1 Volumes

G3 Favorites, Not Personal

Jes' Favorites

Newly Created Topic for Volume 97 (favorites)

I created this topic by cutting/pasting the blog numbers inadvertently entered into Volume 97

Abortion

The official position of the Pennsylvania Medical Society on the topic of abortion is, we have no position on abortion. I ought to know because I was the author of this position, proposed at a moment when the PA Medical House of Delegates was obviously going nowhere. After two hours of angry debate, we had to stop before we split into two warring medical societies. The Pennsylvania delegation to the AMA was then obliged to hold the same no-position on a national level. As I recall, our position was likewise greeted by the AMA House of Delegates with great relief, and word quickly circulated in the corridors that Pennsylvania had a position everyone could endorse for the good of the organization. For several years, this no-position position was widely referred to whenever the topic threatened to arise. It almost invariably stopped the discussion in its tracks, as it was intended to do. In going back over the minutes, it would appear the AMA never actually voted to adopt a no-position motion, a discovery that surprised but did not change the basic determination to let the rest of the nation settle this. We were going to stay out of it.

|

| Roe vs. Wade |

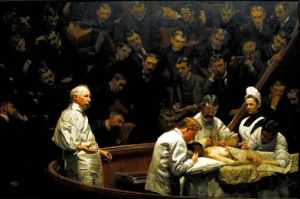

Because, one hundred forty years earlier, we started it. If you actually read Justice Blackmun's opinion for the majority in Roe v. Wade, as very few agitated proponents seem to have done, the original medical origin is clearly laid out. Blackmun had been a lawyer for the Mayo Clinic before his appointment to the Supreme Court, acquiring unusual medical resources and experiences for a lawyer. Now prepare for a logical leap, to the The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins masterpiece painting of Philadelphia's pre-eminent surgeon in a black frock coat, holding a dripping crimson scalpel in his bare hand, encapsulates the original situation. Note carefully that anesthesia is being given to the patient, but the surgeon is not wearing a cap, mask, gown, or rubber gloves.

|

| Gross Clinic |

In 1850 medical science had progressed into a forty-year time window when anesthesia made abortions painless, but Pasteur had still not identified bacteria, and Lister had not devised a way to cope with them. Abortions, common in ancient Greece but forbidden by Hippocrates, suddenly were widely demanded by 19th Century women in a situation when their judgment was vulnerable. Abortions were easy to do, all right, but women died like flies from the resulting infections, and the American Medical Association was distraught about it. The Oath of Hippocrates was brought forward to emphasize its prohibition of abortion, and the performance was made unethical for a member of the Association, sufficient cause to warrant expulsion. When that proved inadequate, the delegates agreed to go to their local state legislatures and seek legislation prohibiting the performance of abortion by anyone, member or non-member of the Association. These laws were quickly passed, and it was the Texas version which was overturned by Roe v. Wade as an unconstitutional denial of privacy. Roe was a pseudonym for the patient, and Wade was then Attorney General of Texas, the officer charged with enforcing Texas law. By 1900 abortions became both easy and safe for the mother, and by 1911 the AMA had reversed its position. The scientific surgical situation is well illustrated by a later famous painting about Philadelphia surgery by Thomas Eakins, the Agnew Clinic, in which the surgical team is portrayed in its modern costume of sterile gowns and rubber gloves. But it didn't matter since by that time various churches had hardened their doctrines. Religious leaders and their constituent politicians simply no longer cared what the medical profession thought about it. For at least the following century, ideological combatants were plainly only interested in whether physician opinion might advance one side or the other of their argument with useful official statements. Our real position, if anyone cares, is that we started out seeking protection for the safety of the mother, but the issue got twisted by others into disputes about the welfare of the unborn fetus.

|

| Agnew Clinic |

Since this is the case, there plainly may be a reason for state legislatures to reconsider the state laws they passed in the 19th Century, during that forty-year window of time when the scientific facts were in transition. But when a leap is made by the appointed referees of the federal government to overturn state laws, even about a basically medical issue, there has to be some legal reason to intervene; a medical reason somehow doesn't count. Justice Blackmun's discovery of an unnoticed right to "privacy" in the Constitution, where the word does not appear, is just too hard for us non-lawyers to deal with. Suppose we leave the fine points of the Bill of Rights to those constitutional lawyers. What's at stake here, among other things, of course, is whether the Federal Courts are justified in overturning well-intentioned state laws which had served well for at least fifty years -- simply out of impatience with the sluggishness and political timidness of state legislatures to revise obsolete laws. That's unbalancing the Constitution for a comparatively minor cause. Even major cause is something we have agreed to adjust in other ways, by amendment, not judicial opinion. And that's my opinion, having comparatively little to do with abortion.

Where Do Shad Go, When They Aren't Around Here?

|

| BAY OF FUNDY |

Some day, we're going to clean up our rivers, and then maybe the shad will come back. Since every female shad produces a couple hundred thousand eggs a season, when the shad come back, there could be a lot of them. We now know some things George Washington didn't know about shad. For example, they all go to the Bay of Fundy, once a year. All of them, whether they spawn in North Carolina, the Delaware, or the Connecticut River.

By tagging them, it was learned that shad swim at a depth of several hundred feet, apparently seeking a certain amount of darkness, which is in turn related to the growth of algae and plankton, their favorite food. So, when the surviving shad go back down a spawning river to the ocean, they head North in a huge counter-clockwise ocean rotation, adjusting their depth to the degree of darkness. Just about the time summering Philadelphians start packing for Bar Harbor, the shad also reach the Bay of Fundy, which is muddy and dark. Fundy is famous for its unusually high tides, so the turbulent water achieves the shad's desired degree of murkiness at about thirty feet instead of the normally deeper waters of the cyclic migration in the open ocean. People who know about these things say that just about every shad on the East Coast passes through the Bay of Fundy in late spring. In the fall, the fish turn around and start to go South again, maybe following the sun, maybe seeking a desired temperature, or both. Somehow or other, this pattern of migration helps them escape predator sharks and seals, as judged by that wholesome entertainment, the examination of stomach contents. Look out for sharks and seals in the open ocean, but striped bass are the big enemies of fingerlings in the spawning rivers. The Hudson River curiously has lots of striped bass lurking among the abandoned piers, and so does the Chesapeake. The Delaware also has a few stripers around the mouth of the Rancocas Creek; go ahead and fish 'em out.

All of this brings us to a suggestion for our tourist bureau. Shad don't eat much when they are on a spawning run, but they will strike at a lure. That is, you don't use worms, you do fly-casting. If we ever got anything approaching the old shad runs in the Spring, you could expect thousands and thousands of eager fly-casters to flock to the Delaware, filling up our marinas, hotels, restaurants, and cabarets. You wouldn't need to advertise a river teeming with eight-pound action-eager fish; the news would spread like magic. The best proof of this claim can be found on the only river on the East Coast which continues to have a classic shad run. The existence of this river was told to me as a sworn secret, but the invitation to try it was given with the assurance that "every single cast results in a strike".

And here's the zinger. Except for that one secret stream, the Delaware is the only major river on the East Coast that doesn't have a dam between the ocean and the spawning grounds. Once these fish have picked a river, they keep coming back to it, forsaking all others. The situation positively cries out for Federal assistance, and the lure-casting fishermen of America demand no less. Presidential elections have been won and lost on less important issues than this one. But just one dedicated congressman could do it, particularly if he sits on the Committee on Fisheries. Bring back our shad and get rewarded with lifetime incumbency that even Gerrymandering can't dislodge.

