1 Volumes

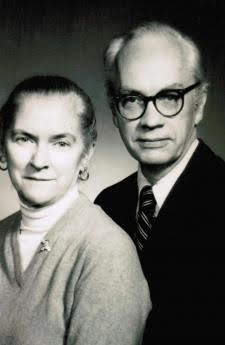

Mary Stuart Blakely Fisher, 1922-2006 MD Photos

It's hard to speak of her in anything but superlatives.

Mary Stuart Blakely Fisher, MD

Working as a woman doctor in the days when women were limited to 10% of the admissions to many colleges, and often excluded entirely, Mary Blakely graduated first in her co-ed class at Binghamton (NY) High School, followed by first in her class at Bryn Mawr College, and the first in her class at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. In fact, she had the highest grades in five years at Bryn Mawr and was selected as a medical intern at the Massachusetts General Hospital, going on to the nation's most prestigious radiology residency under Ross Golden at Presbyterian Hospital in New York, and subsequently with Aubry Hampton. During much of that time, she lived in Philadelphia and commuted on the train to New York. She had married me a year earlier, and the train conductor grew visibly more anxious as she became increasingly pregnant during the several-month commute from Philadelphia's Broad Street Station to Penn Station in New York. Both railroad stations have since been torn down, and the baby she was carrying has been retired for ten years after being Managing Director at Morgan Stanley.

The State of Pennsylvania required a rotating internship, and while I still believe that is the best sort of internship, it was particularly galling to have the reason given that her internship was the reason for refusing to grant her a Pennsylvania license. So she got a job at the Philadelphia Veteran's Hospital, and later at Philadelphia General Hospital, the City's charity hospital of three thousand beds. Well, she never mentioned this Philadelphia affront to a premier academic Boston institution, but I didn't. Perhaps church politics are more vicious still, but this little episode illustrates how very nasty medical politics can get. Perhaps it is a feature of the human personality everywhere, but some situations freely tolerate it, while a few others just don't.

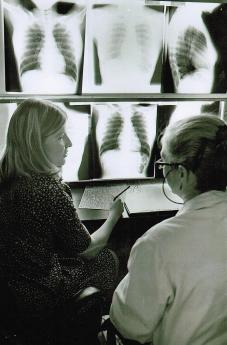

Well, in time she was offered the chairmanship of just about every Radiology department in Philadelphia, and turned them down, saying she didn't want to be chairman of any department. Perhaps she meant any department in Pennsylvania, but she never did make her feelings known. Eventually, she did become Professor of Radiology at Temple University, where she happily taught the residents for many years, during the course of which she was given the Madam Curie Award, the Lindback Award, and various other honors. She had an amazing facility to start dictating reports on x-rays before they were completely out of the envelope and always won the interdepartmental contest for diagnosis of strange films, to the point where other, mostly male, radiologists were afraid to compete with her. She won the Lindback Award for Excellence in Teaching. I used to say I didn't know whether she was any good or not, but I never met a radiologist who wasn't thoroughly intimidated by her ability to make a strange diagnosis at a glance. All her life she got along with five hours of sleep, invariably getting to bed after me and getting up the next morning before I did. Essentially, there were twenty-eight hours in her day.

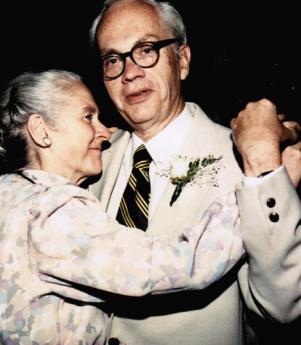

So it wasn't just radiology where she excelled. Her father once told me there was nothing she could turn her hand to, where she didn't excel. Especially female skills. She was past the point of competing with males and beating them, but female skills were something else. She was a master cook, a demon housekeeper, a champion seamstress, a masterful dinner partner. Athletics were never attempted because she knew very well that men hate to be beaten at golf or tennis. It was the era of Kathryn Hepburn and Grace Kelly, and with a minimum of makeup, she turned heads where ever she went with that Bryn Mawr look about her and her painfully simple clothes. Several of my classmates, usually from Princeton, was struck dumb by her looks. For example, my book editor from Macmillan had a classmate of mine for his doctor. That Park Avenue physician never married and confined to the editor that he had been carrying a torch for her, all his life. It brought to mind the boastful lines from Congreve, in The Way of the World:

"If there be a delight in love, 'Tis when I see, The heart that others bleed for -- bleed for me."

