2 Volumes

Revolutionary War Era

The shot heard 'round the world.

Romantics in Charge: Anti-Rules, Anti-Regulation, Anti-Control

The American Revolution

Houses of the Penn Family

|

| Jordan Meetinghouse |

The name Penn seems to be derived from the Welsh name for hill; hills are abundant in Wales. There is a reason to suppose the family was of royal descent. William's birthplace is now disputed, possibly in London near the Tower, possibly in Ireland at Sharry Estate, possibly the Church of All Hallows, Barking, England. Much better known and much-visited is Jordans, the place where he is buried in the simple buying ground of the Jordans Meeting House in Buckinghamshire, on a by-road running between Chalfont St. Peter and Beaconsfield. The present grave markers were added later since early Friends generally declined to have their names on tombstones. He lived most of his life and actually died in the family estate in Berkshire called Ruscombe where he had usually attended Friends Meeting in nearby Reading. At the time of his death, his fortunes were much reduced, having been betrayed by his steward Ford, and imprisoned for nine months.

|

| Slate Roof House |

When he lived in Philadelphia, William lived in the "Slate Roof House" on Second, between Chestnut and Walnut (a small park commemorates the building lot), and the Letitia Street House. His plans originally were to build a manor house where the Art Museum stands today, on Faire Mount, but somehow he changed his mind and moved to Pennsbury on the Delaware River near Trenton. This manor also did not survive, but its careful restoration is now well worth a visit.

|

| Horticultural Hall |

William Penn had thirteen children, a circumstance adding much difficulty for genealogists. John Penn, the nephew of William's son Thomas, was the grandson who acted as Proprietary Agent and Governor prior to the American Revolution, although Thomas remained in London as a close friend of the King, and exercised firm control of the policies of the Proprietorship. John built a fine mansion on the Schuylkill called Lansdowne at the site of what was to become Horticultural Hall in the 1876 Centennial. About all that can now be visited is the glen on the estate, over which a bridge is still usable. It was here that he was apprehended by Revolutionaries, and taken to house arrest in New Jersey.

|

| Solitude House |

Lansdowne burned in the early 19th Century and pictures of it are hard to find. A smaller house of John Penn's, called Solitude, still stands near what is now the Zoo. John was arrested by rebel troops while living at Lansdowne and held prisoner at another house confusingly called Solitude, on the grounds of what became Union Forge, later the Union Forge Ironworks, subsequently the Taylor Iron and Steel Company. All of this is located in High Bridge, New Jersey, where subsequently five generations of the Taylor family lived until 1938. The Union Forge Heritage Association/Solitude House Museum welcomes visitors.

|

| Stoke Mansion |

A different John Penn, who called himself John Penn of Stoke, inherited a much larger portion of the final payment for the Proprietorship lands in Pennsylvania in 1789 because he was the son rather than the nephew of Thomas Penn. Thomas had purchased the historic Manor House in Stoke Poges in England. Although this splendid palace dated back to 1066 and Elizabeth I had visited it, it was by 1790 so dilapidated that John Penn demolished three-quarters of it. In its place, he built a proper palace, called Stoke Park. The family fortunes seem to have declined after that, perhaps because of the extravagance of an estate he could not afford.

French Philadelphia

|

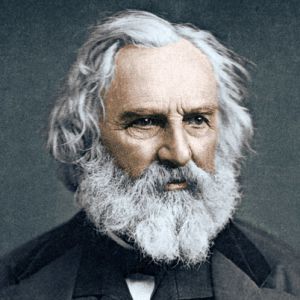

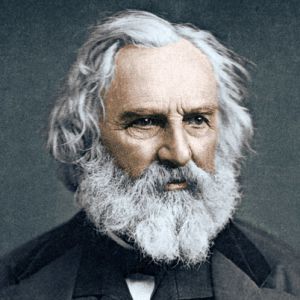

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow |

Since American relations with France are a little strained at the moment, it may not be completely welcome to hear it said that Philadelphia food is Creole. The reference is not to the several downtown French restaurants of outstanding quality, but to the two episodes when Philadelphia experienced waves of French immigration. The first of these was during the French and Indian War, when the Acadian French ("Cajun") were driven out of Nova Scotia, largely went to Louisiana and then were allowed to return. A lot of them stopped off in Philadelphia both going and coming. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow depicted, in his poem Evangeline, the tearful reunion of Evangeline and Gabriel in the hospital. And since for sixty years the Pennsylvania Hospital was the only hospital in the country, Longfellow had to put them here.

