0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Chapter Six: Constitutions: What's So Good About Ours; Why Does Europe's Fail Them?1793-70

The King's Last and Final Word

|

| King Charles II |

In 1662, King Charles II of England signed a charter, giving a strip of land in America to the inhabitants of Connecticut, and that land to stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. And then, eighteen years later, the same king signed a second charter, giving much the same land to William Penn. As lawyers say, these are the facts. In the many lawsuits, arguments, and wars which followed, no one ever seriously raised the point that King Charles was unaware that he was giving the same land twice, so it must be assumed he knew exactly what he was doing, and did it on purpose. In fact, he did this sort of thing many times, in other cases. The legal disputes which this double-dealing inspired, are therefore entirely concerned with whether the King had a right to do it, and if so, whether that right would normally be recognized (i.e. durable) when we threw off the King and became a republic. The matter was considered by many courts many times, and in every single case, the judgment was in favor of Pennsylvania.

|

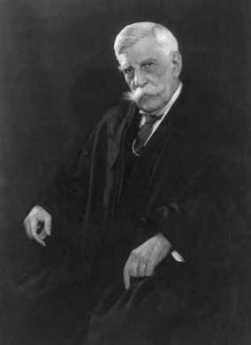

| Oliver Wendel Holmes Jr. |

Consider Connecticut's probable attitude toward all this. The colony was settled by Calvinist dissenters, so-called Roundheads for their surprisingly contemporary haircuts, adherents of General Cromwell, executioners of King Charles I during English Civil War. They gave Old Testament first names to their own children, and had always known they couldn't trust that licentious King. Giving their land away after he had promised it to them was just about what they always expected. When, after seventy years of growing families of fifteen to seventeen children, they discovered that Connecticut soil was merely a pile of pebbles left by the glaciers and covered with a thin layer of topsoil, they became even more convinced they had been cheated in the first place, and the bargain was no bargain. The reverse side of this enduring religious hatred will reappear in a few paragraphs.

The Proprietors of Pennsylvania, by this time no longer pacifist Quakers, but while descendants of William Penn, converted Anglicans and great friends with the King, took the matter calmly. The Connecticut lawyers were saying that if you sell or give away some land, it is no longer yours, so you can't give or sell it a second time. That is the modern view perhaps, but the English-speaking world was changing from a feudal, semi-nomadic, culture into a settled agricultural country where fixed boundaries were only starting to be important. That's where the world was going, but at the time King Charles gave away the land, it was far more important for the King to be able to reward successful underlings, and punish rebellious tribes, as the situation warranted. Ownership of land then seemed a nebulous thing at best, and the King was the best judge of how things should be divvied up.

Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced his book on The Common Law, by warning "The life of the law has not been logic, it has been experience." For life to go on and prosperity to endure, some decision must be made and held to, right or wrong. Stare decisis. That's of course fine for judges to say, but it must be observed that when people divide up on this question, where they stand depends heavily on where their ancestors stood on the English Civil War, and where their ancestors happened to be living during the so-called Pennamite Wars. As matters turned out, courts kept deciding in favor of Pennsylvania, and Connecticut kept bringing it up, again.

The Association (5)

|

| American Medical Association |

The American Medical Association has several hundred thousand physician members, all of whom consider themselves important members of their communities, hence important members of the AMA. "The Association" maintains a large, experienced, and frequently successful lobbying staff in Washington. It would be wildly impractical to permit every individual member of the Association to walk into the Washington office and give orders to the staff. Even when individual doctors have a very good idea, and the staff members thoroughly agree with it, it's never safe to assume the professional as a whole agrees. And in fact, it is always possible to find some doctor who violently disagrees, no matter what the topic.

So, a couple of centuries of experience led to a system of funneling physician opinion up to the line to the House of Delegates, and passing it through that narrow neck of the funnel before it is released to the Washington office as "policy". Sure, a couple of knuckle-heads can sometimes block a good idea at the narrow neck of the funnel, just as an occasional Leonidas can save civilization at this Thermopylae, against a bad idea. Sometimes an idea slides all the way through on the first try, and sometimes it is necessary to build up a head of pressure behind it. The fundamental question before the House of Delegates is not entirely whether a proposition is a good idea or a bad one; an equally important question is whether it likely reflects the prevailing viewpoint of the profession.

My first salvo in the campaign to win AMA approval for Medical Savings Accounts was a letter to Jim Sammons, the Executive Vice President. He wrote back promptly that he had read the Medical Savings Account proposal three times, and still didn't understand it. Although my opinion of him was never quite the same, he did me the favor of demanding simplicity, to be more quotable. An IRA for Health. An IRA plus a catastrophic policy. What's good about that? Cheaper. What makes it cheaper? Compound interest. How does it help poor people? More people can afford to buy something that's cheaper. Sammons said, ok, I can live with that.

