0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

On Writing History

History doesn't write itself.

Rearranging Mickles, Makes Muckles

|

| Right Angle |

Thank you, Mr. President. Tonight I'm to discuss Right Angle Club's odd contribution to book publishing, with emphasis on history books. To make it easier for the audience to follow, I originally titled the speech Three Threes, for three meanings, in three categories each. It touched -- in threes -- on 1) book technology, 2) variable proportions of facts and opinion, and 3) pitfalls to success. Times three, made nine bases to touch, so that evening at the Philadelphia Club I had to hustle. For a reading audience, however, it's more comfortable to revert to the writing style which I am advocating, since it illustrates as it explains.

|

| Philadelphia-Reflections |

First, let's deconstruct the essay you are reading. Ten years ago, I began taking notes at the Right Angle Club's Friday lunches, writing reviews of the speakers. The younger generation calls it "blogging" when you then broadcast such essays on the Internet; that's how I started the journey, giving it the title of Philadelphia Reflections, which is reached by entering www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/topic/233.htm in the URL box of any search engine, on any browser. If you prefer, you can simply click on the underlined lettering in this blog, a process called "linking". The blogs in this website concentrate on the Philadelphia "Scene" because that's what our speakers usually do. Our club has met since 1922, so by rights, it might contain ten thousand blogs, but unfortunately, I arrived late, so we only have 3000. Call them 3000 beads in a bowl, subdivided into annual bowls of beads. After more accumulation, they were re-connected as Collections for ease of use in re-assembly. Sometimes they are chronological, sometimes by subject matter; the purpose is to expedite searching for things, placing them in temporary categories, ultimately producing a book, a speech, or an essay. When an archive grows to this size, it's surprising how easy it is to lose something you know you have written.

|

| The Right Angle Book |

After a while themes emerge, so if I picked similar beads from the combined bowl of four hundred, then groups of similar beads become necklaces. Just as green beads make a green necklace, blogs about Ben Franklin make up a Franklin topic. Selected but related necklaces can then be artfully arranged into a rope of necklaces, which is to say, a book about Philadelphia, from William Penn to Grace Kelly. Almost without realizing it, I had been writing quite a big book without foreseeing where it would go. I described this curiosity to my computer-savvy son, who wrote a computer program to make it simple for anyone to rearrange blogs and topics of aggregated material. Simple, that is, for an author re-arrange his random thoughts repeatedly, as if to wander among his own random thoughts, and only in retrospect extract the books. Most authors are not Scotsmen, but they eventually learn that Many a Mickle -- Makes a Muckle. Many authors, however, once imagined they sat down to write a book from start to finish, only to discover one was already there, waiting to emerge if the Mickles could be re-arranged. At the end of the process, it is of course often necessary to insert a few bridging sentences to smooth out the lumps. However, when this outcome hasn't been planned, most authors must totally rewrite their material into a coherent book, once they finally realize where it has been going. Since I am also in the publishing business in a small way, I was able to guide my son into automating several subsequent steps of conventional publishing so any author could perform them without a publisher.

That begins to make book authorship resemble fine art; the artist does it all except marketing. In marketing fine art, it is conventional for the artist to receive 50% of the retail price, whereas in book publishing an author only receives 10%, and must sell five books to achieve an equal result. With refinement, using this system of authorship promises to incentivize the writing of many superior books, in smaller individual numbers, but an overall greater reading audience. True, "file this program" also aspires to eliminate the whole old-fashioned assembly line of publishing, which is in the process of dying anyway, but without a useful replacement.

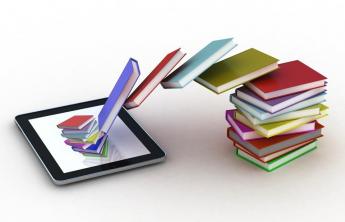

So here's the cluster of three components -- blogs re-assembled into topics, topics re-assembled into volumes, with copy editing, spell checking and book design mostly performed by the computer. Whether paper books will completely transform into e-books is not so certain, but will mainly depend on computer design, not book design. At the moment, e-books are making their greatest progress in fiction books, for technical reasons. No doubt their negligible production costs will promote the emergence of vanity publishing, works of transient interest, and otherwise unsalable books. For this to work, will require not merely a further computer revolution, but a revolution within information circles. I'm afraid I am too old to indulge in such distant visions and can only hope to advance it a stage or two.

