Related Topics

...Trying Out the New Constitution

George Washington's first term as President was much like a continuation of the Constitutional Convention, with many of the same participants.

Intrigues, At the Highest Levels

|

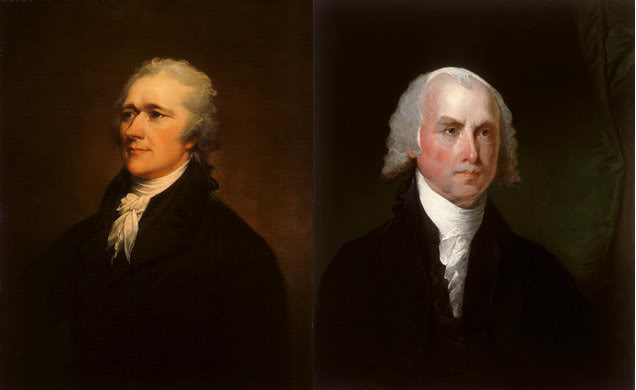

| Alexander Hamilton and James Madison |

EVOLVING scholarship now suggests the ideas and driving vigor behind the Constitution were mainly Washington's, with young Madison mainly his leg man. Young Alexander Hamilton was a second devoted agent of Washington, easily recruited after his earlier relationship as the General's chief aide and assistant during the Revolution. These three made things happen. Madison seems to have begun the relationship absorbed with advancing his place in the Virginia dream of the Potomac River: future gateway to the West and main highway of the nation. Hamilton was ambitious as well, perceiving early where the Industrial Revolution was likely to take America. He was not landed gentry. He had aristocratic ambitions, but they grew out of an orphaned boyhood spent in a Caribbean counting-house; above all, Hamilton was a risk taker and a climber. As we now know the different paths they eventually took, we see they were very different. But at the beginnings of the Constitution, they were both Washington's boys, following Washington's orders, advancing his vision.

The Potomac vision was just between Madison and the General until Hamilton eventually put it into a deal, traded for the location of the national capital, at a famous dinner party in New York hosted by Tomas Jefferson. In the meantime, the two younger men advanced Washington's long-range goals in different areas and different parts of the country. Throughout the early years, Washington maintained his natural aloof dignity. A better idea of what he was seeking emerges from how he acted. Start with his being aroused from plantation retirement by Shay's Rebellion.

|

| Daniel Shay |

Daniel Shay was a leader of 1200 rebellious farmers in central Massachusetts who in 1786 stirred up concern about chaotic government by making it worse, surrounding the debtor's courthouse in Springfield Mass. and threatening to raid the local armory to overthrow the Massachusetts government. Shay's rebellion was eventually put down but only after two years of fighting which thoroughly frightened local citizens. The rest of the country had some sympathy with a former captain in the Revolutionary War who lost his property because of currency shortages very similar to the ones that started the Revolution. Regardless of earlier rights and wrongs, the public now demanded a government which could maintain law and order. Washington was particularly upset by Shay's Rebellion because of its resemblance to the earlier revolt of the Pennsylvania Line. He continued to be blistered by the Continental Congress' inability to raise troops and pay them, inflicting hardships on the patriots Congress had once begged to protect them. Washington wrote dozens of letters around the country protesting the sorry situation and privately set about to recruit people like Madison and Hamilton to help. Madison's initial task was to recruit the Virginia Legislature and the Virginia congressional delegation to devise necessary legal provisions that would make this country a fit place to live. Washington's position in public opinion could not be resisted; he almost invariably got what he wanted. But if he could have read a letter written by Thomas Jefferson at the time, he would have had a warning that important people disagreed with him. Said Jefferson:

"A little rebellion now and then is a good thing . . . .It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government... God forbid we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion. The people cannot be all, and always, well informed. The part which is wrong will be discontented, in proportion to the importance of the facts they misconceive. If they remain quiet under such misconceptions, it is lethargy, the forerunner of death to the public liberty . . . . and what country can preserve its liberties, if its rulers are not warned, from time to time, that this person preserves the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms. The remedy is to set them right as to the facts, pardon and pacify them. What signify a few lives lost in a century or two? The tree of liberty must be refreshed, from time to time, with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure."

|

| Thomas Jefferson, 1787 |

Let's jump ahead. Washington is now our first president, confronted with our ships and sailors under attack by the Barbary Pirates."Would to Heaven we had a navy to reform those enemies to mankind or crush them into non-existence," Gen. Washington wrote in 1786. The nation built that navy largely because the pirates' hostage-taking and escalating ransom demands became politically unbearable. The ships were built in time, and in one of history's great ironies, it was President Jefferson who gets credit for subduing the pirates on the Shores of Tripoli.

|

| General Sullivan |

Throughout Washington's long career it became evident that whenever America developed conflicts in the neighborhood, the enemy's uniform response was to stir up the backwoods Indians to assassinate the settlers. Andrew Jackson is the President who is most famous for responding by confronting whole regions of Indians with the choice of extermination or eviction to lands further west, but Washington was well aware of the realities of the frontier. In response to British-inspired Indian massacres, while he was at Valley Forge, Washington dispatched General Sullivan to march against the Iroquois and exterminate them. There is legitimate doubt the settlers around Wilkes Barre in the Wyoming Valley had any right to be there, but Washington knew that above all else, a leader of a country is expected to protect it.

The most dramatic illustration of Washington's idea of a central government came in the case of the Whiskey Rebellion. When Hamilton persuaded him to impose a tax on whiskey, the corn growing frontiersmen around Pittsburgh started a rebellion against the tax. The old General's reaction was prompt and violent. Riding his horse at the head of 1500 militia, Washington marched across Pennsylvania to put an abrupt end to such ideas of defiance against his new system of proper government. He made a great show of pardoning the intimidated farmers, but he left them with no mistaking that George Washington meant business. And still, there was a warning if he could only see it. Albert Gallatin, who was to be Jefferson's future Secretary of the Treasury and thought the leader in everything economic, was one of the leaders of the Whiskey Rebellion. To see the hand of Jefferson or Madison in this affair is not alarmist.

Washington wanted a strong central government. One that would pay its troops and keep its promises, collect its taxes and defend the coasts. The rest of this mechanical formula called the Constitution was left for Madison to work out. Hamilton persuaded him that a country had to be rich and strong to be able to protect its citizens, so Washington went along with the Bank, and the Report on Manufactures. He agreed with anything Madison proposed in the way of process and balances of power. What Washington wanted of a country were law and order. When Madison eventually started talking like Jefferson, Washington never spoke to him again.

Originally published: Wednesday, December 03, 2008; most-recently modified: Wednesday, May 22, 2019