The letter to the EVP turned out to be a good idea because it established my claim to ownership. A few months later I arrived in Chicago with a crisp, brief zinger of an MSA proposal, only to find that somebody from Louisiana was attending the same meeting with an almost identical proposal, called CHIP. Mike Smith was president of the Louisiana Medical Society, and not only had the same idea but personally had a lot of Louisiana oil money which he freely spent on professional packaging of his presentation. Mike and I suspiciously circled each other like two wildcats for a few hours, but we had so much in common that very shortly we were the best of friends, remaining so for years until his unfortunate death. He introduced me to his Southern friends, I introduced him to my Northern ones, and the idea itself picked up some allies on its own merits. It had a fairly easy time of it in the House of Delegates. However, it was referred to a committee for polishing and deeper consideration. Six months later it had disappointingly picked up quite a lot of unforeseen opposition, probably after the hospital and insurance executives heard about it. It took another six months to fight through a wall of specious argument, but an endorsement of the Medical Savings Account did become a policy of the AMA and the eager Washington staff was thus free to run with it.

It has remained AMA policy ever since, and the main technical problem for its main sponsors became one of keeping the idea alive in a House of Delegates with constantly shifting turnover. The AMA is like the court system; it doesn't like to keep revisiting an issue that is settled policy. Too many other members have proposals requesting attention, so why should we go on reaffirming old matters? However, the proposal was stalled in Congress, and for the momentum, we needed to keep beating the drum with variations which somewhat stretched the patience of the more senior members of the House of Delegates. To them, I apologize, with gratitude for their tolerance.

But what was the matter with Congress? What was the matter with the editorial page of the New York Times? I was always uneasy about a protracted debate because reducing the cost of medical care (from the patient's point of view) was apt to translate into reduced income for doctors. I was leading a procession of self-employed entrepreneurs into a proposal to cut their own income for the benefit of the public; how long could physician enthusiasm be maintained for that? I'm proud to say the answer is at least twenty-five years.

Even in retrospect, I am a little surprised that even such sophisticated students of medical economics could remain focused for so long. They might have come to regard the sponsors of MSA as being on an ego trip, or else nutty fanatics obsessed with a lost cause. Or they might have joined the young newcomers in fearing that such determined opposition at a national level might signify the opponents were somehow right to oppose it. The arguments advanced by the opponents really seemed to have very little merit, but perhaps in private, it might be possible to sympathize with some embarrassing circumstances that explained the vigor of the resistance without crediting its excuses. Political debate after all, even in scientific organizations, quite characteristically wraps venal motives in a cloak of logic and altruism. I remained fearful for years that the House of Delegates would shrug its shoulders and let the opponents have their way. That they never, ever, did so was probably related to medical care being physician home turf; where you get used to hearing a lot of dumb arguments, but you don't have to credit them with any merit until merit is displayed. You can tell doctors a lot of fairy tales about architecture or investment banking perhaps, but if you talk medicine with them, you better have your facts.

Whenever my colleagues would privately draw me aside and ask why in the world a lot of people were so resistant to the MSA, I had to tell them I was not entirely certain. However, it was notable that three groups had important things to lose, and would probably fight to preserve them. The Medical Savings Account threatened the eighty-year-old pricing preferences between hospitals and insurance companies. Secondly, it threatened the sixty-year-old preferential healthcare pricing for members of organized labor. And finally, the politicians who were so anguished about the uninsured population might possibly be more interested in preserving the grievance than achieving its solution.

I can never remember a private conversation of this sort that didn't satisfy the doctor who asked the question. And I also never met a representative of health insurance, hospital administration or organized labor who would admit any truth to it.

Germantown After 1730

|

| German Quaker Home |

The early settlers of Germantown were Dutch or German-speaking Quakers. They were proud of the craftsman class but, unfortunately, that made them rather poor subsistence farmers. With a whole continent stretching beyond them, professional farmers would not likely choose to settle on a stony hilltop, two hours away from Philadelphia. Germantown's future lay in religious congregation, in papermaking, textile manufacture, publishing, printing and newspapers. Plenty of stones were lying around, so stone houses soon replaced the early wooden ones. Since Philadelphia in 1776 had only twenty or so thousand inhabitants, and only thirty wheeled vehicles other than wagons, it was not too difficult for Germantown to imagine it might eventually eclipse that nearby seaport full of Englishmen. Two wars and two epidemics brought those Germantown dreams to an end, but in a sense, those calamities were stimulants to the town, as well.