Rossperry1

Rossperry4

1250Gulph

f166f166

Xy34Ty12

July 23,2017

LastPass--call George

More, or Fewer, Raisins in the Pudding

|

| manuscripts |

Some book publishers do indeed regard history as handfuls of paper in a manuscript package, mostly requiring rearrangement in order to be called a book. Librarians are more likely to see historical literature dividing into three layers of fact mingled with varying degrees of interpretation: starting with primary sources, which are documents allegedly describing pure facts. Scholars come into the library to pore over such documents and comment on them, usually to write scholarly books with commentary, called secondary sources . Unfortunately, many publishers reject anything which cannot be copyrighted or is otherwise unlikely to sell very well, however important historians say it may be. Authors of history who make a living on it tend to focus on the general reading public, generating tertiary sources, sometimes textbooks, sometimes "popularized" history in rising levels of distinction. Sometimes these authors go back to original sources, but much of their product is based on secondary sources, which are now much more reliable because of the influence of a German professor named Leopold von Ranke. Taken together, you have what it is traditional to say are the three levels of historical writings.

|

| Leopold von Ranke |

Leopold von Ranke formalized the system of documented (and footnoted) history about 1870, vastly improving the quality of history in circulation by insisting that nothing could be accepted as true unless based on primary documents. Von Ranke did in fact transform Nineteenth-century history from opinionated propaganda in which it had largely declined, into a renewed science. At its best, it aspired to return to Thucydides, with footnotes. That is, clear powerful writing, ultimately based on the observations of those who were actually present at the time. Unfortunately, Ranke also encased historians in a priesthood, worshipping piles of documents largely inaccessible to the public, often discouraging anyone without a PhD. from hazarding an opinion. The extra cost of printing twenty or thirty pages of bibliography per book is now a cost which modern publishing can ill afford, making modern scholarship a heavier task for the average graduate student because the depth of scholarship tends to be measured by the number of citations, but incidentally "turning off" the public about history. All that seems quite unnecessary since primary source links could be provided independently (and to everyone) on the Internet at negligible cost. And supplied not merely to the scholar, but to any interested reader, no need to labor through citations to get at documents in a locked archive.

|

| E-Books |

The general history reader remains content with tertiary overviews, and a few brilliant secondary ones because document fragility bars public access to primary papers, but many might enjoy reading primary sources if they were physically more available. The general reader also needs impartial lists of "suggested reading", instead of the "garlands of bids", as one wit describes the bibliographies employed by scholars. If you glance through the annual reports of the Right Angle Club, you will see I have increasingly included separate internet links to both secondary as well as primary sources, because the bibliographies within the secondaries lead back to the primaries. Unfortunately, you must fire up a computer to access these treasures. The day soon approaches when scholars can carry a portable computer with two screens, one displaying the historian's commentary while the second screen displays related source documents. It seems likely history on paper will persist while that remains cheaper, but also because e-books make it hard to jump around. Newspapers and magazines particularly encounter this obstacle, because publication deadlines give them less time for artful re-arrangement. E-books are sweeping the field in books of fiction because fiction is linear. Non-fiction wanders around, even though this subtlety is often unappreciated by computer designers.

Prisoners in the Stone

|

| A Prisoner of the Stone |

The first revolution in book authorship has already taken place. Almost all manuscripts arrive on the publisher's desk as products of a home computer. In fact, many publishers refuse to accept manuscripts in any other form. Not only does this eliminate a significant typing cost to the publisher, but it allows him to experiment with type fonts and book design as part of the decision to agree to publish the book. What's more, anyone who remembers the heaps of paper strewn about a typical editor's office knows what an improvement it can be, just to conquer the trash piles. To switch sides to the author's point of view, composing a book on a home computer has greatly facilitated the constant need for small revisions. An experienced author eventually learns to condense and revise the wording in his mind while he is still working on the first draft. However, even a novice author is now able to pause and select a more precise verb, eliminate repetition, tighten the prose. He can go ahead and type in the sloppy prose and then immediately improve it, word by word. The effect of this is to leave less for the copy editor to do, and to increase the likelihood the book will be accepted by the publisher. The author is more readily able to see how the book looks than he would have been with mere typescript.

