4 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

Fanny Kemble

Fanny Kemble was more than the toast of the town, she was the most glamorous woman in the English speaking world. But far beyond that, she was a famous author, Shakespearean scholar, and had a major influence on the Civil War.

Fanny Kemble

|

| Fanny Kemble (Sully) |

Frances Anne Kemble, universally known as Fanny, was just about the most magnificent Philadelphia woman of the Nineteenth Century. She spent much of her time abroad and others claimed her, but she was ours. Coming from a famous English theater family, the niece of Mrs. Siddons and the daughter of the founder of Covent Gardens, she quickly rescued the failing family fortunes by becoming the most striking Shakespearean ingenue of the time. It took very little time for her to know Lord Byron, Thackeray, and various other luminaries of the literary and artistic world of Europe, along with Queen Victoria. One might as well say she knew everybody unless one made the point that everyone knew her.

|

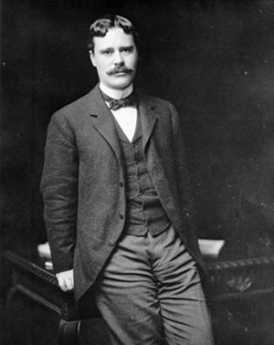

| Pierce Butler |

On a theatrical grand tour of America she met and married the Philadelphian Pierce Butler, one of the richest bachelors in the nation, heir to huge estates in Georgia. She had plenty of other choices, including the most dashing and romantic devil of the century, Trelawny. That glamorous friend of Byron's had been the one to drag Percy Shelley's body from the ocean, and was surely the greatest heartthrob of the century. Toward the end of her life, Fanny demonstrated the range of her appeal by totally subjugating the intellectual novelist Henry James, who was 34 years younger than she was. Her portraits by Sully now hang in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and in the Rosenbach Museum. Although Sully was said to have glamorized her a bit, her movie star qualities are evident. But appearance alone could not have mesmerized Henry James, known in literary circles as The Master. She was evidently one of those powerfully self-assured personalities encountered from time to time, who dominates every conversation, fills every room she enters, inspiring admiration rather than jealousy. As a youth, she was enchanting, as a mature woman, magnificent. Henry James described her as having "an incomparable abundance of being."

But this was not just another Cleopatra. Fanny Kemble had two personal achievements of enduring note. Because of health limitations, she went beyond being a Shakespearean actress to inventing a style of a public reading of Shakespeare, taking all the parts herself. She and Dr. Samuel Johnson were the two successive forces transforming Shakespeare's reputation from the quaint playwright of the past into the permanent towering figure of the English language.

Her other achievement destroyed her private life. As the wife of the owner of a thousand slaves, she led the attack on slavery before the Civil War. During the War, her passionate defense of emancipation was the main factor in persuading the British Government to refuse badly needed loans to the Confederacy. However, the publication of her journals was the last straw in a tumultuous marriage, and Pierce Butler divorced her, taking custody of their daughters, exiling her to England. Southern plantation owners were always short of cash, and realistically one has to acknowledge the strain of demanding to emancipate a thousand slaves, each one worth a thousand dollars. In one of the supreme ironies of a tragic situation, the forced sale of the slaves compelled the Butlers to liquidate an asset just before it was going to be destroyed by wartime events. Butler died in 1863, but she had done him a financial favor.

Fanny's daughter married Dr. Caspar Wistar, of Grumblethorpe and the grounds of present LaSalle College. Her grandson was Owen Wister, the college roommate of Teddy Roosevelt, later the author of The Virginian. Famous for the phrase "If you say that to me, smile", Owen Wister and his roommate created the fable of the romantic cowboy which still dominates movies and fiction, and, from time to time, the Presidency of the United States.

Fanny Kemble Takes the Train South, in 1838

The "Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839" raised strong feelings against slavery, particularly in Frances Anne Kemble's native England. At the outset of her book, Fanny Kemble describes what it was like to travel on American railroads in 1838.

On Friday morning December 21, 1838, we started from Philadelphia, by railroad, for Baltimore. It is a curious fact enough, that half the routes that are traveled in America are either temporary or unfinished -- one reason, among several, for the multitudinous accidents which befall wayfarers. At the very outset of our journey, and within scarce a mile of Philadelphia, we crossed the Schuylkill, over a bridge, one of the principal piers of which is yet incomplete, and the whole building (a covered wooden one, of handsome dimensions) filled with workmen, yet occupied about its construction. But the Americans are impetuous in the way of improvement and have all the impatience of children about the trying of a new thing, often greatly retarding their own progress by hurrying unduly the completion of their works, or using them in a perilous state of incompleteness. Our road lay for a considerable length of time through flat low meadows that skirt the Delaware, which at this season of the year, presented a most dreary aspect. We passed through Wilmington (Delaware) and crossed a small stream called the Brandywine, the scenery along the banks of which is very beautiful. For its historical associations, I refer you to the life of Washington. I cannot say that the aspect of Wilmington, as viewed from the railroad cars, presented any very exquisite points of beauty....

And first, I cannot but think that it would be infinitely more consonant with comfort, convenience, and common sense, if persons obliged to travel during the intense cold of an American winter in the Northern states, were to clothe themselves according to the exigencies of the weather, and so do away with the present deleterious custom of warming close and crowded carriages with sheet iron stoves, heated with anthracite coal. No words can describe the foulness of the atmosphere...Of course, nobody can well sit immediately in the opening of a window when the thermometer is twelve degrees below zero yet this, or suffocation in foul air is the only alternative...

