4 Volumes

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Reminiscences, In Memoriam, The Right Angle Club,

Philadelphia doesn't toot its own horn very much. A central part of its charm is the wealth of anecdotes, and many charming characters, known only to insiders. You have to be a real Philadelphian to know very much of this lore.

Philadelphia Reminiscences

Volume of Philadelphia Historical Episodes

In Memoriam

Charles Peterson

Lewis B, Flinn, M.D.Wilton A. Doane,MD

Henry Cadbury

Martin Orne, MD, PhDGeorge W. Gowen, MD

Kenneth Gordon, MD

Mary Stuart Fisher, MDOrville P. Horwitz,MD

Lewis Harlow van Dusen, Jr.

Hobart Reiman, MD.

Lindley B. Reagan, M.D.

Allan v. Heely

Frederick Mason Jones, Jr.

Russell Roth,MD

George Willoughby

Earle B. Twitchell

Jonathan Evans Rhoads, Sr.

Garfield G. Duncan,MD

Hastings Griffin

Joseph P. Nicholson

Howard LewisAl DriscollHenry Bockus, MD

Mary Dunn

William H. Taylor

Abraham Rosenthal

Charles Peterson and Amity Buttons

|

| Charles Peterson |

Charles Peterson, the famous architectural historian and preservationist, died just before his 98th birthday on August 19, 2004. It is to him we largely owe the redevelopment of Society Hill, and the design of the Independence National Park, as well as a host of restorations from the Adams Mansion of Quincy, Massachusetts, to the early French settlements along the Mississippi. He conceived of many national historic preservation projects, the most notable of which is the Historic American Buildings Survey (HASB) of the Department of the Interior.

|

| The Adams Mansion |

While he was most notable for large visions and huge projects, he also had a keen appreciation for fastidious accuracy in small matters, of which the Amity Button would be a vivid example. In the surviving Colonial buildings of Philadelphia, it is common to find a plain ivory coat button nailed to the top of the newel post of the main staircase. There's one in Independence Hall, another in the grand staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, and there is one in Charlie Peterson's own home, the one where he was the first Society Hill gentrification pioneer, a house originally built by Stephen Girard around 3rd and Spruce.

|

|

The Free Quaker Meeting House |

There is a strong tradition in Philadelphia that these strange buttons are Amity Buttons, nailed there by the Quaker builder at the moment when the new owner had fully settled his construction debt, symbolizing the amity between a willing buyer and a willing seller. Countless visitors to Society Hill have been shown these curious buttons, and it always seems to produce a warm glow of appreciation for the discovery. If you have one of these in your own house, you can be very proud.

Unfortunately, Charlie Peterson couldn't find any evidence for the truth of this fable, and you can be sure he subjected the matter to a totally dedicated search. You might think there would be some notations in the deeds, or in the correspondence of the day, or in the literature of the times. You would think that someone who repeats this tale would be able to relate where he got it, and that would lead to some letters in an attic, and that if you work hard enough, you will find it. But when the button matter came up, Mr. Peterson would suddenly become grim-lipped and sad, and repeat the mantra that there is no evidence to support the story. He even awarded prizes to architectural students for essays on newel posts, banisters, and stair rails, but no student essay ever turned up any authentication of the Amity Button story. Absence of evidence is of course not the same as evidence of absence, so it is remotely possible that the story will someday be vindicated.

Indeed, you have to believe there was something or other to start the story. Victor Failmetzger and his wife, who have a notable reputation for authenticating old house parts, relate that in Colonial Virginia it was common to have hollow newel posts on the stairway, and occasionally to find the deed to the house secreted in one of them. So the search goes on.

In fact, it always seemed likely that Charles Peterson very much wanted to believe the fable was true. But until some evidence turned up, he was going to go to his grave with the declaration that there existed no evidence for it.

Henry Cadbury Dresses Up for the King

|

| Henry Cadbury |

There are a few old Quaker Clothes in the attics of their descendants, and on suitable occasions, an old broad-brimmed hat or two will appear at a Quaker gathering, for amusement. Quakers gave up the old style of "plain dress" when it became generally agreed that such eccentric dress was not plain at all but rather drew attention to itself. On the other hand, there is a distinctly unfashionable quality to almost everything Quakers do wear. When silk and nylon stockings were fashionable for women, Quaker women often wore black stockings. When it became the style for women to sport black stockings, Quaker women usually wore flesh-colored nylons. Among men, thin metal-trimmed spectacles displayed the same counter-fashionable tendency. Nowadays, these little quirks are often public signals among strangers, a way of wig-wagging "I notice you are a Quaker, so am I." And of course, unfashionable clothes are cheaper, and that's always a good thing.

And so it happened in 1947 that the Quakers were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, with information passed along that white tie and tails were the expected form of dress at the ceremony. Henry Cadbury was selected to receive the award on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, and you can be sure Henry Cadbury didn't own a set of tails. Henry was also very certain he wasn't going to go out and buy a set, just for a single wearing.

The AFSC collects used clothing, to distribute to the poor. Henry inquired whether there might be a set of white tie and tails to be found in the used-clothing bin, and luckily there was. It had been collected on behalf of the Budapest Symphony Orchestra when that impoverished but distinguished group of musicians was invited to give a concert in London. One of the monkey suits more, or less, fit Henry.

So, after investing in dry cleaning and pressing, Henry packed it up and went off to Oslo, to meet the King.

Kenneth Gordon, MD, Hero of Valley Forge

|

| Valley Forge |

There's no statue of Ken Gordon at Valley Forge National Park, although it would be appropriate. No building is named after him; it's probable he isn't even eligible to be buried there. But there would be no park to visit at Valley Forge without his strenuous exertions.

One day, Ken's seventh-grade daughter came home from school with the news that the father of one of her classmates said that Valley Forge Park was going to be turned into a high-rise development. That's known as hearsay, and lots of things you hear in seventh grade are best ignored. But this happened to be substantially true. At that time, the Park was owned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and Governor Shapp was finding the upkeep on the Park was an expense he needed to reduce. The historic area had two components, the headquarters area, and the encampment area. One part would become high-rise development and the other would become a Veteran's Administration cemetery. Although any form of rezoning has the familiar sound of politics to it, Dr. Gordon (a child psychiatrist) had the impression that Sharp was mostly interested in reducing state expenses, and had no particular objection to some better use of the historic area. At any rate, when Gordon went to see him, he said that he would agree to a historic park if Gordon could raise the money somehow. The Federal Government seemed a likely place to start.

Well, the sympathetic civil servants at the National Park Service told him how it was going to be. You get the consent of the local Congressman (Dick Schulze) and it will happen. If you don't get his consent, it won't happen. It seemed a simple thing to visit that Congressman, persuade him of the value of the idea, and it would be all done; who could refuse? After the manner of politicians, Schulze never did refuse, but somehow never got around to agreeing, either. It takes a little time to learn the political game, but after a reasonable time, the National Park employees told Gordon he was licked. Too bad, give up.

He didn't give up, he went to see his Senators, at that time Scott and Clark. They instantly thought it was a splendid idea, and instead of going pleasantly limp, they sent Citizen Gordon over to see Senator Johnson of Louisiana, the chairman of a relevant committee. Johnson also thought it was a great idea, and called out, "Get me a bill writer!" A bill writer is usually a government lawyer, tasked with listening to some citizen's idea and translating it into that strange language of laws -- section 8(34), sub-chapter X is hereby changed to, et cetera. Bill writers have to be pretty good at it, or otherwise, they will misunderstand the intent of the original idea, modified by the personal spin of the committee chairman, the comments of the authorizing committee, and later bargains struck in the House-Senate conference committee. Having negotiated all those hurdles, a bill has to be written in such a prescribed manner that it won't be found to have multiple loopholes when it later reaches the courts in a dispute. A good deal of the time of our courts is taken up with making sense of some careless wording by bill writers. That's what is known as the "Intent of Congress", an ingredient that may or may not survive the whole process.

|

| Dick Schulze |

Ken Gordon had to go through this process, including testimony at hearings, for three separate congressional committees. To get everybody's attention, he organized several hundred supporters to write letters and get petitions signed by several thousand voters. These supporters, in turn, influenced the media and started a lot of what is known as buzz. All of this is an awful lot of work, but there is one thing about this case that can make us all proud. Not once did a politician suggest a campaign contribution was essential in this matter.