It must be confessed, however, that a second revolution caused by the computer has already come -- and gone. Not so long ago, I once linked primary documents already on the Internet to the appropriate commentary within my blog. The idea was to let the reader flip back and forth to the primary sources if he liked, and without interrupting the flow of my supposedly elegant commentary. In those early days of enthusiasm, volunteers were eager to post source material into the ether, just asking for someone to read it eagerly. I had linked up Philadelphia Reflections to nearly a thousand citations when an invincible flaw exposed itself. Historians were eager enough to post source documents, but not so eager to maintain them. One link after another was dropped by its author, producing a broken link for everyone else. The Internet tried to locate something which wasn't there, slowing the postings to a pitiful speed. Reluctantly, I went through my web site, removing broken links and removing most links. Maybe linking was a good idea, but it didn't work. There is thus no choice but to look to institutional repositories for historical storage, and funding to pay for maintaining availability for linkage. It is not feasible to free-load, although only recently it had seemed to be.

This pratfall assumed technology would provide more short-cuts than in fact it would. A more difficult obstacle emerges after some thought given to the nature of writing history because it seems remarkably similar to Michelangelo's description of how to carve a statue. Asked how to carve, he said it was simple. "Just chip away the stone you don't want, and throw it away." Michelangelo saw statues as "prisoners of the stone" from which it was carved, while insights and generalizations of history emerge from a huge mass of unsorted primary documents. But there is a different edge to writing history. Uncomfortably often, the process of writing history is one of disregarding documents which fail to support a certain conclusion, often documents which send inconvenient messages to modern politics. Carried too far, de-selecting disagreeable documents amounts to attempting to destroy alternative viewpoints. By this view of it, what the author chooses to disregard, is then as important as what he chooses to include. Unless awkward linkages are consciously maintained in some form, they will soon enough disappear by themselves. It is a great fallacy to assume that ancient history can be isolated from current politics, or even to believe that history teaches the present. Often, it is just the other way around.

Dithering History

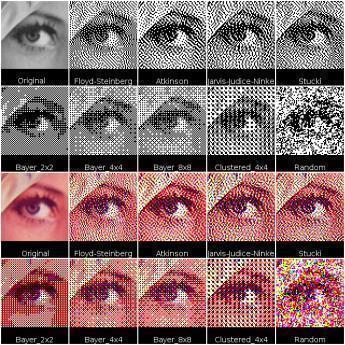

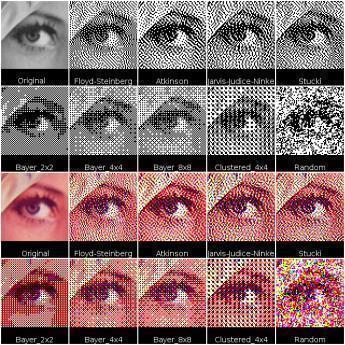

Dithering is originally a photographic term, referring to the process of smoothing out rough parts of an excessively enlarged photo. Carried over to the profession of writing history, the term alludes to smoothing over the rough parts of a narrative with a little unacknowledged conjecturing.

In photography, when a picture is enlarged too far, it breaks apart into bits and pieces. Dithering fills in the blank gaps between "pixels" actually recorded by the camera. It amounts to guessing what a blank space should look like, based on what surrounds its edges. In the popular comic strip, Blondie's husband Dagwood works for an explosive boss called Mr. Dithers, who "dithers" between outbursts, when he vents his frustration. But that's to dither in the Fifteenth-century non-technical sense, meaning to hesitate in an aimless trembling way. If the cartoonist who draws Blondie will forgive me, I have just dithered in the sense I am discussing in history. I haven't the faintest idea what the cartoonist intended by giving his character the name of Mr. Dithers, so I invented a plausible theory out of what I do know. That's what I mean by a third new meaning for either, in the sense of "plausible but wholly invented". It's fairly common practice, and it is one of the things which Leopold von Ranke's insistence on historical documentation has greatly reduced.

