Related Topics

No topics are associated with this blog

Problems of Newborn Babes

Future Medicare costs are more predictable verbally than with data. Half a dozen diseases make up most of the cost of Medicare, and it can be predicted that research will eliminate some of them. Although at first the new cost of treatment will raise costs, eliminating the disease will eventually lower them. The last year of life will almost certainly remain expensive because everyone will eventually die. In that sense, it is easier to predict continuing high costs for the last year of life, than for Medicare as a whole, except for scientific progress driving disease out of lower age groups into Medicare. In fact, the enduring costs of the last year of life are about the only thing predictable about Medicare. So the old folks needn't worry; no one will seriously propose eliminating the program until the future becomes clearer.

However, diseases will surely be eliminated, longevity will increase, and the last year will be expensive. It seems rational to give Medicare recipients the same incentive to be frugal about spending which younger ones get from Health Savings Accounts: if your medical costs go down, we will transfer the savings into retirement funds which many of you badly need. In the case of Medicare beneficiaries, that probably means transferring them into current Social Security payments. Another purpose is also served, which is to make the offer while there are no surplus funds. It would serve the purpose of assuring the elderly that funds going into their medical care will be diverted to the consequences of good care, which is improved longevity. The consequences of not staking out this position in advance might be, just might be, the diversion of funds into battleships, sugar subsidies, and other worthy causes. And having been shown clean hands with this proposal, perhaps the seniors would calm down and consider other proposals about Medicare.

For example, how the books are kept. Medicare is funded by three sources, the wage tax on working people (3%) of their income, the premiums the old folks pay, and the subsidy from the general fund. However, the money is not put into a big Medicare pot but rather designated to particular parts of the program. The fiction is maintained that hospitals are almost entirely funded by the wage withholding tax, more or less guaranteeing that the hospitals will be paid, no matter what, because the wage tax has already been collected as cash in hand. The rest of it is less certain subsidies and premiums, much of it borrowed from foreign nations. You can see the hospital lobbyist in this: hospitals get paid first, no matter what. And so far, it hasn't mattered much, because everyone got paid in full. But however meaningless, it represents a give-back which the hospitals would probably be reluctant to give up.

Since it represents a reason to resist reductions in Medicare funding by the federal government, it potentially stands in the road of gradually reducing Medicare funding for other purposes. Including shifts from medical care to retirement funding, let's say. And it serves no other purpose I know of.

shows the "costs" we already spend per person for healthcare, adapted from Dale Yamamoto, the actuary who has written most on the subject. You will pardon a brief excursion into jargon. Costs are compared with revenue variations. Costs are ordinarily more reliable than revenue projections, both of which must reach the same final amount. But in this case they are based on reimbursement reports, both overpayments, and underpayments, themselves responding to cost shifting and artifacts of cost-to-charge distortions. Reimbursements are modified by competitive loss-leaders, mis-projections, and changes over time. They are then further distorted by changes in the Law by politicians. An example of that was the imposed rule, cross-age ratios may not exceed a certain ratio to each other. Costs change over time, and they respond with alacrity to reimbursement decisions. They are then further distorted by changes in the Law by politicians, as in the imposed rule on cross-age ratios of the Affordable Care Act, which is really a roundabout method of introducing cross-subsidies between age groups. We have to take the actuary's word that approximating the deductibles and co-pay costs makes little difference in the final result, but one caution is firm. Since these figures represent the cost which providers send to the insurance company, they necessarily omit the cost of health insurance itself. It would be informative to know whether insurance costs add 1% or 20% to the average cost, and then decide for ourselves whether it makes a significant difference. Since it is obvious these curves are all approximations, their apparent precision can be treated with less caution than the selection of inputs. The shape of the curves is accurate enough, but since we are mainly interested in comparisons between insurance approaches, it is disappointing to find so little data to use.

