0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Chapter Thirty Curtis-Those Delivery Trucks

Curtis: Those 1905 Delivery Trucks

|

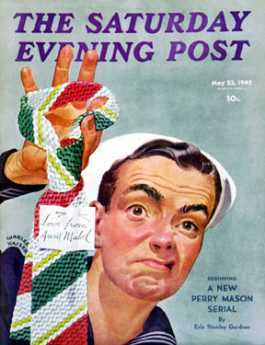

| The Saturday Evening Post |

The Curtis Publishing Company was symbolic of Philadelphia in a lot of ways, like the silhouette of Ben Franklin on its masthead, the deliberately old-fashioned type font of the Post's title above the Norman Rockwell paintings on the cover. Since Curtis stopped publishing magazines, the sturdy old buildings have been converted to modern office space. If you stroll around today, you get a completely misleading impression of the headquarters. To some extent, the present lavish interiors are a response to the Tax Act of 1975, which specifies that the cost of a rehabilitation project must exceed the previous value of the building. And to some extent, the present luxury reflects the deluded ideas of architects and dreamers about the proper lifestyle for captains of industry. To view this rehab, you might suppose:

|

| Louis Comfort Tiffany |

If you came to visit Curtis in Philadelphia, you would be invited to have lunch in the Down Town Club, and then enter the office complex proper through ornate bronze doors, going down spectacular gleaming interiors past a splendid indoor fountain at the foot of a magnificent huge marble staircase leading who knows where. There would be opulence on all sides, punctuated by an enormous glass mosaic constructed by Louis Comfort Tiffany on a design by Maxfield Parrish. Curtis must have had a wow first floor, designed to impress visitors, and every bit as successfully impressive as anything in New York or Washington DC. In case you didn't get the point, this looming structure did its looming right across the street from Independence Hall. That's the impression you would get today, without a uniformed guide to explain things to you. But as a matter of fact, those high, high ceilings were meant to enclose printing presses, which are notoriously noisy, smelly, and greasy. This was a place of business, a manufacturing plant, not a tourist attraction.

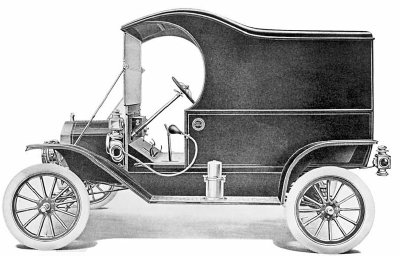

The real symbolism of no-nonsense Philadelphia manufacturing could be seen, every day on the streets. It was those funny old delivery trucks. Everyone in Philadelphia in the morning was familiar with these relics, great lumbering elephants traveling at about five miles an hour or less making grinding noises, slowing up traffic, looking terribly old fashioned. As a matter of fact, they were built in 1905 and were powered by electric batteries. Indestructible, requiring neither maintenance nor fuel except for recharging the batteries overnight. They did their job of transporting paper and magazine product back and forth from Washington Square to the printing plant at Sharon Hill, and there was absolutely no economic justification for replacing them with something more expensive. Their cast iron construction was such that there would probably never be an economic reason to replace them; funny looking, maybe, but they were money in the bank. Philadelphia loved them like a dotty old maiden aunt.

|

| Liberty Bell |

But just imagine the impression they gave the two-martini crowd when they came down from New York for a job interview or for business negotiations. The trucks symbolized the fuddy-duddy city with its fuddy-duddy magazine. Imagine working for a place that would tolerate those things, and what's even more unimaginable, the local yokels actually defended them. The word "cool" was invented to represent everything that these old trucks were not; didn't want to be. Just seeing one of them was enough to make you take your hard-leather heels back to Madison, and Lex, and The Village. Even after first impressions faded, the true symbolism of those trucks was troublesome to glitterati. The impression the trucks gave to visiting readers of the Post was quite in keeping with the magazine's decades-long message of hard work, frugality, and no-nonsense pruning of expenses. A chance visitor to Independence Hall could plink the Liberty Bell and then wander over to that Taj Mahal on the West side of Sixth Street, quite likely thunderstruck by the interior. Out of town readers would, of course, have been even more dumbstruck to see the mansion that the Curtis family lived in on Rittenhouse Square and elsewhere, but all that was at a discreet distance. And then, one of those nice old trucks would come lumbering along. Now that's the spirit. That's the message of crafty old Ben Franklin. Who cares what people think about the outward show, especially those, ugh, people from New York.

