Related Topics

No topics are associated with this blog

Deeper Detail: Extending the Investor's Return, Simplifying His Role

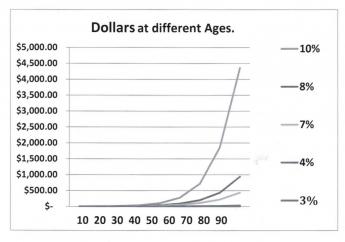

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Start by looking at what happens if you increase the interest rate from 5% to 12%, or if you lengthen life expectancy from age 65 to age 93. Stretch the limits to see what stress will do. For example, increasing the interest rate to the edge of believable gets your balance to a couple of million dollars amazingly quickly, while lengthening the time period (for that interest rate to work) even further enhances that gain. The combination of the two easily escalates the investment above twenty million. Because we are only trying to get to $350,000, reaching it suddenly seems believable.

The combination of extra time plus extra interest rate holds out a theoretical promise of paying for a lengthening lifetime of medical care, in spite of medical cost inflation. Present realities don't quite stretch that far, but finding some way to reach that level is not hard to imagine. In fact, it gets the calculation to giddy amounts so quickly it engenders suspicion, to which one answer is, we probably don't need anything like twenty million. The actuaries at Michigan Blue Cross, verified by the Medicare agency, estimate average lifetime health costs to be around $350,000 per lifetime. That's just a guess, of course, but increasing interest rates and life expectancy just a little could reach that minimum requirement. How do we go about it, and how far dare we go?

Some very credible theories sometimes disappoint us. Remember, our whole currency is based on the notion of the Federal Reserve "targeting" inflation at 2%, but in spite of spending trillions of dollars, they sometimes seem unable to achieve that target. We had better not count on schemes which require the Federal Reserve to target interest rates, because sometimes, they can't. On the other hand, if a vast army of smart people set about to nibble at various small increases in interest rates and longevity, perhaps they can make serious progress.

One person who does have practical control of the interest rate an investor receives is his own broker. For a full century, Rogen Ibbotson has published the returns on various investments, and they don't vary a great deal. Common stock produces a return of between 10% and 12.7% in spite of wars and depressions; if you stand back a few feet, the graph is pretty close to a straight line. If you search carefully, a number of brokerages offer Health Savings Accounts which produce no interest at all -- to the investor -- for the first ten years. Try earning 2% during inflation of 2%, and see what it gets you. In ten years, that approaches a haircut of nearly 100%, explained by the small size of the accounts, and by the fact that experienced customers who know better, just look for other vendors. Since the number of Health Savings Accounts has quickly grown to be more than ten million, it's time for some consumer protection. The prospective future size of these accounts should command much greater market power, quite soon. After all, passive investment should mainly involve the purchase of blocks of index funds, with annual fees of less than a tenth of a percent. Most of this haircutting is explained by the uncertainties of introducing the Affordable Care Act during a recession, and taking six years to get to the point of a Supreme Court Test to see if its regulations are legal and workable.

That's the Theory. If Necessary, Settle for Less. The rest of this section is devoted to rearranging healthcare payments in ways which could -- regardless of rough predictions -- outdistance guesses about future health costs. When the mind-boggling effects are verified, skeptics are invited to cut them in half, or three quarters, and yet achieve roughly the same result. The purpose is not to construct a formula, but to demonstrate the power of an idea. Like all such proposals, this one has the power to turn us into children, playing with matches. By the way, borrowing money to pay bills will conversely only make the burden worse, as we experience with the current "Pay as you go" method. By reversing the borrowing approach we double the improvement from investment, in the sense we stop doing it one way and also start doing the other. In the days when health insurance started, there was no other way possible. The reversal of this system has only recently become plausible, because life expectancy has recently increased so much, and passive investing has put the innovation within most people's reach. The environment has indeed changed, but don't take matters further than the new situation warrants.

Average life expectancy is now 83 years, was 47 in the year 1900; it would not be surprising if life expectancy reached 93 in another 93 years. The main uncertainty lies in our individual future attainment of average life expectancy, which we will never know, but probably could guess with a 10% error. When the future is thus so uncertain, we can display several examples at different levels, in order to keep reminding the reader that precision is neither possible nor necessary, in order to reach many safe conclusions about the average future. Except for one unusual thing: this particular trick is likely to get even better in the future because people will live longer. Even so, it is better to do a conservative thing with a radical idea.