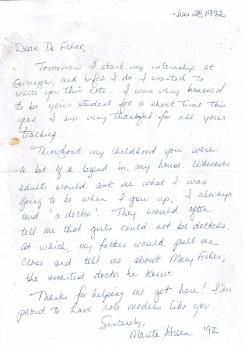

Teacher, Mentor receives Marie Curie Award Decenber 3, 1992

|

| Mary Stuart Fisher, MD and AAWR President Katherine A. Shaffer, MD. |

Mary Stuart Fisher, M.D described by her peers as a consummate radiologist and widely recognized teacher, received the Marie Curie Award from the American Association for Women Radiologists (AAWR) at the group’s luncheon on Tuesday. As chairman at Philadelphia General Hospital, and more recently, a professor in the Department of Diagnostic Imaging at Temple University Hospital, Dr. Fisher has taught legions of medical students radiology residents, and colleagues over the past 25 years.

Early in her career, Dr. Fisher was acknowledged as a clinical expert in GI radiology. At Temple, she created the radiology teaching program for medical students, now one of the most popular in the school, and she developed a specialty section in chest radiology. She directed the residency teaching program for several years as well.

Distinguished resident

The AAWR also presented the 1992 Distinguished Resident Award to Elizabeth L. Gerard, MD, a senior resident in diagnostic radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Gerard was a springboard and platform diver with the U.S. national team. She was a finalist in the 1984 Olympic trials while attending medical school at the University of California San Diego. She subsequently interned at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and has completed a clinical research fellowship in MR imaging. Currently, she is a GI interventional radiology fellow and continues her research in MR imaging with clinically applied work.

Radiology October 2006 In Memoriam

|

Dr. Mary Stuart Fisher, the mother figure of Philadelphia Radiology, died on April 24, 2006, at the age of 83 years.

Dr. Fisher was active in her faculty position at Temple University Medical School (Philadelphia, Pa) until the last three 3 years of her life. For more than 50 years, she taught hundreds of residents and thousands of medical students about radiology at the Philadelphia Veterans Administration Hospital, the Philadelphia General Hospital, and the Temple University Medical School. She was a role model for many of the women among them.

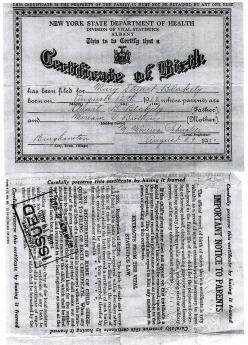

Dr. Fisher came into medicine at a time when women were accepted as students but not always as equals. She graduated first in her high school class in Binghamton, NY, first in her class at Bryn Mawr College, and first in her class at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (New York, NY) in 1948. She completed her internship at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and her radiology residency at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York City.

After a fellowship with Groover, Christie, and Merritt (Washington, DC), a private group that maintained its own training programs. Dr. Fisher accepted an offer at the Philadelphia Veterans Administration Hospital, as shared service for several medical schools. She taught students and residents from all five of them. After 8 years, she came to Philadelphia General Hospital, also a service shared by several medical schools. When the Philadelphia General Hospital closed in 1975, her former resident, Marc Lapayocher, head of diagnosis at Temple University, recruited her to the position where she spent the rest of her 50-year academic career.

Dr. Fisher was a member of the American Medical Association, the Philadelphia County Medical Society, and the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the Radiological Society of North America, and the American College of Radiology, the Association of University Radiology, and the American Association of Women in Radiology, the Society of Thoracic Radiology, and the Pennsylvania Radiological Society. She served as a consultant to the National Board of Medical Examiners.