To digress briefly about photographic dithering, the undithered product is of degraded quality, to begin with. Dithering systematically removes the jagged digital edge, and restores the original analog signal. In that case, dithering the result brings it back toward the original picture. That's not cheating, it's the removal of a flaw.

Dithering of history comes closer to resembling a different photographic process, which samples the good neighboring pixels on all sides of a hole and synthesizes an average of them to cover the hole. It works best with four-color graphics, converting them to 256-color approximations. But the key to all photographic approaches is to apply the same formula to all pixel holes. That's something a computer can do but a historian can't, and historical touch-ups seem less legitimate because the reader can't recognize when it has happened, can't reverse it by adding or removing a filter. Dithering may somewhat improve the readability of the history product occasionally, usually at the expense of inaccuracy, sometimes large inaccuracy. It's conventional among more conscientious writers to signal what has happened by signaling, "As we can readily imagine Aaron Burr saying to Alexander Hamilton just before he shot him." That's less misleading than just saying "Burr shouted at Hamilton, just before he blew his brains out." The latter sends no signal or footnote to the reader, except perhaps to one who knows that Hamilton was shot in the pelvis, not the head. In small doses, dithering may harmlessly smooth out a narrative. But there's a better approach, to write history in short blogs of what is provable, later assembling the blogs like beads in a necklace. Bridges may well need to be added to smooth out the lumps, but that becomes a late editorial step, consciously applied with care. And consequently, author commentary is more likely to recognized as commentary, rather than rejected as fiction.

Dithering the holes is often just padding. It would be better to spend the time doing more research.

History Writing and History Teaching

The conventional pattern of testing history students sounds a lot like the pattern of writing history. Daily or weekly quizzes, followed by tests at the end of subject material, followed in turn by final examinations of a whole course; it all sounds like blogs for events, chapters for topics, and books for an overall subject, as we have earlier proposed as the pattern for publishing history. It would probably be an endless argument as to whether teaching is patterned after authorship or the other way around since nowadays most books of history are written by professors who are paid to teach. Furthermore, every lecturer quickly learns how organizing a lecture and responding to questions will sharpen the insights of authorship. Those who pursue two trades simultaneously will usually adopt similar patterns for both, regardless of which is the primary source of income.

There is one difference, however. Ever since von Ranke made footnotes and primary source material the essential hallmarks of historical scholarship, academic history has acquired a certain rigor which talking to an audience of late teenagers does not encourage, may even discourage. Professors with long hair and blue jeans are attempting to merge with the audience, and those who promote them are wise to withhold tenure until it is established that standards are being met, particularly in grade inflation. There is even an undercurrent to the repeated complaint that publication is being overvalued by comparison with teaching skill. In an unmonitored classroom, it can be difficult to know whether presentations are politically neutral, fact-based and restrained. Publications and citations can at least be judged by those standards. But that may be the least of it.

|

| Thucydides and Machiavelli |

History to a large extent is based on secondary and tertiary sources, and what the student retains is a summation of filtered interpretations. From what the students learn, the culture learns, possibly filtered again by graduates who have become columnists and anchormen. Professors are a vital link in society's chain of opinion formation, eventually reaching the politician who raises his hand to vote in a legislative body. Whether that politician is responding to the myth of George Washington and the cherry tree or to the generalizations of Thucydides and Machiavelli -- makes a difference, even though George Washington makes a better role model than Machiavelli. The point is that academic lectures cannot easily employ footnotes to primary sources, as secondary sources regularly are expected to do. And they are only one example of several sources of community opinion which could profit from lessening the doubts of their critics.

