0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Prohibitory Act of the British Parliament -- 1775

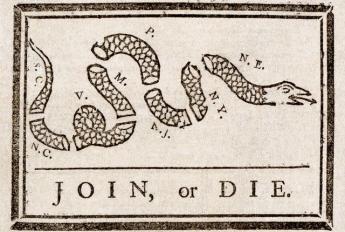

This is the British Act which started the Revolutionary War. The two Legislative bodies should have known better than to react in haste, but the British Parliament in London and its opponent the Continental Congress in Philadelphia -- started the Revolutionary War. Apparently Lord North issued the Prohibitory Act and John Adams responded to it, but the real hotheads were Charles Townsend and William Bradford.

This is the British Act which started the Revolutionary War. The two Legislative bodies should have known better than to react in haste, but the British Parliament in London and its opponent the Continental Congress in Philadelphia -- started the Revolutionary War. Apparently Lord North issued the Prohibitory Act and John Adams responded to it, but the real hotheads were Charles Townsend and William Bradford.

As usual, invisible laymen did the legwork for the events politicians take credit for. As if taking credit for starting a war is something you want. Charles Townshend and William Bradford are not now known for stirring up the Revolutionary War, one at a mansion in Britain, and the other at the London Coffeehouse in Philadelphia. They are forgotten, while Lord North of the Admiralty and John Adams of Massachusetts get credit for first writing the fearsome Prohititory Act of Parliament, and then answering it with defiance and warlike privateering-- it was just what they were looking for. Admiral Howe was dispatched to put the colonists in their place, and Adams knew the privateers were ready to sink British ships. In fact, privateers eventually caused more deaths among the British than soldiers were killed, so the New Englander knew what he was doing. And Great Britain eventually lost the war, so maybe North didn't.

In any event, the pacifist Quakers whose assent was crucial put up little opposition for a conflict the British had clearly started. And the legal pretext was that armed rebels' only choice was to switch from "Taxation without Representation" which was the slogan for Lexington and Concord, to "Independence" which carried a lesser punishment, far into the future. Opposition to war was anyway undermined when the enemy has attacked you. The great miscalculation was to think George Washington didn't have a chance against the greatest war machine in the world. That is, Adams knew 3000 miles of ocean were on his side. And he knew that even the Quakers could see that hanging for treason was worse than negotiating a treaty between two nations about boundaries. Adams was one of the few lawyers in America, but he immediately saw this distinction and how to exploit it. Besides, he probably was a little bit crazy, himself. North only made one mistake in losing the war, but how could he anticipate that?

Obamacare's Constitutionality

|

| President Barack Obama |

Any idea of a smoothly orchestrated introduction of the new law was jarringly interrupted by the U. S. Supreme Court, which granted a hearing to a complaint by 26 State Attorney Generals, that the ACA Act was unconstitutional. It was big news that the whole Affordable Care Act might be set aside without selling a single policy of insurance. The timing (before the Act had actually been implemented) served to guarantee that the constitutional issue, and only that issue, would be discussed at this Supreme Court hearing. By implication, there might be more than one episode to these hearings.

While many could have declaimed for an hour without notes, about difficult issues perceived in the Obama health plan, questioning its constitutionality had scarcely entered most minds. Then of a sudden, near the end of March 2012, a case testing the constitutionality of mandatory health insurance was granted certiorari and very promptly argued for three full days before the U.S. Supreme Court. Twenty-six state attorneys general brought that case, so it was not trivial. In jest, one Justice quipped he would rather throw out the whole case than being forced to spend a year just reading 2500 pages of it. But Justices are practiced in the art of quickly getting to the heart of a matter; it soon boiled down to one issue: was it constitutional for Congress to force the whole nation to purchase health insurance? Is there no limit in the Constitution about what the federal government can force all citizens to do, even though the federal government itself is severely limited in scope? Even though the Tenth Amendment states that anything not specifically granted to the federal becomes the province of the states? Would a people who fought an armed revolution for eight years over a 2-cent tax on tea, now consent to a much larger requirement which it was not constitutionally authorized to impose? Most people finally wrapped their heads around some formulation of this non-medical concept to a point where they vaguely understood what the Judges were arguing about. This was beginning to look like a topic where We The People made a covenant with our elected leaders, and reserve the sole right to change it.

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

|

| Tenth Amendment |

The Constitution describes a Federal system in which, a few enumerated powers are granted to the national government but every other power is reserved to the state legislatures. The Constitution had to be ratified by the states to go into effect, and the states had such strong reservations about the surrender of more than a handful of powers that they would not ratify the document unless the concept of enumeration was restated by the Tenth Amendment. If states could not be persuaded of the need for a particular power to be national, they might refuse to ratify a document which enabled permanent quarrels about the issue. That wariness explains why The Bill of Rights goes to the extra trouble of declaring certain powers are forbidden to any level of government.