Dr. Fisher’s bibliography contains some 50 papers and chapters. She received her most pleasing award for teaching from Temple University, including the Golden Apple award, which was selected by medical students in 1990. She received the Honored Radiologist award from Pennsylvania Radiological Society in 1985 and the Outstanding Educator award from the Philadelphia Roentgen Ray Society in 1992. The same year, the American Association for Women Radiologists gave her the Marie Curie Award, its highest recognition. The Philadelphia Roentgen Ray Society renamed its annual Outstanding Educator award for her in 2006.

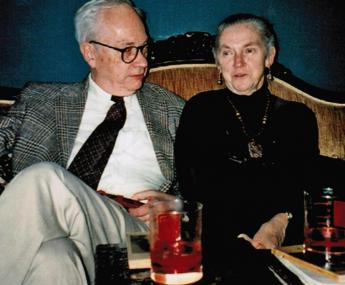

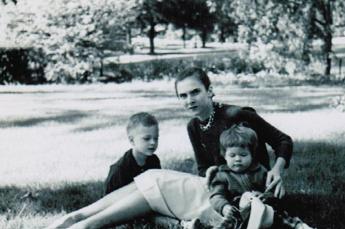

She is survived by her husband, George Ross Fisher III; daughters, Miriam and Margaret; and sons George and Stuart.

Otha W. Linton, MSJ

Michael S. Huckman, M.D.Letter

Rush-Presbyterian St. Luke’s Medical Center

1753 West Congress Parkway, Chicago, Illinois 60612

(312) 942-5781

Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine

Richard E. Buenger, M.D. Chairman

Ernest W. Fordham, M.D. Vice Chairman

Computed Tomography and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

John W. Clark, M.D. Director

Gastrointestinal Radiology

Richard Gardiner, M.D. Director

Claire S. Smith, M.D.

Alvin H. Felman, M.D., Director

Radiology Residency Program

University Hospital of Jacksonville

655 West Eighth Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32209

Dear Al,

Thanks for your letter of August 2, 1984. I do not participate in the decision-making involving the CT Ultrasound fellowship, but I’m sure Jerry will give the application every consideration. Congratulations on being asked to give the lecture in honor of Mary Fisher. It’s hard to speak about her except in superlatives. As you may know, she and her husband were known as the Duke of Harrisburg and Duchess of Altoona. She said that it had to do with the fact that both of their ancestors had received large grants of land from William Penn and from some English royalty.

I recall that Mary religiously attended the Thursday night conferences. She would hop in her 53 Chevy (or her Checker Limo) at about 4:00 p.m., drive home to Haddonfield, cook dinner and drive back to be on time for the conference. That was certainly the ultimate in dedication.

You might want to mention something about her little book which held the densities of various grades of glass and fish bones and a bunch of other facts that weren’t worth committing to memory but were certainly worth knowing. If I think of anything else I will let you know.

Warmest personal regards,

Michael S. Huckman, M.D.

MSH/vdb

Letter from Radiology Associates Albert Einstein Medical Center

Radiology Associates

Albert Einstein

Medical Center

York and Tabor Roads,

Philadelphia, Pa. 19141

Alvin H. Felman, M.D.

Department of Radiology

University Hospital

of Jacksonville

655 West Eighth Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32209

Dear Al,

I’m sure that by now you’ve decided that either the letter you sent me was lost or that the cold here in Pennsylvania has softened my brain so that I was unable to reply. While the later impression is probably correct, it did take me a little while to get together some of this material. Enclosed in this envelope you will find slides of Drs. Herman Ostrum, Russel Miller, and Bernie Widman. You will also find a group picture of many of the residents and staff from the time while we were residents. You’ll note that the picture does include Bill Serber, Mary Fisher and Herman Ostrum. Russ Miller and Myron Blumberg were evidently not around on that day, which is actually nothing different than Myron’s current status.

There is also a copy of a portion of the program from the first annual dinner of the Blockley Radiologic Society which may be of some interest.

I really don’t have any informative anecdotes about Mary. Although I believe then and still believe now that she is the finest all-around Diagnostic Radiologist in the Philadelphia area, her personality is such that it does not lend itself to humorous incidents. I still see her almost monthly at the Philadelphia Roentgen Ray Society Dinners and often sit with her. She is a marvelous raconteur and a dedicated physician and family member. She often speaks to me of her children and occasionally of her travels. When PGH closed she was instrumental in a massive effort to transfer most of the teaching file from the Radiology Department at PGH to the College of Physicians where it now resides.