The second wave of French immigration was provoked by the guillotine in Paris, and the black revolution in French Haiti. Most people today are unaware that Talleyrand lived here, and LaRochefoucauld. The Duke of Orleans, future king of France, lived at 4th and Locust Streets, proposed to a (rich) Philadelphia lady, and was rejected by her father ("Sir, if you do not become king of France, you will be no match for her, and if you do become king, she will be no match for you.") Napoleon's brother Joseph lived at 9th and Spruce, and one of his marshals lived at 6th and Spruce. Really. Talleyrand had a deformed foot, and this somehow made him pals with Governor Morris who had a wooden leg. This friendship was part of the reason the Louisiana Purchase was possible, because they shared the favors of the same French lady, and had frequent occasion to meet. Both Franklin and Jefferson were ambassadors to France, it may be remembered, and for a while, Jefferson was quite a fan of the French Revolution, although the treatment of LaFayette by the French Revolutionaries did not exactly encourage that. The French treated Franklin like a God, but then so did Mozart and the King of England, and Franklin harbored many bitter memories of the French and Indian War all the while he was romancing the French into bankruptcy to pay for our revolution. The French refugees from Haiti brought Yellow Fever with them, and Dengue too, thus definitively terminating Philadelphia's hope of remaining the permanent capital of the nation.

It was during this Francophone period that Philadelphia cuisine acquired some characteristics which allow some food historians to call it Creole. Philadelphia Pepper Pot soup, for example, substituted tripe for terrapin. Those who know about these things say that many dishes now thought to be distinctly Philadelphian in fact had a French origin.

After the Convention:Hamilton and Madison

|

| Signers |

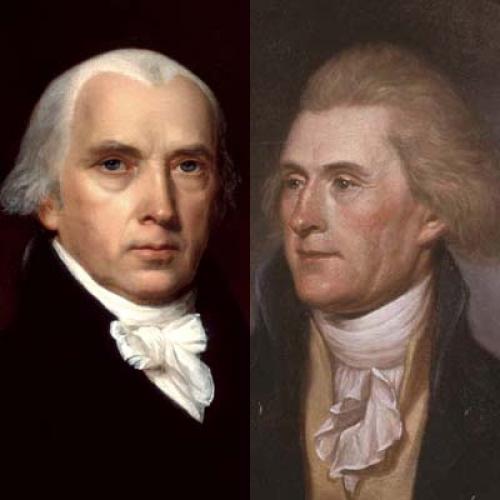

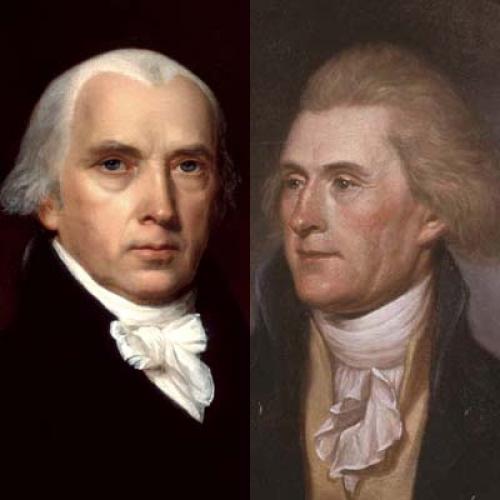

The Federalist Papers were written by three founding fathers after the Constitution had been completed and adopted by the Convention. Detecting hesitation in New York, the aim was for publication in New York newspapers to persuade that wavering State to ratify the proposal. It is natural that The Federalist was composed of arguments most persuasive to New York, putting less stress on matters of concern to other national regions. This narrow focus may explain the close cooperation of Hamilton and Madison, who must surely have suppressed some latent concerns in order to present a unified position. In view of how much emphasis the courts have placed on the original intent of almost every word in the Constitution, it seems a pity that no one has attempted to reconcile the words of the principal explanatory documents with the hostile disagreements of their two main authors, almost as soon as the Constitution came into action. Perhaps the psychological hangups would be more convincingly dissected by playwrights and poets, than historians.