Separation of powers further explains why Mr. Romney's mandatory health insurance plan might be legal for the Massachusetts legislature but prohibited to Congress. After Chief Justice Roberts got through with it, whether that truly remains the case will now depend on whether it is described as a tax, a penalty, a cost, or whatever, and only if the U.S. Supreme Court later agrees that was a proper definition. Because -- to be considered a tax it must be too small to be considered coercion. The law itself apparently does not underline this distinction in a way the Justices felt they could approve. Indeed, while Mr. Obama in his speeches firmly declared it was not a tax, later White House "officials" declared it might be. There was agreement the Federal government could tax, but no acknowledgment that taxes might have any purpose other than revenue.

Under circumstances widely visible on television, however, it was clear that the House of Representatives had been offered no opportunity to comment on this and many other points in this legislation. To a layman, that fact itself seems as clear a violation of constitutional intent as almost any other issue, since the Constitution indicates no idea was ever contemplated that any President might construct laws, nor like the courts, interpret their meaning. The first three Presidents repeatedly raised the question of whether they had the authority to do certain things we now take for granted. And Thomas Jefferson was similarly boxed in by a clever Chief Justice, who said, in effect, Agree to This Decision, or be Prepared to Get a Worse One. The Constitution says it is the function of the Executive branch to enforce the law, "faithfully". Presumably, all of the thousands of regulations issued by the Executive Branch under this law must meet the same test.

Given that the Justices now hold it constitutional for the federal Congress to mandate universal health insurance, based on some authority within taxation, the immediate next issue is paying for it. Millions of citizens, usually young and healthy but sometimes for religious reasons, do not want to buy health insurance and would be forced to do so by this law because the only available alternative is to pay a revenue tax. The purpose of including them is to overcharge people who will predictably under-use community-rated insurance, and thus enable the surplus to reduce costs for those who do want to buy health insurance. (Here, the Court had the pleasure of reducing an unusually opaque law to an unusually succinct summary.) To avoid the charge of a "taking", the Administration must either surrender on the universal mandatory point or else surrender the level premiums of community rating. The lawyers for the complaining attorneys general laid great stress on this particular issue in their arguments, and it occasioned much of the discussion from the bench. However, until the law is in action there is as yet no cause for damages.

Here it will depend on whether you call it a permissible activity for Massachusetts or for the Federal government. The Constitutional point seems to be that it is a legitimate Federal power to tax for the "general welfare", so it now becomes essential to know if the taxes for noncompliance in Obamacare are really a penalty. The Justices seemed to be questioning whether the whole scheme would collapse with the forced subsidy eliminated, and because of that be deemed to have been a "general welfare purpose" adequate to meet the constitutional requirement of a permissible enumerated purpose. Lawyers can generally find such a defined purpose in the words of the Constitution, even if they have to dip into the penumbras and emanations of the words. So the question might just devolve into whether a majority of the Justices wish to declare the penumbra to be within the enumerated powers of Congress. To all of this, the lawyers for the attorneys' general reply that such an enumerated power is impossible because there is no limit to what could be done by this method. Congress would then be allowed to mandate that everyone eat broccoli for dinner, or buy a General Motors car in order to pay for the deficits of rescuing that company from bankruptcy. Almost anything could be mandated by establishing a penalty called a tax; including a mandate that everyone buys a product in order to pay for the deficits of mandating it, illustrates there exists at least one circularity of enumerating something like a power of Congress. According to this reasoning, mandated health insurance cannot, therefore, be an enumerated power of Congress, either now or at any time in the future. The sort of speculative law outlined in this paragraph is exactly the sort of thing the Supreme Court dislikes and shows the utility of denying access to the courts to anyone who cannot claim "standing", defined as a claim of actual injury from a law.

The Justices undoubtedly had to weigh the fact that the American public has a strong distaste for this sort of convoluted reasoning, which sounds like a convention of Jesuit priests having fun. On many other occasions, however, the public has accepted the judgment of people it hired to understand this sort of thing; that's called respect for the law. Eighty years ago in the Roosevelt court-packing case, there was the same sort of collision between the Court and the President, and the Court knuckled under even though the public supported the Court. In both cases, the Court seemed to be yielding to the President, with the unspoken compromise that the President would not pursue his earlier course with quite so much vigor. Since the really central 1937 question of overturning the Interstate Commerce clause ("Commerce among the several states") was left unaddressed, the velvet glove might yet contain an iron fist.