In time, ownership of the Park did in fact migrate from the Commonwealth to the U.S. Department of the Interior, hence to the National Parks Service. Everyone agrees it has been well managed, and increasing droves of visitors come here every year. It is now clearly a national treasure. Unfortunately, the encampment area got away and has been commercially developed, although not nearly as high-rise as originally contemplated. Along the way, many discouraging words were spoken about the futility of fighting against such odds. The outcome, however, is the embodiment of two slogans, the first by Ronald Reagan. "It's amazing what can be accomplished, if you don't care who gets the credit for it." The other slogan is older, and Quaker. All you need, to accomplish anything, is leadership. And leadership -- is one person.

One day Ken Gordon, the very busy doctor, was asked how much of his time was taken by this effort. His answer was, ten hours a week, every week for five years.

Lewis Harlow van Dusen, Jr. (1910-2004)

|

| Croix de Guerre |

Lew van Dusen was one of the great story-tellers of a story-telling city. In one continuous lunch conversation he could string together personal anecdotes about Lloyd George, Lawrence of Arabia, William Bingham, the making of the hydrogen bomb, the Croix de Guerre (which he had been awarded), Nicholas Murray Butler, several Supreme Court Justices, Harvard Law School (where he led the class), and on and on until the waitress would just go ahead and clear the table. He even told of his own great suffering as a boy sitting at proper Philadelphia dinners, where it was a firm rule that acceptable topics of conversation were limited to the Wimbledon lawn tennis matches and the sinking of the Titanic.

When the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case of State Oil v. Kahn came up for arguments, he and I rode together on the Metroliner down to Washington, stayed at a club there, and after the hearing took the train back to Philadelphia. During the entire time, Lew never stopped talking, and his voice was very loud. There was the time in Macao when a retired British diplomat came up to him and said he knew the history of every gravestone in the cemetery for foreigners, except five, and two of those names were on the letterhead of Lew's firm (Drinker, Biddle and Reath). Drinker, it turns out, was American consul and discovered that all of his guests were poisoned by the cook. He traveled all night, getting stomachs pumped out, but not his own, and died the next morning from the poison. Biddle, on the other hand, was also a physician interested in Yellow Fever and died of it when he contracted the disease from one of the subjects.

There was the time when he was the young guest of Nicholas Murray Butler at a luncheon with British Prime Minister Lloyd George. "Tell Mr. Roosevelt," said George, "That Social Security is nothing but a dole."

And the time when King George gave everybody the day off on his 25th Anniversary as King, so they played cricket. His teammate was Lawrence of Arabia, and after the game, Lawrence hopped on his motorcycle and rode off down the road to be killed. Lew was the last person to see Lawrence alive.

Well, when you get to the Supreme Court, the public stands in line on the steps, out in the rain. But the lawyers go around to the back door, where there are a lounge and a lunchroom. Inside two minutes, Lew was surrounded by lawyers as he told more stories. One of them tugged my sleeve and asked, "Is that who I think it is?" I said I supposed so, although who he had in mind is still a mystery to me.

State Oil turns out to have been as important to antitrust law as we supposed it would be; the fine points of vertical integration were afterward explained to me. And finally, I was told how, when he was chairman of the Ethics committee of the American Bar Association, Lew's committee caused the ABA to reverse its long-standing opposition to cameras and audio equipment in courtrooms. The effect of this has been slow, but gradually courts are permitting the televising of trials, and eventually they probably all will permit it. But not yet the U.S. Supreme Court. Non-lawyers still stand in the rain outside, and if there are no seats left inside, too bad.

Lin

Lindley B. Reagan, M.D.

July 16, 1918 -- September 10, 1995

|

| Lindley B. Reagan, M.D |

The first and oldest hospital in America, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce Streets, always had a strong Quaker flavor but a unique medical tradition as well. Since it was the only American hospital for decades, later becoming the home hospital of the first medical school in the country, it impressed its ideals and traditions on the whole of American medicine. However, it imposed so many difficult demands on its trainees that a century or more of an evolving profession simply moved away from copying it. It was, in 1960, the last hospital in the country to begin paying its resident physicians anything at all, one of the last privately controlled American hospital to adopt a billing and accounting department, and one of the last if not the last to regard a handful of private beds as merely a convenience for the patients of the staff physicians. In 1970 its method of maintaining inventory was to notice that the supplies on the shelf were running low, and ordering some more. It was founded in Benjamin Franklin's words, for the "sick poor, and if there is room, for those who can pay," and could only survive into the late 20th Century through private donations and the freely contributed services of the doctors, student nurses and administration. No amount of money could induce people to work as hard as they worked. You might say this was the only aspect of Medieval monasteries which Philadelphia Quakers thought worthy of imitating.

Somewhere in this set of ideas was the treasured concept of a rotating internship, preferably two years long, prior to entering specialty training through a residency. In 19th Century Vienna, it was a matter of rule that an intern was just that, physically confined within the walls for the term of service, and a resident was just that, someone who lived on the campus. The Pennsylvania Hospital had no such rule, but since it paid the doctors nothing for five or six years of eighty-hour weeks, their poverty forced them to satisfy the Viennese rules by default. Entertainment was bridge or poker in the intern quarters, conversational chit-chat was a description of bizarre cases or peculiar patients, a weekend "off-call" was a good time to catch up on correspondence. There were student nurses around, of course, but the matron was a pretty no-nonsense chaperon. Every class of interns contained one or two millionaires by inheritance, but peer pressure made them nearly indistinguishable in the daily routines. Aristocrats' main value to the resident physician community was their access to the ruling families in the city, and hence to the governance of the hospital, in case governance should occasionally abuse the vulnerability of the trainees.

I find in retirement that most of my colleagues are now willing to tell stories of the "old days" which they were unwilling to tell at the time. Over several glasses of the finest single-malt in a walnut-paneled club, one such story recently surfaced. It concerned Lin.

Lin was a member of an old Quaker family, surprising everybody during the Second World War by volunteering as a junior physician in the Navy. He was assigned to a marine regiment in the Pacific Theater and went through some of the most murderous fightings on Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. Our grapevine reported that the enlisted Marines in his outfit absolutely worshipped him, and I easily believe there was a lot of quiet heroism behind that gossip. He told me he had decided to become an internist while in the Pacific, but somehow only a surgical residency was available when the War was over, so he took it. He was probably the best internist on the staff, and it showed in his conduct of surgery, where it sometimes matters more what you decide to cut than what you cut. He always looked exhausted, but never hesitated to drive himself another hour when the situation demanded it. One day, he had to excuse himself from an operation, an almost unheard-of event, and testing his own urine, found it loaded with sugar. So, the soft-spoken Quaker internist who was primarily doing surgery had to add the burden of insulin injections to his load. If he ever complained about that or any other thing, no one could remember hearing it.

At about the third glass of single malt, the story came out. My old friend, like the rest of us, had to spend a year as a surgical intern during the two-year rotating internship; he hated surgery and didn't mind telling the world. At the moment in question, he was the assistant at some neck surgery, with Lin performing the actual surgery. He was told to take a long pair of scissors and cut off the excess strands of sutures after Lin tied the knots; that was known as trimming the ligatures. They were working deep in the crevices of the patient's neck. Lin held up the loose ends of the knot and ordered, "Cut". My friend inserted the long scissors into the hole and snipped -- accidentally cutting right through the jugular vein.

As would be expected, a fountain of blood came up out of the hole, and Lin stopped it by putting his thumb on the cut ends of the vein. "Well," said Lin, "I guess we'll have to fix that." And did.

With tears in his eyes, my octogenarian friend cried out to the startled clubroom. "God bless you. God bless you, Lin."

