3 Volumes

HEALTH SAVINGS ACCOUNT: New Visions for Prosperity

If you read it fast, this is a one-page, five-minute, summary of Health Savings Accounts.

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Consolidated Health Reform Volume

To unjumble topics

SECTION FOUR: New Health Savings Accounts

The project combines several concepts developed in other chapters, but is ready to be considered as a whole.

It turns out that working age people support the other age groups so heavily the two cannot safely stand alone. The funding advantage enjoyed by people 21 to 66 is weighted down by payroll deductions for Medicare, which are only half as large as the 50% government subsidy of Medicare. The overall effect destabilizes every age group. Only the 44% who are members of large employee groups are able to fund themselves, assisted by federal tax subsidies and local hospital discounts. The hidden Medicare deficit thereby threatens the whole system, and should have been addressed decades ago.

Seeing the frail finances of our proposal and recognizing the major contribution of Medicare subsidies to it, we added some features to N-HSA, to make it viable. They are explained in the following section, and make the main reason it is not possible to eliminate them in the spirit of compromise. Taken alone, some of the proposals may help. But unless the Medicare deficit is addressed in some way, the main problems will remain threatening.

Accordingly, the plan was revised to include an optional substitution of catastrophic health insurance for Obamacare, and a first and last year of life redistribution of costs to working generations. That somewhat left poor people out of the equation, so it was proposed to fund indigent people as individuals rather than through linking specific programs to them.

Nevertheless, planning such a project is worthwhile. It turns up several issues which will surely arise, even if we don't know when. That's particularly true with children, where a workable and controllable plan is offered. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first achievable proposal to be offered for children. It may well require modification, but I consider it to be a major advance just to appreciate how difficult the funding problem has always been, and how underestimated. Like everything else, it is linked to Medicare but not exclusively.

N-HSA, Bare Bones (2015 Version)

Explanations and arguments, later. Here's the skinny on N-HSA, the plan I believe is ready to put before Congress.

CATASTROPHIC HEALTH INSURANCE

1. Everybody is assumed to have a Classical Health Savings Account. If it isn't funded, it only exists in theory.

2. Everyone who has an HSA is now required to have high-deductible catastrophic healthcare insurance coverage. This should be changed to optional coverage, which becomes mandatory if the HSA is funded in its non-escrow partition.

3. Money deposited in the non-escrowed partition may be used to pay the premium of high-deductible catastrophic insurance, making the premium as an effective tax exempt as if an employer purchased it.

4. If employer-purchased health insurance loses its tax exemption, this feature may be re-examined.

MEDICARE BUYOUT

(1. Everybody is assumed to have a Classical Health Savings Account. If it isn't funded, it is inactive.)

5. A newborn child is funded $50/yr privately, or at public expense if indigent. Payroll deductions are then added.

6. The money is passively invested in an escrowed portion of the child's HSA as a total domestic stock market index fund, becoming available for a Medicare buy-out at age 66 (together with accumulated payroll deductions), with the alternative of conversion into an IRA after payment of taxes. Assumed gross income rate: 11%; assumed net of inflation and transaction costs: 6.5%. Average duration: 66 years.

7. Assumed Medicare buyout price: $ 48,336 plus payroll deductions, of indeterminate amount, probably $37,000. Assumed public and private net cost: zero or near-zero (readjust #5. appropriately)..

FIRST AND LAST YEAR OF LIFE REIMBURSEMENT

8. A second escrow fund within the individual's HSA is designated to generate the funds to repay the original payer of the first and last years of life cost, using the average Medicare cost basis, thereby lowering the first-payer premiums and/or buy-out costs.

9. This has a little net cost effect at first but tends to spread the cost away from poorly financed age groups without matching increase for the working age group.

10. Estimated cost: $20/yr.

INFANTS AND CHILDREN

11. Everyone is assumed to have or is assigned, one grandparent and one grandchild. Mis-matches are pooled, or reassigned on request.

12. Grandparents are expected to bequeath the left-overs in their HSA to their grandchild's HSA, up to the limit of one child's average cost for the first 21 years of that child's life. This transfer is deemed to occur at simultaneous birth and death, and appropriate inter-fund loans or transfers are made to accomplish this.

13. This bequest does not take place to the generation who have already achieved age 21. Grandparent contributions in the first generation are pro-rated as of age 50.

14. The bequest is invested in an escrowed portion of the child's HSA as a total domestic stock market index fund and transferred to his grandchild's HSA at birth for the purpose of funding. Assumed gross interest rate: 11%; assumed net of inflation and transaction costs: 6.5%. Average duration: 110 years..

INDIGENTS AND OTHER SPECIAL CASES

15. One of the great disappointments of the Obama plan is that it made health insurance mandatory, but left thirty million uninsureds. It may well be true that prison inmates and mentally retarded are so different from each other, they would be better served with specialized programs than one-size fits all.

16. Furthermore, most poor people are only poor for a portion of their lives, rising or falling with circumstances.

17. And finally treating poor people as an underclass with an attached funding source makes it impossible to have more than one program serve them. Therefore, it seems much better to have a separate agency which addresses their poverty based on their own demonstrated preferences, than to pick winners and losers among agencies to help them.

New HSA: One Potential Solution, Several Unsolved Issues.(2014 Version)

Could a health plan stand alone, without including working-age (21-66) participation? The answer is probably negative because the demographics are: age 21-66 supplies nearly all the money for the rest to use when they have sickness expenses of their own to worry about. Under present circumstances, the non-working subgroup could not include subsidized costs without coordinating with Obamacare, which might now contain as much as half of the healthcare costs. And as the Obamacare program evidently did, we came to recognize the thirty million uninsureds have such unique needs, they are probably unsuitable for any "one size fits all" solution. Probably only a demonstration project could finally establish a final answer, but even that would take decades. Politicians are not likely to commit such huge resources without more likelihood of success.Since these conclusions could have been reached without many studies, it seems a pity they were not given more consideration before implying universal coverage would be an outcome of the Affordable Care Act. For one thing, the numbers are too large. There are about thirty million Americans who are unsuitable for anything but a subsidized program if you only include the mentally and physically handicapped, prisoners in custody, and illegal immigrants. Since there is already an imbalance between the working well and the non-working sick, thirty million extra is just going to unbalance things more. The finances of Medicare are perhaps even more precarious than for the employed population, but there is too much public goodwill for Medicare to permit much experimentation. Decades of concealing these deficits are now returning to haunt the prospect of fixing them by any imaginable cross-subsidy.