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

|

| Spirit of 76' |

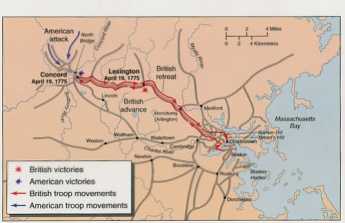

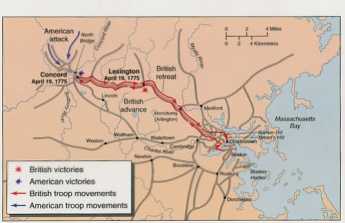

The American colonies were growing too big, too fast, and the British Empire had too many international distractions, to have smooth relationships across three thousand miles of ocean, using uncertain communications available in the late Eighteenth century. Friction and misunderstanding were inevitable without far more statesmanship than either side thought was necessary. So, when the Continental Congress dispatched George Washington to Boston with troops to defend rebellious Massachusetts at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, it was hard for the British to believe the colonists were merely helping out one of their distressed neighbors. It seemed in London that the thirteen colonies had united, formed not only an army but a government, and gone to war. In December 1775 England passed the Prohibitory Act, essentially declaring war, and organized a huge invasion fleet to put down the rebellion. It now seems hard to understand the first notice the Americans had of this huge over-reaction was a private letter to Robert Morris from one of his agents in March 1776; no warnings, no negotiations, no attempt to investigate problems and correct them. The British just sent a fleet to settle this problem, whatever it was. It's all very well to say the Americans should have known they were playing with fire. They didn't see it that way; they were being self-reliant, responding to attack. In June 1776 British patrol frigates were skirmishing in the Delaware River; late in the month, British troops landed on Staten Island. The American reaction to all this was a muddle of confusion. A few were delighted, most of the rest were amazed or appalled.

Although the deeper strategic origins of the American Revolution are subtle, complex, and controversial, there is far less muddle about what happened on July 2, 1776, publicly proclaimed two days later. Adopting a resolution written by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, the Thirteen Colonies stated they had now clarified their goals in the controversy with the British monarchy. For a year before that, the Continental Congress had been corresponding with each other and meeting in Carpenters Hall with the goal of achieving representation in the British parliament -- "No taxation without representation". The model for most of them was based on the Whig agitation for Ireland -- for a local parliament within a larger commonwealth. But the passing of the British Navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then the actual appearance of seven hundred British warships in American waters showed that not only was Parliamentary representation out of the question, but King George III was going to play rough with upstarts. The new goal was no longer just representation, it was independence. If we were going to resist a military occupation at the risk of being hanged as traitors, we might as well do it for something substantial. The meeting had a number of Scotch-Irish Princeton graduates, whose basic loyalty to England had long been divided. Pacifist Pennsylvania, chief among the wavering hold-outs, was mostly won over by its own Benjamin Franklin, who was optimistic the French would help us. Even so, both Robert Morris and John Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration; Franklin persuaded both to abstain by absence, which created a majority of the Pennsylvania delegation in favor. That's a pretty slim majority for a crucial decision. Franklin was soon dispatched back to Paris to make an alliance; Washington was dispatched to hold off that British army in the meantime. Jefferson was designated to write a proclamation, which even after editing is still pretty unreadable beyond the first couple of sentences. Meeting adjourned. This brief account may not qualify as a serious examination of the causes of the American Revolution, but it comes close to the way it seemed to the colonist in the street.

|

| Colonist's Complaint |

The rebels then spent eight years convincing the British they were serious and have been independent ever since. But, just a minute, here. Reflect on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers even waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had a big nerve implying the whole Revolution was his idea. What's more, there's a viewpoint that New England subsequently had to endure a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation because loud talk from New England still made the rest of the country nervous. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging others along with it. Rather, it was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine. When Independence was finally declared the goal, many of Philadelphia's leading citizens moved to Canada.

New England had started hostilities and was about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What New England and the Scotch-Irish needed were WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. Virginia was incensed about its powerlessness against British mercantilism, especially the tobacco trade. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing dependency on the British homeland, without a sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. It was perhaps unfortunate New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a military confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming. Without support, New England was likely to be torched, as Rome once subdued Carthage.

And the last hope for an alternative of flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, had stepped off the boat a year earlier. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, arrived with the news he had finally had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He was a man who quietly made things happen, carefully selecting his arguments from amongst many he had in mind. In retrospect, we can see that he held the idea of Anglo-Saxon world domination as far back as the Albany Conference of 1745, and could even look forward to America outgrowing England in the 19th Century. His behavior at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 strongly suggests he never completely gave up that long-term dream. Just as Edmund Burke never gave up the idea of Reconciliation with the Colonies, Benjamin Franklin never quite gave up the idea of Reconciliation with England. While John Dickinson and Robert Morris resisted the idea of Independence down to the last moment, Franklin took a much longer view. For the time being, it was necessary to defeat the British, and for that, we needed the help of the French. In 1750, America joined with the British to toss out the French. And then in 1776, we joined the French to toss out the British. Franklin didn't always get his way. But Franklin was always steering the ship.