Perhaps the point isn't clear to those who didn't go through the process, so let's be more explicit. Both my friend and I worshipped Lin, as a person, a teacher, and a surgeon. He was the perfect agent for his patients, without the tiniest trace of conflict of interest, income-maximizing or whatnot. He was as technically skillful as it is useful to be, but he was the thinking man's surgeon as well as the utterly faithful servant of the best interests of the humblest patient. He was, in the opinion of his closest professional associates, the best surgeon in the world. In need of surgery ourselves, all of us would have flown the Atlantic to have him operate on us. For reasons of his own, he was to spend the forty years of his professional life in a small country town with a small hospital, scarcely a famous surgeon but a beloved one to his community. Over the past sixty years, I have had a number of opportunities to know many surgeons who would be in contention for the title of the best surgeon in the world. Some have written books, some have struggled successfully upward through vicious competition, some of them would be called "Rainmakers" if the research world followed the pattern of lawyers and architects. One or two have won Nobel Prizes for surgical innovations, but that's different from being the best surgeon around. The best surgeon in the world was Lin, faithfully plying his trade in a little town that could not possibly know how lucky they were.

Frederick Mason Jones,Jr. 1919-2009

|

| Mason Jones |

Classical music, however else it may be defined, strongly implies music played by an orchestra, or at least a group of musicians. It thus should be no surprise that the members of a famous orchestra bond together for most of their lifetimes in a sense far beyond the ordinary meaning of teamwork. If you are good, really, really good, you will come to the orchestra as a boy, devote every hour of every day to the orchestra, and step down only as a famous old man when you sense that reaction times have slowed. You sit together, travel together, rehearse together, and talk a language of detail which no one else can fully comprehend. Mistakes that one of you made forty years ago in performance, are still joked about because your colleagues know you still feel the pain of it, just as they share their own infrequent but no less fully remembered, moments of failure, largely unnoticed by the audience. When one of your colleagues dies, you turn out by the hundreds for the funeral. And when the hymns are sung, the organist is ignored, struggling to keep up with the people who really know music.

Mason Jones attended the Curtis Institute, itself a collection of prodigies, and was hired by Ormandy after a single audition; a year later he took the position of a first horn and kept it until he finally sensed he was passing his prime and laid it down. He was featured in the many recordings which defined the orchestra, and the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet. He sometimes recorded as a soloist, but he thought of himself as an orchestral horn player, teaching orchestral horn at the Curtis to many generations of aspirants. He even conducted a little, usually in small groups. His comment on that was that it doesn't take much to be a conductor. "Just ask any orchestra player." At his funeral, it was related that the second horn once had two solo passages repeated within a larger piece, but when its time came there was silence. The second time around, it was played faultlessly. Afterward, Mason was asked what happened. "Fell asleep," he answered. And the second time? "I just played it for him."

|

| St. Peter's in the Great Valley |

Mason's funeral was held at St. Peter's in the Great Valley, illustrating that strange combination of artistic prodigies with modest beginnings, and the highest of high society, who mix together to create a great orchestra. A very well-groomed lady was heard to remark that this was where she had her coming-out party. St. Peters was founded as an Anglican mission church in 1700 in the Welsh Barony, built a log cabin church in 1728, replaced it with a little white jewel of a church in 1856, and added new buildings in the past few years to accommodate the population growth in the valley. The church has abundant well-tended land, sited on a hilltop surrounded by high hills, quite suitable for a college or private school campus. The homes in the area are a step beyond splendid, hidden in the wooded countryside. Unless you know precisely where to go, the tangle of country roads will defeat you. But the arterial of U.S. 202 is only a few miles away, and Philadelphia's silicon valley nestles beside the highway, inevitably closing in on the countryside. There will be horses and kennels and fox hunts in the region for another decade perhaps, but the new world is moving in on the old one, from all directions.

George Willoughby, 95, Peace Activist

|

| George Willoughby |

Age was nothing but a number for 95-year-old peace activist George Willoughby of Deptford. His worldwide antiwar protests and nonviolent teachings started when he was in his mid-40s and continued until just weeks ago.

Mr. Willoughby was planning a six-week trip this month to India to meet friends he had made during visits to the birthplace of his idol, Mohandas K. Gandhi, and probably to give some of his trademark peace talks.

But Mr. Willoughby died at home of heart failure Jan. 5, a month short of the journey.

A Quaker who led local protests and famous treks from San Francisco to Moscow and from New Delhi to Beijing, Mr. Willoughby recruited many advocates for nonviolent conflict resolution, said a friend and member of the Central Philadelphia Meeting, Nicole Hackel.

"Once you experienced him, you didn't forget him," Hackel said, adding that she became a Quaker in the 1970s because of Mr. Willoughby's influence. "George would engage in conversation with anyone, even a 5-year-old who was attending a meeting for the first time."

Mr. Willoughby became a household name for area Quakers after he became director of the Central Committee of Conscientious Objectors in Philadelphia in 1954. He soon was a frequent presence in the news, mostly under headlines with the words peace, marchers, and protest.

In 1958, Mr. Willoughby was one of five crewmen on the sailboat Golden Rule who received 60-day jail sentences in Honolulu for trying to sail to the area of the Pacific Ocean where the U.S. government was testing nuclear bombs in the atmosphere.

That was Mr. Willoughby's first of many incarcerations, said his son, Alan.

"The Society of Friends in Honolulu brought him a lot of decent food. . . . He always spoke highly" of the Hawaii jail experience, his son said with a slight laugh.

Two years later, Mr. Willoughby organized a dual-continent march to protest nuclear testing. Protesters in groups of about a dozen each covered six countries in 10 months between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Mr. Willoughby joined the group in Poland. Soviet officials stopped them 100 yards short of the Lenin-Stalin tomb in Moscow's main square, according to reports at the time. Instead of delivering speeches, the group was forced to stand in the square in a silent vigil.

In 1963, Mr. Willoughby embarked with about a dozen others on what he intended to be his longest hike - 4,000 miles from New Delhi to Beijing to promote peace between India and China.

Before his journey, a Philadelphia Evening Bulletin reporter asked whether there was a better way than marching to bring about peace.

Mr. Willoughby responded: "Most people of these countries walk; we can reach them. Even if it does no good at all, it is worth it. It's an idea I believe in, and if it produces fruit, so much the better."

After eight months of walking, Mr. Willoughby and company were stopped at the India-China border and barred from crossing into China.

In the next three decades, Mr. Willoughby's projects included the formation of A Quaker Action Group, which opposed the Vietnam War, in 1966; the Life Center Community in West Philadelphia, a training and campaign center for nonviolence, in 1971; and Peace Brigades International, a human-rights group, in 1981.

One of his most memorable contributions to South Jersey, family and friends said, was the creation of the Old Pine Farm Natural Lands Trust, 45 acres of natural conservancy in Deptford.

In his later years, Mr. Willoughby received honors around the world for his peace work, such as the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation award in 2002 in Mumbai, India, which recognizes those who promote Gandhi's ideas and values.

Born in Cheyenne, Wyo., Mr. Willoughby spent much of his childhood in the Panama Canal Zone, where his father worked in construction.

Mr. Willoughby was part of his high school's JROTC program, but, according to friend and biographer Gregory Barnes, he quickly realized the military was not for him.

A family rift led Mr. Willoughby to live in Des Moines, Iowa, with a family friend, Elinor Robson. In the 1930s, he received three degrees in political science, including a doctorate from the University of Iowa.

In 1940, Mr. Willoughby married Lillian Pemberton, a "birthright Quaker" he met in college. By 1944, he became a Quaker, fully immersed in the Religious Society of Friends' beliefs and ideologies.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Mr. Willoughby worked for the Des Moines office of the American Friends Service Committee before moving to Philadelphia with his wife and their four children.

After bypass surgery in 2000, Mr. Willoughby had to slow down. He wasn't able to participate in as many marches and rallies as he would have liked, his son said, but he remained active online.

