Related Topics

Right Angle Club: 2015

The tenth year of this annal, the ninety-third for the club. Because its author spent much of the past year on health economics, a summary of this topic takes up a third of this volume. The 1980 book now sells on Amazon for three times its original price, so be warned.

Right Angle Club 2017

Dick Palmer and Bill Dorsey died this year. We will miss them.

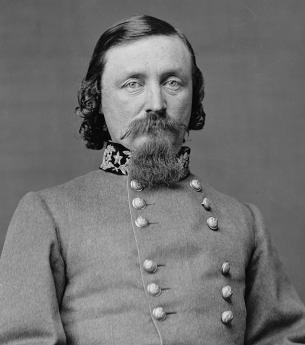

Pickett's Charge

|

| General George Pickett |

If you want to baffle a Philadelphian, just stop him and ask who defeated Pickett's Charge at the battle of Gettysburg. Like the Charge of the Light Brigade, everybody knows who the losers were, but nobody seems to know who won the battle. After all, history is usually written by the victor.

Well, in fact, the battle was won by 13,000 Union troops stationed at the Bloody Angle, only two soldiers deep behind a stone wall, to defend against 60,000 Confederate troops who had been concentrated by Pickett to converge on that point of defense. The whole Union army of about 60,000 men had been strung out along a farmland ridge, uncertain at what point Pickett would concentrate. At a little copse of trees at the angle of two stone walls, were three Philadelphia brigades, composed of Philadelphia blueblood officers and soldier volunteers drawn from Irish volunteer firemen, recruited by members of the Union League of Philadelphia. These Philadelphians, both officers, and men were to suffer 50% mortality in an hour of fighting. At one point they started to break and run when 150 confederate cannon were concentrated on their position, then rallied and held their ground when it was the Confederate turn to break and run for home.

|

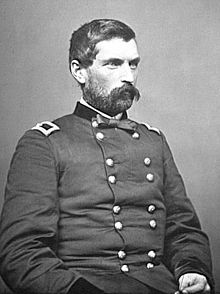

| General John Oliver Gibbon |

Although General John Gibbon was the highest ranking Philadelphian in charge, and Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb was a New Yorker who had been in command of the three brigades for only one day, winning the Congressional Medal of Honor, the real hero was Lieutenant Frank Haskell. Seeing the Union defenders starting to break, Haskell rode his white horse outside the wall ahead of his troops and suddenly ordered them to turn and fire at the hesitating Union troops. The shock of this maneuver stopped the retreat, turned the troops to face Pickett's onrushing men, and routed the Southern advance after Confederate General Armistead vaulted the wall and started to attack the defenders in hand to hand combat. A member named Haskell was in the audience when Author Bruce Mowday told this story to the Right Angle Club, but Robert Haskell never uttered a word.

|

| Bruce Mowday |

Since this incident, I have repeated the story to dozens of Philadelphians, and not one was even faintly aware of it. It reminded me of Digby Baltzell's book Boston Puritans and Philadelphia Quakers , which expresses Baltzell's opinion that Quaker reticence is the source of Philadelphia's academic and political decline. My own opinion takes a different view of the distinctiveness of Philadelphia modesty, which was contrasted with New England by John Adams' remark that "In Boston, every goose is a swan."

When you run your eye down the list of Philadelphia Union officers who fought in this crucial battle, there is only one recognizably Quaker name from a city which even at the time of the Civil War was still Quaker-dominated. Quakers had been urged by the London Yearly Meeting to withdraw from the war tax issues of the French and Indian, and Revolutionary Wars, but a great many Quakers had fought against the British, anyway. By the time of the Civil War, however, the antiwar Quaker position had considerably strengthened. I can still remember Henry Cadbury reciting the position of his mother, a satire of the Battle Hymn of the Republic: "He died to make men holy, we will kill to make men free." The Civil War had greatly strengthened antiwar sympathies in the North, especially in Quaker Philadelphia.

|

| Revolutionary War |

Consequently, when the spoils of war were handed out, public opinion demanded that the heroes of Gettysburg be rewarded, without drawing any openly negative opinions about those who declined to serve. After all, the Quakers had initiated and led the battle to free the slaves and shared a certain amount of wide-spread sympathy with the idea that the Southern states were entitled to secede if they wanted to. And Quakers at the time retained considerable wealth and the power to defend themselves, if attacked, not to mention wide-spread ambivalence about the War. So, there was no great effort to persecute Quakers, but the idea of sharing the spoils of war with them was just a little too much. Six hundred thousand soldiers had been killed in that war, and although Gettysburg contributed 51,000 of them, it was far from being the only bloody battle. It is my suspicion the constant decline of Quaker influence in Philadelphia since the Civil War, can largely be traced to unpleasant echoes of this more or less inevitable response to a postwar commonplace.

|

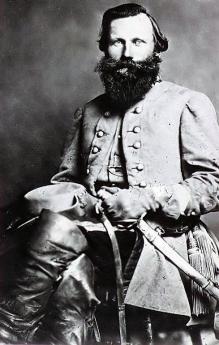

| General JEB Stuart |

It is unfair to bring up the subject of the battle at Gettysburg, without mentioning three other factors which historians cite as causes of the defeat of Generals Lee and Pickett. In the first place, the rather inferior Confederate artillery consistently overshot the target of the front line of Union troops and fell harmlessly in their rear. Lots of noise, not much damage. It is also true Confederate General JEB Stuart was planned to attack the Union lines from the rear, but was delayed by attacks of troops under the command of, might you know it, General Custer. And finally, as Pickett himself remarked, "The Union Army probably had something to do with it."

REFERENCES

| Pickett's Charge: The Untold Story. Author: Bruce E. Mowday ISBN:978-1-56980-4 | Amazon |

Originally published: Friday, June 19, 2015; most-recently modified: Friday, May 31, 2019