Reduced to essentials for this purpose, today's average newborn is going to have 9.3 opportunities to double his money at seven percent return and would have 13.3 doublings at ten percent. Notice the double-bump: as the interest rate increases, it doubles more often, as well as enjoying a higher rate. If you care, that's essentially why compound interest grows so unexpectedly fast. This double widening will account for some very surprising results, and it largely creeps up on us, unawares. Because we don't know the precise longevity ahead, and we don't know the interest rate achievable, there is a widening variance between any two estimates. So wide, in fact, it is pointless to achieve precision. Whatever it is, it's going to be a lot.

|

| One Dollar: Lifetime Compound Interest, at Different Rates |

Start with a newborn, and give him one dollar. At age 93, he should have between $200 (@7%) and $10,000 (@10%), entirely dependent on the interest rate. That's a big swing. What it suggests is we should work very hard to raise that interest rate, even just a little bit, no matter how we intend to use the money when we are 93, to pay off accumulated lifetime healthcare debts. Don't let anyone tell you it doesn't matter whether interest rates are 7% or 12.7%, because it matters a lot. And by the way, don't kid yourself that a credit card charge doesn't matter if it is 12% or 6%. Call it greed if that pleases you; these small differences are profoundly important.

------------------------------------------------------------------ If that lesson has been absorbed, here's another:

In the last fifty or so years, American life expectancy has increased by thirty years. That's enough extra time for three extra doublings at seven percent, right? So, 2,4,8. Whatever amount of money the average person would have had when he died in 1900, is now expected to be eight times as much when he now dies thirty years later in life. And even if he loses half of it in some stock market crash, he will still retain four times as much as he formerly would have had, at the earlier death date. The reason increased longevity might rescue us from our own improvidence is the doubling rate starts soaring upward at about the time it gets extended by improved longevity. In particular, look at the family of curves. Its yield turns sharply upward for interest rates between 5% and 10%, and every extra tenth of a percent boosts it appreciably.

Now, hear this. In the past century, inflation has averaged 3%, and small-capitalization common stock averaged 12.7%, give or take 3%, or one standard deviation (One standard deviation includes 2/3 of all the variation in a year.) Some people advocate continuing with 3% inflation, many do not. The bottom line: many things have changed, in health, in longevity, and in stock market transaction costs. Those things may have seemed to change very little, but with the simple multipliers we have pointed out, conclusions become appreciably magnified. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve Chairman says she is targeting an annual inflation rate of 2% of the money in circulation; the actual increase in the past century was 3%. If you do nothing at 3%, your money will be all gone in thirty-three years. If you stay in cash at 2%, it will take fifty years to be all gone.

But if you work at things just a little, you can take advantage of the progressive widening of two curves: three percent for inflation stays pretty flat, but seven percent for investment income starts to soar. Up to 7%, there is a reasonable choice between stocks and bonds; but if you need more than 7% you must invest in stocks. Future inflation and future stock returns may remain at 3 and 7, forever, or they may get tinkered with. But the 3% and 7% curves are getting further apart with every year of increasing longevity. Some people will get lucky or take inordinate risks, and for them, the 10% investment curve might widen from a 3% inflation curve, a whole lot faster. But every single tenth of a percent net improvement will cast a long shadow.

But never, ever forget the reverse: a 7% investment rate will grow vastly faster than 4% will, but if people allow this windfall to be taxed or swindled, the proposal you are reading will fall far short of its promise. Our economy operates between a relatively flat 3% and a sharply rising 4-5%. In other words, it wouldn't have to rise much above 3% inflation rate to be starting to spiral out of control. Our Federal Reserve is well aware of this, but the public isn't. A sudden international economic tidal wave could easily push inflation out of control, in our country just as much as Greece or Portugal. As developing nations grow more prosperous, our Federal Reserve controls a progressively smaller proportion of international currency. Therefore, we could do less to stem a crisis that we have done in the past.