Pennsylvania: Browbeaten Into Joining a War

|

| Battle of Lexington |

In April 1775, the colonial militia were shooting it out with British soldiers at Bunker Hill and Lexington/Concord. If you include December 16, 1773, Boston Tea Party, Massachusetts had been fighting the British for almost three years before July 4, 1776. It had never been absolutely clear to Pennsylvanians just what they were fighting about in New England, beyond the fact that a considerable store of gunpowder was hidden in Lexington and Concord and British soldiers had been sent to confiscate it, along with those two trouble-makers, Samuel Adams and John Hancock. The militiamen behind the trees were just as British as the soldiers were, and their short slogan of fair treatment was to elect representatives to any Parliament which claimed a right to tax them. Snubbed by a high-handed King, they got his attention by shooting back when the King tried to enforce laws they had not had a chance to vote on. Seeing your neighbors shot soon clarifies your options. Other colonies, especially Pennsylvania, Delaware and South Carolina, were slower to anger about either taxation or representation, worrying more about the motives of unstable leaders in Massachusetts like Samuel Adams, and content to stall while British Whigs led by Edmund Burke and the Marquess of Rockingham tried to civilize the king's ministry. Besides, the British were not attacking Pennsylvania.

To be fair to the hot-headed New Englanders who were apparently stirring up so much unprovoked trouble, a better case could have been made against the heedless British ministry, and New England lawyers should have made it. Following the Boston Massacre, there was genuine alarm among lawyers like John Adams that King George was eroding historic legal rights achieved over several centuries, indeed, preferentially undermining them more for mere colonists than for U.K. citizens with a vote. The Navigation Acts of the British government, in particular, were offensive to American colonists; randomly chosen representatives on juries proceded to render them unenforceable with a wide-spread refusal to convict. They were employing William Penn's strategy of "Jury Nullification", and better acknowledgment of its legal history was sure to make a favorable impact on Philadelphia minds. Somehow, the Boston legal community felt this line of argument was too specialized to be effective, or else shared the alarm of their enemy the British Ministry that Jury Nullification in the hands of the public could be too hard to control. John Adams had made a particularly famous defense of John Hancock who was being punished with confiscation of his ship and a fine of triple the cargo's value. Adams was later singled out as the only named American rebel the British refused to exempt from hanging if they caught him. As everyone knows, Hancock was the first to step up and sign the Declaration of Independence, because by 1776 there was also widespread colonial outrage over the British strategy of transferring cases to the (non-jury) Admiralty Court. Many colonists who privately regarded Hancock as a smuggler were roused to rebellion by the British government thus denying a defendant his right to a jury trial, especially by a jury almost certain not to convict him. To taxation without representation was added the obscenity of enforcement without due process. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the newly created United States, ruled in 1794 that "The Jury has the right to determine the law as well as the facts." And Thomas Jefferson built a whole political party on the right of common people to overturn their government, somewhat softening it is true when he saw where the French Revolution was going. Jury Nullification then lay fairly dormant for fifty years. But since the founding of the Republic and the reputation of many of the most prominent founders was based on it, there may have seemed little need for emphasis of an argument any modern politician would seize with glee.

|

| Bunker Hill |

At that time, only a third of colonists were in favor of fighting about it, and a third was entirely opposed. Samuel Adams himself had written his supporters that it would be best to hold back until greater revolutionary support could be gathered. Unfortunately, in the minds of the British ministry, hostility had already escalated irrevocably when the Continental Congress in June 1775 created the Continental Army and dispatched George Washington to Boston to join the fight. This was probably the moment when war became inevitable in the collective mind of the British Parliament; a full year had passed since then. Regardless of Bunker Hill, the British were incensed by the creation of the Continental Army, and passed the Prohibitory Act, which declared that all thirteen colonies (belonging to the Congress) were renegades, their decision to raise armies placing them "outside the protection of the king". All American shipping was now subject to seizure, not just that of Massachusetts, as were foreign vessels engaged in American trade. News of this Parliamentary thunderbolt first came to Robert Morris through one of his ships, accompanied by news that 26,000 troops had been raised for an invasion of American ports. The British position was that all thirteen colonies had gratuitously formed a government and an army, and needed to be punished for such treason. Pennsylvania was no exception; the offending Continental Congress had met there, and Benjamin Franklin had represented both Massachusetts and Pennsylvania before Parliament. Confirmation of that particular British attitude toward them greeted Pennsylvanians when British warships promptly appeared in May 1776, to patrol the mouth of Delaware. Three cruisers exploring up the river were attacked by American galleys. In response, the cruisers sailed directly at Philadelphia until they were finally beaten back by citizen flotillas, supervised by Robert Morris and the Committee on Safety. Morris wrote to Silas Deane in Paris that war was probably inevitable. Far less tentatively, the British felt it had already been in progress for a year.

The British Ministry had probably been unreasonably hostile, but they were not unanimous and they were not fools. In response to colonial unrest up until these almost irretrievable events, the British were concentrating on depriving the colonists of arms and gunpowder, mostly avoiding direct violence; it seemed an effective strategy. During the Boston Tea Party, for example, British warships in Boston harbor merely stood by and watched the fun. Although gunpowder was a simple chemical, comparatively easy to make, it was less likely to blow up in your face if finely ground and milled in a major factory; for a real Colonial war it had to be imported. The British strategy had been: Take away their weapons, and they will capitulate. Unfortunately, that was not the response at all, since even loyal colonists felt they needed good gunpowder for hunting and self-protection. Gunpowder blockades and confiscations were going to be bitterly resented. Nevertheless, British patience with the colonists was probably only irretrievably exhausted in June 1775, when the Continental Congress formed its own army and Washington marched them to Boston. If Pennsylvania became convinced of that inevitability, the war was certainly on. After the naval battles right here on Delaware, what really became hard to believe was that -- only a week earlier -- Pennsylvania's moderate voters had soundly defeated the revolutionary radicals in an Assembly election.