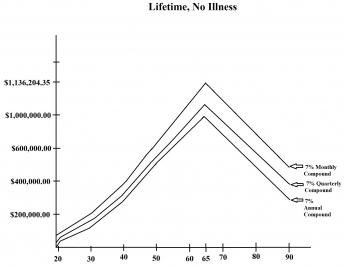

Turning now to the above graph as an introduction to the topic, its revenue projection comes from investing $400, at birth and in escrow. Seven percent is easy to calculate in your head since it doubles every decade. Eight percent is what we estimate to be the highest (safe, net, average long-term) return an investor could expect to maintain for decades, also happening to dramatize the major improvement in final income which is possible from very small, but consistent, efficiencies. Stated another way, it illustrates what it costs not to resist HSA intermediaries who suggest interest-free deposits for long periods of time but to propose instead to put the money in escrow at long-term rates. By current law, deposits stop at age 65, and the decline in balance to age 85 represents retirement income. Somebody is going to gather this income, and it might as well be the HSA depositor. If you put it in escrow so you can't spend it, you become entitled to long-term rates, but if you insist on a demand account, you get demand rates, which right now are quite low. To solve this dilemma, we propose using an escrow to pay for your last year of life, which is a pretty certain long-term bet. That leaves the rest of the account available for routine health costs, and the government should be persuaded that removing up to 30% of their costs is a good deal for them, too.

(While only 50% of total health costs are paid by Medicare, 30% of what Medicare does pay is for the last year of life. It grows to 50% of costs for people over 85 in the last year of life, and improved longevity pushes more people into that group. The sole financial advantage to growing old, is compound income increases considerably at the far end, too. At this distance, it is not possible to see how these two factors balance.)Actually, we are about to propose that part of the Medicare withholding tax, collected between ages 25-65, be isolated (escrowed) as the source of long-term money deposited in HRSA accounts because the money is collected for Medicare -- whose own total costs would be reduced by expunging the last year of life costs. Because all such innovations have uncertainties, the $400-at-birth illustration is offered to show the way shortfalls could be supplemented at low cost, but if unneeded, used as more retirement income. Another direction to take might be to expunge costs for the last two years of life. Or three, or four. Half of Medicare costs right now occur in the last four years of life. This is merely the flexibility feature which makes long-term uncertainties bearable. The real proposal is simple: just use a portion of the Medicare withholding tax to buy yourself the means to acquire the last-year-of-life costs. At the moment, that tax is 3% of income. Also at the moment, terminal care is about 25% of last-year costs, but it probably will eventually be over 50%, as the population ages and crowds death expectancy, not merely into Medicare, but into people older than 85.

That briefly sketches the plan for Medicare -- phase it out gradually and voluntarily (as research eliminates the ten most expensive diseases), offering a choice of more retirement funds whenever the individual prefers them. It's intended to be linked to first-year of life coverage, but the impossibility of pre-funding newborns forces an entirely different approach. Meanwhile, everybody alive has already been born, so there is less urgency. We take them up separately, and later integrate the two ends of life.

The graph is merely illustrative of the concept. Of course, we cannot predict stock market performance from past history, nor can we be sure inflation will continue at 3%. The point being made is the escrow concept allows part of the balance to remain untouched for early medical expenses but remains free to be released for designated ones, later. (The rest of the account balance has no such limitation, and thus is available for medical expenses.) The second point is the astonishing growth of a small amount of money if you give it time. And the final point is that you aren't going to get 7% passive return on your money unless you fight for it, even if you are investing in a stock market which has returned more than that for over a century. Right at the moment, it is in one of its doldrums, but even in a booming market, you have to watch out for those fees. You can even hear it prophesied that the market will have a 2% total return for the next ten years. But that isn't what is important, what's important for this kind of thinking is What Will it Do, thirty years from now? And although no one can give an answer, it has been repeatedly said that a bull market climbs a wall of worry.

To return to the nitty-gritty, income could be further enhanced by extending the time period, compounding frequently, depositing earlier, and eliminating investment fees. In the background is the implication the depositor is well advised to be frugal in his early spending, pressuring his medical providers by being mindful of frugality, himself. Any action which pushes revenue toward the left (and away from the right) helps the customer put it to work with compound interest. The customer is always right, as John Wanamaker got rich by saying. Since the particular year, the subscriber was born will probably exert more influence over his retirement affluence than anything he can manipulate, he had better do what he can. And that is the basic argument for politically trying to extend the time period for compounding. At least on that issue, single-payer advocates have a point.

True, effective net income can also be increased by restraining inflation and/or middle-men lobbyists, but we are trying to make a larger point at the moment. We should aim the system time frame to be as long as possible, most easily achieved by linking programs (childhood, adulthood, and post-retirement) together. The only thing which needs to be continuous is the account into which money is deposited. There are significant disadvantages to bigness in organizations, so if you aren't going to compound the income, I'm not sure you are wise to advocate single-payer. Our first step would thus be, to try to include the time period covered by Medicare, since that's where most medical expense seems destined to originate in the future -- along with age 25-65 since that's when significant money is usually earned. Including any time period at all helps the math, but these two periods are particularly vital.

Since Medicare comes up immediately, let's start with it.