One of Mr. Willoughby's last protests was in March 2003, an organized obstruction of the entrance of a federal building in Philadelphia to protest the war in Iraq. He took photos of his 89-year-old wife getting her head shaved as part of the demonstration.

"I've never seen her like that, but I like it," he told a reporter. Lillian Willoughby died last year.

One of Mr. Willoughby's last speeches was at Scattergood Friends School in Iowa a few months after his wife's death. He took a road trip with Hackel and one of his daughters to the Scattergood refuge camp's 70th-anniversary reunion, which was held at the school.

Once there, Mr. Willoughby did what he did best: talk. "He just fascinated the young people there," Hackel said.

Some of Mr. Willoughby's last words of advice were: "It is the duty of the opposition to oppose," his son said. "He thought it is your duty to speak up . . . for what you believe is right."

In addition to his son, Mr. Willoughby is survived by daughters Sally, Anita, and Sharon and three grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. Saturday at the Friends Center at 15th and Cherry Street

New Roles For Grandparents

Like everyone else, I had two grandfathers and two grandmothers. However, I can only remember seeing one grandmother on a single occasion when I was three or four years old, and the other three died before I gathered any recollection of them. Essentially, I never knew my grandparents. If they ever knew me, it was as a puking infant, don't he look sweet.

|

| Great Grandpa and Great Grandson |

One of the many unexpected consequences of the introduction of penicillin, polio vaccine and the like, is that my generation has had to invent the role of grandparent, without any models to follow. My grandchildren are all in college or beyond, with reasonable expectations of getting married and starting careers while I watch. I already have two great-grandchildren, and with luck will have lots more. To my knowledge until ten years ago, I never met anyone who had great-grandchildren, so I'm not entirely certain what I'm expected to do with them. I could ask others, but they don't know much, either. Society has evolved a database of experience about how parents are supposed to relate to children, and children have evolved literature about how they are expected to cope with their reflex hostility to their parents. Sigmund Freud made up huge mythology about such conflicts and emotions, and while we are shaking off a good deal of it, Freud did help define the general rules of behavior between parents and children. All of us believe we are exceptions to such rules, of course, but they do make up a road map of the land mines to avoid. Furthermore, most of us formed some firm opinions during the Vietnam conflict or the Summer of Love; presumably, most of our children feel a little silly about it now. Their folk songs record the mythology of that experience; even with guitar accompaniment, these songs all sound a little wry. Sorry about that. Wouldn't have missed it for the world, but sorry about that. Are ya gonna need me, are ya gonna feed me, when I'm sixty-four. Sixty-four? That was twenty years ago.

By this time, the sassy generation has had a chance to learn how sharper than a serpent's tooth it is, as a reminder that there have always been a few who lived King Lear's experiences, but now it could happen to anyone. The two generations, my children's and my own, have now lived a common experience from start to end, not just half of it as Freud depicted. But there's a new twist; the two generations think they have a role with the third generation. Both generations are unclear about what the grandparents' role should be with the new generation of young adults. I know what I think, you know what you think. Neither of us knows anything.

A thousand years of experience teaches how unwise it is to allow any relationship to revolve around gifts and the expectation of gifts. A mere two hundred years of experience make it plain to almost everyone how easy it is to ruin children by making life too easy for them. What does one do, then, with savings large or small, when grandchildren seem to combine aloofness with expectations? Does our society really expect us to favor our personal genome into eons of astronomical time? As one wanders occasionally through graveyards, it is very clear that our nostalgia for great grandparents born in 1814, is small indeed. Should we make an effort to create a lasting impression on such visitors from another planet, or should the whole misty idea of consanguinity be abandoned as a delusion? Should we take the wry advice of those who test our reactions with cynical descriptions? Should we, in a word, attempt to live out our lives with the perfect timing of spending our last dollar during our last hour? Come back in fifty years and there will be shelves of novels, plays, and poetry which tell the sad tales of those who made one choice or the other. Future generations of grandparents will still have to make their own decisions, but at least they will know how the world will view them. One generation will likely cling to the viewpoint of its contemporaries, another generation will reject such viewpoints as nonsense. Our generation will never be quite sure.

Among the funny things about this situation is the curious inversion of the social classes. Everyone notices how domestic servants hang around observing the behavior Upstairs; no matter how firmly it is rejected Below Stairs, employer behavior is marveled at and imitated to some degree. But in the past, those servant social groups who had their children at sixteen, their grandchildren at thirty-two, their great-grandchildren at forty-eight, knew something that those of us who defer our gratifications might wish we knew. The experience is raw and basic, and all the more important for that reason. Some budding novelist, hoping to cloak predictions as folklore, might give that theme a try.

The Lawsuit That Ate Philadelphia

|

| F. Hastings Griffin |

Hastings Griffin ("Haste") died last week in his nineties. The Orpheus Club put on a concert at his memorial service, and probably the Squash world put on something because he was the reigning world champion for his age group. And his wife was there in all her glory, having married and outlived three men, all of whom were roommates at Princeton; among women, that's a champion on a different level. I knew Haste as a fellow member of the Shakspere Society, where his booming voice was an arresting feature, particularly when you knew his motorcycle was parked outside, ready for the 30-mile trip home at night to his home near Valley Forge. But I knew him to be most famous as the lawyer who was on the losing side of a lawsuit which cost Philadelphia the whole computer industry.

|

| John Mauchly (on Left) and J. Presper Eckert |

As a matter of fact, I am very friendly with Ben Heintzen, the lawyer on the winning side of the same case. So, over a period of years, I was able to piece together the main facts of the case, checking remarks from one side against the recollections of the other. First of all, the computer as we know it was assembled by Mauchly and Eckert, on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania. Eckert had patented it, but the University had a rule that patents of the faculty belonged to the university. Unfortunately for that position, all of the money was government money. Right there, you have the makings of a big lawsuit, but there was much more. Ben Heitzen had discovered a paper by a Midwestern professor, Iowa I believe, who seems to have put the patent in the public domain by publishing the main substance of it, or what lawyers contended was the essence of the case. Furthermore, the case had many plaintiffs and defendants, working more or less together, but under the team leadership of Sperry Rand for the defendants, and Honeywell for the plaintiffs. The case dragged on for more than eight years, to the delight of the law firms and dismay of the Judge, who had been heard to growl that he didn't,t want to spend the rest of his life listening to this same case. All a losing lawyer had to do was wait for the verdict to tell you who won, and then file an appeal that the Judge had acted in prejudice. Furthermore, the Judge expressed the opinion that IBM wanted to mass produce computers, whereas Sperry was really only in the "patent infringement business." Somebody said that perhaps it was the Judge. Well, there's more.

|

| Sperry Rand Building |

It happens that Sperry Rand had round holes in their punch-cards, and IBM had square holes. The hanging chad issue became famous in the Gore-Bush presidential election, and you would suppose square holes would have more of a tendency to hang their chads than round ones, but it was actually the other way around. It seemed so to Sperry Rand, too, so they finally hired IBM engineers to tell them what the matter was, and those IBM engineers were hanging around while the trial was going on. They must have picked up the gossip in the lunch room, and reported back to Tom Watson at IBM something like, "Do you know what these people are doing with computers?" So they were given orders to stretch out the hanging chad matter and see what else they could learn. When Watson heard more, he told his lawyers to ask what Sperry wanted in return for letting IBM out of the lawsuit, and the answer came back, "Ten million dollars". To which Watson replied, "Pay them immediately because we are going to mass-produce those things." At that time, there were only a handful of computers, all doing such things as calculating field artillery aiming instructions. So Watson was essentially betting his whole company on success. At that time, General Electric, RCA, Sperry, Burroughs, Honeywell, and others were in Philadelphia, trying to imitate what they had heard the machines were capable of, so it was not a sure-fire gamble at all, but it was certainly successful in moving computers to upstate New York, and eventually to Silicon Valley.

|

| UNIVAC (Sperry Rand) Unimatic terminal |

Since half of this story comes from Griffin, let me reconcile a point that came up at his funeral. One of his partners heard him boast he had never lost a case, and when challenged on it, replied that it didn't matter what the jury decided, it was the judge who must approve the size of the settlement. His claim was based on getting settlements down to much less than the client was afraid it might be and was therefore persuaded he had been lucky. Well, in this case, it was a little different. The chief lawyer of the firm took the case away from Griffin and carried it himself. Shortly later, Griffin was heard to shout at the boss, "You are going to lose this case!". The next morning he was standing at the airport, next to the President of Sperry Rand. The President came close and asked him, "How do you think this case is going?"