I hope that some of this information is helpful to you. I look forward to your presentation honoring Mary and to seeing you at the Pennsylvania Radiologic Society in May.

Warmest regards,

Arthur D. Magilner, M.D.

Chairman, Dept. of Diagnostic Radiology

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University / New York, N.Y Letter

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University / New York, N.Y.

Department of Radiology

David H. Baker, M.D.

James Picker Professor and Chairman

622 West 168th Street

Telephone: (212) 694-6408

January 14, 1985

Alvin H. Felman, M.D.

University Hospital of

Jacksonville

655 West Eighth Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32209

Dear Al:

Dashiell Hammett, Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, and Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle collaborated and have finally found a picture of Dr. Fisher which I have had made into a slide and I am sending to you. We had no record of Dr. Fisher as a resident but we were able to find Mary Stuart Blakely as a medical student who graduated in 1948. She interned at the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1949 and started her radiology residency here on October 1, 1949. She was appointed by Dr. Ross Golden. She wrote to Dr. Golden on July 30th, 1949 from Venice where she was spending the summer with her parents. The letter on July 30th noted that her address in Paris to the middle of August would be American Express Company, in Edinburgh until the end of August and in London through the first week in September. Sounds like a nice summer. A letter from Dr. Loeb to Dr. Golden on September 7 states that Dr. Blakely was the number one student in her class and was offered an internship at the Presbyterian Hospital but preferred early acceptance at Massachusetts General where she went. While she was in medical school she won the Janeway Prize and was equally glowing. Her record then becomes a little bit sparse. The last two notes in her record are one from Ross Golden to Dean Rappleye suggesting that Mary Blakely Fisher, so she has obviously married in the interim, had resigned her assistant Residency as of May 1 to have a baby and to follow her husband to Bethesda. On the last notation, there is a letter to Dr. Christie from Dr. Golden suggesting that Mary Blakely Fisher was moving to Washington with her husband George Fisher. He also suggested that she was an outstanding student and an excellent resident and he recommended that she was an outstanding student and an excellent resident and he recommended that she contact Dr. Christie to be able to finish her training in the Washington area and that is the last we know of her.

I hope this has been helpful. It took a lot of doing. You owe me one.

Sincerely,

David H. Baker, M.D.

DHB/mja

MVP of the Medical School

Temple University Letter: Christian R. and Mary F. Lindback Foundation award

Temple University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122

April 17, 1985

Dr. Mary S. Fisher

203 Chews Landing Road

Haddonfield, NJ 08033

Dear Dr. Fisher,

I am pleased to inform you that you have been selected as one of the six members of the faculty to receive the Christian R. and Mary F. Lindback Foundation award for distinguished teaching. The official presentation will be made at the luncheon which will be held at the Hilton Hotel in the Ballroom/Assembly Salon A and B immediately following the Commencement exercises on Thursday, May 23. You are, of course, invited to bring a guest.

Historically, Temple University has been an institution in which the importance of excellence in teaching is paramount. Accordingly, we are most grateful to the Lindback Foundation for making possible the opportunity to honor those of you who have been chosen for special recognition.

This is confidential information until the University releases it.

I congratulate you and look forward to the opportunity of honoring you publicly at the Commencement luncheon.

Sincerely,

Peter J. Liacouras

PJL: dd

University Hospital of Jacksonville Letter

University Hospital of Jacksonville

655 West Eighth Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32209

Telephone 904-350-6899

Gene Mc Leod

President

May 22, 1985

Michael B. Dooley, M.D.

Department of Radiology

Phoenixville Hospital

140 Nutt Road

Phoenixville, PA 19460

Dear Mike,

Lynne and I made it back to Jacksonville with no problem. We want to again express our appreciation to you for a fantastic visit.

Your selection of Mary for this award is, without doubt, one of the highlights of my career in medicine. I hope you realize how great we all feel it was.

Thanks again for all you did. I hope will cross again. With best wishes,

Sincerely yours,

Alvin H. Felman, M.D.