Nevertheless, this book is a product of examining each step of the American health financing system. It may have missed some things, but it tried to be systematic. Although the attempt was made to cobble together a program for everybody omitted from the Affordable Care Act, we eventually gave up the effort as unachievable. Students of health economics may find our reasoning to be of some interest, so the essential remnants are printed in this chapter.

But one idea did emerge from this effort, which is put to work in the final synthesis in the last chapter. If it is workable, it might unravel the knotted mess of the rest of the system. Financing the health costs of children blocks any one-size-fits-all system, pretty stubbornly, and to a greater degree than most of us realized. Some students solve the problem by dismissing their costs as trivial. They are not. Health care costs up to the 21st birthday are said by CMS to be 8% of the total lifetime costs. Since prefunding is impossible, and the legally responsible parents have precarious expenses themselves as a group, attempts are made to create family insurance plans. But since one of the two breadwinners is often impaired by the process, half of the revenue source may abruptly appear or disappear. There is a trend toward small families, but respectful provision must be made for big ones, too. With unstable family structures getting more common, and essential rights and freedoms involved, no one is really proud of the present finance designs. When you potentially start with a $27,000 deficit for every new entrant into the employment pool, there isn't much room for innovation. Nevertheless, we developed a proposal for dealing with this problem. It's at least good enough to display in public as something which will work financially if the public can tolerate it within its social structure. I anxiously await public commentary.

In summary, it welcomes living, breathing grandparents back into the family structure. The great difference in generational ages is employed as a source of extra years for compound interest to work. The cost is presently evenly balanced between generations: one grandchild per grandparent. Because of the long period of compounding, the overall cost is less than $100 per child, not counting any net revenue from present funding sources. It thus seems fairly safe to assume it becomes self-supporting in the very long run. Even the transition costs seem containable to the age group 40-66 at about $600 total per person over three years. It would be a godsend and a bargain if it can withstand criticism. And by lightening the family's load at a crucial moment, it might make feasible a really radical readjustment of healthcare finance. That one can be found in the very last section of the book. It's a composite of ideas, all of which are enlarged upon in different sections of the book. And even I did not anticipate where it would come out.

Proposal for Health Savings Accounts, Extended (N-HSA, 2015 Version))

On June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court announced its decision upholding the status quo of the Affordable Care Act. As Justice Jackson once put it, "We are not final because we are infallible, we are infallible only because we are final."

It would thus appear that some or all of Obamacare will continue at least until the next presidential election. For now, the Affordable Care Act is the Law, and so my immediate reaction was to propose a health care program to take care of everything else, leaving a deliberate gap from 21 to 66 untouched for whatever might be coming from the Administration, because it seems so unpredictable. What that leaves is childhood care and Medicare, plus thirty million special cases, like prison inmates, illegal immigrants, and disabled. A good case can be made that these groups differ so much, it would be better to employ five special-purpose programs rather than some one-size-fits-all approach. However, they do share some common features and could be better integrated. For the most part, the government is their ultimate source of revenue. They are all limited in their freedom, so more supervision of the care they deliver is required. And, especially for children and prisoners, they will eventually be entitled to some of their money back at a later time. In some ways, the government acts like their trust officer.

So a Health Savings Account might well be generally suitable since they all might need a trust officer and a guardian angel resembling a Judge of the Orphans Court. In all the cases, there could arise special needs in their management for an accountant, a doctor, and a Judge. Foreseeing a triumvirate for supervision, and an HSA for storing the funds, the issue then arises whether it is superior to have a federal system or a more local one. Let's forget the Civil War; the federal approach confers uniformity, the state approach confers more flexibility for local control. In turn, the federal approach provides an escape hatch from local preferences. Obviously, federal prisoners will have federal supervision, and state prisoners will have state supervision, although it is questionable whether the source of the funds has much to do with the best form of supervision. Money talks, however, so this issue is probably not debatable. Nor is the issue of co-mingling of funds; the answer is a loud No. In fact, turf issues probably lead to the same response in most of these programs. In the cases of prisoners, the government must supply all the medical care, not just part of it, so voluntary Catastrophic insurance is unsuitable. All in all, you would have to ask what problem we solve with all this quarrel; ultimately you must answer for whether this new supervision is or is not superior to existing ones.

That leaves a Health Savings Account as a vehicle for funds, adding some income and possibly reducing some costs. To some extent, the HSA relies on individual responsibility, and all these people potentially have some loss of individual responsibility. Just as some Orphans Courts seem to be run by angels, others are a sickening mass of corruption, and there is no reason why this would be much different. The situation may possibly call for a blue-ribbon panel of experts to review and recommend, but scarcely calls for action to restructure everything. And it is doubtful whether the similarities of these different groups of people are greater than their differences. All these ideas have some merit, but seem more appropriate to individual adjustment, than to nationwide debate.

That is, the practical residual is addressing the healthcare of children, and the elderly. It seems-- to some people-- too soon to propose privatizing Medicare, since it has not sufficiently completed the process of shifting most illness costs from employer-based to itself, and has not even begun the process of shifting healthcare costs to retirement costs. Both shifts will probably occur in the next fifty years, but right now, the future of program planning is too unstable to build on. Its core problem is an inability to afford the 50% government subsidy, and yet there is continuing sentiment to extend that subsidy to everybody with a "single payer" system. Fighting a battle of perceptions like that is too daunting to attempt. So what does that leave? Children.