Working Girls Get the Faints

|

| Curtis Building |

Curtis Publishing Company once covered a full city block of Philadelphia, from Sixth to Seventh Streets, Walnut to Chestnut. The northern half of this complex was the Public Ledger Building, once housing a failed diversification move into newspaper publishing and later rented out as commercial office space after the newspaper died. On the top floor of the Ledger Building was the Down Town Club, quite a palatial meeting place for the whole publishing industry which stretched for blocks around. Both Curtis-owned buildings have the same architectural design and together make a massive looming presence next to Independence Hall on one street and Washington Square on the other. To build from Walnut to Chestnut means shutting off Sansom Street in the middle, and that permits the jewelry trade to nestle in a cul de sac on the West side of the publishing complex.

So Curtis was once a little city within a city, and most of the rest of the town only saw its facade and the crowds of people coming and going through the entrances. To a neighborhood doctor on an emergency call, however, it was almost exclusively inhabited by young women. Kitty Foyles, you might say. I certainly formed that impression after having a medical office two blocks away, getting occasional calls.

|

| Christopher Morely |

So far as I can remember, Curtis had only one medical problem, repeated over and over. An anguished call would come that someone at Curtis was unconscious, come immediately, take the elevator to the third or fourth or fifth floor. At the elevator, the doctor would be met by a somewhat older woman, obviously the den mother of the working girls. Into the ladies room, we would go, where a young woman was usually sitting on a couch looking sheepish, although occasionally she was still passed out. The key finding was a very slow pulse. She had fainted, she was better, and now what. It was Curtis policy to send the fainters home after the faint, and I never could see any particular objection to that.

For me, there were never any men to be seen, at Curtis. Surely there must have been dozens of writers and editors and advertising people, but somehow they would vanish when one of these fainting things happened. Curtis was nothing but women when I was there, mostly watching me like a beach full of seagulls, watching a fisherman.

Cecilia Beaux, Portraitist of the Grand Manner

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) was certainly the most famous woman portraitist of her time. She had the misfortune of being a contemporary of Mary Cassatt, who enjoyed the reputation of the finest woman Impressionist at a time when the Art world disdained traditional painting techniques in an Impressionist stampede. So, although these two temperamental artists might never have been chums, much of their famous rivalry was probably invented for them by art world politicians. In time, the assessment will emerge that these two well-born Philadelphia ladies were each the world's female leaders of two competing schools of art. Comparisons of the two will also have to be filtered through the fact that Cassatt was a rebel who spent most of her life in Paris, while Beaux was a prominent faculty member of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for twenty years. Strikingly beautiful herself, she was gifted, elegant and fiercely ambitious. Meow.

Once Beaux had established a reputation as a portrait painter, she shrewdly began to select her subjects. She wanted famous men (Henry James, for example) and beautiful women subjects. She made the mistake of turning down her niece, Catherine Drinker Bowen, because she didn't have the right kind of cheekbones. She learned, of course, that it's unwise to tell a famous author she is ugly.

Cecilia Beaux's main competitor in the portrait game was John Singer Sargent, who was if anything a better painter but a stammering social dud. Sargent remained a life long bachelor, Beaux a spinster. Her mother had died in childbirth, and it seems likely that terror of pregnancy was an important part of her personality, during the pre-antibiotic era when such fear was fairly justified. As a young woman, she turned down proposals by the dozen, and in maturity, she had a succession of apparently platonic but intense relationships with handsome men twenty years her junior. During the late Victorian era, this sort of thing was not rare, although medical advances have apparently largely eliminated it. To return to her competition with Sargent, the personality differences probably account for his haunting portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, while Beaux is notable for arresting portraits of rich, famous and beautiful women, and an equal number of well-dressed, handsome men.

3 Blogs

Curtis: Those 1905 Delivery Trucks

Working Girls Get the Faints

Cecilia Beaux, Portraitist of the Grand Manner

|

The streets around the Curtis Building were populated with huge solid-tire, battery-driven delivery trucks. They were built in 1905, cost almost nothing to run, and crept along at 5 miles an hour. It was impossible not to notice them, and that was the main idea.

The streets around the Curtis Building were populated with huge solid-tire, battery-driven delivery trucks. They were built in 1905, cost almost nothing to run, and crept along at 5 miles an hour. It was impossible not to notice them, and that was the main idea.