REFERENCES

| Political Theory Classic and Contemporary Readings, Vol. 1: Thucydides to Machiavelli: Joseph Losco (Editor), Leonard A. Williams (Editor): ISBN: 978-1891487910 | Amazon |

Quakers and Idolatry

|

| Philadelphia's Quaker Meetinghouse |

There are about forty thousand bodies buried in Philadelphia's Quaker Meetinghouse grounds at Fourth and Arch Streets, which contain only two tombstones. The yellow fever epidemics of the era account for much of that, but it's nevertheless a striking portrayal of early Quaker aversion to anything resembling idolatry. It underlines this attitude by sharp contrast with more recent uproars about desecrating statues of Confederate generals in public spaces of the Old South, which even Robert E. Lee objected to constructing. They led plausibly to erecting and then defacing Union generals in Northern states as well; since it seemed natural for statue-desecration to evolve into an equal-opportunity demonstrations. A little primitive perhaps, but even-handed.

|

| The Fourth Crusade |

Worshiping graven images has a long history. You needn't be a public-statue expert to remember the terracotta Chinese soldiers are two thousand years old, and the Egyptian pyramids are even older. The chariot horses over the Brandenburg Gate make a stronger illustration of the idea, intertwined over the shorter length of Western civilization. Although carvings might be older, we also have a reasonably accurate history of the bronze statues of these horses. The technique evolved with different proportions of copper and tin, with other metals sometimes added, but the underlying idea is to make a hollow bronze statue, giving the appearance of a much heavier solid bronze one, apparently originating in the Greek islands off the coast of Turkey in the second Century. There were in fact two such statues, with different subsequent histories. The Fourth Crusade was the one where Western European Christian Crusaders invaded Constantinople the main eastern Christian capital, never getting to the Holy Land. Even if they started with good intentions, Christians were content to carry off Christian booty, including the bronze horses. One set was sent to Venice and the other set got to the Christians in Southern France.

|

| Frederick the Great |

Frederick the Great put one set in the center of Berlin. In time, Napoleon took both statues to Paris, but later returned them. The one in Berlin, or perhaps copies of it eventually came to symbolize Nazi Germany, but later Checkpoint Charlie. The details of these conquests and adventures are not not of much consequence today, leaving only the central point that someone conquered someone else, and God must love the victor. The main point became victory, dogmas have been forgotten. Only the Quakers seem to be willing to mention another main point: Thousands of people died for these statues, but very few tourists could now tell you why. The Quakers reached a conclusion we might reconsider. Pulverize all statues and churches, thus saving the world from future grief. Since the Quakers also were first to free the slaves but later mostly disapproved of the Civil War, the irony was not lost on them. But most of their grandchildren reversed the assessment. It's too early to say how another generation will be persuaded to feel.

|

| General Lucius Clay |

During the War against Nazi Germany, my uncle was General Lucius Clay's room-mate, and the two of them were appointed to oversee de-Nazification of the defeated Germans by a third Pennsylvania Dutchman, Dwight Eisenhower. The concept was devised by Henry Morgenthau, then Secretary of the Treasury, in a famous letter urging a program to make Germany into an agricultural nation "for a thousand years". Accordingly, my father's brother oversaw the public burning of tons of postage stamps containing swastikas, plus every photograph of Adolph Hitler the Army could locate, along with similar symbols of the Third Reich. Nearly eighty years have passed since then -- essentially two generations, but it still remains illegal to possess such documents. Evidently, a sense of vengefulness so regularly outlasts its provocation, that passing the grievance on to children is usually hard to justify.

6 Blogs

Rearranging Mickles, Makes Muckles

Many a mickle, makes a muckle. Re-arranging the mickles makes better buckles.

Many a mickle, makes a muckle. Re-arranging the mickles makes better buckles.

More, or Fewer, Raisins in the Pudding

The primary sources of history are supposed to be factual. Tertiary history is mostly an interpretation of many primary bits.

The primary sources of history are supposed to be factual. Tertiary history is mostly an interpretation of many primary bits.

Prisoners in the Stone

History emerges from a welter of facts, with the irrelevant and inconvenient material selectively removed.

History emerges from a welter of facts, with the irrelevant and inconvenient material selectively removed.

Dithering History

It's better to start writing history with what you know for certain. And it's usually better to stop there, too.

It's better to start writing history with what you know for certain. And it's usually better to stop there, too.

History Writing and History Teaching

Teaching history is remarkably similar to writing history, at least in its pattern of construction. But there is one exception.

Teaching history is remarkably similar to writing history, at least in its pattern of construction. But there is one exception.

Quakers and Idolatry

Early Quakers were so opposed to idolatry, they wouldn"t allow tombstones.

Early Quakers were so opposed to idolatry, they wouldn"t allow tombstones.