The problems of the last year-of-life almost seem simple, compared with the problems of ensuring the health of children. For the last year of life, the funding source already exists (payroll deductions), Medicare records already exist to define the costs to be reimbursed for dying, and the transfer mechanism from one insurance company to another ("re-insurance") is already well worked out. Funding the transition presents difficult choices, but there are existing models for that sort of choice. What remains as a significant problem is to get Congress to agree to stop diverting the funds to other purposes. That issue must not be left to incumbents, but the public is pretty clear where it wants to go. That's a big problem, to be sure, but it is one easily described, and you either establish a third-party to hold the money or you don't.

By significant contrast, the beginning of life, from conception to graduation from college, is fraught with controversy and contested obligations. In the health insurance world, the funding is backward. You can't pre-fund childhood costs, particularly when you can't assign responsibility for those costs without fear of dispute. It's a medical issue, a religious issue, a political issue -- and an insurance anomaly. It's a legal tangle that everyone would like to avoid by calling it a minor cost. It isn't minor at all. Compared with the resources normally available to the parents, childbirth is a cost so large it changes the lives of everyone involved. It has the potential of destroying the largest nation on earth, China. And the second-largest, India, isn't doing so well with it, either. The rest of the developing world doesn't even try very hard.

The big social problem with prefunding obstetrics and newborn care is its present uncertainty about who legally is responsible for the bills of a newborn babe. The baby's cost can be called part of the mother's cost, and the mother's cost can be called part of the family cost, but everyone understands family relationships are in great flux at the present. About half of the marriages end in divorce or separation, too chancy an environment for insurance companies to design long-term solutions, and politicians are no clearer. In a way, the abortion controversy is part of it, where women ask for decision power but have trouble resolving the financial responsibility which would follow. Babies cannot make life decisions for themselves and are showing signs of rebelling at those their parents make for them. The trial lawyers offer solutions, but no one can afford them, particularly if they involve some exuberant jury decisions. But let's not get into all that. It's sufficient that the situation has been too unsettled to encourage lifetime solutions, whereas we are here seeking a lifetime solution because we think it might be loads cheaper.

So, our work-around approach is to take the most difficult case and seek a solution to fix it, hoping less difficult cases may be less difficult to solve. That is, we choose to assume the baby's lifetime health costs begin at birth, and the mother's obstetrical costs are her own, not the baby's. By sometimes lumping the two costs together, we arrive at a manageable line item, which can be split into two items whenever the situation warrants. That's not a solution, it is a device. Decision-making thus can be fairly satisfying all around, but it probably presumes a general acquiescence by the nation, based on its assessment of the culture.

|

Our own insurance solution assumes the social situation will stabilize. Assuming lifetime compound interest from individually small investments will approximate, over an average lifetime, lifetime average healthcare costs, its benefits will significantly exceed its costs. Compound interest income greatly expands toward the end of sixty years, so including the additional 21-26 lifetime years of children adds two doublings to the revenue. That's a significant contribution, right there. But it helps the childbirth year (8% of the cost) very little without something else added, and there are twenty more years at risk without insurance. Continuous compounding for 90 years will pay for almost anything, starting from almost nothing at birth. A lifetime of health care for $250 at birth, always seems within our reach, but is always judged unreachable.

The trick I suggest is to add, donate, transfer, or declare two extra decades of compounding as a transferable item within his HRSA, and transfer it to his grandparent or surrogate within the baby's own Health Savings Account established at birth. The condition made, is it returns to his own account when he reaches his grandparent's age. Or variations of the same idea. Compound interest greatly increases with advancing age. The grandparent couldn't take advantage of his own two doublings, but in this situation now could sure make great advantage of two extra doublings; it's worth a lot to him, nothing to the child. Notice a full average lifetime is now almost nine decades long. easily restated to be nine doublings at 7%, which is thus multiplied 500 times. The eventual evolution of Medicare into a retirement fund is only part of the idea. It brings us to the final step in the proposal: transfer it to himself at a later age and let him reap the benefit. Loan it to his grandparent, and restore it to his own generation later. Or, special index funds could be created, escrowed, and transferred at the two different ages. Created at birth, transferred at death, re-transferred to the next grandchildren generation. In various ways, this valuable unused item could be monetized and kept out of the hands of middle-men. And unfortunately, it could also be diverted, stolen or misappropriated. That means to me it should not be monetized until its destination is at hand. Take your time; get it right.

Originally published: Thursday, March 31, 2016; most-recently modified: Monday, June 03, 2019