Professor Radiology

Pediatrics

AHF/at

Women Pioneers in Radiology: Mary Stuart Fisher, M.D.

Women Pioneers in Radiology: Mary Stuart Fisher, M.D.

Some readers may remember Dr. Mary Stuart Fisher as the recipient of the 1992 Marie Curie Award, honored for her contributions furthering the progress of women in radiology. Professor Emeritus in the Department of Diagnostic Imaging at Temple University, she continues to work part-time, teaching students and physicians as she has done for the past 43 years. Dr. Fisher reflects on her life in radiology in a recent interview with Focus contributor Kelly Mc Aleese.

KM: Why did you go into medicine?

MSF: I really wanted to be a research biologist, but my father, who was an obstetrician, said I didn’t have the skills for that field and recommended medicine instead. Possibly because I grew up during the Depression, he always insisted I’d have to be able to earn a living. I applied to medical school during World War II when there were few male applicants, which allowed more women (entry) for a brief period.

KM: Why did you choose radiology as a career?

MSF: My husband-to-be talked me into it, but I didn’t know beans about radiology at the time. It’s funny because I consider myself a feminist of sorts, but I’ve made a lot of decisions because all these men in my life told me to do it.

KM: What other role models did you have?

MSF: Ross Golden (Goldens Text) and Lois Collins during my radiology residency at Columbia Presbyterian. Some people say that my style of teaching is very similar to hers (Collins)...and of course George Wohl, my first boss.

KM: Where did you do your training?

MSF: I started at Columbia and was married after my first year (of training). My husband was working in Bethesda at the time (during the Korean War), so I commuted two hours each way every day for about a year. I was pregnant during the time, and the train conductor became noticeably more worried each month I was more pregnant. I finally moved to Washington, D.C., where I completed my training at Grover, Christie and Merritt. We moved back to Philadelphia. Because I had done a mixed internship, I couldn’t get a license to work in Philadelphia (as) I didn’t have training in obstetrics which was required at that time to practice. I was delighted to be offered a position at the VA (hospital), where a Pennsylvania license was not required. I stayed in Philadelphia at the Philadelphia General Hospital until it closed, at which time I was functioning as the de facto chairman.

KM: What do you like about radiology?

MSF: I loved radiology from the start! It’s so much fun, functioning as a consultant, being the “heart of the hospital,†having your finger on all of the clinical pulses. I started doing everything (in radiology) 20 years ago, but have since concentrated (where I was most needed) in the areas of chest, bone, and mammography.

KM: How did you become interested in teaching medical students and residents?

MSF: Well, I didn’t really have a choice at first. During my first job at the VA, my chairman assigned me to teach the students. Now, I enjoy teaching a great deal. I enjoy the enthusiasm and the information.

KM: What information?

MSF: The senior medical students know all sorts of things I don’t. They teach me a lot and keep me from slipping into an “intellectual rutâ€.

KM: What is your greatest achievement in radiology?

MSF: That’s easy, winning the Golden Apple Award for Teaching at Temple. (For the record, Dr. Fisher has had numerous other honors, including Fellowship in the American College of Radiology. She is also the past president of the Philadelphia Roentgen Ray Society.)

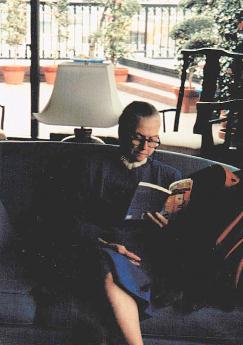

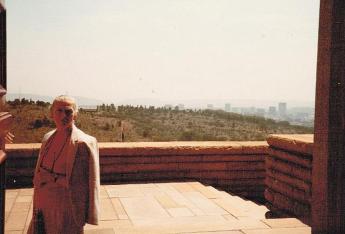

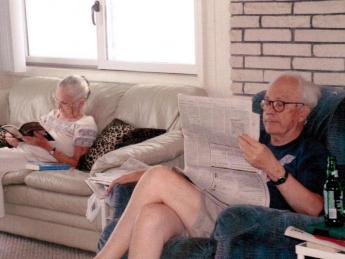

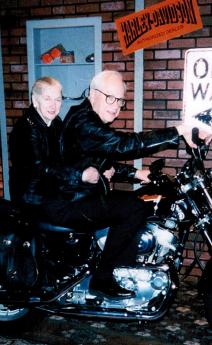

Dr. Fisher has an active personal life, as well as a busy professional career. The mother of four children and grandmother of eight, she and her husband enjoy music, reading and traveling when they can find the time in their busy schedules.