Pennsylvania had indeed been far less eager to fight than Massachusetts and Virginia, but the more belligerent colonies felt they needed allies in order to prevail. In the Continental Congress Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against rebellion in the Spring of 1776; and in the May 1776 election where independence was the main issue, the Pennsylvania voters elected an Assembly 70% opposed to rebellion, including that eminent merchant Robert Morris. Some of the determined Massachusetts efforts to persuade the Mid-Atlantic colonies bordered on subversion, but Pennsylvania remained unmoved. Nevertheless, they could see a real danger of war and had approved Secret Committees to be prepared if it came. Robert Morris was ideal for covert activity and could be expected to keep the activity under control, along with Benjamin Franklin and several prominent merchants. Morris made no secret of his affection for England the country of his birth, or of his membership in the John Dickinson group which hoped economic pressures would suffice. When the Secret Committee chairman suddenly died of smallpox, Morris was then appointed a chairman. His personal integrity was widely respected; in several hotly contested elections, he was nominated by both the radicals and the conservatives.

It seems absolutely necessary to prepare a vigorous defense since every account we receive from England threatens nothing but destruction.

|

| Robert Morris: December 1775. |

The Secret Committee was charged with smuggling in some gunpowder, just in case. Several of the members agreed to ship arms and gunpowder in their own ships; there was no one else to do it. The decision to engage in treasonous gunrunning was greatly assisted by the unexpected appearance of two Frenchmen with aristocratic accents in a boat loaded with gunpowder, who proposed themselves as French counterparties in a major gunpowder and weapons smuggling network which did actually materialize. Just who sent them has never been made entirely clear, but later events make the playwright Beaumarchais a reasonable guess, acting as a secret agent of the French King. Beaumarchais the famous playwright had been caught in a police trap, and forced to act as a government spy; just whose agent he was is a little murky. The American merchants on the Secret Committee knew gun running was expensive for them; they all expected to be paid for dangerous work, so it was also profitable. And treasonous. If caught, there was every possibility of being hanged. Initially, the Americans all imagined the Frenchmen were simply in it for the money, and that is possible. Surprisingly, no one seems even to have speculated they were agents of the French government on a mission to stir up trouble against the English. Spies had surely informed the French King of approaching war, at least six months before the Americans knew of it. Since these two foreign shippers (giving their names as Pierre Penet and Emmanuel de Pliarne, and surely sent to spy) demanded to be paid in hard currency, Morris did send one ship with hard money to pay for munitions to be carried in its hold on the return voyage. But he soon devised safer payment approaches.

For my part I abhor the name & the idea of a rebel, I neither want or wish a change of King or Constitution & do not conceive myself to act against either when I join America in defense of Constitutional Liberty.

|

| Robert Morris: December 1775 |

Since he had agents and offices in most major foreign ports, Morris could arrange for the money to arrive independently of the cargo ships. Or better yet, send ordinary commodities on the outward journey and make a private profit on that, returning with munitions paid for by the "remittances" -- revenue from the other cargo. Money was also sent on other circuitous journeys and through other channels, particularly the discounted debt system he had earlier perfected when the paper currency had been prohibited. There was thus less incriminating evidence on the ship, and even if the ship burned or everyone got hanged, the money was at least out of the hands of the enemy. Secrecy was, of course, essential, this activity could be called treasonous, and it was most assuredly smuggling. When neutral countries were found supporting gunrunning, that assistance might well be called an act of war, so all nations prohibited it. In spite of his earlier reluctance about independence, Morris could easily see that gunrunning by the privateers of a recognized nation might be better protected by the conventions of war than exactly the same activity conducted by, say, brigands, profiteers or pirates.

Gunrunning was always seriously dangerous; Morris soon lost four ships, one by a mutiny of secretly loyalist sailors, and two were captured by unscrupulous American privateers. There would be some protection from hanging for gun runners as authorized combatants of a recognized nation. In retrospect, we can now surmise that Franklin was committed to independence, and was probably nudging his friend on the Secret Committee. John Adams could barely contain himself, openly and repeatedly. Washington was already outside Boston leading an army. The commitment had many levels.

In July 1776 Morris was called on to vote in Congress for the independence he always said he opposed. Caesar Rodney rode in from Delaware to deliver his state for Independence; now, Pennsylvania alone stood in the way. When the moment came, on the advice of Franklin, Robert Morris, and John Dickinson left the room to allow other Pennsylvania delegates to constitute a Pennsylvania majority, casting the state's vote for the war. Commitment to the war had many variants, even after the war began.