Once you narrow the focus, you can easily see why financing the care of children has been avoided. No one has seen any way to pre-pay a newborn's health care expenses, which are reported to be 3% of the total, for the first year of life. You might as well make that 8%, and include all children up to the age of 21. The most immediate legal responsibility falls on parents who are themselves only marginally self-sufficient, many of them either unmarried or in unstable relationships. The only hopeful feature of their finances lies in the potential addition of 21 years of compound interest if funds can somehow be transferred to use that.

I propose we overfund Medicare just a little, compound the inheritance for (on average) 83 years, and transfer it (greatly enlarged) to a grandchild's HSA at birth. Adding the two, the transfer would have 104 years to compound, and thus would require only minute amounts of seed money. My calculator reports an investment of $42 at the start will result in growth to $27,559 in 104 years. That would assume an interest rate of 6.5%, tax-free, net of 3% inflation. The revenue wouldn't look like that for 83 years, because existing grandparents are of all ages, ranging from 40 to 100, and each one would be expected to contribute catch-up revenue from birth to present age and could stop contributing with the birth of a great-grandchild. But let's not get down into the weeds of smoothing out the payroll contributions to make the transition payments appear smaller; payroll deductions already do some of that. There's a long transition period, but the ultimate cost comes down to $42 per person per lifetime before you fudge the numbers. Meanwhile, a major problem which has defied planners for a century gets solved and reduces the insurance costs of everyone else who was invisibly subsidizing the system. You might even increase the birthrate, which some would applaud but others would deplore.

That results in no small effort, however, because extreme versions of our focus programs require a transfer of at least 68% of healthcare costs from people who are not seriously sick, to the places where costs more naturally concentrate. The longer we wait, the worse the problem could become because of demographics. That is the case for every broad-based plan ever proposed, but this is the first one to concentrate on nothing else because we are blocked from diluting sickness costs with the costs of well people. Since we cannot easily force well people to agree to funds transfer, we merely relieve them of the need to pay the costs and expect they will take advantage of the opportunity. Similarly, we cannot force sick people to make use of the program, so we must rely on their recognizing the advantages.

First Year and Last Year of Life Coverage. We start with the simplest case. Everybody gets born, everyone dies; there are no exceptions. Furthermore, these two years are the most expensive ones and are likely to remain so. Medical advances of the future may raise the costs of terminal care, but even that is uncertain, and costs may go down. It is likely to remain true that just about everybody who dies, dies at the expense of Medicare, so we start with firm data, readily available. To simplify boundary disputes, using the calendar dates of the first year and the last year eliminates that particular fuzziness. Furthermore, obstetrics and terminal care contain elements found in no other age groups, concentrating the scientific issues. When I first presented the idea to a medical audience, one wit rose to the microphone and recalled a town in Pennsylvania that passed a law stating: "Every fireplug in the town must be painted white, ten days before a fire." He was, of course, quizzing me how you knew when the last year of life began. The answer is, you wait until the person dies and count backward, and you get the cost data from Medicare. Since everyone knows how imprecise hospital prices may be, it is probably sufficient to reimburse average terminal care costs for the year and the region. If the patient retains Medicare coverage, a simple funds transfer to Medicare simplifies both administration and coverage disputes.

The big problem is the long transition unless Medicare and the Administration should agree to prime the pump. Therefore, the program must remain voluntary, and may even have waiting lists at times, depending on its popularity. Certain tricks known to financial managers may help to shorten the transition to self-sufficiency. For example, CSS reports that the first year of life absorbs 3% of healthcare costs, and the last year about 6%. That is, $10,000 should be more than ample for the first year and $20,000 for the last year of life. That's assuming a lifetime medical cost of $350,000, the best estimate available. By externally supplementing the first deposits, the surplus after ten years can be applied to accelerating the funding of the last year. But even doing that could take twenty-five years to complete the process. Funds could be borrowed with a bond issue, of course, but eventually, that would raise costs and prolong the transition. "Sweet spots" can be found, but at the best, the transition is a long one, certainly spanning several turnovers of political power. Nevertheless, at the end of it, these pivotal medical coverages would acquire a major funding source, and other programs could experience a major reduction, up to 9%, in cost duplication.

In this, as in other parts of the book, we round off investment returns to 7% when we really expect only 6.5%. Using the old adage that money doubles in ten years at 7%, the reader can verify approximate accuracy by doing the sums in his head as he reads. The rounding errors also compound, so for accuracy it would be better to rely on a present-value calculator, many of which can be found on the Internet.

The Rest of Childhood, Seniority, and Permanent Unemployability. So that was the first Proposal 21: , to which the second one is a natural extension. All children are dependents of their parents, and the heavy costs of obstetrics (magnified by the unusual concentration of malpractice claims) make it impossible to devise conventional pre-funding schemes. Young parents are often strapped for funds, so the lack of pre-funding is a growing problem in a Society uncertain of its family structures. Therefore, we have devised the grandparent roll-over. Tort reform would improve but not eliminate this workaround. Therefore children are lumped with senior citizen costs, and hence to a gradual buy-out of Medicare.

The permanently unemployable are included by using surplus funds from the other two, mainly because there is no way to establish eligibility except by starting a program and seeing what it costs if you monitor it. Those may not seem like adequate reasons to lump them together, but it will be seen the details feel congenial, to do so. That is always a good sign in new proposals.

Multiple Programs in Multiple Years. The transition problem is always vexing in a new program, but reaches some sort of new limit when the ambition is to work toward uniformity and maximum patient control, across the entire nation; fragmentation always sounds easier. The temptation is always there to issue orders and threaten to use force, but it must be resisted. Furthermore, enormous cost savings are readily available if programs are multi-year, and the cost is a paramount issue, here. It's hard to beat compound interest, the longer the better.