AFSC: American Friends Service Committee

Two things uniquely characterize the work of the Friends Service Committee (AFSC): it's often both dangerous and unpopular. That's not required for relief following Indonesian tidal waves perhaps, but the work that really needs someone to do is often both dangerous and controversial.

The Service Committee was founded in 1917, mostly by Rufus Jones and Henry Cadbury, as a way of helping conscientious objectors to World War I. The Mennonites, the Brethren, and the Quakers were opposed to all wars, not just that particular one, but two of those religions are of German ancestry, and lacked the same credibility of the English-origin Quakers in a war with English allies against the Huns, Boche, and Kaiser enemies. The early focus of the Committee was on the Field Service, or Ambulance Corps; which was plenty close to the action, and plenty dangerous. After the War, the defeated German population was starving, and the Quaker Herbert Hoover directed the relief effort with great credit to the Quaker name, and immense European gratitude.

After that, when German Jews were suffering persecution by the Hitler administration, the Quakers initially responded in a uniquely Quaker way. Rufus Jones and two other Quakers went to see Reinhard Heydrich, to tell him the world disapproved of his behavior. They fully realized they represented a pool of important world opinion, particularly within Germany, and it was time to speak truth to Power. The Germans left the room to confer, and the three Quakers bowed their heads in silent prayer. Apparently, the room was tape recorded, and when the German officials returned, they did promise some efforts to improve matters. As the situation for the Jews soon got much worse, many Quakers risked a great deal to shelter and rescue the persecuted exiles. Relief to the defeated German populace had to be repeated after that war, as well. Each effort built up more credibility to be able to switch sides for the next effort, and the sincerity has seldom been seriously questioned.

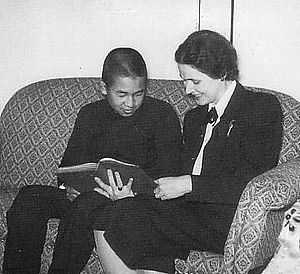

The Japanese were also our hated enemies in World War II, and once more a long history helped the relief effort. Nearly 100,000 American citizens of Japanese origin were interned on the West Coast as potential traitors in 1941, often under deplorable conditions. Clarence Pickett was a director of AFSC at the time, and his sister had spent years in Japan as a missionary, so his remonstrations with the American government were prompt and credible. One of the more active workers was Esther Rhoads, sister of the famous surgeon, who had spent time in Japan earlier. One of the ingenious efforts with the Nisei was to assist 4,000 of them to get into college and find them hostels and jobs while they were away at school. Many of these college students later became prominent in various ways, greatly assisting the post-war reconciliation between the two countries.

|

| Prince Akihito and Elizabeth Gray Vining |

Two Quaker ladies at the AFSC made a totally unique contribution when a request was received to provide a suitable tutor for the Crown Prince, now Emperor. He didn't convert to Christianity, but he later married a Christian, and you can be sure he got a plenty good dose of Quaker style and belief from Elizabeth Gray Vining. This tall, strikingly handsome Philadelphia woman had Bryn Mawr written all over her and turned heads whenever she entered a room. When she went back home, she was followed as a tutor for seven years by, guess who, Esther Rhoads who by then was the director of the Tokyo girls school. It remains to be seen, of course, what the final outcome of this deeply emotional situation will prove to have been. At the moment, the main sufferer seems to be the immensely talented American-educated woman who married the Emperor. But we will see; these are all powerful women in a very quiet way, unaccustomed to losing. One wishes the royal family all the best in their sometimes difficult position.

And then the Service Committee did its work in Vietnam, in Iraq, in Zimbabwe, and Somalia on the unpopular side, in every case. There are stories of venturing into war zones with hundred-dollar bills scotch-taped to their torso, where every fifty feet there was someone who would cut your throat for a dime. One worker in Laos entertained a group of us tourists with tales of living for weeks with nothing to eat but grasshoppers and cockroaches. Dangerous, unpopular, and uncomfortable. It sounds like a wonderful outlet for someone who is a perpetual rebel without a cause, but if you can find one of those at the Service Committee, you must have done a lot of looking.

The Service Committee, like the Quaker school system, is mostly run by non-Quaker staff. That means that neither of them exactly speaks for the religion itself. This little religious group of 12,000 members is stretched thin to provide a vastly greater world influence than its numbers imply. Hidden in the secrets of the group is an enduring ability to attract sincere non-member adherents to their work. And a quiet watchfulness to avoid losing control to any wandering rebels without a cause.

REFERENCES

| Window for the Crown Prince: Akihito of Japan, Elizabeth Gray Vining ISBN-13: 978-0804816045 | Amazon |

Battleship New Jersey: Home is the Sailor

|

Home is the sailor, wrote A. E. Housman, Home from the sea. In this case, the sailor is the Battleship New Jersey. The U.S.S. New Jersey rides at permanent anchor in the Delaware River, tied to the Camden side. You can visit the ship almost any afternoon, and with reservations can even throw a nice cocktail party on the fantail. It's an entertaining thing to do under almost any circumstances, but the trip is more enjoyable if you spend a little time learning about the ship's history. The volunteer guides, many of them still grizzled veterans of the ship's voyages, will be happy to fill in the details.

In the first place, the ship's final bloody battle was whether to moor the ship in the Philadelphia harbor, or New York harbor, when the U.S. Navy had got through using it. You can accomplish that and remain in the state of New Jersey either way, but there's a big social difference between North Jersey and South Jersey, so the negotiations did get a little ugly. Because of the way politics go in Jersey, it wouldn't be surprising if a few bridges and dams had to be built north of Trenton to reconcile the grievance, or possibly a couple of dozen patronage jobs with big salaries but no work requirement. The struggle surely isn't over. Battleships are expensive to maintain, even at parade rest; if you don't paint them, they rust. Current revenues from tourists and souvenirs do not cover the costs, so the matter keeps coming up in corridors of the capitol in Trenton.

Home is the sailor, home from sea:

Home is the hunter from the hill:

'Tis evening on the moorland free,

|

|

A. E. Housman

R.L.S. |

Battleship design gradually specialized into a transport vehicle for big cannon, ones that can shoot accurately for twenty miles while the platform bounces around on the ocean surface. Situated in turrets in the center of the vessel, they can shoot to both sides. That's also true of armored tanks in the cavalry, of course, with the history in the tank's case of the big guns migrating from the artillery to the cavalry, causing no end of a jurisdictional squabble between officers trained to be aggressive for their teams. Originally, the sort of battleship which John Paul Jones sailed was expected to attack and capture other vessels, shoot rifles down from the rigging, send boarders into the enemy ships with cutlasses in their teeth, and perform numerous other tasks. In time, the battleship got bigger and bigger so in order to blow up other battleships had to sacrifice everything else to sailing speed and size of cannon. Protection of the vessel was important, of course, but in the long run, if something had to be sacrificed for speed and gunpowder, it was self-protection. There's a strange principle at work, here. The longer the ship, the faster it can go. Almost all ocean speed records have been held by the gigantic ocean liners for that reason. If you apply the same idea to a battleship, the heavy armored protection gets necessarily bigger, and heavier as the ship gets longer, and ultimately slows the ship down. As a matter of fact, bigger and bigger engines also make the ship faster, until their weight begins to slow them down. Bigger engines require more fuel and carrying too much of that slows you down, too. Out of all this comes a need for a world empire, to provide fueling stations. Since the Germans didn't have an empire, they had to sacrifice armor for more fuel space and more speed, to compensate for which they had to build bigger guns but fewer of them. Although the British had more ships sunk, they won the battle of Jutland because more German ships were incapacitated. When you are a sailor on one of these ships, it's easy to see how you get interested in design issues which may affect your own future. An underlying principle was that you had to be faster than anything more powerful, and more powerful than anything faster.