Two Hotheads May Have Destroyed an Empire

|

| King George III |

Combatants in a war often personalize the enemy in a single person. In 1776 the American colonists blamed it all on King George III. The British might have picked Sam Adams or Thomas Paine. Things are of course always vastly complicated in the affairs of great nations. Economics and national power are strong forces, like our culture, religion, and the accidents of geography and history. But when matters teeter on the edge of a cliff, insignificant pests can occasionally start an avalanche.

|

| Charles Townshend |

Consider first Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of England's exchequer in 1768. Townshend didn't particularly want the job, hoping instead for the Admiralty. None of the political power brokers particularly wanted to give him the job, but ultimately regarded it as the place he could do the least harm. He might have had no less an advisor than Adam Smith, who was the tutor of his son, but Smith's letters to him are so servile that it seems unlikely he would urge free trade to such a headstrong merchantilist employer. It is intriguing to speculate this strange association might have sharpened Smith's opinions in the Wealth of Nations which first appeared in 1776./p>

|

| William Bradford |

Townshend had been a problem all his life. His mother was brilliant, and notoriously promiscuous. He and his father exchanged 2000-word letters explaining to each other how the other was completely wrong. Charles was witty, eloquent and charming when he wanted to be, and he married an enormously wealthy woman. After that, his family had no hold on him, and they rarely spoke to each other. The same charm and arrogance can be perversely effective in politics, so other politicians often just had to put up with him. But as politicians do, they roasted him in their letters and private conversations. His political opponent, Edmund Burke, was perhaps a most gentle critic when he observed, "His actions... seem never to have been influenced by his most wonderful abilities." Opponents, of course, welcome deficiencies in their enemies, while exasperated political allies can be the most scathing about team members who injure the party with misbehavior. Adam Smith referred to his employer as someone "who passes for the cleverest fellow in England." Chase Price described him as "utterly unhinged". Horace Walpole: "nothing is luminous compared with Charles Townshend: he drops down dead in a fit, has a resurrection, thunders in the Capitol, confounds the Treasury bench, laughs at his own party, is laid up the next day, and overwhelms the Duchess [of Argyll, his mother-in-law] and the good women that go to nurse him!" The final assessment of his biographer Sir Lewis Namier was "...illustrations of Charles Townshend's character can be picked out anywhere during his adult life. He did not change or mellow; nor did he learn by experience; there was something ageless about him; never young, he remained immature to the end."

What matters for contemporary American readers is Townshend's 14-year grievance against American legislatures which seem to have originated when he discovered the New York Legislature in 1754 up to its old tricks of refusing to provide funds for Royal initiatives it did not like. At the time, he was in his first public office, the Board of Trade and Plantations, and had written some highly arrogant orders to New York, making many high-handed and disdainful public asides to his friends, including his wish to have the Assembly cut out of appropriations except for token approval of them. He was young, so his wiser party colleagues simply deflected him. But by 1767 he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, a brilliant speaker, and no doubt had collected many political chits to be cashed in. The Townshend Taxes were enacted, his underlying personal grievances were well known, the colonial assemblies could see it meant big trouble.

Although almost no one could match Townshend for bizarre behavior, in Philadelphia at Front and Market Streets, there was another difficult personality, named William Bradford. As a printer and newspaper publisher, Bradford must have been a person of some note in a town of thirty thousand, but it is difficult to find a portrayal of him, and notes about his personal life are comparatively skimpy. We do know that he was a member of a family of newspaper printers, including grandfather, uncle, and son, all of whom had experienced official prosecution for defiance of government. His grandfather, also named William Bradford, is said to have had Quaker affiliation, but it is not particularly prominent in accounts of him, while almost no mention of Quaker affiliation is made of the rest of the family. Grandfather William had a notable apprentice named John Peter Zenger, who was prosecuted for libel against the Royal Governor of New York, defended in a famous trial by the Philadelphia Lawyer Andrew Hamilton, who established the principle that the truth is not a libel. We can rather safely presume that the younger William Bradford had grown up in an environment of hostility to authority, aggravated but not necessarily caused by some rather plain persecutions by authority. It may even have been specific hostility to British authority, since in 1754 young Bradford began publication of a specifically anti-British paper, The Weekly Advertiser. It is interesting to note that its principle competitor was a pro-British paper printed by Ben Franklin. Somewhere along the line, Bradford became head of the Sons of Liberty, clearly marking him as strongly anti-British, probably well before the Townshend Acts.

Bradford established the London Coffee House at Front and Market Streets in Philadelphia. That might seem a strange sideline for a printer, until you reflect that the location was right beside the waterfront, especially the Arch Street warf. Newspapers in those days almost never had professional reporters, depending for their content on gossip from visiting ships. A coffee shop near the waterfront would be an excellent place to hear the maritime news of the world, and possibly hear it sooner than competitors. The London Coffee House provided a place for bargaining and trade; the Maritime Exchange got its start there. It may or may not be significant that a main activity of the Exchange was to buy and sell slaves. It is sure that the Navigation Acts and the Townshend taxes on various imports were a central topic of angry discussion in a waterfront Coffee House from 1768 to 1776. Thus it is possible that Bradford was caught up in the excited opinions of his customers, but plenty of evidence of anti-British sentiment exists in his background to suppose he nursed a long-standing prejudice against the British government. Our most authoritative account of the events appeared in the Pennsylvania Packet of January 3, 1774, but the beginnings of the story were better related in the Pennsylvania Mercury of October 1, 1791, shortly after Bradford's death.

