Related Topics

Introduction: Surviving Health Costs to Retire: Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

New topic 2016-03-08 22:42:53 description

Retirement Income by Overfunding Healthcare

All right, Health Savings Accounts once appeared to be merely Christmas Savings Funds, helping people of modest means accumulate the money for their high "front-end" deductibles. The high-deductible design of health insurance paradoxically reduces the premiums of catastrophic health insurance policies. At least that's how they began; with higher deductibles on the claims, annual premiums could become lower, and the effective deductible gradually disappeared with contributions to the Christmas Fund. Subscribers to the savings accounts did run a small risk they might not deposit the full deductible before serious illness appeared, but the serious illness itself was otherwise fully covered. In fact, the effective deductible was reduced by whatever they had deposited but the premium did not rise; after a few years most of them had no out-of-pocket deductible left to pay, at all, and no extra premiums to pay for it.

So the first consequence to appear from Health Savings Accounts was first-dollar coverage without higher premiums. A small risk of small ongoing outpatient costs remained, but after a few more years even that was covered, again without raising premiums. Financial protection gradually increased with time, starting first with the worst disasters, working down to trivial ones, eventually to none at all. To repeat, without a rise in premiums, so gradually the whole package provided better coverage without increased premiums. That's why they got cheaper; the former insurance profit turned into a consumer investment. Wasteful spending was also restrained by subscribers protecting their investments, an impact which actually increases over time. With a little luck, or else starting young enough, it was possible to slide past the risky period of time, unaffected. That pretty much summarizes the medical part of the two-part plan to surpass "first dollar coverage" as fast and as cheaply as possible. The power of the Christmas Savings Fund was much greater than it appeared to be.

But after that, subscribers still had an increased cost of retirement income to worry about. It's an integral part of the medical issue because retirement costs inevitably rise with improved longevity. That's not hard to see, but if it's forty years away, it's easy to neglect. However, it becomes almost impossibly hard to get this result, if it's only two years away. That's called the "transitional problem"; everybody isn't twenty years old on the same day, and some people have simply lost their chance. Some people are already sixty-four, with variable amounts of savings. Since they can't arrange thirty years of retirement funding in a single year of saving, they have to fall back on the next-best approach. Which is to make the whole thing cost as little as possible, thereby reducing the number of people hurt by differences in age.

Fine, but how would all that theory enhance retirement income, except in pitiable amounts? What's been accomplished so far, has been accomplished collectively. The rest is up to the individual. Everyone can, for himself, make it less pitiable.

|

|

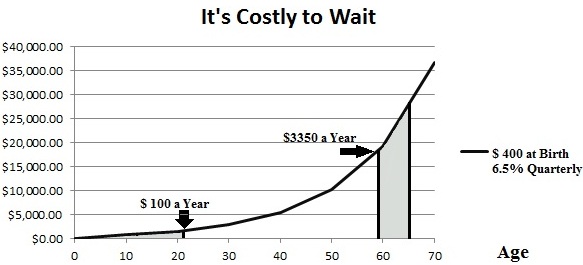

| At 6.5% compounded quarterly, it's impossible to catch up with $400 at birth, with annual deposit limits of $3350 after age 59. |

Be Frugal If You Must Spend From This Pocket. It's surely pitiable if you spend it as fast as you save it, but can build to a meaningful level in retirement if you just don't spend it. Our national leaders often say we don't spend enough. But they are talking about investing in factories, not spending on hula hoops. Nobody seriously sees any value in useless spending except a salesman. Frugality almost has to become a way of a person's life, because its impact consists of many small savings in accumulation, then multiplied by compound interest. For example, people have trained themselves to avoid paying cash for whatever insurance already covers. Here, many must deliberately re-learn to pay cash for small services, even if covered by insurance. That may sound like paying double for medical service, but its intention is to save the tax exemption for bigger things later. Let's examine that in detail, later.