We pursued our way from Wilmington to Havre de Grace on the railroad, and crossed one or two insets from the Chesapeake, of considerable width, upon bridges of a most perilous construction, and which, indeed, have given way once or twice in various parts already. They consist merely of wooden piles driven into the river, across which the iron rails are laid, only just raising the train above the level of the water. To traverse with an immense train, at full steam-speed, one of these creeks, nearly a mile in width, is far from agreeable...At Havre de Grace we crossed the Susquehanna in a steamboat, which cut its way through the ice an inch in thickness with marvelous ease and swiftness and landed us on the other side, where we again entered the railroad carriages to pursue our road.

Harvard Progressives in Philadelphia

|

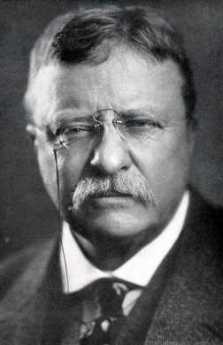

| Theodore Roosevelt |

The Progressive movement of the early 20th century is most concisely viewed as a futile social reaction to the vast changes in America caused by urbanization and industrialization after the Civil War. The transcontinental railroad threatened to destroy the wild, wild West, but the enduring environmental movement had overtones of even greater hostility toward industrialization, the cause of it all. In this sense, it joined forces with socialist and labor reform movements, in hating the newly rich, the spoilers, the Robber Barons. It briefly shared sympathies with anti-immigrant groups, while simultaneously expressing great sympathy with the decisions of the people, as opposed to corrupt politicians. There was a strong Calvinist streak in Progressivism, linked back to New England and Harvard its intellectual center. Regardless of any other contradiction, it reflected the viewpoint of Theodore Roosevelt. Teddy Roosevelt, "that damned cowboy" in the view of conservatives, did not invent the ideas of Progressivism, but he surely personified them, illustrated them in action. This confused turmoil of resentments was knocked off the front pages by a real threat to European civilization, the First World War. A terrifyingly well organized German war machine took the place of Robber Barons as a symbol of what was wrong with the world. The crash of 1929 and its ensuing long depression finally put an end to older controversies; it pushed the "reset" button.

|

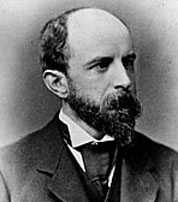

| Henry Brooks Adams |

To understand the position of Philadelphia's upper crust during the Progressive era, four or five names need to be fleshed out. Owen Wister and J. William White would be important Philadelphia links to the Bostonians Henry Adams and Henry James. All of them were leading literary figures, and all of them were close friends of Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt, it might be recalled, was the author of thirty-four books. This little group of literary giants were members of the leading families of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia; what they said, mattered. Although today Owen Wister is mainly known as the author of The Virginian, the first of the cowboy stories of the Wild West, he was, in fact, an observer of the social climates of not only the West, but the deep South (Lady Baltimore ), and the East Coast ( Romney). Some idea of his political leanings can be gleaned from his presidency of the Immigrant Restriction Society, and the authorship of an article called Shall We Let the Cuckoos Crowd Us From Our Nest . Wister has been called "the best born and bred of all modern writers", referring to his descent

| Posted by: Kasara | Nov 23, 2011 5:27 PM |

Dura lex, sed dura.

Solve vincla reis, profer lumen caecis.

Fide sed, cui vide.

Divide et impera.

Pecunia non olet.

O tempora, o mores!

Contra bonos mores.

| Posted by: Pro100nik | May 20, 2011 4:40 PM |

| Posted by: Pro100nik | May 18, 2011 9:17 PM |

3 Blogs

Fanny Kemble

Frances Anne Kemble had it all: fame, beauty, wealth, personal friendship with real royalty and literary royalty. Beyond that, she caused a major new understanding of Shakespeare and was a major force in the abolition of slavery. Philadelphia wasn't big enough to hold her; perhaps no town was.

Frances Anne Kemble had it all: fame, beauty, wealth, personal friendship with real royalty and literary royalty. Beyond that, she caused a major new understanding of Shakespeare and was a major force in the abolition of slavery. Philadelphia wasn't big enough to hold her; perhaps no town was.

Fanny Kemble Takes the Train South, in 1838

One of several important and influential books that Fanny wrote described her trip from the Philadelphia salons to the slave quarters of Georgia. It's well worth reading, even today.

One of several important and influential books that Fanny wrote described her trip from the Philadelphia salons to the slave quarters of Georgia. It's well worth reading, even today.

Harvard Progressives in Philadelphia

The Progressive movement of the early 20th century was a strange hodge-podge of political reformers, nostalgic aristocrats, would-be socialists, and anti-immigrant. The central figure was Theodore Roosevelt, traveling in strange company like Owen Wister, Robert M. LaFollette, Henry James, and Henry Adams. The Philadelphia link seems to have been through Harvard.

The Progressive movement of the early 20th century was a strange hodge-podge of political reformers, nostalgic aristocrats, would-be socialists, and anti-immigrant. The central figure was Theodore Roosevelt, traveling in strange company like Owen Wister, Robert M. LaFollette, Henry James, and Henry Adams. The Philadelphia link seems to have been through Harvard.