Related Topics

Right Angle Club: 2015

The tenth year of this annal, the ninety-third for the club. Because its author spent much of the past year on health economics, a summary of this topic takes up a third of this volume. The 1980 book now sells on Amazon for three times its original price, so be warned.

The Pity of It, Iago; Employer-basing is Mostly a Tax Gimmick

Times change. The Japanese have been defeated in "the" war. The spirit of sacrificing anything else to survive an external threat has subsided. California has become a blue state, and is fast becoming a minority-dominated one. A new generation has appeared, and unmindful of historic beginnings, has come to accept old expedients as simply the rules of the game. In particular, fringe benefits are no longer a bonus, but just a part of earnings which for some reason are tax-sheltered.

To sum it all up, Chief Financial Officers no longer feel they are cheating when they maximize tax "benefits". It's legal, isn't it? Obviously, an employee receiving a big gift finds it more welcome than paying for it himself, especially since it is tax-free and other people don't get the same treatment. Economists who have examined the matter are fairly unanimous that fringe benefits are all soon merged in the minds of employers and employees alike as "employee cost." Within a few years in a competitive environment, both sides of the gift soon treat fringe benefits as only a tax benefit, with comparable reductions in the pay packet to adjust for them. The cost of the gift soon equilibrates, only the tax deduction is a true transfer.

Nevertheless, there are economic limits, if not legal ones. Issues like Portability, Job-Lock, pre-existing conditions, and individual choice would disappear if health insurance were freed of linkage to employers since these issues are all traceable to the mandatory link between health insurance and losing your job. We really do have an employer-based system, but it has a price. Lifetime healthcare insurance policies would place considerable strain on portability and choice, so employer-basing stands in the road of multi-year insurance. Maybe, just maybe, we should reconsider the advantages and disadvantages of having it remain a gift from employers. The growing suspicion it has been the main impetus for cost escalation is worth testing.

In fact, the shareholders usually get a bigger gift than employees do. State and local corporation taxes vary, but a profitable corporation pays 38% federal corporate tax, and the total corporate tax burden approaches 50% if you include mandated sharing of other fringe benefit costs, the highest in the developed world. By defining fringe benefits as a tax-deductible cost of doing business, some major corporations effectively increase their net income by half.

|

To understand how that is possible, just look at any payroll tax stub next payday. All these features were intended to redistribute wealth, but the CFOs, turned them into shareholder advantages. Tax deductions from the pay packet total about 15% of net pay. But the employer must match most of that deduction with his own contribution, which brings him to 30%. And furthermore he pays twice as high a tax rate: about 40% tops compared with a blended individual rate of 15%, so it all adds up to 60%. Let's use the imaginary example of a $10,000 health insurance premium, where the employee gets a $1500 tax reduction, but the employer gets $3000. It's after-tax money, so the employee effectively gets $1726 and the employer $4200. For a big employer, multiply that by 10,000 employees and you get a noticeable amount of money. It's so much money you can imagine what the stock market would do, if a proposal to abolish it looked as though it might be enacted. But would you believe it -- that's not the worst of the situation.

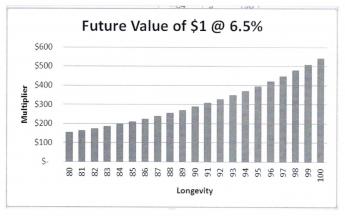

The worst is -- the employer has been given a very large financial incentive to raise the cost of healthcare. The higher the better, and shareholders ought to love it. Physicians have the same incentive because we would love to raise our fees, as Adam Smith so tersely put it in The Wealth of Nations. But at least we doctors took the Hippocratic Oath, and most of us are a little ashamed of this conflict of interest. Whereas, a stockholder controlled company has hired a manager with the mandate, to make as much profit as he legally can. Let's summarize: we have engineered a system where it is well known among CFOs that you can often make extra profits by giving a gift of health insurance to the employees. And if that isn't a tax gimmick, I don't know what would be. We have finally reached the point where the health system costs 18% of Gross Domestic Product in spite of closing 500,000 mental health beds, all of the tuberculosis sanatoria, all of the polio beds, and lengthened human longevity by thirty years. Maybe you can blame that paradox on doctors, but I doubt it.

