0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Chapter Eight: Articles of Confederation. Would They Suffice? 1777-1781

Articles of Confederation: Flaws

DURING the twenty-five years (1776-1801) government was in Philadelphia, Americans who had rebelled against tight royal rule uncovered many defects in its opposite -- a loose association of states. Loose associations only preserve fairness by operating with unanimous consent, which is, of course, unfair to a thwarted majority, unless a dissenting minority thwarts itself as a gesture of kindness. The Founding Fathers ultimately devised a formula of weakening power by dividing it into layers -- national, state, county, municipal -- and seeking to confine minority dissent to the weakest political unit. Persuasion and peer pressure were given time to work up the ladder of appeal to a wider, more powerful body of citizens. Bottom upward by choice; top-down only in desperation. Furthermore, persuasion first, force as last resort. An implicit third safety valve emerged: if a good idea is smothered by a local concentration of bigotry, appealing to a wider population includes being heard by more viewpoints. No one claims to have authored this whole prescription or foreseen its hidden benefits; it apparently evolved by trial and error. There was another latent discovery for America's sparse population in a hostile wilderness: maintaining harmony was more essential than efficiency. It would be hard to consolidate more Quakerly concepts of governance in one document. Not exactly assembled, it emerged and was admired. The local Quaker merchants were living proof that harmony made riches for anyone, while force only works against weaker people. George Washington the cavalier general came to Philadelphia and gave it a softly Virginian twist, over and over: Honesty is the best policy. It seems to have originated in one of Aesop's Fables.

It is not necessary that the [Constitution] should be perfect; it is sufficient that [the Articles of Confederation are] more imperfect.

|

| James Madison |

Recently examined documentation reveals James Madison, the main theoretician of the closed-door Constitutional Convention, to have been severely contemptuous of state legislatures at this time in his life, and rather severely defeated by John Dickinson in a political quarrel in mid-convention about the powers of small states. From this fragile evidence emerges the idea that in balancing the powers of state and national governments in the "federal" system, it may have been someone else's idea that the greater freedom to move out of an offending state into a more favorable one, would appreciably restrain state legislative abuses. Even with this feature built into the system with the national government to enforce it, Madison is said to have been in a state of depression that the Convention refused to agree to his idea of giving Congress veto power over state laws. It took some time for improved transportation to strengthen this competition between states, but it may not be an accident that Delaware now leads the way in responding to the implicit opportunity.

Philosophy and history are different. The Framers gradually acknowledged a patched charter of tribal allegiance was insufficient and thus adjusted to the idea of a central government. They tweaked a decentralized model of governance to get the states out of the road, without antagonizing them so much they would not ratify it. Although it is commonplace to say the Articles of Confederation were a weak failure, the Articles did reflect American attitudes at the beginning of our formative period. The Constitution would not have been acceptable if the Articles of Confederation had not first been given a trial. By the end of the 1787 Philadelphia negotiation, the nature of the final proposal was to define a few absolutely minimum powers for a national government, identify a few other powers as destructive when in the hands of any other level of government, and leave a vast undefined area: where new and novel problems would be tried out in the states, then passed to a national level if necessary. Anticipating constant mid-course corrections was an important objective for even a minimalist Constitution, not the least of those challenges was to create ways to keep it minimalist. Simplicity itself keeps it hard to change. Starting at the bottom of the layers of government continues to this day to introduce new and unexpected problems to the "laboratory of the states" or even lower, working upward only as proven necessary, or spread nationally only after the solution is highly successful. It is a legacy of slavery, the Civil War, and direct election of Senators (Amendment XVII) that many Americans still fail to welcome the merits of this approach, or lack the patience to try it for their pet ideas. Considering the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution as two documents with continuous goals, we got it right, the second time.

And we got it right in the environment of Eighteenth-century Quaker Philadelphia, where a tolerant examination of new ideas was more venerated than in any other place in the civilized world. With a combination of wisdom and impasse, minor issues were left to the future. It is true this sometimes creates problems of neglect. But it makes it possible to define those few issues which must never change. An unexpected virtue of minimalism surfaced eighty years later: many men understood it well enough to die for it.