Usually, premiums are set a little high to provide a margin of safety; a resulting surplus is diverted to reducing future premiums. If you think it through, the insurance company shifts its own risk onto future subscribers. (If the company goes broke, the remaining subscribers may find the risk shifted to former subscribers who dropped their policies.) Insurance companies call this a defined-term, or "term" insurance model because employer-based groups contain people of all ages, so a one-year term of insurance risk is safer for them in dealing with older subscribers. That's a good thing, by the way; you don't want your insurer to go broke.

In employment-group health insurance, surplus or deficit is made up after a year or two of "experience rating", because final health insurance risk reaches an artificial end at age 65-66, with Medicare then shouldering the remaining healthcare risk. Unfortunately, the sharp pencils of the company groups tend to make the individual (non-group) policies serve as a sort of contingency-risk fund, although employers are generally unaware they are having this effect on people who do not share their tax exemption. Nevertheless, someday, current low-interest rates must go back up to normal levels, investment income once more becoming a meaningful gain; so look for investment income to return to normal for individual policies. There are myriad reasons behind the yield curve slope, which relentlessly defeat the convenience of any Federal Reserve Chairman who wishes to continue low rates. Call it supply and demand, for shorthand.

Individual ("non-group") insurance also contains people of many ages, but people using it are expected to know how old they are. Health Savings Accounts are always individual accounts, not pooled ones. (The required pooling of risk is situated within the catastrophic health insurance, attached to every savings account.) Individual unpooled accounts offer two advantages to younger people: of a longer time horizon to work out the leads and lags, plus some savings from not subsidizing older subscribers, as employer group policies tend to do. In an HSA you subsidize yourself at a later age, which is a whole lot different.

You do share your major health risks in the insurance part, but you don't share your individually compounded savings from frugality, in the savings account. Older working people might be wise to set aside some personal savings to supplement the one-year term health insurance, adjusting for the more frequent risk of a second sickness in older people. Because the Affordable Care Act mandates the deductible, it also mandates an "out of pocket limit" to recognize the risk of a second illness coming along too soon. So Health Savings Accounts usually do the same. That's safer but raises the cost. Furthermore, interest rates have been unusually low for nearly a decade, so banks have made a habit of paying lower cash dividends longer than rising earnings can justify. However, in spite of the superficial theory that Health Savings Accounts cannot accumulate much money for retirement, demand for them has been heavy and fairness has become balanced. At present, their aggregate deposits are already reported to be over $30 billion.

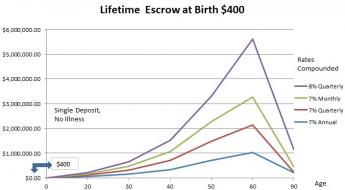

Deductibles vs. Copayments. This seems a good time to emphasize the good feature of a front-end deductible, compared with the uselessness of copayments (traditionally 20% of claims cost.) Both of them reduce premium levels, but for different purposes. Deductibles induce patient frugality, as we have noted.Perhaps not surprisingly, most new subscribers to HSA have been younger than age fifty, and forty percent have so far never made a single withdrawal from their accounts. It's hard to measure, but the aggregate small incentives of saving for retirement have resulted in 30% less spending for disease, so the size of account balances grows faster than expected in spite of the current recession. Ultimately there must be some surplus because competition will force at least some savings to be distributed to subscribers. Subscribers are nevertheless on the lookout for investments which pay more than ordinary bank savings accounts; stock index funds ("passive investing") are the most popular alternative. Please notice that all of these explorations grow out of the unusual feature that Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts are the only available form of health insurance which surrenders all termination surplus directly to the consumer, rather than return it to him via the insurance company as lower premiums. In theory, the amounts should eventually seem to be about the same, but compound interest over the fifty-year interval spreads them apart. (See the graph, above.)The purpose behind the typical 80/20 co-pay is less obvious since it is only calculated after a claim is made, or let's say after a wasteful procedure has already been performed. Repeated studies have shown it has a little net effect on premiums or service usage. Instead, it is favored by negotiators who must make quick decisions in a bargaining session, because a 20% co-pay results in a 20% reduction of premium, a 40% co-pay would result in a 40% premium reduction, etc. Co-pay has the additional perverse effect of making a second supplemental insurance policy attractive to most subscribers, including a doubling of its insurance profit and overhead.