The point here is that the New Jersey, as a member of the Iowa class of battleship, was arguably the absolutely best battleship in world history. At 33 knots, it wasn't quite the fastest, its guns weren't quite the biggest, its armor wasn't quite the thickest, but by multiplying the weight of the ship by the length of its guns and dividing by something else you get an index number for the biggest worst ship ever. The Yamamoto and the Bismarck were perhaps a little bigger, but the New Jersey was at least the fastest meanest un-sunk battleship. Air power and nuclear submarines put the battleship out of business so the New Jersey will hold the world battleship title for all time. Strange, when you see it from the Ben Franklin Bridge, it looks comparatively small, even though it could blow up Valley Forge without moving from anchor.

One story is told by Chuck Okamoto, a member of the Green Berets who was sent with a group of eight comrades into a Vietnamese army compound to "extract" an enemy officer for interrogation. When enemy flares lit up the area, it was clear they were facing thousands of agitated enemy soldiers, and Okamoto called for air support. He was told it would take thirty minutes; he replied he only had three minutes, and to his relief was told something could be arranged. Almost immediately the whole area just blew up, turned into a desert in sixty seconds. The guns of the New Jersey, twenty miles away, had picked off the target. The story got more than average attention because Okamoto's father was Lyndon Johnson's personal photographer, and Lyndon called up to congratulate.

A number of similar stories led to the idea that naval gunfire might have destroyed some bridges in Vietnam which cost the Air Force many lost planes vainly trying to bomb, but, as the stories go, the Air Force just wouldn't permit a naval infringement of its turf. This sort of second-guessing is sometimes put down to inter-service rivalry, but it seems more likely to be just another technology story of air power gradually supplanting naval artillery. Plenty of battleships were sunk by bombs and torpedo planes before the battleship just went away. If you sail the biggest, worst battleship in world history, naturally you regret its passing.

Tourists will forever be intrigued by the "all or nothing" construction of the New Jersey. Not only are the big guns surrounded by steel armor three feet thick, but the whole turret for five stories down into the hold is also similarly encased in a steel fortress. This design traces back to the battle of Jutland, where a number of battlecruisers were blown up because the ammunition was stored in areas of the hold not nearly so protected as the gun itself. Putting it all within a steel cocoon lessened that risk, and had the side benefit that when ammunition accidentally exploded, the damage was confined within the cocoon. It must have been pretty noisy inside the turret when it was hit, sort of like being inside the Liberty Bell when it clangs. But not so; stories have been told of turrets hit by 500-pound bombs which the occupants didn't even notice. The term "all or nothing" refers to the fact that the gun turrets are sort of passengers inside relatively unprotected steering and transportation balloon. In order to save weight, most of the armor protection is for the gun. That's a 16/50, by the way. Sixteen inches in diameter, and fifty times as long. With the weight distributed in this odd manner, the Iowa class of dreadnought was more likely to capsize than to sink. Accordingly, the interior of the hull is broken up into watertight compartments, serviced by an elaborate pumping system. Water could be pumped around to re-balance a flooded hull perforation, certainly a tricky problem under battle conditions.

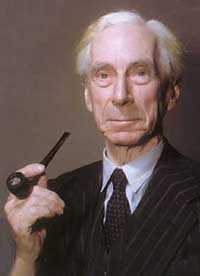

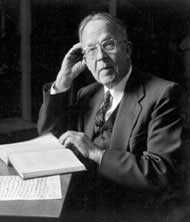

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

|

| Russell |

In 1940, the Barnes Foundation disturbed its Philadelphia's Main Line neighborhood in a way that had nothing to do with art. Dr. Barnes was still alive and running the place at that time so there can be no question about the testamentary intentions of the donor. He hired Bertrand Russell for a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Foundation, under highly lurid circumstances. By doing so, he put his thumb in the eye of religions generally but especially the Roman Catholic Church, into the eye of the Main Line neighborhood that prized its privacy, and into the eye of the judiciary, although the judiciary found a way to get back at him.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Under the circumstances, hiring anyone at all would have been socially defiant, but Barnes went out of his way to offer a position to a man who was already internationally famous for sticking his own thumb in everybody's eye.

Lord Bertrand Russell was the third Earl, the son of a Viscount and the grandson of a British prime minister. He had such a brilliant mathematical mind that no less an observer than Alfred North Whitehead regarded him as the smartest man he ever met. He burned up the academic track at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society at an early age. There was absolutely no one in the academic world who could look down on him, particularly no one in any American community college. His association with Haverford Quakers was established by marrying Alys Pearsall Smith, a rich thee-and-thou Quakeress then living in England, whose brother was the famous author Logan Pearsall Smith. Many early letters of Bertrand Russell contain instances of what the Quakers call "plain" speech.

If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

By the time of World War I, this odd mixture of Quaker pacifism and English aristocratic arrogance seems to have unhinged Russell from social moorings, and he began a lifelong career of defiance mixed with a rapier wit that made just about everybody his enemy. He went to jail for pacifism, got divorced three or four times, openly slept with the wives of famous people like T.S. Eliot, and proclaimed that monogamy was not a natural state for anybody. He wrote ninety books, and his denunciation of religion was sweeping. All religious ideas were, in his view, not only false but harmful. Accordingly, everybody in polite society kicked him out, and although he was entitled to a seat in the House of Lords, by 1939 he was nearly impoverished. In desperation, he went to (ugh) America to seek his fortune. He didn't last at the University of Chicago, and even California eased him out. Finally, he was reduced, if you can imagine, to accepting an offer to teach Philosophy at the City College of New York. That proved to be totally unacceptable to Bishop Manning, who led a public outcry against using public funds to support such a radical, known to have held long conversations with Lenin. When a CCNY student was induced to file suit along those lines, an especially hard-nosed judge overturned the College appointment, with the rather gratuitous declaration that Russell's appointment would establish a Chair of Indecency. At that point, Albert Barnes stepped in and offered Russell a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia's main line.

|

| Bertrand Russell in 1960s regalia. |

Bertrand Russell the bomb-thrower accepted the offer and came down to that quiet little lane where the neighbors object to the traffic coming to look at pictures. The five-year contract only lasted three years, when even Barnes got fed up, and summarily dismissed him. The circumstances have not been extensively documented, but they were sufficient to enable Russell to win a lawsuit for a redress of grievances. During that three year period on the Main Line, he had produced a book called History of Western Philosophy, which became a best seller and permanently relieved his financial difficulties, and was the basis for his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent the rest of his ninety-odd years leading demonstrations against the atom bomb, the Vietnam War, monogamy, religion and so on. There are those who regard Bertrand Russell as the role model for the whole Sixties generation, and, unfairly, the 2004 Democrat candidate for President. However, all that may be, his activity at the Barnes Foundation undoubtedly was a factor in the firm but the unspoken tradition of the Merion Township neighbors that they wanted to get that Art Gallery out of here.