To explain the reasoning of the grandpa transfer mainly requires the observation that grandparents are comparatively new re-entrants to the average family. It's simple (one grandchild's worth of costs, per person), it uses surplus cash after a grandpa has no further use for it, and it comes at an optimum time on the compound interest curve. It greatly stretches the lifetime for compounding, but it is also readily suited for a limitation on perpetuity. It even follows established family patterns, although families are under considerable stress, these days. True, it jumps over a new barrier for the first time, but it doubles the duration of compounding, skips over the issue of leaving a dark hole around the Obamacare age group, skips over the contentious issues of pre-funding obstetrics, simplifying a host of unnecessary red tape obstacles. And it reduces costs by half.

No Employer Involvement, No Obamacare Contributions. At first, it seems like a relief not to have to deal with the two thorniest issues of the past, but in fact, it doesn't quite do that. If the patient has duplicate coverage, there must be cordial negotiations to see which coverage should be dropped. And while significant savings can be readily demonstrated, there will be some residual revenues which have to be transferred along with the patient, or the new program will starve. The complicated systems we have evolved to facilitate cost-shifting will probably invalidate old statistics, and perhaps some old ideas. Transferring six percent of the gross domestic product is by definition a tedious, difficult task, even if you reduce it to four percent in the process. Everyone is hesitant to name the individuals who will lose their jobs, or their pensions or their seniority if the program shifts significantly. But if the savings aren't significant, what good are they?

New Health Savings Accounts (N-HSA)

On June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court handed down its opinion on King v. Burwell , essentially leaving the Affordable Care Act unchanged. Much will be written about this controversial opinion, but little of it would have to do with Health Savings Accounts.

If anyone is interested in my opinion about the contested language in the law, it is derived from reading Jacob S. Hacker's book about the passage of the Clinton Health Plan, called The Road to Nowhere . The plan as described by Hacker, was to plant deliberately conflicting proposals in the House and Senate bills, so the real proposal could remain concealed until the House-Senate conference committee meeting, where the versions meant to survive could be identified. The final result could thus be released when the press was absent, preferably on the eve of a holiday.It didn't happen in the case of Hillary Clinton's plan (which was never fully released), while in the case of President Obama's Plan, it was suspended in mid-operation by the death of Senator Kennedy. But the Senate version had been passed by a friendly Senate, so the House was forced to vote on an identical bill, to avoid returning to a conference committee convened by a newly hostile Senate. This version of the story fits the known facts pretty well and is reinforced by Hacker's subsequent membership on the Obama election team. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court's later decision constitutes an endorsement of a parliamentary maneuver which ought to be forbidden. Let's now break off this conjecture, and return to Health Savings Accounts.

My original intent in 2014 was to offer Lifetime Health Savings Accounts (L-HSA) in such a way the two programs (ACA and HSA) could be negotiated into a compromise that both could live with. In time, they would eventually evolve into hybrids that both would be proud of, or else lead the voters to state a clear preference for either one to be exclusive after they had a taste of both. Offhand, I could see no value for either one to be declared mandatory if that would still leave 30 or so million people uninsured. "Mandatory" did not seem like a helpful word to use, and often it seemed harmful to someone. In applying a computer search engine to the Affordable Care Act, I was unable to find a single use of the word "mandatory". Looking back on it, its premise was flawed but its intent was felt to be benign, so perhaps face-saving boilerplate was called for.

The central feature of the Savings Account has always revolved around the fact that youthful health care is usually cheap, while health care for the elderly is expensive. Many decades of tax-free compound interest at 6.5% would thus have been allowed to build up in some sort of escrow under both plans, until the age when healthcare really gets expensive. At that point, it would not matter which program it was assisting, and both sides would stop looking for a victory. By that time, I wouldn't be surprised if the deficits of the Medicare program had become so fearsome, and the debts of the program become so threatening, that both sides would be willing to consider modifications of Medicare. If not, subscribers to a buy-out had built up a six-figure retirement fund.

Medicare is already more than 50% subsidized by taxes and foreign borrowing, but the public scarcely knows it. I believe it is just a matter of time before the public realizes where it is going, but right now they see Medicare as getting a dollar's worth of healthcare for 50 cents if they think about it at all. I suspect it would take a full year or more of intense Congressional work to fill in the action details of a lifetime or lifecycle system, and maybe longer than that to re-direct public opinion. The proposal is voluntary, no politician dares to force it down anyone's throat. And the proposed incremental steps would also be voluntary. The investments would be in personal accounts, so no one could divert them for aircraft carriers. And the accounts would be lucrative, so no one needs to be afraid of their solvency.

Because compound interest on savings from the working years tends to rise after about age 45, a long period of Health Savings Accounts generates much more money than from a string of disconnected single years. Like the difference between term insurance and whole life insurance, you can't judge the improved investment of L-HSA by multiplying one C-HSA time your life expectancy, so it is a subtlety that two continuous programs would generate more funds than two separated ones.

Meanwhile, we have Classical Health Savings Accounts (C-HSA) which already have more than 15 million satisfied subscribers, steadily growing in number. Most of the Obamacare subscribers wouldn't want HSAs, and most of the HSA subscribers wouldn't consider the ACA plan, so total insured would increase. HSAs are described in the first chapter of this book, and in 35 years only about four or five improvements have come along, awaiting Congressional approval, but the bipartisan passage of them would calm the waters considerably. They need a tax deduction for the Catastrophic health insurance premiums, to make their owners just like everyone else. The easiest way to accomplish this is to extend permission for the Accounts themselves (which are tax-exempt) to purchase the catastrophic insurance which is required. Catastrophic health insurance is itself tangled in Obamacare regulations, which need to be revised, to deserve Presidential signature from any President. The annual deposit limits now need to be liberalized, and restated as total lifetime limits to account for the varying ages of new subscribers.