"After the Tax on Tea imported into America was reduced to 3d. per pound by the British Parliament, there appeared to be a general disposition in the colonies to pay it. In this critical situation of the Liberties of America, Mr. Bradford stopped two or three citizens of Philadelphia, who happened to be walking by the door of his house on Front-street, and stated to them the danger to which our country was exposed, by receiving, and paying the tax on, the tea. Many difficulties stared the gentlemen, to whom he spoke, in the face...; and it was particularly mentioned that the citizens of Philadelphia were tired out with town and committee meetings, and that it would be impossible to collect a sufficient number of them together, to make an opposition to the tea respectable and formidable. 'Leave that business to me(said Mr. Bradford),--I'll collect a town meeting for you--Prepare some resolves;--and,--they shall be executed.' The next evening he collected a few of such citizens who were heartily opposed to the usurpations of the British Parliament, who drew up some spirited resolutions to reject the dutied tea, and to send back the tea ship. These resolutions were adopted the Saturday following (October 16, 1773), by a large and respectable town meeting at which the late Dr. Thomas Cadwalader (a decided Whig) presided. The same resolutions were immediately afterwards (November 5, 1773) adopted, nearly word for word, by a town meeting in Boston, where a disposition to receive the tea had become general, from an idea that opposition to it would not be seconded or supported by any of the other colonies. The events (December 16, 1773) which followed the adoption of these resolutions in the town of Boston are well known. However great the merit and sufferings of that town were in the beginning of the war, it is a singular fact, and well worthy of record in the history of the events which produced the American Revolution, the First act in that great business originated in Philadelphia, and that the First scene in it originated with Mr. William Bradford."

Written within a few days of the events, the January 3, 1774 Pennsylvania Packet is more detailed. In particular, the grievance is stated to be "...the pernicious project of the East India Company, in sending Tea to America, while it remains subject to a duty, and the Americans at the same time confined by the strongest prohibitory laws to import it only from Great Britain." While it is not easy to find a quotation capsulizing the British response, it would be something to the effect that the Tea Act was in fact a face-saving gesture which reduced the price of tea for the colonists, and was received as such by most of them, until smugglers of Dutch tea now faced the same surplus of unsold tea which had nearly bankrupted the East India Company after the colonies resorted to non-importation. Both arguments contain a certain amount of spin, but side-by-side, they contained sufficient reasonableness to permit peaceful resolution. To go on with the details:

"Upon the first advice of this measure, a general dissatisfaction was expressed, that, at a time when we were struggling with this oppressive act, and an agreement subsisting not to import Tea while subject to the duty, our subjects in England should form a measure so directly tending to enforce the act and again embroil us with our parent state. When it was also considered that the proposed mode of disposing of the Tea tended to a monopoly, ever odious in a free country, a universal disapprobation showed itself throughout the city. A public meeting of the inhabitants was held at the State-House on the [16]th October, at which great numbers attended, and the sense of the city was expressed in [the following] eight resolves:"

which we will divide into three sections for commentary. Resolves 1,2, and 5 can be said to be a protest against the Tea Act. While the language is a little high-flown, such a protest would be considered a normal exercise of free speech:

"1. That the disposal of their own property is the inherent right of freemen;that there can be no property in that which another man can, of right, take from us without our consent: that the claim of Parliament to tax America is, in other words, a claim of right to levy contributions on us at pleasure. "2. That the duty imposed by Parliament upon Tea landed in America is a tax on the Americans, or levying contributions upon them without their consent. "5. That the resolution lately enered into by the East India Company to send out their Tea to America , subject the payment of duties on its being landed here, is an open attempt to inforce this ministerial plan, and a violent attack upon the liberties of America. "

Resolutions 3. and 4. are accusations of a deeper plot. The colonists do not want to be taxed by the British Government directly, but prefer to tax themselves so that final payment to colonial officials must pass through colonial control. Unspoken, of course, is the creation of an ability to thwart implementation of unwelcome directives from London:

"3. That the express purpose for which the tax is levyed on the Americans, namely for the support of government, administration of justice, and defence of his Majesty's dominions in America, has a direct tendency to render Assemblies useless, and to introduce arbitrary government and slavery. "4. That a virtuous and steady opposition to this ministerial plan of governing America is absolutely necessary to preserve even the shadow of liberty, and is a duty which every freeman in America owes to his country, to himself, and to his posterity".