Cecilia Beaux, Portraitist of the Grand Manner

|

| Cecilia Beaux |

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) was certainly the most famous woman portraitist of her time. She had the misfortune of being a contemporary of Mary Cassatt, who enjoyed the reputation of the finest woman Impressionist at a time when the Art world disdained traditional painting techniques in an Impressionist stampede. So, although these two temperamental artists might never have been chums, much of their famous rivalry was probably invented for them by art world politicians.

In time, the assessment will emerge that these two well-born Philadelphia ladies were each the world's female leaders of two competing schools of art. Comparisons of the two will also have to be filtered through the fact that Cassatt was a rebel who spent most of her life in Paris, while Beaux was a prominent faculty member of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for twenty years. Strikingly beautiful herself, she was gifted, elegant and fiercely ambitious. Meow.

|

Once Beaux had established a reputation as a portrait painter, she shrewdly began to select her subjects. She wanted famous men (Henry James, for example) and beautiful women subjects. She made the mistake of turning down her niece, Catherine Drinker Bowen, because she didn't have the right kind of cheekbones. She learned, of course, that it's unwise to tell a famous author she is ugly.

|

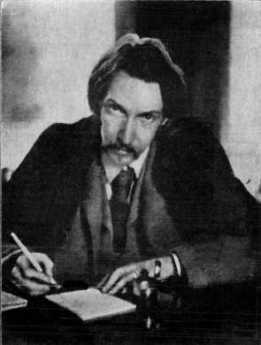

| Robert Louis Stevenson |

Cecilia Beaux's main competitor in the portrait game was John Singer Sargent, who was if anything a better painter but a stammering social dud. Sargent remained a life long bachelor, Beaux a spinster. Her mother had died in childbirth, and it seems likely that terror of pregnancy was an important part of her personality, during the pre-antibiotic era when such fear was fairly justified. As a young woman, she turned down proposals by the dozen, and in maturity, she had a succession of apparently platonic but intense relationships with handsome men twenty years her junior. During the late Victorian era, this sort of thing was not rare, although medical advances have apparently largely eliminated it. To return to her competition with Sargent, the personality differences probably account for his haunting portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, while Beaux is notable for arresting portraits of rich, famous and beautiful women, and an equal number of well-dressed, handsome men.

Washington Lurks in Bucks County, Waiting for Howe to Make a Move

|

| Moland House |

Although Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is staunchly Republican, it has been home to Broadway playwrights for decades; this handful of Democrats have long been referred to as lions in a den of Daniels. One of them really ought to make a comic play out of the two weeks in August 1777, when John Moland's house in Warwick Township was the headquarters of the Continental Army.

John Moland died in 1762, but his personality hovered over his house for many years. He was a lawyer, trained at the Inner Temple and thus one of the few lawyers in American who had gone to law school. He is best known today as the mentor for John Dickinson, the author of the Articles of Confederation. Our playwright might note that Dickinson played a strong role in the Declaration of Independence, but then refused to sign it. Moland, for his part, stipulated in his will that his wife would be the life tenant of his house, provided -- that she never speak to his eldest son.

Enter George Washington on horseback, dithering about the plans of the Howe brothers, accompanied by seven generals of fame, and twenty-six mounted bodyguards. Mrs. Moland made him sleep on the floor with the rest.

Enter a messenger; Lord Howe's fleet had been sighted off Patuxent, Maryland. Washington declared it was a feint, and Howe would soon turn around and join Burgoyne on the Hudson River. Washington had his usual bottle of Madeira with supper.

A court-martial was held for "Light Horse Harry" Lee, for cowardice. Lee was exonerated.

Kasimir Pulaski made himself known to the General, offering a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, which letters Franklin noted had been requested by Pulaski himself. As it turned out, Pulaski subsequently distinguished himself as the father of the American cavalry and was killed at the Battle of Savannah.

|

| Lafayette |

And then a 19 year-old French aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette, made an appearance. Unable to speak a word of English, he nevertheless made it clear that he expected to be made a Major General in spite of having zero battlefield experience. He presented a letter from Silas Deane, in spite of Washington having complained he was tired of Ambassadors in Paris sending a stream of unqualified fortune hunters to pester the fighting army. Deane did, however, manage to make it clear that the Marquis had two unusually strong military credentials. He was immensely rich, and he was a dancing partner, ahem, of Marie Antoinette.

In Mrs. Moland's parlor, Washington sat down with Lafayette to tap-dance around his new diplomatic problem. It was clear America needed France as an ally, and particularly needed money to buy supplies. But it was also clearly impossible to take a regiment away from some American general, a veteran of real fighting, and give that regiment to a Frenchman who could not speak English and who admitted he had no military experience. Fumbling around, Washington offered him the title of Major General, but without any soldiers under his command, at least until later when his English improved. To sweeten it a little, Washington seems to have said something to the effect that Lafayette should think of Washington as talking to him as if he were his father. There, that should do it.

It seems just barely possible that Lafayette misunderstood the words. At any rate, he promptly wrote everybody he knew -- and he knew lots of important people -- that he was the adopted son of George Washington.

Well, Broadway, you take it from there. At about that moment, another messenger arrived, announcing Lord Howe at this moment was unloading troops at Elkton, Maryland. General Howe might have been able to present his credentials to Moland House in person, except that his horses were nearly crippled from spending three weeks in the hold of a ship and needed time to recover. Heavy rains were coming.

(Exunt Omnes).

Suggested Stage Manager: Warren Williams

Eakins and Doctors

|

| The Gross Clinic |

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture.

Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition.

S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work.

In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

|

| Operating Amphitheater |

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing.

That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies.

The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer.

Fanny Kemble

|

| Fanny Kemble (Sully) |

Frances Anne Kemble, universally known as Fanny, was just about the most magnificent Philadelphia woman of the Nineteenth Century. She spent much of her time abroad and others claimed her, but she was ours. Coming from a famous English theater family, the niece of Mrs. Siddons and the daughter of the founder of Covent Gardens, she quickly rescued the failing family fortunes by becoming the most striking Shakespearean ingenue of the time. It took very little time for her to know Lord Byron, Thackeray, and various other luminaries of the literary and artistic world of Europe, along with Queen Victoria. One might as well say she knew everybody unless one made the point that everyone knew her.

|

| Pierce Butler |

On a theatrical grand tour of America she met and married the Philadelphian Pierce Butler, one of the richest bachelors in the nation, heir to huge estates in Georgia. She had plenty of other choices, including the most dashing and romantic devil of the century, Trelawny. That glamorous friend of Byron's had been the one to drag Percy Shelley's body from the ocean, and was surely the greatest heartthrob of the century. Toward the end of her life, Fanny demonstrated the range of her appeal by totally subjugating the intellectual novelist Henry James, who was 34 years younger than she was. Her portraits by Sully now hang in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and in the Rosenbach Museum. Although Sully was said to have glamorized her a bit, her movie star qualities are evident. But appearance alone could not have mesmerized Henry James, known in literary circles as The Master. She was evidently one of those powerfully self-assured personalities encountered from time to time, who dominates every conversation, fills every room she enters, inspiring admiration rather than jealousy. As a youth, she was enchanting, as a mature woman, magnificent. Henry James described her as having "an incomparable abundance of being."