Consequently, we favor high "front-end" deductibles, but reject copayments from insurance design. And subscribers ought to do the same.

Portability in a Larger Sense, Leading to Hidden Cost savings. The fact that HSA accounts are proving financially attractive, is surely a sign they may contain some previously unsuspected advantages, in addition to just being portable between employers. Additional portability -- between only paying for health care and paying for retirement in addition -- is more smooth and natural than we expected. Improvements in longevity reflect improvements in health care and are the natural consequence of the population getting healthier. (The saving in one compartment, is a cost for the other, with compound interest exaggerating the difference.) Furthermore, there is a consequence more evident to physicians than to patients: if you get really sick, you won't need to worry much about retirement costs, so here too a saving in one is still a cost in the other but in reverse. By far the largest accelerator to the balance is to overfund it up to the legal limit. No attempt is made in this book to claim we know what future costs will be, except to point out -- whatever they are -- increasing longevity will clearly push costs into different compartments, some upward, and some downward. It seems certain flexibility between compartments will become more desirable over time and might save considerable money. The clause in Health and Retirement Savings Accounts that any leftover tax-exempt surplus transforms into an IRA (Individual Retirement Account) when Medicare eligibility is attained, is probably the forerunner of others. More potential flexibilities are explored in this book, and advocates of other systems are invited to add features to their favorite program. In other words, at age 65, a subscriber does lose a doubly tax-exempt HSA with a surplus, but gets back Medicare plus a regular Retirement Account (IRA) in return, unless middle-men eat up the float. It's logical it would save money, but the heartening discovery is, it actually does.

The Battlefield. The HSA derives a double tax deduction in the sense that whatever is spent on qualified health service is not taxed, neither when it is deposited nor when it is spent. That appears to be a major inducement for HSA subscribers to be frugal, and the longer it continues the more it accelerates. That's in itself the main reason not to tamper with the incentive since the alternative incentive is to employ brute force to hold prices down, a probably futile gesture of amateurish administrators. Since a few dollars saved while young, compounds into many more dollars later, the double exemption is often the best investment an average person can find. It is, to say the least, an attractive alternative investment vehicle, if not a windfall.

Splitting the healthcare product into two compartments (savings account and Catastrophic health insurance) has proved particularly suitable for saving within the account for out-patient costs. Price-shopping for cheaper medical expenses seems irrelevant to truly sick persons in a hospital bed, however. Spread-the-risk insurance was inevitable for disrobed patients, whatever the related temptation for overspending. It's important for customers to be convinced the spread-the-risk quality of insurance continues but is confined to circumstances where it has no real alternative. Those professions coming from different cultures who scoff at the self-restraint of physicians are in some danger of enraging doctors into behavior everyone will regret, encouraging behavior which is being resisted. Nevertheless, some degree of slippage is inevitably part of insurance. As soon as you spread the risk, for example, it gets harder to itemize the bill fairly.

Be Careful Who Your Subsidy Partners Are. Insurance companies and hospitals both share risks with clients, and boast it reduces premiums. Young people almost always have lower costs than older ones, so it's tempting to mix a few expensive old folks with a large number of young ones in group policies. However, the client doesn't usually consider the overall effect of his choosing either a particular insurer or a particular hospital. No matter how old he is, he should want to be mixed with a lot of young clients (except premature babies).Cheaper. These and other mechanisms probably underlie the claim that HSAs are 30% cheaper. Because there are many small explanations rather than a few big ones, they will be harder to imitate. Such an accumulation, doubly tax-exempt, over a period of several decades aggregates to a surprising amount of compound interest. Money at 7% only takes ten years to double, for example. Most people would have difficulty finding a superior way to save for retirement, then by reflexly putting any spare cash into an HRSA. It's true you have to get sick to be entitled to the double deduction, and you may not survive severe illnesses with much savings. But the peace of mind of just knowing you have been covered by shrewd exertions of skillful management creates some cost-free benefit not to be scoffed at. Everybody needs a consolation in despair, and this one turns out to be powerful.The Affordable Care Act seems to have overlooked the refinements of this homily; by striving to include all the uninsured, they managed to include a large number of newborns and specialty children's hospitals, who are effectively (however reluctantly) subsidized by the rest of the community. Employer groups trying to do the same thing, necessarily avoid most people under 25 years old, who were suddenly included in population-wide averages of uninsured, by the new law. Patients over 65 may be similarly under-represented. Furthermore, about twenty cancer hospitals have been exempted from DRG constraints. Regardless of how it got composed, the ACA found it was subsidizing more than it expected, and (because they were the subsidizers) premiums for good people consequently threatened to rise more than expected, even though sometimes enjoying incomes which exceed the uninsured.