And new regulations need to accommodate the new phenomenon of passive investing, which is deservedly sweeping the nation, providing much lower transaction costs and higher average returns, which might be made still higher. Although HSAs are mostly self-administered, new investment managers are a little afraid of them, and well-established firms do not yet seem to recognize their enormous long-term potential. For these reasons, many early investors have been "savvy financial people", an image I am very anxious to see the change to "ordinary folks", without resulting in "high fees for rubes".

To return to the Supreme Court's King decision, the only version of HSA which is ready to go is the Classical one, which would still be improved by a few amendments, if the President is of a mind to cooperate. His own plan seems more or less in suspense, waiting for Big Business to emerge from its policy huddle, after two years of delay. Many tradeoffs and compromises can be envisioned for that coordination, of by far the biggest eligible group of subscribers. It is my commentary that employers' gift of health insurance in 1945 has long since been compensated for, by a corresponding drop in wages. So nothing but a tax exemption is left. The amount of money involved is so huge, it requires other issues to be brought into the discussion to avoid a stock market panic. It particularly needs to be emphasized that a loophole based on the corporate income tax rate is not at all -- not at all -- the same as an increase or decrease of corporate income at that rate. Getting a free lollipop at a 60% discount does not affect your company's income by 60%.

Nevertheless, the existence of fringe benefit tax dodges does create pressure to retain the high corporate taxes, and those taxes need to be reduced to keep our corporations from fleeing to tax havens abroad. My suggestion is to lower the corporate income tax in parallel with a comparable reduction of the employer tax dodge, a maneuver so delicate it ought to be overseen by the Federal Reserve, acting under a Congressional time limit. Such a proposal is so newsworthy it might well suck the air out of the room for Health Savings Accounts, and Obamacare, too. Everyone involved has an incentive to be cautious and reasonable, a difficult thing to be, during an election year. However, with prudence, breaking the logjam on the migration of American corporations to foreign locations could be the thing which suddenly gets everyone's attention.

New Health Savings Accounts (N-HSA)

Because it increasingly seems so unlikely a notoriously stubborn President would ditch his health plan at this late date, I turned my attention to seeing what could be done with using Health Savings Accounts for what's left. Obamacare is likely to be subject to twists and turns until after the November 2016 elections, and this administration has a history of preferring to operate out of sight. Therefore, my revised plan was to avoid the subject as much as possible, except for one thing. The savings in a portion of the Account would continue to accumulate as a tax-exempt investment account, available for extra medical expenses until age 66 when it turns into a retirement account. That is, an N-HSA account could exist untouched for as many as 45 years (21-66) without catastrophic backup insurance, or else if agreeable, with a catastrophic policy coordinated with an Obamacare policy. The purpose of this part of the structure was to provide a haven for a long-term buildup of funds, with as few financial drains on it as possible, while it stays out of the way. On the other hand, money seems no good if you can't spend it, so it needs some contingency exists.

It is possible to summarize a great deal of thinking by stating that it mostly can't be done. The evolution in healthcare has not reached the point where people aged 21 to 66 could save enough to support the rest of the population while taking care of their own health. In fifteen years that might become possible, but not yet. Even then, an additional thirty million people who are unemployable (prisoners in custody, disabled people, and illegal immigrants) would probably topple the system without some major reductions in the cost of chronic diseases (diabetes, Alzheimers, arthritis, emphysema, kidney failure) which might well take another fifty years. So we temporarily set this attractive idea aside.

Except for one thing, paying for children under 21. The system devised was to overfund Medicare slightly, gather investment income for a combined 104 years, and transfer the result to a grandchild or pool of grandchildren to pay for 21 years of healthcare. The grandparent transfers the money at the death after 83 years of compounding, but the child receives a lump sum at birth and erodes it to near zero by the 21st birthday. This is how 104 years are available to the next generation to grow a contribution of $42 to $27,000 while staying within the limits of the Law of Perpetuities. To do this requires passive investing of a total-stock index averaging 6.5% net of 3% inflation. According to records by students of the subject, the total stock market has averaged 11% returns for a century, in spite of wars and depressions. Right now, the main obstacle to achieving this is the community of middle-men in the financial world. It the problem continues to be a stubborn one, I advise taking delivery on the stock index security, putting it in a safe deposit box, and opening it decades later.

One issue comes up, that this system could produce unlimited amounts of inflated money by escalating the initial single payment. But it cannot do so if the account balance starts from, or must go to, zero. If loopholes are discovered, additional points of zero balance could be imposed.

Medicare Backup Insurance. In the original planning of Health Savings Accounts, it never seemed likely we would lack places to spend money earmarked for healthcare. However, 45 years really is a long time to have your money locked out of reach. The other side of this coin is the spectacular result of long-term passive investing. Just to throw in a couple of examples, the investment of $1000 at age 21 would result in a fund of $16,000 at age 66, and an investment of $1000 a year, every year from 21-66, would accumulate a fund of $246,375 at age 66, quite a nice retirement fund. And if you were lucky enough to live frugally, from 66 to 83 the $16,000 would grow to $ 43,800, and the $246,000 would grow to $680,165. If you grow uneasy about Medicare solvency, these sums would be nice to have in the bank. In effect, they could serve the function of catastrophic self-insurance, without the insurance.

As a matter of fact, it would be nice to include a provision that the Health Savings Account could dispense with the expense of catastrophic insurance when it grows to a point equalling it. It would dramatize the subtle transformation, from an account for drugstore expenses, into a serious investment tool. That won't happen soon, and it won't happen to everyone, but it is a realistic goal.

Healthcare for Children. Now, that leads into an entirely different direction. One of the perpetual headaches of designing health care finance is the fact that newborn babies are expensive. Part of that is due to inordinate malpractice costs for obstetrics, partly it is due to expensive care being devoted to premature babies and Caesarian sections. But mainly it is due to the parents being young people without much savings. It's pretty hard to design a pre-funded health care plan for an individual who starts the second year of life with a $10,000 debt.

