A museum may not sell its art to pay for administrative expenses.

Consequently, The Barnes ran into a situation where it had billions of dollars worth of paintings in the basement, which it could not sell, and could not even hang in the museum because of Barnes' specifications for what went on the walls. This situation isn't going to change, because a dollar in 1913, when the Federal Reserve was created, is now scarcely worth more than a penny. And the present Fed is committed to 2% inflation, forever.

So, how about this: let the lawyers who write wills, and the Orphan's Court which administers them, insist that the art collection be divided into two parts. One would be the permanent collection, just as at present, and the other would be eligible for sale in the judgment of the Orphan's Court.

GIC in Paris

|

||

| GIC logo |

Delegation Agenda

Sunday, May 11th:

6:30pm -7:00pm: Arrival and cocktails

Location: Aux Anysetiers du Roy, 61, rue St. Louis en L'Isle Metro: Sully Morland or Pont Marie

7:00pm: Dinner will be served; Registration and pre-payment was required for this event.

Monday, May 12th:

9:00am - 9:15am: Arrival and registration. A light breakfast will be provided.

Location: Bistro de la Muette, 10, Chaussee de la Muette 75016 Paris Metro: Muette

9:15 am - 10:00 am: Presentation by Michael Kennedy, Head of the General Economic Assessment Division, Department of Economics, OECD, on Outlook by the OECD.

10:15am - 11:30am: Round-table discussion directed by John Silvia, Chief Economist, Wachovia Bank, including Paul Thomas, Chief Economist, Intel, Tom O'Connell, Assistant Director-General of Central Bank of Ireland, Sandra Pianalto, President of Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank, Mario Baldassarri, Senator, The Republic of Italy, and David Kotok, CIO, Cumberland Advisors. Each participant will introduce a topic of concern to the group with GIC delegates acting as discussants. Chatham House Rule will apply.

12:15pm - 1:30pm: Lunch at Bistro de la Muette, sponsored by Cumberland Advisors and Wachovia.

1:30pm-7:00pm Free Time

7:00pm - 7:30pm: Cocktails and Hors d'oeuvres.

Location: Cercle de L'Union Interalliee, No. 33 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honor' 75008 Paris Metro: Concorde or Madeleine, 5-10 minute walks

7:30pm: Private dinner with Paolo Garonna, Deputy Executive Secretary United Nations

Economic Commission for Europe and sponsored by Cohen and Company. Dress code for the club requires a jacket and tie, no blue jeans or tennis shoes please.

Tuesday, May 13th:

8:45am-1:10pm: GIC & CEPII Conference "Monetary Policy and the Exchange Rate: The Euro and the Dollar"

Location: Maison des Arts et M'tiers, 9 bis Avenue d'I'na, 75116 Paris, Metro: Iena

Full Program will be distributed at the event. Speakers and moderators include:

William Dunkelberg, Chairman, Global Interdependence Center

Agn's B'nassy-Qu'r', Director, CEPII

Lionel Fontagn', CEPII

David Kotok, Chief Investment Officer, Cumberland Advisors

David Woo, Head of Foreign Exchange Strategy, Barclays Capital

Manuel Balmaseda, Chief Economist, CEMEX

Denis Verret, Senior Vice Preside of Operations and Sales, EADS

William Clark, Director, New Jersey Division of Investments

Laurence Boone, Chief French Economist, Barclays Capital

Sandra Pianalto, President, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

Christian Noyer, Governor, Banque de France

1:10 pm ' 2:30 pm: Luncheon for conference attendees at the Maison des Arts et Metiers sponsored by Barclay's Capital