Employer groups were thus cross subsidized, but to differing degrees; outcomes were hard to predict and smaller groups proved more agile than larger demographic subgroupings. Out of these unexpected aggregate costs, arose a need to subsidize employer groups unexpectedly, and explains some unlikely favoritism for prosperous political groups originally targeted for income redistribution. In most employer groups, young people subsidize older ones; that's definitely not the same as rich people subsidizing poor ones. The detailed extent of these problems will probably not emerge until after the November elections.

Hospitals differ in their costs for similar case-mixture reasons. If you don't need a big-city tertiary hospital, you need to ask why you should pay for it by secondarily cross-subsidizing its expensive clients. This may explain some of the surprising successes and failures of HMOs, private insurance companies, and other allegedly share-the-risk groupings. Small, agile and for-profit companies seem to maneuver more readily than big non-profit ones.

"Overfunding" the Account. Therefore, enlisting patient participation extends the argument for durably separating the account from the insurance. Indeed, it makes a significant argument for overfunding the account among young people, who badly need to hear it. "Overfunding" in this case means trying to spend as little of the account as you carelessly might spend. If a considerable number of people become so-minded, a relatively realistic market price can emerge for out-patient costs. This is America, after all. That's not so true of inpatient costs, but it nevertheless provides a relative-value base for even those costs -- with a few adjustments in the regulations related to major changes in the diagnosis code employed.

Summary. So that's how we see the simple change in the payment structure into a Christmas saving account transforms a device for helping poor people afford insurance, and adds to it an incentive for the patient to be frugal for his vulnerable old age. Instead of paying to borrow money, he is paid to save it. Pinch pennies for healthcare, in order to save dollars for retirement. And then multiply it by compound interest A mutually beneficial system actually reducing medical costs, is the underlying description. It does this by providing a pathway, and an investment vehicle, for deriving meaningful retirement insurance out of unused health insurance. (This boils down to a sterner message: if you abuse the healthcare system, your own retirement will suffer.) The demographic group may not suffer, but because it's individually owned, the careless individual may shoot himself in the foot.

Resistance to Disintermediation. But, it must be noted, since this can also transform health insurance from a cost center into a revenue center, it creates some uncomfortable resistance from the financial community (because it seems to them to be a zero-sum loss). The resistance is this: financial transaction costs have declined 70% in the past ten years, so the financial community is hurting, at least compared with the Gilded Age. After all, declining prices of anything are a major reason for profitability to fall. If, in addition to attrition in revenue, a formerly insignificant income for the subscriber (interest on the accounts) transforms into an important mechanism for building up a retirement fund in six figures lasting thirty years -- it starts trouble with its zero-sum counterparty. Subscribers begin asking uncomfortable questions and making cost comparisons, at a time when the financial community sees its own income under stress. Already, there is agitation in Congress to replace buyer-beware with fiduciary advisors. The subscribers will win because they have the votes, and control the flow of funds into accounts. But it may turn out to be a slow bloody battle, notwithstanding its far more dignified potential for transforming into an attractive opportunity for both sides.The Source of Subscriber Sluggishness. When individuals compete with corporations (tax authorities and investment managers), it is usually a matter of youthful inexperience futilely competing with the experience and immortality of corporations. It seems to take a long time for young people to discover how much difference a steady, small interest rate can make to the process of converting small savings into big ones -- providing one starts early in life. Immortal corporations do have a more distant horizon and an indelible memory. But the immortality isn't as great as many think; for a glaring example, it's a comparatively rare corporation which stays in business for a hundred years. The greater advantage which a corporation has is it has been given a solitary legal mandate to make as much money as possible. The movies call that "greed" but a corporation either sticks to its business (making money) or falls out of that business, sometimes after being sued by its stockholders.