His parents barely climb out of a financial hole before the child himself is ready to have children. As we have seen in earlier paragraphs, some frugal grandparents end up with more healthcare money than they can spend on their own health. American mothers average 2.1 babies apiece, and with a little fumbling it can be seen, that figure averages one grandchild per grandparent. If aggregate health care for children 0-21 averages $29,000, Grandpa could give a child a very nice start on life by rolling over his surplus at age 83 to a grandchild at birth -- if the laws permit such a thing, particularly if no family connection exists. (We'll have to leave unorthodox family sexual preferences to the matrimonial lawyers to sort out. )

With ingenuity, an additional 21 years can be added to the period of compound interest, and we've already shown what a difference that can make in an 83 (or maybe 93) year lifespan. In case you missed the point, when Grandpa relieves the cost of healthcare for a grandchild, the benefit is indirectly felt by the child's parents, although that isn't invariably true. Right now, the cost of a child's healthcare is the responsibility of the parent, so it's relatively fair.

Payroll Deductions and Premiums for Medicare. With 300 million citizens, a lot of exceptional cases can arise, and the foregoing probably doesn't contain enough incentives to start a stampede for N-HSA. Accordingly, let's consider forgiving the Medicare payroll deduction, in whole or in part, as a legitimate spending outlet. And if that isn't enough, consider waiving Medicare premiums. Both of these are legitimate health costs, so no one is violating the purpose of a tax deduction for Health Savings Accounts. Each one of them covers about a quarter of Medicare costs, so the funds are ample. (The present average costs of Medicare are about $180,000 per lifetime).

And finally, there's your Social Security contribution. SS isn't a medical cost, but it's a retirement cost, and that's what N-HSA could turn into. Reducing any or all of these expenses will free up a comparable amount of spendable income. If all else fails, consider abating your income tax. Income tax isn't a health expense, but it is often the largest item in a retiree budget. Reducing income tax could displace other funds designated for health costs, and hence indirectly could sometimes be considered a health cost, itself. There are plenty of ways to create savings with the government, and all you probably really need is their permission to do it.

To repeat, the purpose of all this is to find a way to subsidize the health expenses of children, which in my view is the unsuspected stumbling block for all self-funded lifetime proposals. Even the tax-evasive employer-based system gets into a tangle over it.

Subsidies for the Poor. We must conclude by mentioning poor people. It's, of course, true you have to start with some money to earn income from it. What are you going to offer poor folks, when the country is already deeply in debt? Well, it's practically impossible to say what Obamacare is going to do for them, although it will surely do what it can. The possibility of double-subsidies is still present when the situation is as unstable as it is, and the economy is as fragile as it is. So this proposal prefers to delay the subsidy discussion until Obamacare is also on the table.

To facilitate that discussion, this plan has been forced to organize the subsidy money for poor folks to come out of the age group 21-66, who are effectively the only real creators of wealth in the whole system. That coincides with Obamacare, and cannot be effectively discussed without including it. However, once it is coordinated, the subsidy to poor people could be quite substantial as a result of being placed at the far end of the compound interest curve and given enough years to work in an escrow account. If came to a showdown, the subscriber could take delivery on an index fund certificate and put it in a bank lockbox until it was needed. I propose separating subsidies from all healthcare and funding them independently. Independent of the intermediaries of their grants, that is.

To summarize, we start with a regular Health Savings Account with obstructions removed. In return for allowing the HSA to remain in the background, gathering interest, the HSA effectively assists Medicare. Assisting Medicare could mean helping in a Medicare buy-out, or it could be used to help Social Security. Or it could recirculate through Grandpa, to help the coming generation. An option for Grandpa to make the choice would simplify administration, but possibly unbalance something else.

Coordinating New HSA with The Affordable Care Act.

Starting with N-HSA We have just described the general outline of New Health Savings Accounts (N-HSA). Essentially, it consists of individual HSA funds for children, connected to Medicare by permitting the funds to sit in escrow from age 21 to age 66. However, the amount which can be accumulated during childhood is small, and the task it is asked to perform is large. Because children are so lacking in income, they can't be expected to accumulate much, even though their grandparents may have helped out. Consequently, that small amount multiplied by compounded income for 45 years, will probably only pay for one designated segment of the Medicare program, and it is unlikely it would be able to pay off much of Medicare's accumulated debt.

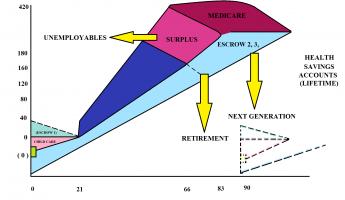

So, although it can be shown to be workable, it would look like a long run for a short slide, to an economically illiterate family. Meanwhile, its political enemies would likely describe it as meddling with Medicare, and its chances of achieving the necessary enablements would shrink. However, the grand discovery is, the Health Savings Account idea resembles how President John Adams once described his native Boston -- Every goose is a swan. Every problem we encounter, that is, seems to suggest an unexpected new improvement. Let's explain the three accompanying graphs.

Three Graphs. The top graph shows the situation, without either a bridge around or participation in, the Affordable Care Act. The HSA escrow comes to a halt for 45 years and then resumes with Medicare. There are two savings accounts, but each starts at zero and lasts two decades. One is an escrow account, unspendable until age 66.

The middle graph imagines the situation with a dormant escrow gathering interest during the 45 years. Notice the thickened blue escrow.

The bottom graph is a cutout enlargement of the transfer point for grandpa's gift, showing how easy it would be to adjust the escrow transfer from zero to $29,000. The difference between the extremes added to the escrow is the difference between solvency and riches. To imagine a small deposit spiraling out of control is probably a little fanciful, but for those who worry, here is a ready solution.

