Related Topics

Customs, Culture and Traditions (2)

.

Philadelphia's Fourth Century: Revival or Relapse?

Novelists, sociologists, playwrights, financiers, historians, poets -- and others -- have described and explained the rise and fall of Philadelphia. Each of them is a little bit right, and a little wrong. Philadelphia is hidden, but it isn't hiding.

What Other House?

Before the First World War, it was common for prosperous families to have two houses, like migrating birds. There was the big house in center city and a second place to go in the summer to get away from typhoid and malaria. In the early days before municipal water departments, sources of clean water for home use and sewage disposal often dictated the location of such annual migrations. In time, a wider variety of destinations appeared. Summer arrangements might be a summer cottage on a lake or a mansion in Bar Harbor. Friendly local Indians and good land for fresh vegetables or milk cows made an attraction. Usually, there was some sort of recreational attraction, perhaps a summer hotel where the family went every summer, located along a railroad for easy commuting. Along the East Coast, it was common to own a beach house along the Jersey shore, and for fashionable people, it was common to have a summer place along the Main Line. Germantown was the first summer colony, started by the Allen family and soon followed by the Chews at Cliveden, who also had a house on Third Street next door to George Washington, and to Powell, the Mayor of the city. There were Germans in Germantown, of course, but they were not in the same circle, any more than the "permanent residents" of the New Jersey barrier islands mix in with the "summer folk", today. If you look at the big houses along Spruce and Pine Streets, you will see little neighboring houses in the next-door alleys. Sometimes these little houses had three rooms on three floors and were called "Father, Son, and Holy Ghost" houses. Sometimes these houses were for servants, sometimes for local tradesmen.

The implication was that if you had two houses, you must be rich. That's sort of true, but lots of families in Philadelphia had lived in the region for many generations, and had accumulated lots of real estate for the various cousins of a shrinking family. In a sense, a greater portion of Philadelphia savings was locked into this real estate, than in other cities. And there were quicks. One of the traditions of the Philadelphia political machine was to have a dinky little house in some working-class district, but a very large and opulent place at the shore, perhaps in Longport, N.J. It probably isn't necessary to describe the reasons for this.

It later turned out that the geographical size of the city was to make a significant difference. In a small village, there is little difference between the town and the countryside, but after a while, significant differences in taxes appear, particularly when our system of government begins to encourage federal, state and local taxes to become the legal or traditional province of a particular level of government. The tendency was for taxes to focus on government services from which people would be reluctant to flee. If people lived in the city for the schools, school taxes were applied to real estate. The federal system of dependence on income taxes, on the other hand, reflected an indifference to where you happened to live. This started a cat and mouse game among municipalities, states and counties, which unfortunately contributed to the direction of tax flight, when there appeared to be a reason to flee.

|

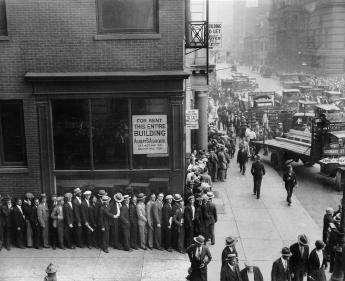

| Depression of the 1930s |

During the Depression of the 1930s, that new threat appeared. Maintaining two houses soon seemed a needless extravagance, and it made sense to sell one of them. At that point, a choice had to be made, and the advent of the automobile made it entirely practical to live in the suburbs and commute to the city. A small town found it made little difference, but a medium-sized city gave the suburbs an attractiveness. In the case of Philadelphia, the city-county consolidation widened the geographical reach of city taxes, before taxes and land values reached the inviting cliff where they abruptly fell to rural levels. By that time, clean water and friendly Indians were less important than taxes and upkeep. Some people had very bad luck in the Market, sold the big house, and moved into the little house behind it. More often than not, the big, house was converted into apartments or just plain torn down, or else it fell into shabbiness and the whole neighborhood deteriorated. After twenty years, everything got so bad in Society Hill, that you could buy any one of the mansions for $1500. It was a spiral, of course, and although you could buy a house for $1500, and resell it twenty years later for a million, during the intervening twenty years it was worth your life to go out on the street at night. Or so it seemed until Richardson Dilworth built a brand-new mansion on 6th Street, and Society Hill started its revival. So, with this little bit of real estate history, you ought to be able to summon up the tolerance to smile, when a senior partner of a law firm at a party tells you, "Philadelphia declined because everybody had two houses, and sold one of them." Not exactly everybody, but mostly everybody in the leadership did.

|

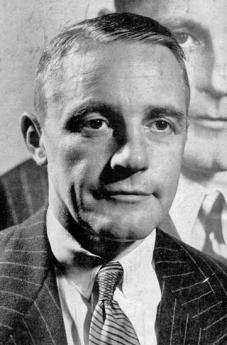

| Richardson Dilworth |

In fact, that was seemingly true for everybody, because the cohesiveness of Philadelphia culture led the followers to follow. But there was the next stage, after that. Bargain hunters found their bargains, word spread among immigrants from the South, and mansions turned into slums. To some extent, this migration was balanced by a white migration to the South, seeking cheap land and fleeing expensive union labor. Before long, air conditioning made this a natural, bearable counter-migration. In colonial days, just about everybody had a summer house for mainly health reasons, but now there was a new force causing people to relocate entirely in the suburbs. The tax cliff created by the city-county consolidation artificially raised city land values in anticipation of expanding settlement. It suddenly became cheaper to relocate or rebuild an entire facility just over the city/county line, in accordance with newer concepts of one-story buildings instead of three-story factories near a waterfall. And then a new way of life grew up around this necessity, with only the leaders returning to the city for banking, clubs, and opera "during the season". Invisibly, sanitation and air conditioning had removed the economic reason behind the former social structure, but permanent Philadelphia residents continued its customs while the Gilded Age was invisibly making it all a little silly. But hit it with depression, ruin the industrial base supporting it, and then watch it disintegrate. Housing patterns didn't cause the problem, but new ones certainly made it hard to recover the good old ways, once they disappeared.

Originally published: Saturday, July 26, 2014; most-recently modified: Friday, June 07, 2019