In 1730 real German peasants began to arrive in large numbers from the Palatinate section of the Rhine Valley. They arrived as survivors of a horrendous ocean sailing experience, packed in such density that it was not unusual to find dead bodies in the hold, of passengers that had only been supposed to have wandered into a different part of the ship. Quite often, they paid for their passage by selling themselves into what amounted to limited-time slavery, and a customary pattern was for parents to sell an adolescent child into slavery for eight or ten years in order to pay for the voyage of the family. They were uneducated, even ignorant, and often were proponents of small new religious sects. All of that made them seem to be a primitive tribe in the eyes of the earlier settlers. But they were professional farmers, and good at it. They knew, and a quick tour of Lancaster County today confirms their belief, that if you had a reasonable amount of very good land, you could live a life that approached that of the craftsmen in comfort, and usually far exceeded them in personal assets. They have therefore taken a long time to rise from farm to sophistication, while the already sophisticated craftsmen in Germantown wasted no time in abandoning farming. The peasant newcomers arrived in Philadelphia, made their way to nearby Germantown, learned a little about the new country and the refinements of their Protestant culture -- and then pressed on to the great fertile valley to the West, where the way had been paved by those twenty-five German families who had landed on the Hudson River several decades earlier and come down the Susquehanna via Cooperstown. Only a minority of the after-1730 Germans stayed on permanently in that steadily growing little German metropolis on a hill, and none of the very earliest German pioneers further west had even landed in Philadelphia.

During this period, this Athens of German America also invented the Suburb. The pioneer of this concept was Benjamin Chew, the Chief Justice, who built a magnificent stone mansion on Germantown Avenue, which was to become the main fortress of the Battle of Germantown in the Revolutionary War. Present-day visitors are still impressed with the immensity and sturdy mass of this home. Grumblethorpe, Stenton and a score of other country homes were placed there. Germantown in 1750 still wasn't a very big town, but it was plenty comfortable, quiet, safe, intellectual and affluent. Its first disruption came from the French and Indian War.

Lewis Harlow van Dusen, Jr. (1910-2004)

|

| Croix de Guerre |

Lew van Dusen was one of the great story-tellers of a story-telling city. In one continuous lunch conversation he could string together personal anecdotes about Lloyd George, Lawrence of Arabia, William Bingham, the making of the hydrogen bomb, the Croix de Guerre (which he had been awarded), Nicholas Murray Butler, several Supreme Court Justices, Harvard Law School (where he led the class), and on and on until the waitress would just go ahead and clear the table. He even told of his own great suffering as a boy sitting at proper Philadelphia dinners, where it was a firm rule that acceptable topics of conversation were limited to the Wimbledon lawn tennis matches and the sinking of the Titanic.

When the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case of State Oil v. Kahn came up for arguments, he and I rode together on the Metroliner down to Washington, stayed at a club there, and after the hearing took the train back to Philadelphia. During the entire time, Lew never stopped talking, and his voice was very loud. There was the time in Macao when a retired British diplomat came up to him and said he knew the history of every gravestone in the cemetery for foreigners, except five, and two of those names were on the letterhead of Lew's firm (Drinker, Biddle and Reath). Drinker, it turns out, was American consul and discovered that all of his guests were poisoned by the cook. He traveled all night, getting stomachs pumped out, but not his own, and died the next morning from the poison. Biddle, on the other hand, was also a physician interested in Yellow Fever and died of it when he contracted the disease from one of the subjects.

There was the time when he was the young guest of Nicholas Murray Butler at a luncheon with British Prime Minister Lloyd George. "Tell Mr. Roosevelt," said George, "That Social Security is nothing but a dole."

And the time when King George gave everybody the day off on his 25th Anniversary as King, so they played cricket. His teammate was Lawrence of Arabia, and after the game, Lawrence hopped on his motorcycle and rode off down the road to be killed. Lew was the last person to see Lawrence alive.

Well, when you get to the Supreme Court, the public stands in line on the steps, out in the rain. But the lawyers go around to the back door, where there are a lounge and a lunchroom. Inside two minutes, Lew was surrounded by lawyers as he told more stories. One of them tugged my sleeve and asked, "Is that who I think it is?" I said I supposed so, although who he had in mind is still a mystery to me.