To summarize, on the revenue side of the ledger, we note the arithmetic that a single deposit of about $55 in a Health Savings Account in 1923 might have grown to about $350,000 by today, in the year 2015, because the stock market did achieve more than 10% return. There is considerable attractiveness to the alternative of extending HSA limits down to the age of birth, and up to the date of death. It's really up to Congress to do it. If the past century's market had grown at merely 6.5% instead of 10%, the $55 would now only be $18,000, so we would already be past the tipping point on rates. In plain language, by using a 10% example, $55 could have reached the sum now presently thought by statisticians -- to be the total health expenditure for a lifetime. But by accepting a 6.5% return, however, the same investment would have fallen short of enough money for the purpose. Like the municipalities that gambled on their pension fund returns, that sort of trap must be avoided. Things are not entirely hopeless, because 6.5% would remain adequate if our hypothetical newborn had started with $100, still within a conceivable range for subsidies. But the point to be made provides only a razor-thin margin between buying a Rolls Royce, and buying a motorbike. If you get it right on interest rates and longevity, the cost of the purchase is relatively insignificant. That's the central point of the first two graphs. For some people, it would inevitably lead to investing nothing at all, for personal reasons. Some of the poor will have to be subsidized, some of the timid will have to be prodded. This is more of a research problem than you would guess: a round-about approach is to eliminate the diseases which cost so much, choosing between research to do it, or rationing to do it. Right now we have a choice; if we delay, the only remaining choice would be rationing.

Commentary.This discussion is, again, mainly to show the reader the enormous power and complexity of compound interest, which most people under-appreciate, as well as the additional power added by extending life expectancy by thirty years this century, and the surprising boost of passive investment income toward 10% by financial transaction technology. Many conclusions can be drawn, including possibly the conclusion that this proposal leaves too narrow a margin of safety to pay for everything. The conclusion I prefer to reach is that this structure is almost good enough, but requires some additional innovation to be safe enough. That line of reasoning will be pursued in Chapter Fxxx.Revenue growing at 10% will relentlessly grow faster than expenses at 3%. As experience has shown, it is next to impossible to switch health care to the public sector and still expect investment returns at private sector levels. Repayment of overseas debt does not affect actual domestic health expenditures, but it indirectly affects the value of the dollar, greatly. Without all its recognized weaknesses, a fairly safe description of present data would be that enormous savings in the healthcare system are possible, but only to the degree, we contain next century's medical cost inflation closer to 2% than to 10%. The simplest way to retain revenue at 10% growth is by anchoring the price leaders within the private sector. The hardest way to do it would be to try to achieve private sector profits, inside the public sector. This chapter describes a middle way. Better than alternatives, perhaps, but nothing miraculous. For the full whammy, you will have to read chapters Three and Four.

Cost, One of Two Basic Numbers. Blue Cross of Michigan and two federal agencies put their own data through a formula which created a hypothetical average subscriber's cost for a lifetime at today's prices. The agencies produced a lifetime cost estimate of around $300,000. That's not what we actually spent because so much of medical care has changed, but at such a steady rate that it justifies the assumption, it will continue into the next century. So, although the calculation comes closer to approximating the next century, than what was seen in the last century, it really provides no miraculous method to anticipate future changes in diseases or longevity, either. Inflation and investment returns are assumed to be level, and longevity is assumed to level off. So be warned. This proposal, particularly with merely an annual horizon, proposes a method to pay for a lot of otherwise unfunded medical care. The proposal to pay for all of it began to arise when its full revenue potential began to emerge, rather than the other way around. If the more ambitious second proposed project ever works in full, it must expect decades of transition. Perhaps that's just as well, considering the recent examples we have had of being in too big a hurry. Rather surprisingly, the remaining problem appears mainly a matter of 10-15% of revenue, but all such projection is fraught with uncertainty.

Revenue, The Other Problem. The foregoing describes where we got our number for future lifetime medical costs; someone else did it. Our other number is $132,000, which is our figure for average lifetime revenue devoted to healthcare. That's the current limit ($3300 per year of working life) which the Congress itself applied to deposits in Health Savings Accounts. No doubt, the number was envisioned as the absolute limit of what the average person could afford, and as such seems entirely plausible. You'd have to be rich to afford more than that, and if you weren't rich, you would struggle to afford so much. To summarize the process, the number was selected as the limit of what we can afford. If it turns out we can't afford it, this proposal must somehow be supplemented. The provision made for that predicament is we will then have to jettison one or two major expenses, the repayment of our foreign debts for past deficits in healthcare entitlements, or the privatization of Medicare. That would leave us considerably short of paying for lifetime health costs, but it might actually be more politically palatable. It's far better than sacrificing medical care quality, at least, which to me is an unthinkable alternative, just when we were coming within sight of eliminating the diseases which require so much of it.

Originally published: Thursday, June 04, 2015; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 16, 2019