But this was not just another Cleopatra. Fanny Kemble had two personal achievements of enduring note. Because of health limitations, she went beyond being a Shakespearean actress to inventing a style of a public reading of Shakespeare, taking all the parts herself. She and Dr. Samuel Johnson were the two successive forces transforming Shakespeare's reputation from the quaint playwright of the past into the permanent towering figure of the English language.

Her other achievement destroyed her private life. As the wife of the owner of a thousand slaves, she led the attack on slavery before the Civil War. During the War, her passionate defense of emancipation was the main factor in persuading the British Government to refuse badly needed loans to the Confederacy. However, the publication of her journals was the last straw in a tumultuous marriage, and Pierce Butler divorced her, taking custody of their daughters, exiling her to England. Southern plantation owners were always short of cash, and realistically one has to acknowledge the strain of demanding to emancipate a thousand slaves, each one worth a thousand dollars. In one of the supreme ironies of a tragic situation, the forced sale of the slaves compelled the Butlers to liquidate an asset just before it was going to be destroyed by wartime events. Butler died in 1863, but she had done him a financial favor.

Fanny's daughter married Dr. Caspar Wistar, of Grumblethorpe and the grounds of present LaSalle College. Her grandson was Owen Wister, the college roommate of Teddy Roosevelt, later the author of The Virginian. Famous for the phrase "If you say that to me, smile", Owen Wister and his roommate created the fable of the romantic cowboy which still dominates movies and fiction, and, from time to time, the Presidency of the United States.

Helis the Whale

|

| Beluga Whale |

Helis the beluga whale, male, 12 feet long, said to be 30 years old in a species with a life expectancy of about 35, made an appearance in the upper Delaware River in the spring of 2005. A scar on his back was recognized as having been seen on the St. Lawrence River, where Beluga whales are more commonly observed. Needless to say, there was a local sensation, with crowds of whale-watchers along the banks of the river, sharing binoculars, and buying special whale cookies, t-shirts and the like from opportunistic vendors. Helis arrived April 14, 2005, in time to pay income taxes, go to Trenton, cruising Trenton to Burlington and back, eating shad. Experts saying he is happy as a clam, shad fishermen grumbling a little. Crowds of excited people tried to take snapshots of themselves with Helis in the background.

He stayed with us another week, going back and forth between Burlington and Trenton. Not many other events took place, so the newspapers had front-page stories by Beluga whale experts, sought out for fifteen minutes of fame. Will he come back? How big do Belugas get to be? Frantic calls by reporters obtained the information that Belugas like icy arctic waters, seldom travel alone or this far south. The suggestion was made that Helis may have been banished by the male whales he usually swims with, but others pointed out the unusually good shad run this year and conjectured Helis was an adventurous loner who had discovered a private river of goodies.

|

| Cape May NJ |

We were informed that lots of whales are sighted off Cape May every year; there's a rather large whale sight-seeing industry. Mammals don't breathe the Delaware pollution, but like other mammalian swimmers, they swallow some. So here's a sign that river pollution maybe can't be too bad.

The French Canadians call him "ee-lus" but don't expect that to catch on around here. What's helis mean, anyway? This seems to be the most southern sighting of a Beluga. Reminds us that Kingston New York, a hundred miles up the Hudson, used to be a big whaling port. that Ahab of Melville's Moby Dick was a Quaker, Nantucket variety. Cape May Quakers are related to them more than to Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. After all, Philadelphians are whale-lovers.

Unless someone harpoons Helis, we are all hoping he will bring back lots of his friends next year. Even the shad fishermen recognize that if the whales are searching for shad, there have to be a lot of shad to be attractive. And the whale-memento industry will surely be ready for them.

Henry Cadbury Dresses Up for the King

|

| Henry Cadbury |

There are a few old Quaker Clothes in the attics of their descendants, and on suitable occasions, an old broad-brimmed hat or two will appear at a Quaker gathering, for amusement. Quakers gave up the old style of "plain dress" when it became generally agreed that such eccentric dress was not plain at all but rather drew attention to itself. On the other hand, there is a distinctly unfashionable quality to almost everything Quakers do wear. When silk and nylon stockings were fashionable for women, Quaker women often wore black stockings. When it became the style for women to sport black stockings, Quaker women usually wore flesh-colored nylons. Among men, thin metal-trimmed spectacles displayed the same counter-fashionable tendency. Nowadays, these little quirks are often public signals among strangers, a way of wig-wagging "I notice you are a Quaker, so am I." And of course, unfashionable clothes are cheaper, and that's always a good thing.

And so it happened in 1947 that the Quakers were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, with information passed along that white tie and tails were the expected form of dress at the ceremony. Henry Cadbury was selected to receive the award on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, and you can be sure Henry Cadbury didn't own a set of tails. Henry was also very certain he wasn't going to go out and buy a set, just for a single wearing.

The AFSC collects used clothing, to distribute to the poor. Henry inquired whether there might be a set of white tie and tails to be found in the used-clothing bin, and luckily there was. It had been collected on behalf of the Budapest Symphony Orchestra when that impoverished but distinguished group of musicians was invited to give a concert in London. One of the monkey suits more, or less, fit Henry.

So, after investing in dry cleaning and pressing, Henry packed it up and went off to Oslo, to meet the King.

House that Love Built: Ronald McDonald of Philadelphia

Kim Hill had the misfortune to develop leukemia, but the great luck to have Fred Hill of the Philadelphia Eagles football team for a father. Driven by gratitude for the treatment at St. Christopher's Hospital for Children

|

| Audrey Evans |

Fred demanded to be told what he could do and was referred to Dr. Audrey Evans. This world-famous pediatric oncologist was well known for her philanthropic activities and had frequently expressed the need for a temporary residence for families of children needing protracted medical treatments. Young children have young parents, whose savings are soon exhausted by travel, hotel and other non-insured costs related to a seriously sick child. The Hills had just been through such an experience and grasped the problem immediately, adding to it the discomfort and loneliness of families in such a situation. Fred Hill quickly enlisted the enthusiastic support of the whole professional football organization, and Jim Murray the Eagles' general manager recruited Don Tuckerman from their advertising agency, who got to Ed Rensi, the regional manager of McDonald's. Together, they got the project financed and started with a seven-bed facility near Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

|

| Fred Hall |

In 25 years, the Philadelphia Ronald McDonald House has grown to a capacity of 44 families, in a century-old mansion at 39th and Chestnut Streets filled with Mercer tiles and the like. The operation uses eighteen volunteers at all times, runs two jitney buses, and is one huge teeming family home for people confronting a common issue, supporting each other through a wrenching emotional experience. Although it actually costs about $65 a day per family, the charge is $15 and over half of the clients cannot afford even that. Although an effort is made to have family cooking, the McDonald's restaurant chain supplies 20% of the budget along with generous help with exigencies and in-kind assistance with such things as clowns for the entertainment program, birthdays and the like. Although McDonalds's is probably the world's premier franchising corporation, every one of the 300 worldwide Ronald McDonald Houses is an independent local organization, run without a central headquarters or any sort of standards-setting and the like. Every one of the other 299 Houses got the idea from Philadelphia but proceeds in its own way. Philadelphia created it, but Philadelphia does not own the idea.