State Oil turns out to have been as important to antitrust law as we supposed it would be; the fine points of vertical integration were afterward explained to me. And finally, I was told how, when he was chairman of the Ethics committee of the American Bar Association, Lew's committee caused the ABA to reverse its long-standing opposition to cameras and audio equipment in courtrooms. The effect of this has been slow, but gradually courts are permitting the televising of trials, and eventually they probably all will permit it. But not yet the U.S. Supreme Court. Non-lawyers still stand in the rain outside, and if there are no seats left inside, too bad.

Highway Beautification

|

| Prince Grigory Potemkin |

Someone who has traveled in modern China -- and is at all observant -- knows that the extensive slums and trashy wastelands of the Inner Kingdom are systematically hidden from tourist's eyes by fences and plantings of tall trees. In a few years, the trees will grow a few feet taller and fully conceal what is behind them, but today modern tourist buses are high enough so you can see over the treetops if you look. When American tourists notice this, they are very smug.

The term Potemkin Village is a somewhat exaggerated term for the process Grigory Potemkin used to clean up the villages that his girlfriend Catherine the Great passed through on her visit to southern Russia and Crimea. He apparently did not construct whole fake villages as enemies claimed, but he was unnecessarily forceful,

|

| West Philadelphia, at one time. |

let us say, in his efforts to smarten things up. After taking a few rides on Philadelphia's suburban commuter trains, or a boat ride up to its rivers, the idea does cross most minds that we could use a Potemkin in charge of our Streets Department, or maybe a Communist Chinese on loan. We have miles, maybe even hundreds of miles, of overgrown weeds along our embankments, spiced with the discarded trash of historic duration. Since nobody wanted to live next to coal-burning locomotives, and most people even dislike the noisy though cleaner replacements, the houses along the railroad clearly deserve to be hidden. That's true in almost every town in the world (not Japan, not Switzerland) and it's deplorably true in our Philadelphia. Seaports and riverbanks are a mess everywhere, too, and we are certainly in style in that department as well. Why can't the Schuylkill look like the Seine, next to the cathedral of Notre Dame?

So the Chinese have combined the concept of cleaning up their public spaces, which we applaud, with the concept of hiding the economic truth, which we sneer at. Maybe we should give some thought to a spin campaign, the essence of which is a metropolitan crusade to pick up the trash, build some strategic fences, and plant a whole lot of tall evergreens along with the public ways. We've made a good start with Boathouse Row; why not extend it to Gray's Ferry, or even to Norristown? The idea is not a new one; Lady Bird Johnson made it her main goal in public life.

In 1965, Lyndon Johnson used his famous powers of legislative persuasion to give his wife what she wanted. The Highway Beautification Law of 1965 was passed by Congress on Lady Bird's birthday, with everyone in the gallery dressed in evening clothes. With the vote counted and enormous standing applause registered for fifteen minutes, the whole group traveled over to the White House for a signing of the law with nineteen pens. There followed the birthday party at the White House, to end all birthday parties. Highway billboards were a thing of the past.

That was forty or so years ago, and unfortunately, the billboard companies didn't like it at all. Through administrations both Democrat and Republican, the Department of Transportation has never issued regulations, so Highway Beautification was never implemented. It represents just one more unwritten aspect of the Constitution that James Madison and his friends didn't fully anticipate.

5 Blogs

The King's Last and Final Word

King Charles II did give Wilkes-Barre to Connecticut first, and the same king did later give the same land to William Penn. Unfortunately for Connecticut, at that time the last word was all that mattered.

King Charles II did give Wilkes-Barre to Connecticut first, and the same king did later give the same land to William Penn. Unfortunately for Connecticut, at that time the last word was all that mattered.

The Association (5)

The American Medical Association claims to represent the collective views of the medical profession, and sometimes its detractors scoff at that idea. AMA really has an elegant system for hearing the voice of a single physician, and if it likes what it hears, is really good at magnifying that voice.

The American Medical Association claims to represent the collective views of the medical profession, and sometimes its detractors scoff at that idea. AMA really has an elegant system for hearing the voice of a single physician, and if it likes what it hears, is really good at magnifying that voice.

Germantown After 1730

Germantown became the spiritual and intellectual capital of German America as immigrant farmers passed through on the way to better farmland. When Benjamin Chew built his mansion there, it became an affluent suburb as well.

Germantown became the spiritual and intellectual capital of German America as immigrant farmers passed through on the way to better farmland. When Benjamin Chew built his mansion there, it became an affluent suburb as well.

Lewis Harlow van Dusen, Jr. (1910-2004)

rode together on the Metroliner down to Washington, stayed at a club there, and after the hearing took the train back to Philadelphia.

rode together on the Metroliner down to Washington, stayed at a club there, and after the hearing took the train back to Philadelphia.

Highway Beautification

When American tourists notice this, they are very smug.