The author expresses her appreciation to Dr. Fisher for her insight into the life of a women pioneer in the field of radiology.

Computers and the Regulation of Medicine.

Computers and the Regulation of Medicine.

George Ross Fisher, M.D.

I am going to take chance in this essay that I can hold the attention of the reader through a preamble of theory, before addressing the consequences for the practice of medicine. That seems necessary because I believe that the consequences are different from what most readers would intuitively expect and persuasion lies in first convincing the reader of the theory.

CLOSED AND OPEN SYSTEMS

There is a growing body of endeavor known as the Theory of System, which acknowledge that all events are consequences of pre-existing conditions (like the consequences of adding acid to bicarbonate in a beaker), and are thus “closed†systems. However, most events in biology and sociology are so complex that it is only possible to deal with them as “open†system, for which we substitute wisdom for scientific certainty. “Wisdom†is a set of traditions, maxims, opinions, and strategies which allow you to make predictions about the inevitable outcome of events within an open system. The teleological nature of human events was once referred to as Manifest Destiny, and realists like Talleyrand spoke of diplomacy as the art of manipulating the inevitable.

Example:

Wisdom has it that in your choice of a practice location, you should remember that “you can’t make money where it ain’t.â€

And now a conclusion about the computer revolution: Since computers increase the capacity to store and manipulate detail, the computer revolution increases the number of closed systems, and shifts the scope of wisdom in decision-making from traditional areas to new subject which was formerly incomprehensible.

HIERARCHIES

In dealing with open systems, managers and executives have evolved a basic strategy; they organize manageable subunits into hierarchies. Units are organized within departments, then organized within divisions, reporting to a policy-making body. Further, because the purpose of the organizational structure is to simplify management, each level of the hierarchy is oblivious to the techniques of the level below, and is only interested in the output of the level below.

Example:

The patient paying his bill is interested in the total amount that he has to write on the “bottom line,†which in his case is the dollar amount of the check he must write

The director of the x-ray department is concerned with a subtotal related to the x-ray department. The chief technician is concerned with individual studies. The dark-room attendant is only interested in pieces of film.

COMPUTER CONCLUSION: Primitive Computer Systems merely duplicate the pre-existing manual system. Their real power lies in the next step, which is to reorganize the reporting system. That is, they cause a reorganization of the hierarchy.

TRANSMISSION

The prediction is made that management system will be forced in the direction of a hierarchy of three: Those who are able to make decisions, those who cannot make decisions but are necessary for some task, and the computer. One function often seen in non-computer systems is simply to pass the information unchanged up to the line. There is little doubt this activity will vanish.

Example:

Robert McNamara (from Princeton via Ford Motors) was a computer expert who became Secretary of Defense under John Kennedy. By installing computers, McNamara was able to jump the Army reporting system (Sergeant to Captain to Secretary of Defense) and confront the generals with discoveries before the generals had received the news. We are told that the generals didn’t like it a bit. But can anyone doubt that Robert McNamara carefully filtered the data before h presented it to President Kennedy? The system of hierarchical reporting condenses the data to the next step up.

COMPUTER CONCLUSION: Many systems of management by delegation will soon be swept away by the computer revolution, and middle management will be the most threatened region. It will resist but it will lose.

MODIFICATION

Another function of delegated systems is to take raw information and reduce it to condensed form for the benefit of the next level upward. They do so by a process which is often a mystery to the next higher level, and hence a certain power is conferred on the lower subunit to modify the conclusion by modifying the system of manipulation. The method for controlling such activity is to produce a procedure manual which the next higher level must approve, but the inherent complexity which forced a delegated process to be created also obscures the power of the delegated subunit to modify the system.