Adding Obamacare. If we achieve political consensus, and thereby add the subscribers from age 21 to 66 (the only age group which reliably produces real new wealth), the arithmetic suddenly transforms. The complete system from cradle to grave generates enormous surpluses. After studying this paradox for some time, I came to realize that what distinguished it from Lifetime Health Savings Accounts (L-HSA) was the two, eventually three breaks between programs, where the escrow fund could drop to zero, without some agreement to transfer it between insurance programs. If it drops to zero, the effect of compound interest rising at its far end is chopped off, and overall returns are much reduced. The whole idea unfortunately then becomes politically precarious and runs the risk of some small glitch somewhere unraveling it. To use our own descriptive terms, three Classical (C-HSA) funds are nice, but one Lifetime (L-HSA) is so far superior it raises grandiose questions of starting an inflationary spiral. But in a sense, the radical Right is correct. The changes to the Affordable Care Act must be drastic enough to generate public support for merging the radical plan of the left with a radical plan of the right, essentially making both of them unrecognizable. I'm no politician, but I can easily imagine the difficulties of that negotiation.

|

The Goose is a Swan. But I came to see that what makes it impractical is the same as what makes it so glamorous. The possibility of linking the healthcare fund to the stock market would likely be brushed aside by the explosions of a money machine -- the system as originally envisioned for L-HSA generates almost any amount of money you please. That's a pretty intolerable effect of inflation heedlessly disregarding any monetary standard, even a return of a gold standard.

But if the HSA is more or less denominated in index funds, it essentially has a monetary standard built in and could maintain it if someone held a meat ax in reserve. Some impregnable threat is needed to control the monster, and it is provided at the three linkage points, where the three existing insurance programs connect.

|

Three Meat Axes. The connection after the children's escrow fund is the most leveraged and therefore the most sensitive since we have already demonstrated how the difference between zero transfer between two funds, and the transfer of $27,000, is the difference between marginally paying Medicare bills, and having money to burn. If some totally reliable monetary angel could be discovered and put in charge of it, the discretion about inflationary consequences could be placed in one pair of hands.

But the history of inflation has been that even Kings, Popes and Emperors have succumbed to the temptations of such power. Remember, this fund is truly generating $350,000 of new wealth per person (in a nation of 300 million inhabitants) if it operates precisely as hoped, so it starts with some latitude. There are several Presidents of the nations of the world, who might fairly be suspected of raiding their own currency right at this moment, however. Wisdom suggests more caution is necessary. For example, Congress could permit a discretionary band within which the Executive branch could operate, perhaps in consultation with the Federal Reserve. That might permit Congress to create some very difficult hurdle for the process to jump, for widening the limits of the band, such as a Constitutional Amendment.

There's an End in Sight. And also remember, my colleagues in the research department are busy looking for a cure for cancer and Alzheimer's Disease, and I feel confident they will eventually have success. Just cure diabetes, schizophrenia, or birth defects, and our problem with Health Savings Accounts would transform into how to turn them off. In the meantime, we must modulate the ups and downs of medical costs which are steadily becoming less urgent. Take warning from the recent example of the price of tetracycline, which a year or two ago was 35 cents retail for fifty capsules, and suddenly jumped to $3.50 for a single capsule. And then with a new owner, jumped to thousands of dollars. If things like that continue to happen, we might be ready for another pet scheme of mine, the limitation of health insurance coverage to covering the first year of life, and the last year of life, by eliminating most of the disease in-between. Because of the helplessness of both these population groups, and the universality of the need for their coverage, in their case alone drastic interference with market mechanisms might appear justified, to those who are injured by them. The rest of us ought to have a say in something like that. But that's another book, for another time.

We're some way from seriously having that type of problem, so let's get back to details. For this purpose, paying patients arrange themselves into only three groups, children, working folks, and Medicare recipients. Thus there exist three breakpoints between these three programs for different ages, assuming Congress authorizes transfers between them, especially from grandparent generation to grandchildren, incidentally relieving the middle generation of a lot of cost-shifting. There is now so much (necessary) cost shifting, it is nearly impossible to sort out the cost numbers. So I won't try to do it, except in a sort of general way. Rationing is a sort of a lip-service concession to the wide-spread liberal endorsement of a single payer system, endorsing but without facing the resultant deficits in every direction. Instead, we encounter the worrisome potential for generating too much money, even though that is hard to believe without endorsing galloping inflation. There is little difference between external transfers -- between insurance plans, and internal transfers -- within one mega-institution -- except, in this case, one approach creates impossible deficits, and the other approach raises a real concern about inflation. A compromise might be devised, but it requires some sort of conciliatory response from both sides, for even a beginning.

Meanwhile, I don't scoff at the legal issues of who is responsible for those bills, if we destroy the family unit with exciting new social liberties. And I haven't forgotten the problem of corporate finance officers, who have run a confidence game for eighty years, making money for the stockholders by giving away health insurance to employees, as long as they can conceal what they are really doing. We've suggested in this book, we should offer the business a reduction of their corporate income tax to levels comparable to individual tax levels, in return for getting them out of the health insurance business. In a sense, it returns the favor of making a profit by giving away a service benefit, by -- generating revenue for the public sector in return for reduced taxes in the private sector. I'm entirely serious about offering major corporations a one percent cut in corporate taxes for each two percent reduction in fringe benefits tax exemption, down to the point where the top corporate income tax rate is equal to the average individual tax rate. That benchmark is selected because of the temptation otherwise created, to elect Subchapter C to S inter-conversions, exploiting such tax differences. The international corporate flight is another serious consideration. Meanwhile, it is always possible to equalize employee tax exemption by allowing HSAs to purchase catastrophic insurance through the HSA itself, if the law would permit it.

Inflation Protection. Q. Now, wait a minute. If we permit a money machine to be built, what is to prevent it from resembling the galloping inflation which ruined the Weimar Republic? And if we devise a way to keep the United States from going down that road, how do we prevent a hundred small foreign states (Zimbabwe, for instance) from doing it deliberately in order to use their sovereign status to acquire the index funds held by Health Savings Accounts?