To which Haste replied, "Well, sir, you'll have to ask my boss."

Abraham Rosenthal Letting Go

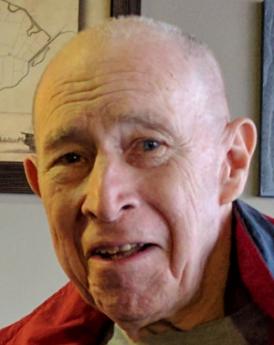

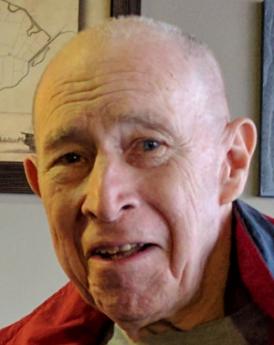

William H. Taylor Age 88

|

| William H. Taylor |

William H. Taylor Age 88 of Haddonfield

Died Monday, May 29, 2017 from complications of Alzheimers Disease.

He was born to Lavenia Skeggs Taylor and S. Herbert Taylor and is survived by his wife of 66 years, Helga Nepple Taylor. He is also survived by his sons, Jeffrey P. (Pat) of Burlington, NJ and James D. of Haddonfield, NJ, his daughter, Anne Taylor Connor (Ben) of Collingswood, NJ, his grandsons, Michael (Chrissy) Taylor of West Berlin, NJ, Adam Taylor of Medford, NJ, Will (Christine) Taylor of Summerville, SC, Joseph Connor of Collingswood, NJ, 2 granddaughters, Aurora Connor of Seattle, WA and Fiona Connor of Arcata, CA and 2 great-grandsons, Lucas and Jeffrey Taylor of Summerville, SC. He also is survived by a brother, David L. Taylor of Medford, NJ.

He was a native of Pennsauken and attended Pennsauken and Merchantville schools where he was captain of the championship swim team and played bass in the Blue Serenaders, a local swing band. With his brother, David, he also worked as a lifeguard in Wildwood Crest. He obtained his bachelor of science degree in Civil Engineering from Princeton University in 1950, after which he enlisted in the Navy as an Engineering Officer on a destroyer escort during the Korean conflict. In 1952, after completing his tour in the service, he joined his brother David and father Herbert at the engineering firm of Sherman, Taylor, and Sleeper. He also started night school and received his masters in Civil Engineering /Urban Planning in 1956 from the University of Pennsylvania. He obtained his Professional Engineering, Land Surveying and Planning Licenses. He and his brother became executives and principals of the engineering firm which evolved into Taylor Wiseman Taylor. At the time of Bill's retirement in 1981, he was president of the firm.

He was a member and fellow of the American Society of Civil Engineers, New Jersey Society of Professional Engineers, American Consulting Engineering Council, New Jersey Society of Professional Land Surveyors, New Jersey Society of Municipal Engineers, the Water Pollution Control Federation, the American Water Works Association, the Water Resources Association, U.S. Naval Institute and the Advisory Board of Widener University.

He served as Burlington City, NJ engineer for 22 years and oversaw all the urban planning and engineering design services that resulted in major redevelopment and historic restoration of the City. He was a leader in the development of Southern New Jersey, including the Route 295 and Route 55 corridors and numerous housing and commercial communities.

Bill was early to understand the importance of the environment and helped preserve thousands of acres of open space.

He was an American Society of Civil Engineers District Director and Chairman from 1978-1984 and National Vice-President of the American Society of Civil Engineers. He was a Proprietor of West New Jersey and served as the 12th Surveyor General of West New Jersey for 48 years, a record term of service of which he was very proud.

He was Chairman of the Haddonfield Planning Board and worked with others to create the Historic District Ordinance for Haddonfield. He was also Director and President of the Southern New Jersey Development Council, Director of the NJ Alliance for Action, Director and President of the Guidance Center of Camden County, Board Member and Facilities Chairman of Cooper Hospital, Director of Fidelity Mutual Savings and Loan Association and Director and President of Indigo Association, Ltd.

Bill had many hobbies that included scuba diving, sailing, swimming, hiking with Helga throughout the United States and Europe, biking and cross-country skiing. He also rehabbed several homes at the Jersey shore, designed and built a home in the British Virgin Islands, a floating porch boat on the Nacote Creek in Port Republic, a barn and various additions to friends homes. He loved model trains and designed a very elaborate train layout for his home. He was passionate about current events, loved a good political debate and was an early supporter of Senator Bill Bradley.

Funeral services will be private. Contributions in his memory can be made to Planned Parenthood of Northern, Central and Southern New Jersey, 196 Speedwell Road, Morristown, NJ 07960 or the Alzheimers Association at www.alz.org.

With Bills wide interests, he was a true renaissance man. Generous, hospitable and larger than life, he cherished his broad and varied circle of friends.

No Well-Run Hospital will Tolerate Bullet Holes

When they repaired our bullet hole at the Delaware Hospital recently, it was much more than a renovation of the clinic pharmacy. It symbolized a new generation assuming power in the hospital.

There were originally three bullet holes in the clinic: mine, Mrs. DuPont's, and the pharmacy. Mrs. DuPont and mine were quietly patched soon after the incident, but the small hole in the ceiling above the pharmacy window went unrepaired for ten years. That was not an oversight.

Hospital people who were active spectators of the shootout repeatedly protested any attempt to repair the small unobtrusive hole in the false ceiling, bothering no one but symbolic to a cluster of insiders. Even when the wing was completely gutted and renovated, that small patch of the ceiling was left untouched. Because some of us wanted it left alone, our wishes were respected in "our" hospital. The Delaware Hospital, you see, once experienced a shooting incident. It happened very much like a certain episode in the movie called “The Godfatherâ€, and indeed the recent criminals may well have got the idea from the movie. In any event, a very dangerous criminal was actually brought from prison to the hospital to have an x-ray. Ordinarily, prison authorities give inmates no advance notice they are going to the hospital. However, this prisoner was to have his gallbladder x-rayed. We don’t x-ray gallbladders this way very much at the present time (ultrasound examination has largely replaced x-ray) but in those days it was necessary to swallow several pills the night before, so the dye could have time by morning to concentrate in the gallbladder. Therefore, when the prisoner was given the pills to swallow, he knew he was going to the hospital in the morning. His buddies on the outside knew he was going too, and where he was going. How this grapevine works is, of course, a mystery, but it is natural to surmise some prison guard accepted a bribe.

So on a nice uneventful diabetic clinic morning at the hospital, the prison guards arrived with their manacled prisoner, marching him down the clinic corridor toward the x-ray department at the end of the hall. As this jaunty group passed the men’s room, the prisoner pleaded to be allowed to relieve himself. The guard went into the men’s room with him, unlocked his handcuffs, and waited. After washing his hands, the prisoner pushed a crumpled paper towel deep into the trash can, seized the gun which his buddies had previously hidden there, and wheeled around, shooting.

His getaway was well planned and smoothly executed. Everyone in the area dived for cover as he fired shots in random directions. By the time people began to peep, he had run down the hall, out the door, and into a waiting car. He was gone.

One of the volunteers in the clinic was a certain Mrs. DuPont, also a member of the board of trustees of the hospital. She was about thirty-five years old, surely one of the ten most beautiful women in the nation. How close the bullet really came to her I don’t know, but it was certainly closer than any bullet had ever come before, and she was scarce to be blamed for feeling she had a close call. My bullet was lodged in the wall a foot or so from the desk where I usually sat on Fridays, only this wasn’t Friday so I wasn’t there to have a close call. But if it had been Friday I might well have been sitting there, and I might well have had a close call. I mean, this event was really exciting.