COMPUTER CONCLUSION: Computer technology strictly defines and inflexibly follows defined procedures for steps in hierarchy. It thereby confers much stricter control power to the higher levels of hierarchy.

THE NEED TO KNOW

If for no better reason than to reduce programming costs, the computer process confers a new power to the lower levels of hierarchy. The higher level must now strictly define its reasons for asking for certain information. If it cannot demonstrate a need to know, it cannot justify the cost of knowing.

Example:

The PSRO, acting on behalf of the physician community, violently resists the inclusion of data elements in the reported tape sent to the Bureau of Quality Assurance. At the same time, it is anxious to acquire as much data as possible from units lower in the hierarchy, who in turn resist the process. It can be expected that this process will eventually settle out at roughly the best equilibrium for the community at large, although differing aggressiveness among the participants may cause temporary inequities. The weapons in the battle, which are at the disposal of the physicians are:

(1) Superior Claims on the decision-making process.

(2) The faith of the public in physicians as the most trustworthy custodians of their health privacy.

(3) A superior pool of talent, determination, and independent means committed to a vital issue.

COMPUTER CONCLUSION: If you have a good chance of being the winner in the reorganization of a hierarchy, it is better to participate to your utmost rather than hold back out of fear that someone else will be the winner, because only participants are winner.

NETWORK

We have spoken thus far of hierarchy as the only manageable approach to the complexity of open systems. A more general description would be “modularity†since modules can interact in a lateral direction as well as vertically. When they do, the result is a network of modules in three dimensions. Since computers increase the ability to cope with complexity, they increase the ability to work in three dimensions. Hierarchy is the last resort of manual management; just as three-dimensional chess is beyond the ability of people who are not even very expert at two-dimensional chess. In this sense, the computer revolution provides some hope for the American System, which presents hierarchy and naturally prefers networks when feasible. This is to some extent a philosophical preference and does not seem to be true of the Japanese social system, or the German mentality, or the Communist method. The natural American instinct for lateral equality is thus an ally in Medicine’s conflict with Government, but a hindrance when it encourages Nurse independence or unrealistic consumerism.

Whether lateral or vertical, the interaction of modules in a complex open system is the same: delegation of a method, the output from one module as the sole input to other modules, and resistance to the need to know.

COMPUTER CONCLUSION: The organization of modules into vertical hierarchies or horizontal networks is largely a political process, with three-dimensional networks as the last resort of compromise, and with strict vertical hierarchies as the last resort of inadequacy.

CONFIDENTIALITY

Complexity is itself a major defense of confidentiality; since computers reduce complexity, they also destroy the smoke screen. Computer System which stumbles ahead or is manipulated into breaches of confidentiality is certain to raise a great uproar about the need to know and the right to conceal. In the PSRO system, the issues balance between the duty of accountability and the patient’s right to privacy. When reduced to these terms the physician community has a clear advantage in the mind of the public, if the advantage can be effectively exploited. The latter can, however, be overturned by speedy pre-emption of the turf. it can be predicted that special pleaders will insist on accountability when all they really want is power and satisfaction of envy; it can fairly be predicted that some will weaken their claim to privacy by overextending its bounds.

Example: The system of peer review on Medicaid prescriptions in Pennsylvania has turned up a number of instances of patients who obtained multiple prescriptions for “controlled†drugs from multiple doctors, filled at multiple drug stores, probably for resale on the streets. When the doctors and pharmacists were notified, they were universally grateful and took steps to curtail the problem. However, the computer vendor learned of the problem (regardless of the fact that all reports are shredded after review) and persuaded the state government to institute a system of restricting problem patients to a single physician. It may now be impossible to dislodge this meat-ax reaction, in spite of the fact that the computer peer-review system is probably able to cope with the problem without invoking hierarchical power.

A Second Example: The United States Navy recently developed a system of computer protection so elaborate that they boasted of it in the newspapers. Two computer scientists read of it, and in a month’s, the time had broken into the system via telephone. The Navy was then agitated to read of its disarmament in other newspaper articles.

COMPUTER CONCLUSION: There is no present foreseeable technical method of protecting the confidentiality of computerized data, except by physical ownership and physical protection of the machine itself and all of its activity.