A large corporation can lose lots of money. Those who wish to penalize excessive profits should more logically favor elimination of corporate income taxes, allowing high profits and large losses both to fall upon richer individuals. The present system, allowing profits to go to stockholders at lower rates than corporate taxes would, encourages corporations to get bigger, less profitable, and to flee the country which started them. None of these outcomes is likely to appeal to populists. Since healthcare has grown to 16-18% of GDP, the present tax arrangement of health insurance probably exerts an appreciable drag on the economy.

Imposed Self-control by Escrow Accounts. Young people constantly face the competing priority of consumption, and many never do learn to restrain it in order to accumulate larger savings. Others learn but too late, after several decades of potential doubling have been forever lost. Odysseus knew this but he also understood himself, so he had himself lashed to the mast of his ship while he sailed past the temptations. The shocking truth is that very small differences in interest rates, differences which some would have you believe are trivial, accelerate savings faster than most young people ever imagine. Taxing authorities and investment companies have already learned compound interest grows best over long stretches of time, and small differences in interest rate (as little as 0.1%) are quite sufficient if continued for a lifetime. This is a simple point, but so vital we must soon devote more time to the requirement of "escrow" accounts, perhaps more aptly termed "Siren Song Accounts". Call them to lose insurance or even credit default swaps if you please, but at least recognize they impose an opportunity cost.True, about a fifth of the contribution to this scheme is provided by income tax reduction, but the line between public and private obligations to health care is already too blurred to hope for an agreement on the fairness issue. Just look at the combined state and federal tax contribution to the cost of group employer-based insurance, which probably approaches 60%. Still more important is the hidden contribution to increased longevity made by medical care. It seems hardly debatable that improving health was largely responsible for lengthening the time in retirement. The problem of outliving savings is pretty much a by-product of improving medical care; if you want one, you must cope with the other. For this reason alone, it seems entirely proper to include rising retirement costs as part of the cost of improving health care. If you want to solve the whole problem, however, you look for any solution and forget about assigning blame. Is there anyone reading this chapter who doesn't want to live an extra thirty years?True, many banks do offer Health Savings Accounts without either an attached health insurance policy or brokerage service. Both services are essential, but selecting insurance managers in these cases remains the customer's problem. You might think banks would have a similar response to the investment management of savings, except they have a complicated relationship with insurance companies they may not wish to disturb. By contrast, they also have a losing competition with investment banks, who have found cheaper ways to acquire large-sized investable funds by selling bonds and stock certificates. The time-honored method for banks to acquire funds is by dribs and drabs from the float of deposits -- quite an inefficient source, compared with $100 million bond sales. From time to time, as in the recent mortgage disaster, the government puts its thumb on the scales, and right now all banks are afraid to lose market share to competitors. Secret kickbacks may play some role in all this, so acquiring and integrating a whole company's operation seems a safer business alternative for them. One way or another, your account may be transferred to a different manager without your knowing it.

The conflicted outcome at present is for the potential HSA customer to discover which HSA vendor declines to make choices between insurance companies, but does look for ways to acquire the investment end of the business and overcharge for it, either directly or with kickbacks. In a curious twist, this pressure shifts to the customer to choose stock-pickers, whereas his best interest is usually served by choosing total-market index funds. Watch out for fees, however, which can upset any generalization about investment type. This situation can shift rapidly in the present environment since it would not be surprising for these financial behemoths to purchase market share indirectly, or else for failing stockpicker firms to sell themselves to banks of various descriptions. A much more productive approach for the small investor would be to look for a firm which will segregate accounts into "escrow, and non-escrow", leaving the choice of a high-deductible health insurer to the customer. Likewise, accounts could still be designated "captive, or self-selected", and leave the choice of investment management to the customer. It's true the average investor is often poorly equipped to make such choices but should have no difficulty in telling 1% from 8%, when (see below) the difference of one-tenth of a percent can result in a lifetime swing of $30,000. The importance of escrow accounts is described in the section which follows this one. Essentially, you can get a higher income if something forces you to shift short-term into a long-term investment.