John Jay wrote five of the essays, mostly concerned with foreign relations; his presence here highlights the historical likelihood that Jay might have been the one who first voiced the idea of replacing the Articles of Confederation. At least, he seems to have been first to carry the idea of a general convention for that purpose to George Washington (in a March 1786 letter). The remaining essays of The Federalist were written under the pen name of Publius by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, both of whom had a strong enough hand in crafting the Constitution, but who quickly became absolutely dominant figures in the two central political factions after the Constitution was actually in operation. And their eagerness to be central is itself telling. They were passing from a stage of pleasing George Washington with his favorite project, into furthering a platform for launching their own emerging agendas. It is true that Madison's Federalist essays were mainly concerned with relations between the several states, while Hamilton concentrated on the powers of the various branches of government. As matters evolved, Hamilton soon displayed a sharper focus on building a powerful nation; Madison scarcely looked beyond the strategies of internal political power except to see clearly that Hamilton was going to get in the way. These two areas are not necessarily incompatible. But it is nevertheless striking that two such relentlessly driven men could work together to achieve the same set of rules for the game they were about to play so unflinchingly. Thomas Jefferson had been in France during the Constitutional Convention. It was he who was most dissatisfied with the resulting concentration of power in the Executive Branch, but Madison eagerly became the most active agent for forming the anti-Federalist party, with all its hints that Washington was too senile to know the difference between a President and a King. Washington abruptly cut him off and never spoke to Madison after the drift of his opinions became undeniable. Today, it is common to slur politicians for pandering to lobbyists and special interests, but that presents only weak competition with the personal forces shaping leadership opinion, chief among them being loyalty to, and perceived disloyalty from, close political associates.

As a curious thing, both Hamilton and Madison were short and elfin, and both relied for influence heavily on their ability to influence the mind of

|

| George Washington |

George Washington, who projected the power and manner of a large formidable athlete. Washington had no strong inclination to run things and, once elected, no particular agenda except to preside in a way that would meet general approval. He had mainly wanted a new form of government so the country could defend itself, and pay its soldiers. Madison was a scholar of political history and a master manipulator of legislative bodies, while Hamilton's role was to supply practically unlimited administrative energy. Washington was good at positioning himself as the decider of everything important; somehow, everybody needed his approval. On the other hand, both Madison and Hamilton were immensely ambitious and needed Washington's approval. This system of puppy dogs bringing the Master a bone worked for a long while, and then it stopped working. Washington was very displeased.

The difference between these two short men immediately appeared in the way they chose a role to play. Madison the Virginian chose to dominate the legislative process as the leader of the largest state delegation within the

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

House of Representatives, in those days the dominant legislative chamber. Hamilton sought to be Secretary of the Treasury, in those days the largest and most powerful department of the executive branch. It's now a familiar pattern: one wanted to form policy through dominating the board of directors, while the manager wanted to run things his way, even if that led in a different direction. Both of them knew they were setting the pattern for the future, and each of them pushed his ideas as far as they would go. Essentially, this could go on until Washington roused himself.

After a short time in office, Hamilton wrote four historic papers about two general goals: a modern financial system, and a modern economy. For the first goal, he wanted a dominant national currency with mint to produce it and a bank to control it. Second, he also wanted the country to switch from an agricultural base to a manufacturing one. You could even say he really wanted only one thing, a national switch to manufacturing, with the necessary financial apparatus to support it. Essentially, Hamilton was the first influential American to recognize the power of the Industrial Revolution which began in England at much the same time as the American Revolution. Hamilton was swept up in dreams of its potential for America, and while puzzled -- as we continue to be today -- about some of its sources, became convinced that the secrets lay in the economic theories of

|

| David Hume |

David Hume and Adam Smith in Scotland, and of Necker in France. Impetuous Hamilton saw that Time was the essence of opportunity; we quickly needed to gather the war debts of the various states into the national treasury, we quickly needed a bank to hold them, and a mint to make more money quickly as liquidity was needed. It seemed childishly obvious to an impatient Hamilton that manufacturing had a larger profit margin than agricultural products did; it was obvious, absolutely obvious, that this approach would inspire huge wealth for the new nation.

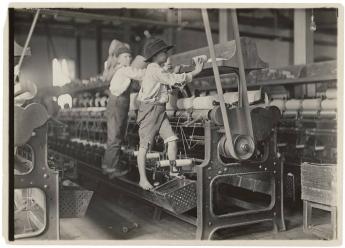

|

| Industrial Revolution |

Well, to someone like Madison who was incredulous that any gentleman would think manufacturing was a respectable way of life, what was truly obvious was that Hamilton must be grabbing control of the nation's money to put it all under his own control. He must want to be king; we had just got rid of kings. Furthermore, Hamilton was all over the place with schemes and deals; you can't trust such a person. In fact, it takes a schemer to know another schemer at sight, even when the nature of the scheme was unclear. Madison and Jefferson couldn't understand how anyone could look at the vast expanses of the open continent stretching to the Pacific without recognizing in this must lie the nation's true destiny. Why would you fiddle with pots and pans when with the same effort and daring you could rule a plantation and watch it bloom? If anyone had used modern business jargon like "Win, win strategy", the Virginian might well have snorted back, "When you say that to me, friend, smile."