In this connection, it is probably worth reflecting on the history of this topic. When Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond started the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751 at Eighth and Spruce Streets, it was the custom to be diagnosed, treated, be born and to die in your own house. The unique perception behind the nation's first hospital was that poor people generally did not have home facilities that were adequate to support home care. In Franklin's own handwriting the purpose of the Pennsylvania Hospital was stated to be "for the sick poor, and if there is room, for those who can pay." It was understood that poor sick people needed a place to take care of them, not merely for their surgery and overwhelming illness,

<but for convalescence and rehabilitation as well. Two centuries later, in the first thrill of founding the Medicare and Medicaid programs, it was imagined that things would remain exactly the same, only paid for by the Government. But after four or five years, it became abundantly clear that it was far too expensive to use hospitals in that way. The very act of federally paying for the program undermined its volunteer spirit, raised its mandated standards, and made it financially unsustainable. And so, although the 1965 Amendments to the Social Security Act insisted, and still pretend, that no change was to be made to the delivery of care, the delivery of care simply had to be changed. Not only was domiciliary and custodial care to be excluded, but heroic efforts were to be made to reduce the length of stay in the hospital to what would once have been regarded as special intensive care. In effect, if a type of service could normally be handled at home by non-indigent people, it was to be prohibited for everybody. Since the cost of care in hospital has continued to escalate far in excess of the cost of living, it seems unlikely we will ever go back to the days of rest and in-hospital recuperation.

So, just as Dr. Bond recognized the problem and went to Ben Franklin to handle the philanthropy, Dr. Evans had the idea and Fred Hill made it work. Around the Ronald McDonald house, the idea is frequently heard expressed that every hospital needs such a place nearby, for people of all ages. Perhaps that is workable, but it offhand seems more likely that Retirement Villages, so-called CCRC, will be called on to supply this badly needed service, at least for senior citizens. And that what we now call hospitals will evolve into the scientific "focused factories" so popular in the minds at the Harvard Business School.

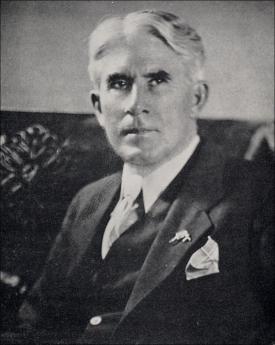

James A. Michener (1907-1997)

|

| James A. Michener |

James Michener seemed headed for a recognizably Quaker life until show business rearranged his moorings. He was raised as a foundling by Mabel Michener of Doylestown, Pennsylvania, under circumstances that were very plain and poor. Many of his biographers have referred to his boyhood poverty as a defining influence, but they seem to have very little familiarity with Quakers. When the time came, this obviously very bright lad was offered a full scholarship to Swarthmore College, graduated summa cum laude, went on to teach at the George School and Hill Schools after fellowships at the British Museum. And then World War II came along, where he was almost but not exactly a conscientious objector; he enlisted in the Navy with the understanding he would not fight.

While in the Pacific, he had unusual opportunities to see the War from different angles, and wrote little short stories about it. Putting them together, he came back after the War with Tales of the South Pacific. Much of the emphasis was on racial relationships, the Naval Nurse who married a French planter, the upper-class Lieutenant (shades of the Hill School) who had a hopeless affair with a local native girl that was engineered by her ambitious mother, as central characters. Michener himself married a Japanese American, Mari Yoriko Sabusawa, whose family had been interned during the War. There are distinctly Quaker themes running through this story.

And then his book won a Pulitzer Prize, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein made it into a Broadway musical hit, then a movie emerged. The simple Quaker life was then struck by the Tsunami of Broadway, Hollywood, show biz and enormous unexpected wealth. Just to imagine this simple Bucks County schoolteacher in the same room with Josh Logan the play doctor is to see the immovable object being tested by the irresistible force. Michener retreated into an impregnable fortress of work. He produced forty books, traveled incessantly, ran for Congress unsuccessfully, and was a member of many national commissions on a remarkably diverse range of topics. Although he lived his life in a simple Doylestown tract house, he gave away more than $100 million to various charities and educational institutions.

In his 91st year, he was on chronic renal dialysis. He finally told the doctors to turn it off.

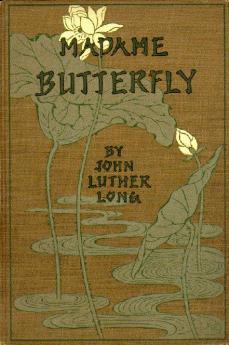

Madame Butterfly (2)

|

| John Luther Long |

There are two ways of looking at the love affair of Pinkerton, the dashing Philadelphia naval officer, and Madame Butterfly, the beautiful Japanese geisha. John Luther Long wrote about it one way, while Puccini somehow portrays it differently, even though Long collaborated on the Libretto of the opera. Puccini, of course, was himself a famous libertine, tending to follow the typical belief of such men that women somehow enjoy being victimized. Long in real life was a Philadelphia lawyer, trained to keep a straight face when people relate what messes they have got into. If you know the story, you can see Long in the person of Sharpless, the consul. Sharpless is definitely meant to be a Philadelphia name.

|

| Madame Butterfly |

Long was one of the early members of the Franklin Inn, and it is related he wrote much of his successful play at the tables of the club on Camac Street. David Belasco was the "play doctor" who knew how to make a good story fill theater seats. Even after Belasco's polishing, the play came through as a portrayal of the well-born gentleman who had been trained to regard foreign girls as just what you do when you are away from home. His real girlfriend, the beautiful Philadelphia aristocratic woman in a spotless white dress, was the sort you expected to marry. In just a few sentences of Long's play, this woman comes through as just about as distastefully aloof to foreign women as it is possible to be while remaining rigidly polite about it. Butterfly sees this at a glance, knows it for what it is, and knows it is her death. Her duty immediately is "To die honorably, when one can no longer live with honor".

It is Puccini's genius to take this story of how two nasty Americans destroy an honorable Japanese girl and using that same story with the same words, make it into a romantic woman being destroyed by a hopeless, helpless love affair. The power of the music overwhelms the story and sweeps you along to the ending. Even if you feel like Long/Sharpless, dismayed and disheartened by watching some close acquaintances doing things you know they shouldn't.

When Puccini's opera comes to Philadelphia every year or so, the Franklin Inn has a party for the cast, one of the great events of the Philadelphia intellectual scene. Somehow, the full intent of Luther Long's work never seems to come out.

The American myth of the cowboy has much more Philadelphia flavor than one would suppose, considering the far-western location of the cows, the New York origins of Teddy Roosevelt, and the implication of southern aristocracy running through the dispossessed gentlemen riding the purple sage. The myth of the noble cowboy is behind much of what elected Ronald Reagan, the Californian.

Nevertheless, the Homer who started this epic Iliad was Owen Wister of Seventh and Spruce, Philadelphia.His book The Virginian might be summarized in a single quotation, "When you say that to me, smile." Behind that, of course, was Wister the lion of the Philadelphia Club rebuking his peers. The real theme was "I searched the drawing rooms of Philadelphia and Boston for the gentleman. And I found him on the frontier."

|

| James Fenimore Cooper |

Part of this complex theme is the underlying outdoors fraternity linking cowboys and Indians, tracing back to James Fenimore Cooper of Camden, NJ ennobling the noble savage in the Last of the Mohicans. Fair treatment for the natives has long been a strong Quaker theme, tracing back to William Penn's deep wisdom about colonization, and also personified in Corn planter the thoughtful Chief of the Iroquois, or Joseph Brant the scholarly Indian leader who translated the Bible, charmed the English monarchy, and then returned home to massacre the town of Lackawaxen. There's a theme here of shooting the circling Indians off their ponies, take no prisoners, mixed with the tragic white woman who falls in love with the equally tragic Indian brave, all doomed from the start. There's the sheriff with a shady past, going forth to shoot it out with outlaws while his Quaker wife watches out the window, because he is true to the Code of the West. Grace Kelly was surely no Quaker, but the Philadelphia hint is unmistakable.