The Importance of Small Differences in Interest Rates. To pay expenses in a stripped-down HSA, banks often charge for smallish balances, waived when the balance reaches their business break-even point, usually about $5000 per account. Similarly, investment latitude is often stratified, with larger accounts are given more choice of investments. Those are generally good arrangements because of their flexibility and elimination of conflicts of interest, but they impose some responsibility on the customer -- who must be willing to make security selections in return for possibly greater return. It's all quite understandable and suggests novel uses of the account. The best example before us is to "Overfund" it at the beginning, and use its surplus after compound interest, to supplement retirement income decades later; let's explain.

Improving the Retirement Benefit At present, the HSA law permits a maximum deposit of $3350 per year per person, with even higher limits for whole families. By constraining out-patient expenses or paying cash for them, the balance can thus build up to $5000 in less than two years, eliminating bank surcharges of roughly $50 a year by immediately reaching the waiver level. Since doing this also eliminates any remaining question whether the HSA will provide full coverage for hospital charges, it's pretty easy to endorse a $5000 investment which produces $50 a year tax-exempt income until Medicare kicks in, and then compounds it, adding more than 1% tax-free to its investment income. If the transaction then permits investment in total market indexes, paying off the investment was very wise. Let's now extend the frugal idea to more prosperous customers.

The Outer Limits of What is Possible. If an employee deposits the full limit of an HSA and makes no withdrawals from age 20 to age 65, his balance will be increased by $154,550. In fact, it should grow by more than that, possibly much more, if the income compounds. He can start with the present abnormally low-interest rate of 1%, and find annual maximum payments compound the balance to $196,225 in 45 years. With a more normal interest rate of 4%, this rises to $442,527. At 6.5% interest rate (which probably requires stock index investment to achieve), the result would be $959,760. Since the stock market for the past century has averaged 11% return, and inflation has averaged 3%, a net-of-inflation return of 8% is conceivable -- before taxes and expenses -- and so we'll set 8% as the theoretical maximum goal. $1,578,977 retirement account (at 8% net) is thus the utmost goal which is realistically achievable, adjusted for inflation. But the difference between roughly $908 thousand and $1.5 million ($650,000) is a difference still worth pondering since it identifies the maximum potential difference attributable to middle-man costs, and that's a lot. And if you think the bank is entitled to something, it probably can get compensated by compounding daily but paying compounding quarterly, and additionally by requiring deposits monthly but crediting them yearly. As far as inflation is concerned, these are uninflated numbers, both at deposit and withdrawal. That is to say, they are all in 2016 currency, and leave a generous potential profit for the manager.

Just squeezing out 6.6% instead of 6.5% makes for a final difference of $30,500, or roughly a fifth of the net (of medical outpatient expenses) deposited. Without resorting to insulting language, this large difference achieved by such a small income increment is a legitimate goal for technology improvements and management streamlining. The amount is seemingly within reach, and the consequences are worth it. So although the Standard and Poor 500 actually averaged 6.6%, and the modal return was even higher, we round it off to 6.5% in most of our illustrations. Several such small yield improvements can boost net returns by 1%, which makes an enormous difference in eventual yield after decades of compounding. That's particularly true in a compound yield curve which turns up at its far end. Since transaction costs have decreased by 70% in the past ten years, it definitely seems possible to extract an equal amount again by relentlessly pressing for it. It misjudges the public mood to say there is no room for improvement by educating the public. Right now, everybody involved would probably agree it is high time to increase the deposit limits, after several decades of their having remained stationary. That alone would significantly assist the transition from a nuisance to a central bulwark of retirement security. The financial industry wrongly misjudged this transformation to be trivial, so it's getting a little late to adjust it gracefully. Working out some examples from beginning to end, is very persuasive.

Originally published: Tuesday, March 01, 2016; most-recently modified: Monday, June 03, 2019