Finally, in the tradition of the writing of resolutions, come the so-called Resolves, the solution to the problem which you wish your audience to agree to. These concrete actions are found in resolutions 6, 7, and 8. The British could be expected to be offended, since the Resolves do not acknowledge the right of Parliament to impose the tax, or humbly petition that they reconsider. Rather, they assume the role of sovereign government themselves, effectively declaring the colonies would punish anyone who obeyed the Law, would coerce those who are charged by Parliament to implement the Law, and would cause those appointed by Parliament to do this work, to resign or else the peace would be disturbed by colonial enforcement of these 'suggestions':

"6. That it is the duty of every American to oppose this attempt. "7. That whoever shall, directly or indirectly, countenance this attempt, or in any wise aid or abet in the unloading,receiving and vending the Tea sent, or to be sent out by the East India Company, while it remains subject to the payment of the duty here, is an enemy to his country. "8. That a Committee be immediately chosen to wait on these gentlemen, who, it is reported , are appointed by the East India Company to receive and sell said Tea, and request them, from a regard to their own character, and the peace and good order of the city and province, immediately to resign their appointment."

The thinly-veiled threats contained in these resolutions against anyone who disagreed were soon made more explicit when the tea ship actually arrived at the mouth of the Delaware around December 23, 1773, by public posters to the Delaware River pilots and Captain Ayers of the incoming Tea ship, signed by THE COMMITTEE FOR TARRING AND FEATHERING. Cards were printed up for the public to distribute around the premises of James and Drinker, telling them to resign as sales agents for the Tea by writing a note, to be delivered to the London Coffee House -- William Bradford's place of business. A few shouts and the waving of a few torches would have been sufficient to indicate that the alternative was arson.

A month elapsed between the proclamation of the Philadelphia resolutions and the actual arrival of Captain Ayers in our harbor. Another tea ship had arrived at Boston in the meantime on December 16,1773. The Boston citizens had dressed themselves as Indians, and dumped the Boston Tea consignment into the harbor, proclaiming the same eight Philadelphia-written resolutions. But in Philadelphia, violence proved unnecessary. James and Drinker resigned their appointments as sales agents, the pilots were ready enough to impede passage, and Captain Ayers on December 27, 1773 meekly sailed his cargo of Tea back where it came from.

Declaration of Independence: Jefferson's Response to Prohibitory Act

George III seems to have been told that actions speak louder than words, and the Prohibitory Act was not meant to demonstrate a need to conciliate. Jefferson's position was about the same as a young press agent for Congress. He went on and on about why the Colonists were the offended party and were going to put up a fight. It seems very doubtful the King paid any attention to what Jefferson said at such great length.

5 Blogs

Obamacare's Constitutionality

Obamacare's constitutionality was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in late March, 2012.

Obamacare's constitutionality was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in late March, 2012.

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

There were about 30,000 residents, just a small town, but it was the second largest city in the English-speaking world. Aside from wagons, there were thirty wheeled vehicles. But this is the town where decisions were made.

There were about 30,000 residents, just a small town, but it was the second largest city in the English-speaking world. Aside from wagons, there were thirty wheeled vehicles. But this is the town where decisions were made.

Pennsylvania: Browbeaten Into Joining a War

America declared Independence on July 4, 1776, but England had decided a year earlier to suppress the rebellion by overwhelming force and announced it six months later. France was then smuggling in gunpowder and guns. But Pacifist Pennsylvania held out until there was a British naval attack in the Delaware River, in May 1776, and a huge army had arrived at New Brunswick in June. The British wanted to confront us with a choice of surrender or subjugation. We picked the third choice the British never considered, to resist until they treated us better.

America declared Independence on July 4, 1776, but England had decided a year earlier to suppress the rebellion by overwhelming force and announced it six months later. France was then smuggling in gunpowder and guns. But Pacifist Pennsylvania held out until there was a British naval attack in the Delaware River, in May 1776, and a huge army had arrived at New Brunswick in June. The British wanted to confront us with a choice of surrender or subjugation. We picked the third choice the British never considered, to resist until they treated us better.

Two Hotheads May Have Destroyed an Empire

Charles Townshend and William Bradford were separated by an ocean, and surely never met. But if any two people can be said to have deliberately provoked the American Revolution, these two must be considered.

Charles Townshend and William Bradford were separated by an ocean, and surely never met. But if any two people can be said to have deliberately provoked the American Revolution, these two must be considered.

Declaration of Independence: Jefferson's Response to Prohibitory Act

Jefferson's Declaration was a long and flowery response to a terse Monarch's notice that He was in charge. That is, the King brushed aside the attempt to separate him from Parliament, and mostly just replied to colonial effrontery with overwhelming force. The colonials were right to suppose Admiral Howe intended to burn all thirteen colonies to the ground.

Jefferson's Declaration was a long and flowery response to a terse Monarch's notice that He was in charge. That is, the King brushed aside the attempt to separate him from Parliament, and mostly just replied to colonial effrontery with overwhelming force. The colonials were right to suppose Admiral Howe intended to burn all thirteen colonies to the ground.