It may take a century or more, but some American Homer is surely going to write the definitive epic based on this story. Meanwhile, Zane Grey tried his best. His version has a lot of Philadelphia in it, and not only because he went to the University of Pennsylvania on a baseball scholarship. He graduated from Penn as a dentist, practiced in New York for six years, and hated every minute of it. Writing cowboy stories in his spare time, he gladly quit dentistry after his first publishing success, and moved over to Lackawaxen, PA to write in the woods. Lackawaxen is a great fishing spot, and was once a flourishing resort community at the confluence of the railroad and canal systems, now long since decayed and gone. He lived there for fifteen years, and asked to be buried there. His home is now a museum.

Pearl Grey became Zane Grey by way of P. Zane Grey, DDS. He had been born in Zanesville, Ohio, the son of a Quaker mother who belonged to the founding Zane family, and a preacher-farmer father who had insisted on the dentistry idea. All his life, Zane Grey was a vigorous sportsman, most unlikely to warm to an effeminate name like Pearl. Or gentle Quaker ways, either; but like his cowboy heroes he was obedient to his code. Most of his life he managed to go fishing more than two hundred times a year, and produced two thousand words of writing almost every week. He wrote a hundred thousand words a year, and kept it up for thirty years. He published sixty books in his lifetime, and thirty more of his books have appeared since his death. His material was the basis for forty movies, and many short stories. Six of his books are about fishing, but mostly he wrote sophisticated variations on the theme of the wild West, the cowboy true to his code, and the noble savage. He was the first American author to become a millionaire from his writings. It seems sort of a pity that he was overtaken by the pressures of commercial success, and consumed by his extraordinary drive and diligence to the point where very little time was left for the Great American Epic of the West. He lived in California for many years, but it seems unlikely there were enough hours in his day to shake loose from Quaker origins.

The same is true of Ronald Reagan and his Iowa origins, but somehow that does not capsulize what the American cowboy represents. Somehow there is something in common about the former Confederate cavalrymen who were the early cowboys, the Quakers befriending the Indians, and the Iowa boy who was to negotiate the end of the Cold War with the Evil Empire. It is somehow a matter of remaining true to your roots while dealing fairly with strangers. It lies in Reagan's motto as much as the Virginian's barroom warning. Trust, but verify.

William Penn Conducts a Witchcraft Trial

|

| Salem Witch Trials |

When trials for witchcraft are mentioned, most people think of Salem, Massachusetts, where 19 people were hanged as witches and hundreds were imprisoned, in 1692. The Salem trials were apparently provoked by a minister from Barbados, and it is thought the uproar about witches in America was in part related to encountering the spiritualism of the Indian tribes. Whatever its origins, the issue has been in the background for a long time, and occasionally even surfaces today in accusations of "Satanic rituals."

There were trials for witchcraft in New York in 1664, in West Chester in 1672, and in Princess Ann county of Virginia. But the trial of central interest to Pennsylvania occurred in 1683, when Governor Penn presided over it, himself. Pennsylvania had adopted British laws, including one from James I concerning the crime of witchcraft, so Penn probably had little choice but to hold the trial. His fellow judges were his Council; there is little doubt the outcome reflects his opinion.

The accused were two Swedish women, Margaret Mattson and Yeshro Hendrickson, who pleaded not guilty. Numerous witnesses told vague stories, and Mattson's daughter expressed her conviction of her mother being a witch. Governor Penn finally charged the jury, which brought in a memorable verdict. The defendants were found guilty of "having the common fame of a witch" but not guilty in the manner and form.

There are times, and this was one of them, when it is not useful to be overly precise in your meaning.

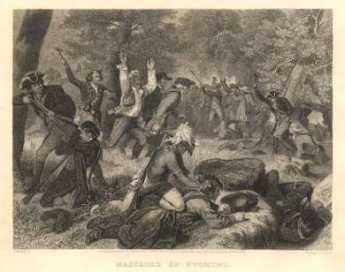

The Wyoming Massacre of July 3, 1778

|

| The Wyoming Massacre |

The six nations of Iroquois dominated Northeastern America by the same means the Incas dominated Peru -- commanding the headwaters of several rivers, the Hudson, the Delaware, and the Susquehanna, as well as the long finger lakes of New York, leading like rivers toward Lakes Ontario and Erie. They were thus able to strike quickly by canoe over a large territory. Iroquois were quite loyal to the British because of the efforts of Sir William Johnson, who settled among them and helped them advance to quite a sophisticated civilization. It even seems likely that another fifty years of peace would have brought them to an approximately western level of culture. Aside from Johnson, who was treated as almost a God, their leader was a Dartmouth graduate named Brant.

Brant, The Noble Savage

The mixed nature of the Iroquois is illustrated by the fact, on the one hand, that Sachem Brant translated the Bible into Mohawk and traveled in England raising money for his church. On the other hand, his biographers trouble to praise him for never killing women and children with his own hands. British loyalty to these fierce but promising pupils was one of the main reasons for the 1768 proclamation forbidding colonist settlement to the West of what we now call the Appalachian Trail, which on the other hand was itself one of the main grievances of the rebellious land-speculating colonists. The Indians, for their part, saw the proclamation line as their last hope for survival. After Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, the Indian allies were free to, and probably urged to, attack Wyoming Valley.

It is now politically incorrect to dwell on Indian massacres, but this one was both exceptionally savage, and very close to home. The Iroquois set about systematically exterminating the rather large Connecticut sub-colony and came pretty close to doing so. Children were thrown into bonfires, women were systematically scalped and butchered. The common soldiers who survived were forced to lie on a flat rock while Queen Esther, "a squaw of political prominence, passed around the circle singing a war-song and dashing out their brains." That was for common soldiers. The officers were singled out and shot in the thigh bone so they would be available to be tortured to death after the battle. The Wyoming Massacre was a hideous event, by any standard, and it went on for days afterward, as fugitives were hunted down and outlying settlements burned to the ground.

It's pretty hard to defend a massacre of this degree of savagery, but the Indians did have a point. They quite rightly saw that white settler penetration of the Proclamation Line would inevitably lead to more penetration, and eventually to the total loss of their homeland. The defeat of a whole British Army under Burgoyne showed them that they were all alone. It was do or die, now or never. Countless other civilizations have been extinguished by provoking a remorseless revenge in preference to a meek surrender.

Fair Mount

|

| THE FAIRE MOUNT |

Although the Art Museum now dominates the end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the earlier focus of the acropolis once called Fair Mount is just down the hill behind it, in the old Grecian complex of the Philadelphia waterworks. When the Schuylkill was dammed at that point, the effect was to calm the rapids, drown the falls at Midvale Avenue upstream, and turn this portion of the river into a placid fresh-water lake. Fairmont Park was then created upstream in an effort (originally stimulated by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia) to reduce pollution of Philadelphia's water supply going into the pumps at the Waterworks, by replacing, with parkland, the wards, and industrial slums at the terminus of the canal bringing anthracite from upstate. The result was the creation of an ideal place for public boating and skating.