So we all had a lot to talk about, with a lot of close calls we almost had. A group of old friends and old casual acquaintances were united in a shared experience which provided a welcome common topic of conversation. The doctors and the orderlies, the chambermaids and the heiress, the nurses and the administrative clerks, had a common event. Even if any of them manage to live another fifty years, I suspect they will rejoice in meeting anyone who can reopen the reminiscence.

The group had a strong sense of fraternity even before this notorious event, but it was formal. Titles were used, rules were pressed, formalities respected. The nurses wore the caps of their diploma schools, the volunteers wore pink aprons, the interns wore white suits. The attending physicians wore street clothes but they were a sort of uniform, too. In Wilmington, I wore a non-matching tweed jacket and grey flannel pants, like the other doctors. In Philadelphia, In some circumstances, it would have been a dark suit. The clinic ran by rules finely understood even if entirely unwritten. It was quite acceptable to ask Mrs. DuPont to dispose of a bottle of urine, but it would have been unthinkable to ask her to have lunch. We all nodded and smiled at each other in passing, but we didn’t chat except within our own groups. But the shooting episode was an enduring ice breaker. It was something you had in common with the clinic group, to which everyone else was an outsider. People retire, people, die, Times Change. New brooms sweep into administration and unknowingly sweep aside old icons. A new pharmacist regarded the bullet hole as a small curiosity which someone had told him about. A new head nurse had other things to worry about.

On the fourth or fifth time the contractors set about to patch the ceiling over the pharmacy window, no one of the original group was present to intervene. Since the area had been so totally renovated as to be almost unrecognizable as the old clinic with curtains between the beds, the little bullet hole was the last link with the past for the dwindling but still fairly numerous group of people who remembered another era. It is perhaps most forgivable for the heedless young professionals who bustle through the place, not to have known nor even to recognize the name of Dr. Lewis B. Flinn. Dr. Flinn died a few years ago, in his eighties, looking like a Roman Senator almost to the end.

Lew Flinn dominated the medical scene in the entire state of Delaware, but particularly in Wilmington, for sixty years. There were those who called him a dictator, but he was so universally revered it was difficult to find a single person who would criticize his decisions and actions. Some people, particularly the outs, the people who don’t count, resented his power and prestige. But in the thirty years, I knew him, I never heard of serious opposition to even one of his proposals. Lew Flinn can fairly be said to have transformed Delaware medicine from a second- rate hodgepodge into a professional environment of the first rank. Within the smallest state in the Union, he created the second largest private hospital in America. Late in his career, he investigated the idea of founding a medical school in Delaware and concluded without serious opposition that the quality of physicians in Delaware would be harmed by it. A new medical school takes time to amount to something and provides second-raters until it gets established. By contrast, Delaware was currently able to attract the cream of Ivy League schools to practice there, and it would be a step back to do anything but continue the process. There was nothing prideful in this conclusion, but there could have been. When Lew Flinn first came to Wilmington as a doctor he was diving into a pool of third rates, and misfits. Why in the world would an honor graduate of John Hopkins want to practice in Wilmington?

Lew Flinn was in fact such an honor graduate of John Hopkins that he eventually acquired certificate number one, of the American Board of Internal Medicine. With his training and natural ability, Flinn could have mattered anywhere he wanted to. He could have been successful in just about any medical career. Instead, he chose to come back to his home town. And make something of it.

Flinn had everything, absolutely everything. Wealth in the family, excellent connections, brains, and training. His manners were so instinctively gentlemanly that the simplest conversation would intimidate any awkward soul who was unable to match the occasion with the appropriate response. He could be brisk and disdainful, and commanding when the situation called for strength, but he seldom needed to call on anything but gentle persuasion.

However, of all the qualities which served him in his career of transforming Delaware medicine, surely the most important one was physical beauty. Eyebrows tend to rise at that kind of a statement. Nevertheless, a true understanding of the magnetic power of the man is best acquired by going to the Delaware Academy of Medicine building overlooking the pictures of former presidents. The first picture on the wall is of Lew Flinn, at perhaps age thirty. No movie star ever had a publicity picture taken which radiated a more electrifyingly handsome profile. When Lew Flinn approached a DuPont heiress with a request for money for the hospital, he got it. And his courtly manner turned the response of men from envy to admiration. If you want to get things done, look and act like that. While it was absolutely impossible to think of Flinn as a philanderer, it is easy to see why he was an irresistible medical evangelist.

Wilmington had four hospitals during the early decades of Flinn's career, and three of them were supported by different owners of the DuPont company. Flinn concentrated on the Delaware Hospital, but he also was active in promoting the Memorial and the Wilmington General Hospital. Eventually, he became chairman of the Department of Medicine of all Three. That may have seemed like a bit much to some of his colleagues, and at one point he was voted out, by the Medical staff of one of them. His power and prestige at the Delaware Hospital were never challenged, and he steadily built up its medical staff by recruiting specialists from out of town to came to Wilmington; I was one he recruited. He appeared out of the audience at a Chicago meeting where I gave a paper and invited me to have dinner with him. I can think of no other reason why he would have been at the meeting, and I heard similar stories from others who were recruited. I don’t believe he was ever paid a penny for his administrative work.

Flinn became a member of the board of trustees of the hospital, and from that position was able to advance the hospital in a number of ways. He knew what the town needed in the way of laboratories, equipment, and specialists. The trustees were guided into doing all the expensive things which make a hospital into one of the best in the country. He saw to it that the doctors were pampered. They had their own lounge and coat room, constantly supplied with hot coffee and daily newspapers. There was a separate doctors' dining room (the senior hospital administrators ate there too and were welcome members of the medical community), there were white table cloths. On Friday, fish day in that era, there was an oyster stew or lobster bisque. It was a great clubhouse to have around and it was so by design. It was lots of fun to come from Philadelphia, attend a doctor’s conference, work in the free clinic, and adjourn for lunch. Flinn built up a medical staff by courtesies when no other inducement would have done the job. We all liked each other.

It made Lew Flinn uneasy, to have to describe to other people what he was up to, what his plans were. If he proposed something, it was a proposal for immediate action and he meant to have it happen right now. On one occasion, though, he confided in me his philosophy of teaching programs for the internet and residents. He was not particularly interested in attracting resident physicians to the hospital, although they were welcome enough. The purpose of the teaching program for the interns was to serve as a framework for continuing education of the practicing physicians of the community. He fed them oysters to get them to come to the conferences and to have lunch with other practicing consultants in the dining room. You educated practicing doctors by asking them to help educate the interns.

After he retired, he embarked upon the project which was his greatest achievement, the unification of the three hospitals into the Delaware Medical Center. His reasoning was not so much that consolidation would reduce duplication of equipment, although that was an argument. The main need for a 1200 bed institution was to create pools of patients which were sufficiently large to make it possible for a specialist to make a living. When that was possible, Delaware could relax its constant recruitment efforts and expect the institution to generate a first class staff without subsidies or teaching salaries. It is my present information that this plan worked beautifully.

The new building, on ground donated by a DuPont widow, is a spectacular piece of hospital architecture. Money cannot buy a more sumptuous physical plant. One suspects Lew Flinn’s fundraising capabilities were a major factor in the lavishness, probably mostly through a spontaneous wish by his admirers to build a suitable memorial, to his memory.

Mary Stuart Blakely Fisher, MD

Working as a woman doctor in the days when women were limited to 10% of the admissions to many colleges, and often excluded entirely, Mary Blakely graduated first in her co-ed class at Binghamton (NY) High School, followed by first in her class at Bryn Mawr College, and the first in her class at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. In fact, she had the highest grades in five years at Bryn Mawr and was selected as a medical intern at the Massachusetts General Hospital, going on to the nation's most prestigious radiology residency under Ross Golden at Presbyterian Hospital in New York, and subsequently with Aubry Hampton. During much of that time, she lived in Philadelphia and commuted on the train to New York. She had married me a year earlier, and the train conductor grew visibly more anxious as she became increasingly pregnant during the several-month commute from Philadelphia's Broad Street Station to Penn Station in New York. Both railroad stations have since been torn down, and the baby she was carrying has been retired for ten years after being Managing Director at Morgan Stanley.