CONCLUSIONS

The most significant event in the Twentieth Century is the Computer Revolution, just as the Industrial Revolution was the major event of the Nineteenth Century. By the greatest good luck for medicine, the computer revolution is capable of solving the four major problems which now threaten the American Medical System.

1. THE FAILURE OF THE PRE-PAYMENT INSURANCE MECHANISM. The removal of cost restraints on the patient (and thus the provider) has had a predictable upward effect on costs. The overwhelmed system has reacted in a typical hierarchical manner: try to convert insurance companies into regulatory bodies, and if that fails, into rationing systems. The computer revolution (if we are agile) has the potential of drastically reducing the information costs which are now 40% of hospital and insurance company costs. It also has the ability to control utilization abuses, and expose power abuse to public decision.

2. THE VAST INCREASE IN PARAMEDICAL PERSONNEL. Middle management is most vulnerable to computer replacement, and middle management now costs 20% of the hospital dollar. Physicians in complex medical centers are most alarmed about this problem, which they can easily identify by comparing the hospital parking problem with what it was, twenty years ago. Surgeons are typically least concerned since their role at the center of procedures is least threatened by aspirants. But surgeons are hearing of “unnecessary†surgery, and even the small-town solo practitioner has to hire girls to fill out forms. The complexity of our system must be reduced, and computers can do it. The best way to thwart the claims of aspirants to power is to eliminate jobs.

3. THE EXPLOSION OF SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION. No one would wish to reduce the output of the research community, but ways must be found to organize and transmit the information without resort to fragmentation by sub-sub specialists. The computer is ideally suited to the problem. THE MALPRACTICE CRISIS. Physicians are uncomfortable with the idea that peer review may soon become entangled in the malpractice system, as indeed it inevitably will. The matter comes down to biting the bullet, armed with a statistic. Surely consent for an arteriogram is more threatening if it is couched as “you might lose your leg†than if you are told, “you have one chance in five thousand†of such an occurrence. Realistic insurance premiums can be set when the risks are defined. Juries can be provided with realistic statistics on normal risks and normal expectation of benefits.

Through all of these four problems runs a common theme: The cost of medical care. The PSRO seems to be the last best hope of curtailing the cost threat to medicine, and so the PSRO can be expected to be the vehicle for the computer revolution’s resolution of the issue. Senator Bennett probably had no idea of what he was doing, but he did it, and the problem is now our problem.

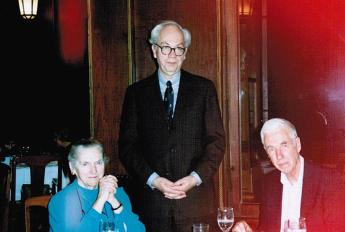

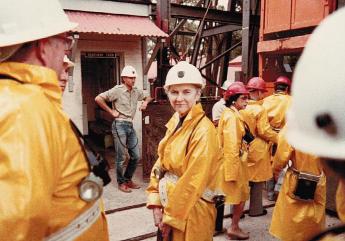

Mary Stuart Blakely Fisher, MD 1922-2006 Photos

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 Blogs

Mary Stuart Blakely Fisher, MD

First in any class.

Teacher, Mentor receives Marie Curie Award Decenber 3, 1992

New blog 2017-09-19 20:53:21 description

Radiology October 2006 In Memoriam

New blog 2017-09-20 18:59:26 description

Michael S. Huckman, M.D.Letter

New blog 2017-10-17 18:20:19 description

Letter from Radiology Associates Albert Einstein Medical Center

A letter from MSF's former resident.

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University / New York, N.Y Letter

New blog 2017-10-16 20:07:45 description

Temple University Letter: Christian R. and Mary F. Lindback Foundation award

New blog 2017-10-16 19:52:08 description

University Hospital of Jacksonville Letter

New blog 2017-10-16 19:59:27 description

Women Pioneers in Radiology: Mary Stuart Fisher, M.D.

New blog 2018-08-14 19:52:35 description

Computers and the Regulation of Medicine.

New blog 2018-08-22 20:03:03 description

Mary Stuart Blakely Fisher, MD 1922-2006 Photos

New blog 2017-07-26 20:20:33 description