The transformation of this area can be seen in retrospect as an impressive civic response to economic upheaval. The War of 1812 (by cutting off ocean access to bituminous via the Chesapeake) had first forced Philadelphia to use anthracite hard coal, and the discovery of anthracite's superiority in making steel caused a continuing reliance on it and the canals

|

| Philadelphia's Water Works |

that brought it here. By 1850, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad made the canals obsolete and created this splendid opportunity for urban renewal. The waterfalls had created a natural boundary between industry oriented to upstate coal and other industry oriented to oil and commerce coming up Delaware. It is a great pity that the lower section of the Schuylkill, once so famously beautiful, has never stimulated the same vision and imagination in response to the eventual decline of the industrialization which defaced it.

To return to Boathouse Row, a large azalea garden starts the Park, and then the East River Driver winds along the attractively landscaped riverbank. Just beyond the azalea garden, the first of ten Victorian-style boathouses starts the home of the Schuylkill Navy, an association of rowing clubs which are now a century and a half in residence there. When the Schuylkill auto expressway was created on the other side of the river, someone had the bright idea of decorating the rowing houses with lights along their edges in the manner used for Christmas decorations in South Philadelphia, especially on Smedley and Colorado Streets. Ever since the entrance to Philadelphia from the West has become one of its most arresting beauties.

|

| BOATHOUSE ROW |

Add a few cherry blossom trees in the spring, and you have quite a memorable centerpiece. Rowing sometimes called crewing, or sculling, is a central focus of Philadelphia society, and is curiously not something in which the city can claim to be first or the oldest. As you might expect, "regatta" is a word invented in Venice five hundred years ago, there are records of rowing races as far back as 400 BC, and New York -- ye Gods! -- had the first American boating club. The Philadelphia Schuylkill Navy was formed as an association of rowing clubs in 1858, and the oldest member, the Bachelor's Barge, was only formed in 1856. The development was largely spontaneous and is said to have been briskly stimulated by a beer garden nearby, run by a former Philadelphia sheriff. About the same time, the British became crazy about the sport, having the Henley Races as the most famous regatta in the world, and both the Australians and the Bostonians occasionally have the largest, most expensive, most widely advertised regattas. Foo. Philadelphia has the Schuylkill Navy, and it is central to our existence.

There are a couple of things which are unique about rowing. In the first place, it is hard to think of a way to cheat. You can hire engineers to redesign the shape and size of your boat, but engineering really doesn't make a lot of difference once the basic development of oarlocks and movable seats was perfected. A good boat can cost as much as $30,000, but that is large because all boats approach the limit of speed. If you have heavier or stronger oarsmen, it doesn't make that much difference. What matters is coordination, and in the longer boats, teamwork. Pull up with your shoulders, push with your legs, don't start with your buttocks, the art of rowing involves your whole body. The greatest champion of all time, Edward "Ned" Hanlan,

|

| EDWARD HANLAN |

only weighed 155 pounds. Not only was he world champion from 1876 to 1884, he was undefeated in any race during the last four years. True, he was born in Toronto, and eventually he was thrown out of polite Philadelphia racing for deliberately ramming another boat, but those are private Philadelphia comments, not something you want to talk too much about. The whole secret of rowing is to manage the fact that the boat travels farther between strokes than while the oars are in the water; if you row too fast, you actually slow the boat. There are two other Philadelphia names associated with the Schuylkill Navy. One is Thomas Eakins, the great American painter, one of whose most famous pictures is that of Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (on the Schuylkill). The other name is Kelly.

John B. Kelly of Philadelphia won two Olympic gold medals in 1920 and did it within one hour. He won a Third Olympic gold medal in 1924. But when he tried to race in the Henley Regatta, he was declared ineligible to row, because he had worked with his hands (summer work as a bricklayer), and thus could not really be called a gentleman. Anyone who has ever heard Irishmen talk about Englishmen can imagine the reaction this caused in the Kelly family. The resentment took the form of pushing his son, Jack, into racing, and in 1947 John B. Kelly, Jr. won the Diamond Sculls at Henley. Meanwhile, the father vindicated himself in other ways. The firm of Kelly for Brickwork was an enormous financial success, right up there next to Matthew H. McCloskey and John McShain, the political builders of the Pentagon and numerous other government buildings. John B. Kelly unsuccessfully ran for Mayor of Philadelphia in 1935 during the 75-year period when Philadelphia Mayors were always Republicans, but for decades was in the much more powerful position of head of the local Democratic party. The Republicans at that time would meet for lunch at the Union League, and so John Kelly reserved a lunch table at the Bellevue Hotel, next door, where he could be seen holding court every day.

|

| John B Kelly |

The result was not entirely favorable for the Bellevue; more than one wedding reception was rescheduled to some other hotel in order to avoid the Democrat taint. But you always knew where you could find Kelly at lunch, and it was fun to watch the various minions come forward to the table, almost as if they were in chains, to pay homage which involved provoking loud laughter from the great man with a salacious joke. The rowing clubs are mostly big barns with old boats high up on the walls, and silver cups and wooden memorial plaques lower down. They have lockers and showers, but no dining rooms, except at catered in the evening for parties. For a century, no women came there, but now almost half of the rowers are female. Membership is not difficult to obtain, although you have to be good to get on the club teams, and the dues are not expensive. If you show promise, you are expected to spend most of your waking hours working at it. Jack Kelly was famous for rowing three hours every morning, going to lunch, and then coming back for a couple of hours of more rowing. That doesn't leave much time in your life for anything else, so the friendships developed among active club members are very strong, just like the horsemen over at the City Troop. They sort of life in the past a little, with many anecdotes about a skull that broke apart and sank in the midst of a race, or a race that was lost because of too much recreation the night before. The lingo has to do with the fine points. A race can be between "eights" or "fours", or doubles, or singles. It can have a coxswain, or not, and be coxed or unboxed. When a pair of rowers have two oars apiece, it is the normal arrangement. A much more difficult boat to control has two rowers, with one oar apiece. Like Hercules or Achilles, stories are told of Hanlan, great Hanlan, who sometimes would win a one-mile race by eleven lengths. Or who would get so far ahead of his competitors that he would lie down in the boat and wait for another boat to catch up -- and then race ahead to beat him. This sort of person can be a little hard to take, and it is privately muttered that Hanlan was sent off to Australia, where people do that sort of thing more commonly.

The Bay of Fundy.

The Bay of Fundy.

Quakers serve, without fear or favor.

Quakers serve, without fear or favor.

It is Puccini's genius to take this story of two nasty Americans destroying an honorable Japanese girl, and using the same story with the same words, make it into a romantic woman destroyed by a hopeless, helpless love affair. /br>

It is Puccini's genius to take this story of two nasty Americans destroying an honorable Japanese girl, and using the same story with the same words, make it into a romantic woman destroyed by a hopeless, helpless love affair. /br>

Owen Wister may have invented the theme of the noble cowboy, but Zane Grey made it famous.

Owen Wister may have invented the theme of the noble cowboy, but Zane Grey made it famous.

Philadelphia's acropolis is Faire Mount, where the Art Museum marks the entrance to Fairmount Park. Stretching beyond is Boathouse Row and its rowing races. When the azaleas are in bloom, it's the match of any place in the world.

Philadelphia's acropolis is Faire Mount, where the Art Museum marks the entrance to Fairmount Park. Stretching beyond is Boathouse Row and its rowing races. When the azaleas are in bloom, it's the match of any place in the world.