|

|

Edwin Corwin's "John Marshall and the Constitution" |

Much has been written about the separation and balance of powers between the three branches of the federal government. However, the real balance of power in the Constitution in 1787 was vertical, between the central government and the constituent states. Balancing power horizontally, within the central government's branches, is a way of preventing one side of this other argument from tilting the state/federal balance in its own favor, or slowing down the effect of any victories by one side. In other words, it preserved citizen liberty to choose. From this continuing two-dimensional struggle emerges the explanation for filibusters, the seniority system, the confirmation process for Supreme Court and Cabinet appointments. It also calls into question the Seventeenth Amendment, where the state legislatures lost the power to appoint U.S. Senators. In 1786 the states had all the power, in 2009 state power is much diminished; but it is not entirely gone by any means. It is true the cry for states rights, essentially an appeal to the Deity for Justice is futile. If states are to wrest power back from the federal government, it will be by the adroit exercise of powers buried within the balanced powers of the federal branches, but it can succeed if the public ever wants it to succeed. The Framers seem to have overlooked the possibility that federal power could someday outgrow its blood supply, simply growing too big to manage. It is also true the Framers neglected the possibility of a protracted period of disagreement between two halves of the electorate. At least in these particulars, there is room for the further evolution of the Constitutional principle.

While features of the present Constitution can sometimes be linked to the correction of flaws in the Articles, one by one amendment never seemed to be quite enough. Subsequent analysis of Original Intent has often had to contend with the unspoken intent of earlier negotiators to strengthen partisan advantage in later struggles. The political battles being fought at the beginning, which except for slavery are substantially the same today, were sometimes being promoted for reasons which now seem merely quaint. Fine, everyone can agree it was complex. Still, there was a recurring uneasiness: what was the underlying flaw in the Articles? What, as they say, is the take-home point?

One widely accepted summary, probably a correct one, of what was centrally wrong with the Articles of Confederation, lies in a concise observation, which follows, from Edward S. Corwin's book John Marshall and the Constitution:

"The vital defect of the system of government provided by the soon obsolete Articles of Confederation lay in the fact that it operated not upon the individual citizens of the United States but upon the States in their corporate capacities. As a consequence, the prescribed duties of any law passed by Congress in pursuance of powers derived from the Articles of Confederation could not be enforced."

And that's how many Revolutionary Americans, possibly most of them, had wanted to have it. They were in revolt against all strong government, not just the King of England. They surely would have applauded Lord Acton's declaration that "All power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Thirteen years of near-anarchy taught them they must at least give some limited powers to a central government, but it was to be no more than absolutely necessary. For some, the Ulster Scots, in particular, even the absolutely minimum amount was still just a bit too much. In effect, these objectors wanted a democracy, not a republic.

To deconstruct Professor Corwin's analysis somewhat, the equality-driven followers of Thomas Jefferson believed the insurmountable obstacle for uniting sovereign states is that they are sovereign, and won't give it up. The merit-driven followers of Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris, and George Washington bitterly resisted; in business and in war you need the best leaders to rise to power. The function of common men is to select the best among themselves to be leaders. Only James Madison seems to have grasped that ideal government might tend more toward a republic for purposes of the enumerated federal powers plus enumerated powers specifically denied to the states. For lesser issues, perhaps a purer democracy would be just as workable. However, in operation, it took scarcely a year to discover that the common man would not automatically select the best man he knew to be his representative. In fact, there exists a considerable populist sentiment, that wealth and success outside government are actually disqualifications for office. To some extent, this reverse social Darwinism is grounded in an unwillingness of the upper class to serve in government, perhaps because service to the country interferes with the lifestyle of unrestrained power and wealth which other occupations allow, but is forbidden to public servants. In any event, we persist in the fruitless argument whether America is a democracy or a republic; it was designed to be a mixture of both. Within the time of the first presidency, the unattractive realities of mixing human nature with elective politics transformed the meanings of the Constitutional document to something that was never written there, and other nations have largely failed to grasp. It apparently also worked a major transformation in its main author. James Madison first quarreled with his ally, Alexander Hamilton, and joined forces with the Constitution-doubter Thomas Jefferson. His mentor and idol, George Washington, essentially never spoke to him again.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