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

|

| Dr. Thomas Cadwalader |

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed.

I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting.

"Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left.

Meschianza

|

| General Howe |

The British under General Howe occupied Philadelphia for a little more than six months, withdrawing at the end of May 1778. Washington and his starving troops were shivering in the miserable encampment at Valley Forge that winter, and it is easy to imagine the British encircling, besieging or storming the encampment to put an end to the war then and there. Instead, Howe settled down in the enemy capital and had a merry time of it. Historians differ about the reasons for this puzzling behavior. On the one hand, Howe never did any campaigning in the winter if he could help it, somehow feeling that gentlemen soldiers had a right to revel, just as school children now feel they have a right to loaf in the summer. Perhaps there were practical military reasons to avoid winter campaigns, as well. However, it is also true that Howe had shown whig sympathies in the past, and very likely did feel that conciliation with the colonists was not only a possible but the best possible outcome of the dispute. If that was his idea, he was listening too much to the rich Tories in Philadelphia and not enough to the scowling artisan class, or to the solemn-faced Quakers. All winter long, the British soldiers revealed in theatricals and parties, apparently oblivious to the starvation nearby, or the appalled reactions of the sober Quakers to music, dancing, and ornamental dress. If Howe had any purpose to bedazzle the populace, he could not have put a better man in charge than his Lieutenant-General Major John Andre, whose thumb-in-your-eye attitude was defiantly underlined by his taking up Benjamin Franklin's own house as his pied a Terre.

Andre certainly cut a fine figure. It would be hard to say whether John Burgoyne or John Andre was the most dashing man in England, but it was surely one or the other. They both wrote plays and poetry of professional quality, designed costumes and scenery, and organized one extravaganza after another. They were both handsome in the eyes of ladies, and fearless soldiers in the eyes of men. Anything you can do, I can do better.

About the time Howe was replaced by General Henry Clinton and recalled to England, the position in Philadelphia began to look dangerous for the British. The French signed an alliance with the American Revolutionists earlier that spring, and the concern became a real one that the French fleet might blockade the mouth of Delaware and trap the British Army, stranded a hundred miles upriver from its own Navy. When Andre learned they were leaving, he saw they needed to have a celebration that would be remembered.

|

| Benedict Arnold |

Even today, the day-and-night revelry is indeed remembered. Andre wrote a detailed description for his local girlfriend Peggy Chew (the daughter of Pennsylvania's Chief Justice) that is really something to read. Made all the more pointed with our present hindsight that Peggy Chew was the best friend of the Peggy Shippen who married Benedict Arnold, the letter gives the celebration a made-up name, Meschianza. Sometimes spelled Mischianza, the derivation is loosely connected to the Italian word for Medley. It began with a regatta of costumed soldiers and local ladies on barges sailing slowly down the river accompanied by cannon fire, singing, and music. The main events of the week took place on the South Philadelphia plantation of Joseph Wharton, now called 5th and Wharton Streets. Horsemen of the British Army put on a Medieval tournament with jousting and whatever, dressed in white and pink satin, and hats of pink silk with white feathers on the brim. There were fireworks at night and banquets. Good wine, toasts, and laughter to witty remarks. The final high point was a fancy dress ball. Wow.

And then, the British moved across the river to New Jersey, and were gone.

REFERENCES

| Treacherous Beauty: Peggy Shippen, the Woman behind Benedict Arnold's Plot to Betray America: Mark Jacob:978-0762773886 | Amazon |

5 Blogs

Houses of the Penn Family

Some idea of the social position of William Penn can be gathered from the houses of his family.

Some idea of the social position of William Penn can be gathered from the houses of his family.

French Philadelphia

The French and the English fought for centuries; colonies seeking independence played one against the other. Our cooking, clothing, and architecture went French when we favored France; traces of many periods still reflect that fact.

The French and the English fought for centuries; colonies seeking independence played one against the other. Our cooking, clothing, and architecture went French when we favored France; traces of many periods still reflect that fact.

After the Convention:Hamilton and Madison

Two of the main authors of the Federalist Papers -- and hence of the Constitution -- ultimately proved to be acting on entirely different sets of principles, aiming for widely different goals.

Two of the main authors of the Federalist Papers -- and hence of the Constitution -- ultimately proved to be acting on entirely different sets of principles, aiming for widely different goals.

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

Sometimes it's hard for others to understand what makes Quakers tick.

Sometimes it's hard for others to understand what makes Quakers tick.

Meschianza