We have simply got to stop telling fairy tales about Henry Kaiser and Liberty ships eighty years ago. This is a tax gimmick and it has to stop. I would be happy to meet with the Business Roundtable to discuss how we could stop it without crashing the stock market, but it has got to stop. My two-part proposal is pretty short, however:

Proposal : Employers should discontinue providing free health benefits to their employees, at the same time corporate income taxes should be capped at the same rates as individual income tax. The speed by which this is to take place might be determined by the Federal Reserve in response to economic conditions, but in no case longer than three years to complete the process.The competitors deserve a word, here. About half of business is made up of big business, and half is small business. Wall Street and Main Street, if you will. The opportunities which Henry Kaiser stumbled upon in 1943 mostly apply to big business, and probably much of that anomaly can be traced to the fact that bigger businesses are more likely to be profitable, and more likely to be engaged in international trade, where competitors don't get a vote. Some of the tax benefits for small business like Subchapter S, probably represent an effort by Congress to help domestic competitors without helping foreign ones.

But self-employed people, and unemployed ones, are excluded. Very likely, much of the politics of healthcare is intended to help these people, without helping small business or big business, and without helping foreign competitors. Pretty soon, you have a tangle of interests affected by removing the obvious tax inequity which Henry Kaiser is given credit for discovering. Just about everybody has something to gain, something to lose. So it begins to be impossible to say, on net balance, how much the country would be improved by abolishing it. That's particularly true, with the Affordable Care Act on trial.

Just how bad things are, is hard to say. But plenty bad enough. We know about job lock and the other features directly attached to employer-based insurance, and we decided to live with them. But the escalation of healthcare costs, and the soaring international debts used to pay for them, are becoming too much to handle. We can tolerate a lot of things, but it's not clear we can tolerate 18% of GDP devoted to healthcare, particularly if the price keeps rising. It's hard to imagine anything people would prefer to spend their money on, then on longevity. But when serious people, or at least people who take themselves seriously, start talking about euthanasia as a solution to our health cost problem, you know the costs are starting to hurt. So get this: you can only do it once, so euthanasia isn't as useful a solution as tax reform.What a Tangled Web We Weave.For the most part, only economists are familiar with the rather well-established fact that wages in the pay packet soon decline to recognize the value of other items in the total wage cost. In this case, it is the 15-20% tax reduction as a result of the Henry Kaiser tax dodge. After eighty years, news of this theory has seeped into the minds of labor unions and is slowly becoming common parlance among union membership. So inevitably, bickering about tax subsidies for poor people gradually reached the same point of recognition. Negotiators who have won an economic victory on an esoteric point, often find it difficult to restrain their boasting of it afterward.

In the case of subsidies for the poor to pay for national health insurance, the subsidy was based on whether the individual's income was a certain percent of the poverty level. When the individual's income falls in the border zone, it may make a big difference whether or not to include the tax deduction as wages. A decision on this point affected eligibility for subsidy of millions of low-wage employees of big business. And that in turn affected their personal decision whether to buy health insurance in the exchanges or to continue to get it through the employer -- which way would be cheaper? With millions of dollars at stake, it is small wonder the negotiations apparently broke up and agreed on a two-year postponement of including employees in Obamacare. Since the political makeup of Congress had changed since the law was passed, the law itself could not be adjusted to smooth out this difficulty. The implication (pretense?) has been circulated that somewhere buried in legislation there exists some relief from this situation, but it will not be effective until 2018. It scarcely seems likely a useful compromise could be devised during that time window, or during a Republican administration afterward, so stay tuned.

A related issue might also be involved in the mysterious revival of the minimum wage by union politicians. It seems possible the reasoning is that, since you can't lower the threshold for subsidies, perhaps you could raise wages to meet the threshold. Some pretty sophisticated people are apparently advising these politicians about a pretty obscure economic point. Ordinarily, the market wouldn't tolerate such manipulation, but having gone off the gold standard, perhaps it now seems possible to give it a try. All in all, the arguments for a minimum wage are so tenuous, it seems more likely that inflation is being toyed with, as a possible way to expunge indebtedness.

Originally published: Friday, July 03, 2015; most-recently modified: Friday, June 07, 2019