States rights no longer confronts America directly, because the Founding Fathers managed to get around it until the Civil War, and then the Fourteenth Amendment enabled the federal judiciary to attenuate state sovereignty somewhat further without eliminating the architecture of a federation of states. In other words, in two main steps we deprived the states of some sovereignty, but no more than absolutely necessary, and we took more than a century to do it. The European Union currently faces the same obstacle; this is how we solved it. If they can get the same result in some other peaceful way, good luck to them. Our framers used the language "Congress may...or Congress may not..." They only dared to strip state legislature of a few powers because they needed the legislatures to ratify the Constitution, a gun you can only fire once. Thus, they forbade states the right to issue paper money, the power to interfere in private contracts, and such, as enumerated in Article I, Section X, where the operative phrase is "The states are forbidden to..". The framers were willing to strip the unformed Congress of many more specific powers than the all-too-existing states; the Constitution can be read as a proclamation of the powers which any central government simply must possess. There might be other desirable powers, but here is the minimum. After eighty years, individual Southern states asserted their unlimited powers extended to nullification and secession, and because of a perceived need to preserve slavery would not back down. The Constitutional consequence of this national tragedy was the Due Process section of the Fourteenth Amendment, which has since been purported by the Supreme Court to mean that whatever the federal government may not do, the states may not do, either. However, Due Process traces back to the Magna Carta and has been so tormented by an interpretation that for the purpose stated, it is growing somewhat too elusive to remain useful. For historical reasons, we never gave a fair trial to the original proposal to address the federal/state dilemma. The Constitutional Convention was held in confidence, many delegates changed their minds along the way, and many ideas were more perceived than enunciated. It is plausible that the original strategy originated with Madison's teachers and emerged from many discussions, but there were several delegates in attendance with the sophistication to originate it. In a convention of egotists, there were even a few who would put their ideas in someone else's mouth.

The concept of how to curtail power in a non-violent way, can be called Regulatory Competition. Mitt Romney seemingly plans to promote the idea as a central feature of his political run for President of the United States, using a variant he has developed with Glenn Hubbard, the Dean of the Columbia University School of Business. The idea does still work reasonably well with state taxes and corporate regulation. If a state raises a tax, estate tax for example, in a burdensome way, people will flee to a state with more reasonable taxation. Corporations have learned how to shift legal headquarters to Delaware and other states which court them, and in really desperate cases will move factories or whole businesses. There is little doubt this discipline is effective, and little doubt that some cities and states have been punished severely for encouraging an anti-business environment. Whether the Fourteenth Amendment could be cleverly amended to expand this competitive effect without reintroducing segregation or the like, has not been seriously considered, but perhaps it should be. There are however not too many alternatives to consider.

As far as advising our European friends is concerned, it would be important to point out that the original version of Regulatory Competition completely depends for its effectiveness on the freedom to flee to some other state within the union. A common language is a big help to unity, but the ability to move residence is essential, so for practical purposes, both a common language and freedom of migration are required. Underlying such concessions is a sense of tolerance of cultural differences. That is unfortunately where most such proposed unions have either resorted to violence or failed to unite. And of course, the power which might otherwise be abused must then be shifted from the federal, back to a state level. What surfaces is a sort of one-way street? It remains far easier to devolve into little statelets than to unite for the benefits of scale. A working majority under the likes of Thomas Jefferson might have been assembled in the Nineteenth century but was held back by coping with the expanding frontier. During the Twentieth century, it would have been held back by the need to deal with world power. The Second Tea Party seems to have some inclination along these lines, but it remains to be seen whether some overwhelming need for world power will once more overcome the obvious national ambivalence about it.

The revised proposal for the regulatory competition takes the proposal to a different level, possibly a more workable one. Workers in the United States can freely move from one state to another but are restrained by national laws from equally free movement between nations. Removing that barrier makes the European Union attractive, although it inflames local nationalism. Since it seems more palatable to allow the currency to move, perhaps a little tinkering would be sufficient to permit uniform monetary rules to be the hammer which forces nations into permitting free trade on a global scale. The people themselves can remain at home in their national costumes, perhaps perfecting their religions in more churches and language skills in more schools. Meanwhile, the insight of Adam Smith would prevail for the long-term prosperity of everyone. Each party in a transaction feels enriched by it, the seller preferring to have the money, and the buyer preferring to own the goods. Multiplied a trillion-fold, these improvements in everyone's condition result in the steady enrichment of all.