The State of Pennsylvania required a rotating internship, and while I still believe that is the best sort of internship, it was particularly galling to have the reason given that her internship was the reason for refusing to grant her a Pennsylvania license. So she got a job at the Philadelphia Veteran's Hospital, and later at Philadelphia General Hospital, the City's charity hospital of three thousand beds. Well, she never mentioned this Philadelphia affront to a premier academic Boston institution, but I didn't. Perhaps church politics are more vicious still, but this little episode illustrates how very nasty medical politics can get. Perhaps it is a feature of the human personality everywhere, but some situations freely tolerate it, while a few others just don't.

Well, in time she was offered the chairmanship of just about every Radiology department in Philadelphia, and turned them down, saying she didn't want to be chairman of any department. Perhaps she meant any department in Pennsylvania, but she never did make her feelings known. Eventually, she did become Professor of Radiology at Temple University, where she happily taught the residents for many years, during the course of which she was given the Madam Curie Award, the Lindback Award, and various other honors. She had an amazing facility to start dictating reports on x-rays before they were completely out of the envelope and always won the interdepartmental contest for diagnosis of strange films, to the point where other, mostly male, radiologists were afraid to compete with her. She won the Lindback Award for Excellence in Teaching. I used to say I didn't know whether she was any good or not, but I never met a radiologist who wasn't thoroughly intimidated by her ability to make a strange diagnosis at a glance. All her life she got along with five hours of sleep, invariably getting to bed after me and getting up the next morning before I did. Essentially, there were twenty-eight hours in her day.

So it wasn't just radiology where she excelled. Her father once told me there was nothing she could turn her hand to, where she didn't excel. Especially female skills. She was past the point of competing with males and beating them, but female skills were something else. She was a master cook, a demon housekeeper, a champion seamstress, a masterful dinner partner. Athletics were never attempted because she knew very well that men hate to be beaten at golf or tennis. It was the era of Kathryn Hepburn and Grace Kelly, and with a minimum of makeup, she turned heads where ever she went with that Bryn Mawr look about her and her painfully simple clothes. Several of my classmates, usually from Princeton, was struck dumb by her looks. For example, my book editor from Macmillan had a classmate of mine for his doctor. That Park Avenue physician never married and confined to the editor that he had been carrying a torch for her, all his life. It brought to mind the boastful lines from Congreve, in The Way of the World:

"If there be a delight in love, 'Tis when I see, The heart that others bleed for -- bleed for me."

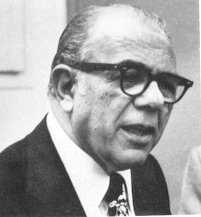

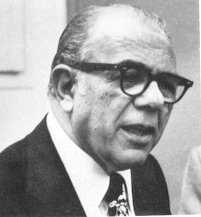

The Godfather

|

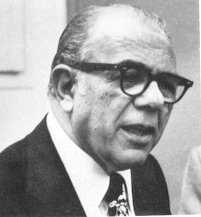

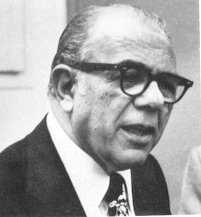

| Angelo Bruno |

There are people who deny that Philadelphia has any organized crime; and it certainly doesn't have a Mafia. That may be true, but still the rumors do persist. They say in the street that someone named Angelo was once the head of the mob, and that may not be true either. However, it is true that one day he had his head blown off sitting in his car, and it is definitely true that the sidewalks were swept and completely safe for several blocks around his South Philadelphia house. If there was an empty parking space along that block, no one took it.

One day before he met his untimely end, he was a patient on the seventh floor of the Pennsylvania Hospital, and the patient in the next room was a ninety-six-year-old starchy matron, whose faculties were a little impaired, and who had a daughter named Mary Stuart. As commonly happens with old ladies at sundown, one evening the matriarch became a little confused, and shouted out, "Mary Stuart!" After a brief pause, she repeated, "Mary Stuart, Mary Stuart!" This continued for an hour, and finally, Angelo put on his bathrobe and came around to see what was going on next door.

When he appeared at the door, the old lady sat bolt upright and said, "Young man, just who do you think you are?"

Angelo smiled broadly and replied, "Why, I'm Mary Stuart."

Specialized Surgeons

|

| Regina E. Herzlinger |

Local attitudes always somewhat persist among migrants from home. What's distinctive about the Philadelphia diaspora is how unconscious most of them are about still carrying the hometown mark. Philadelphia leaves a prominent birthmark, but it's sort of back between your shoulder blades and you forget it's there. What occasions this observation is a Christmas call from a prominent California surgeon who was once my roommate, back in the days when residents were actually resident in the hospital. More than fifty years ago Bill Doane also served as best man at my wedding. Our conversation turned to clots in the lung, and he related a story. He had once fixed a hernia for a 22-year old girl in the days when it was customary to keep hernia cases in bed for a while. Getting out of bed for the first time, she coughed and turned blue, suddenly on the edge of death. Taken back to the operating room, her chest was opened, and Bill removed a clot which was essentially a cast of the blood vessels of one entire lung. As surgeons like to say, she then did very well.

One doctor can tell such a story to another doctor in four sentences, while lay people who overhear it miss the whole point. The fact is, not one surgeon in ten thousand today could carry this off. Nowadays we train thoracic surgeons to open the lungs; they never repair hernias. Conversely, we train hernia surgeons to fix a dozen hernias daily through a little telescope; they never open a patient's chest. So it is hard to imagine many contemporary surgeons who could recognize this disastrous complication of hernia repair, then fix it themselves in time to rescue the patient. Although this disheartening decline into repetitive super specialties has been forty years in the making, it has been recently popularized with the general public by Regina E. Herzlinger, a Harvard business professor. Writing books and speaking to businessmen groups, she has popularized the proposal to outsource the general hospital into what she calls "focused factories." She rightly characterizes the medical profession as reluctant. She's a nice person, and undoubtedly sincerely believes focused factories will save money, improve quality. But we must not let this idea take hold.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

Specialty hospitals have actually been given more than a fair trial. About a hundred years ago, the landscape was peppered with casualty hospitals, receiving hospitals, stomach hospitals, skin and cancer hospitals, lying-in hospitals, contagious disease hospitals, and a dozen other medical specialty boutiques. With a few notable exceptions, they all failed for the same reason. Sooner or later they found they could not adequately service their specialty without the backup of a full hospital service. Children's hospitals do thrive, but they have patients who are generally of the wrong physical size to fit adult hospital facilities and equipment. There are plenty of things to regret about general hospitals' design, but the inescapable fact is they all must have a very wide range of services to perform any mission, no matter how discrete. It would be still better if the doctors had an equally wide range of skills in their own heads, but the avalanche of innovation and lawsuits has forced sub-specialization, compartmentalizing, and narrowness of viewpoint. Circumstances have forced the profession to hunker down, but that trend must be resisted, not celebrated.

The instant and successful repair of pulmonary embolism make a dramatic illustration, but the reasons for broad medical training are more extensive than that. In the first place, it is much cheaper to use the generalist office than to bounce people to a gastroenterologist for heartburn, a psychiatrist for anxiety, and a dermatologist for pimples. The American employer community is desperate for a way to reduce its burden of employee health costs, and flocks back to their nurturing business schools for advice. They would do better to seek repeal of the tax dodges which tempted them into their present muddle, of course. But in any event, they must be persuaded to recall the disaster of managed care and at least, avoid meddling in hospital design.