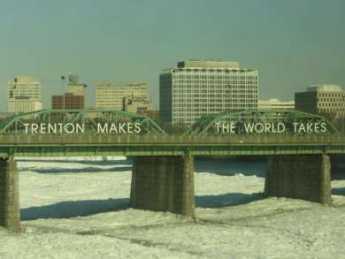

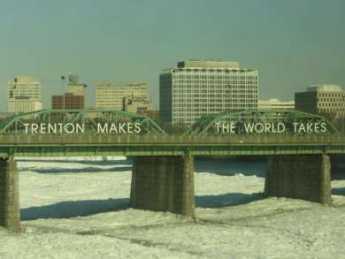

The Decision of Trenton (1782) Under the Articles of Confederation

|

| Trenton Makes the World Takes |

AS the American Revolution drew to an end, the time arrived to settle the inter-state grievance of Pennsylvania and Connecticut over King Charles II's ambiguity about who owned Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley, including the city of Wilkes-Barre. However, if they were all going to be United States citizens, it didn't matter much whether the residents of Wilkes-Barre (as it was now known) were governed by the laws of Connecticut or Pennsylvania. But bloody grievances die hard, and slowly. The genteel debates envisioned by the Articles of Confederation were not equal to settling blood feuds, but they tried. The two states selected judges to represent them, in a negotiated settlement which took place on neutral ground, Trenton, New Jersey. After protracted testimony and prolonged secret deliberation, the judges emerged with a very brief and unexplained decision: The Wyoming Valley belongs to Pennsylvania. Period.

Almost every scholar of this subject is convinced that the unwritten decision contained two other provisions. Connecticut was given a piece of Ohio, Western Reserve. And the Pennsylvania representatives privately assured the group that the Pennsylvania Legislature would in time recognize the land titles of the Connecticut settlers who were actually resident on Pennsylvania land. Unfortunately, it is hard if not impossible to enforce an agreement that is secret, and the Connecticut claim to Ohio was eventually eliminated, while the Pennsylvania promise to recognize the land titles of people whose ancestors killed our ancestors, was much delayed, watered down, and resented.

Caesar Rodney Rides Through the Rain

|

| Caesar Rodney |

If you have a quarter minted in 1999, you can see a depiction of Caesar Rodney riding through the rain, mud and heat, all night, to cast his July 2 vote for independence at the 1776 Continental Congress. There are no known painted portraits of Rodney, probably because his face was badly mutilated by cancer which ultimately killed him.

On July 1, Thomas McKean and George Read had split Delaware's votes in a tie, and McKean had urgently sent word to Rodney, the absent third vote, that he must come to Philadelphia quickly. Rodney was suffering from cancer. It may thus have been Thomas McKean's idea to invoke the concepts of the Treaty of Westphalia to escape hanging for armed rebellion, but Ben Franklin seems more likely. Once an idea like that gets started in a gathering, it quickly becomes everyone's idea. But Franklin was the only one to stampede a group and take no credit for doing so.

|

| Rodney |

Schoolchildren in Delaware can be forgiven for asking why Rodney wasn't in Philadelphia for the vote without being sent for. And we don't really know. Rodney certainly had plenty of other things competing for his attention, like being a Supreme Court Justice, the Speaker of the Delaware Assembly and the de facto Governor of the State, as well as being a Brigadier General in the Militia (he later was made Major General in charge of the garrison at Trenton). One has to suspect, however, that he had not expected George Read to vote against independence. Read, after all, had married the widowed sister of George Ross, who did sign the Declaration.

Asthma, a notoriously intermittent condition, may have been a worse impediment to Caesar Rodney's ride than his cancer. Although he was badly disfigured, cancer did not kill him until 1784. The prospect of riding eighty miles in the rain with asthma may well have been the reason Rodney held off until he was absolutely certain his vote was needed. The esteem and affection that Delaware holds for this farmer from Dover can be gauged by the fact that he remained the elected speaker until the day he died, and during his last three months, the legislature held its meetings in his house so he could be present.

3 Blogs

Articles of Confederation: Flaws

Some subtle features make the Constitution a vast improvement over the Articles of Confederation.

Some subtle features make the Constitution a vast improvement over the Articles of Confederation.

The Decision of Trenton (1782) Under the Articles of Confederation

The 1782 Decision of Trenton simply awarded the Wyoming Valley to Pennsylvania. Strong suspicions exist that other secret decisions were never made public. Like awarding the Western Reserve of Ohio, to Connecticut.

The 1782 Decision of Trenton simply awarded the Wyoming Valley to Pennsylvania. Strong suspicions exist that other secret decisions were never made public. Like awarding the Western Reserve of Ohio, to Connecticut.

Caesar Rodney Rides Through the Rain

When it looked as though Delaware was wavering on the Declaration of Independence, Caesar Rodney was summoned to ride through the rain to cast a deciding vote, in spite of advanced cancer of his jaw.

When it looked as though Delaware was wavering on the Declaration of Independence, Caesar Rodney was summoned to ride through the rain to cast a deciding vote, in spite of advanced cancer of his jaw.