That's the cost issue, where specialization surely raises costs. Constant repetition of the same procedure seems superior to first-time fumbling, although it is questionable how long it takes a well-trained surgeon to pick up a new procedure and do it well. But for this system to work, the referring physicians need to be more skillful, not less, in choosing a good one to refer to. There's just nothing like the experience of working for a few weeks in the specialty as a rotating intern, to tell you what to look for and what to avoid. If every doctor in a hospital is making a dozen internal referrals a day, the cumulative effect on the quality of the whole institution is dramatic -- when they have had sufficient past involvement in the specialties to which they now only refer patients. Some specialists will become popular and rich; others will sulk around unnoticed for a while, then go elsewhere. This process, of course, occurs everywhere; what's institutionally distinct is the culture underlying the standards for preferences.

We'll talk later about the Doane brothers of Bucks County, who were judged to be too handsome to hang. Right now, the point of this story can be summarized by the old Pennsylvania Hospital adage, that you must first be a good doctor before you can be a good specialist. Not only was the Pennsylvania Hospital the first in the nation. For sixty years it was the only hospital in the nation, and for decades after that, it was the only hospital in Pennsylvania. In medical history circles, it is said that the history of American medicine, is the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital.

The Troubled Times: Gray Lady in Limbo.

Today’s New York Times, the stately and respected establishmentarian of American newspaper industry, will sell almost a million copies around the nation.

Its news and editorial pages will send ripples of concern or support to those who run universities, business and government. Its front page will help define what is news, setting an agenda that will help guide television networks, newspapers and national news magazines. Its reviews can launch young talent or snuff it out. And its four full sections will undoubtedly be the first public version of yesterday’s happenings reviewed by future historians the newspaper of record’s durable rendering of the events of January 7, 1986.

This powerful newspaper, whose readers include most of the nation’s elite or “the very very very top top top, “ as Times Co. Vice Chairman Sydney Gruson described the paper’s audience, conveys solidity and security to its loyal subscribers . But as many of those who produce The Times and some of those who obsessively read it said in interviews over the past few months, this image of unshakable stability is increasingly misleading.

The New York Times today is a nervous institution preparing for what may be one of the most difficult periods in its 134 year history the retirement of Executive Editor Abraham Michael Rosenthal. In May 1987, after almost 20 years of increasing dominance over this powerful journalistic kingdom, Rosenthal will reach 65, the mandatory age for Times executives to move on, and the tremors have already begun to shake the foundations under the gray lady of the Times Square.

Talented young journalists, who once yearned for even the lowest job on The New York Times, are increasingly opting for better position on “publications The Times once considered not even in the competition,†as one top editor lamented recently.

Potential heirs to Rosenthal’s journalistic throne find themselves nervously doing their jobs while anxiously eyeing their competition. “It is a paper in waiting,†as a reporter in the Washington bureau put it. “We’re in a kind of psychological limbo.â€

Once the waiting is over, the change at the top of The Times will be more than a mere switch in corporate personnel. It will be the end of a brilliant, Lucrative and tumultuous era two decades in which one of the world’s most distinctive and controversial men.

The daily offering of a great newspaper is rather like the menu of a great restaurant a direct reflection of the energy and personality of the person in charge. And it seems a virtually universal view among The Times’ 650 writers and editors that in the Rosenthal era, the chef’s personality has been dominant as never before. Famous for his strong emotions, Rosenthal has total control over the news side of his institution. Basking in a strong paternal love or cowering under his anger, Times journalists have been known to despair when they have taken what Rosenthal considered a wrong journalistic or personal step or to rejoice when one of his warm notes arrived the interoffice mail.

Rosenthal also gained power at The Times in a period when the newspaper struggled to pull itself out of a financial slide. Through the paper prospers today as never before, in the early 1970s there were whispers on Wall Street that it might have to close, so bad was it financial performance. Times Publisher Arthur Ochs (Punch) Sulfberger spent a good deal of his time denying to the financial community that he would ever perform euthanasia on the staid but solid journalistic product that had been in his family since 1896.

In New York’s financial crisis of the mid 70s, when the city government perched on the cliff of bankruptcy, Times advertisers scaled back their media buys. Circulation dropped as readers fled to the suburbs. At the same time, printing costs soared, union contracts brought rising wages, and the various journalistic and financial parts of the paper run like independent fiefdoms sometimes seemed to compete more with each other than with any news organization outside the paper.

But almost at the same time such publications as Business Week were lamenting that “the financial health of The Times has seriously deteriorated,†the paper was beginning to recuperate primarily through the efforts of three men: Sulzberger, Walter Mattson, now president of The New York Times Co., who pushed the paper to appeal to new readers in the ‘70s, and Rosenthal, who captured those new subscribers by providing stories about asparagus and anthropology as well as politics and the economy.

“I think what I’m proud of is that I was able to change The Times and not change it,†said Rosenthal of this crucial period.

“I remember the day I became managing editor, trying out my fancy new desk, sitting behind it, and Harrison Salisbury, then assistant managing editor, came in and said, ‘Well, Abe, you’re the first editor of The Times that will have to worry about money,’ Rosenthal said recently in an interview for this series.

Marketing data in the early ‘70s showed that the paper was missing thousands of readers Times managers though should be subscribers, Rosenthal said. “There was no particular demographic or educational reason, “he said. “If everybody had behaved like a good American and read The Times everyday like they should have, we wouldn’t have had this problem.â€

“I guess the fundamental decision had to be made by Punch when we were in this (economic) crunch,†Rosenthal said later. “That is, there are two ways The Times could go a lot of business face the same problem and that is to put more water in the soup or more tomatoes in the soup. And the business decision here…was to put a lot more tomatoes in the soup. You know, make it a bigger, fatter paper.â€

Rosenthal was referring to what some Times observers call “the sectional revolution†the expansion of the paper into four weekly sections. The traditional news sections were bolstered my new ones devoted to business, sports, home decorating and life styles, entertainment and science. The first was Weekend, which appeared on Friday, April 30, 1976 by Sports Monday and, in May of that year, Business Day (daily).

Although the style and panache of the new sections were widely admired, The New York Times as it was called was not universally applauded. In 1977, when Rosenthal was about to be promoted to executive editor, it was a standing joke in the Times news room that the paper was about to create another innovative section. It was going to be called News.

“It wouldn’t have meant anything it the Times had become a different kind of paper, if its character had changed,†Rosenthal said, responding to those early critics. “It didn’t it’s still the same paper. You pick it up, you like it or you don’t like it, it’s The New York Times.†While Rosenthal gave in to additional sections for “soft†features on Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays they were largely the results of prodding from Mattson on the business side he says he drew the line at Tuesdays. The Business executives at The Times, looking for segments of the economy that could spend big money on advertising wanted a fashion section, he said.

“I didn’t want to do it. I had this stomach feeling against it,†he said, adding that fashion would have been “a kind of parody, really.â€

“I wants to do something very Timesian. I wanted to do something for the readers who loved us and stuck with us,†he said, “I had an image in mind, it was (author) Teddy White’s face, a very nice guy, our type of reader in a sense.â€

So, as Rosenthal recalls it, he borrowed space from other sections of the paper and simply started putting out the science section. “I remember somebody from the business section coming down one day and saying, “Abe, you stole Tuesday,†he remembered.

Says one editor who has been critical of Rosenthal on other matters: “The Bottom line virtue to Abe’s regime is that you have to give credit to anybody who has conquered that transition from an uncomplicated newspaper to very complicated one without a diminution of quality.

“It’s really hard to remember how boring and lazy this newspaper was. We were always quick to punditize, and when we did reporting, we sometimes did it very, very, well,†said the editor. “But we weren’t very hungry. We rested on our laurels a lot.â€

Charges of Elitism

As the paper of the “very very very top top top.†The New York Times “product,†as it now called in business circles, carefully caters to its consumers, and some critics suggest that the newer, more lucrative Times misses many of the social issues that were widely covered in that earlier era.

A Story on Nov. 2, for example, analyzed the anxiety of parents scrambling to make certain their child goes to the “right†nursery school in order to get into Harvard. When Hurricane Gloria swept across the East Coast, The Times carried as large front page story about a young couple who could not get electricity for their mansion, a Yankee version of Tara complete with a storm damage column on the front portico.