A. You've almost answered your own question about Zimbabwe. Even without freely floating currencies, the markets are quick to detect changes in the value of the foreign currency. Zimbabwe can force its own people to accept pennies disguised as trillion-dollar bills, but everybody else avoids them, whereas bitcoins don't even have sovereign power. And as for our own domestic currency, I propose we enact a band of fluctuation in consultation with the Federal Reserve, within which the dollar can float, and beyond which the band may not be expanded without a Constitutional Amendment, again in consultation with the Federal Reserve. In two hundred years, the amendment process has only let one matter (Prohibition of alcohol) slip past, which had to be revoked after the experience with it. Almost every other indiscretion has proved to crumble in spite of the temptation to raid the cookie jar.

Watchdogs. Three breakpoints, one between each age group, with wildly different medical needs and financial viewpoints, need watchdogs. Since going to zero between any two of the three insurance programs could bring inflation to a halt, and since venality knows no political boundaries, I suggest each breakpoint be governed by a different political entity, composed of a board nominated by a different branch of government, and each ratified by a different process. It may or may not be necessary for them to share the same information agency, since think tanks are very popular right now, but may not continue to be. We will need another conference in a resort hotel to work out a paper but keep in mind that foreign powers will be anxious to infiltrate and subvert it. So maybe we need two conferences, one to review the other. After all, we are talking about 18% of the gross domestic product, and Benjamin Franklin isn't available anymore.

What's the Matter With Medicare? And Single-Payer?

With great reluctance, I feel I must discuss adding the option to buy out of Medicare. I am a happy satisfied patient of that program, and for many decades was a happy, satisfied provider of care under it. Prior to 1965, I practiced medicine for 15 years before there was a Medicare program, so I have something to compare it with. The main difference I see is the tremendous backlog of untreated chronic conditions which had built up during the Great Depression of the Thirties, followed by the war years. Let me describe it; but remember, my final conclusion is "Sorry, Medicare, but we've outgrown you."

In those early days, every mouth I opened hid snaggly teeth, every other eardrum seemed to be perforated. The smelly weeping varicose ulcers of the legs were hard to take, but there were hernias and gallstones galore. And hemorrhoids, and stomach ulcers. Most eyes seemed to have cataracts growing in them, the goiters were as big as grapefruit. From the doctor's point of view, the disease burden of the population was never going to be exhausted. We scarcely realized we were dealing with a backlog, and tended to believe this was just the way poor people had to live. In fact, we cleared out that backlog in ten years, scarcely realizing it was diminishing. Meanwhile, we built up another backlog, so to speak, of a population whose disease burden had been cleared away. Re-building that healthy reserve was a sort of ghoulish reserve against some blunder we could coast through. Because, like it or not, some people will neglect their health if we stop making treatment free.

If we now have another depression or war, we could probably coast through the lack of optional medical treatment for several years, believing all the while, the cost of healthcare was decreasing. Treating the backlog is one of the costs of Medicare which never seems to get counted, and doing away with it left us with an unmeasurable reserve of artificially healthy patients. And it wasn't just minor conditions with optional treatments. When I was a visiting consultant at Philadelphia General Hospital, it was not unusual to visit the autopsy room before we went to the wards, and the residents would present several, perhaps five, bodies on the slabs. Following that, we would go upstairs to the 40-bed wards and make rounds on the patients who might well occupy the slabs on another day, because they had been too far gone when they arrived.

Present day residents have little comprehension of the devastating severity of disease we had before us, and administrators have little idea of the change this has made in costs. When we needed all this equipment we often didn't have it; nowadays the residents have a lot of equipment they seldom use. Some of this would have improved without Medicare, but Medicare certainly hurried it up. You don't hear many doctors of my generation criticising Medicare.

Just what the patients thought of it all, is hard to judge. By the nature of things, the sick people were older than the doctors who treated them, and the doctors are now in their nineties. I get the feeling the old folks are deathly afraid Medicare will be stripped of funding in order to pay for the unaffordable Affordable Care Act. So they are ambiguous; they got a lucky break which they don't want to deny to younger people. But they seem to recognize the costs are unsupportable. They silently read the Sunday newspaper columns about the $10,000 pills for cancer. Like me, they see a two-page listing of hospital administrators making $4 million annual salaries, with the listing going down to $250 thousand per year before the newspaper runs out of space. The old folks know almost nothing about the Affordable Care Act, but they immediately recognize that such articles are written to stir up animosity to hospital costs. They don't know what to think, so they appear to have decided it is best to keep their heads low. All they seem to want is a chance to have their share of it, before it all goes away.

And they should feel the way they do. When Secretary Sibelius published the Medicare balance sheet, I was astounded to see the program is only 50% self supporting, the rest is borrowed from the general fund. And everybody knows the general fund is largely borrowed from the Chinese, who are in financial distress themselves, right now. Books are in print accusing the government of desiring more inflation, in order to cause effective default on our sales of Treasury bonds to (i,e, borrowing from) the Chinese. Medicare recipients showed little interest in the Obamacare debate, and therefore have almost no information about it. But they grasped the essential point, all right. Medicare is delivering a dollar's worth of healthcare for fifty cents. And everyone in Congress is scared to death to bring up the subject, for fear they touch the third rail of politics.

Aside from that rather considerable political matter, there are a number of basic flaws in Medicare. Medicare has a monopoly of healthcare for the elderly. It doesn't have to be mandatory. A 50% discount below cost would quickly make almost anything at all substantially mandatory. All monopolies inhibit competition, especially in adopting innovation, and all of them ultimately thrive on shortages. The breakup of the ATT monopoly unleashed a flood of pent-up innovation in the telephone field, for a familiar illustration.

The inevitable domination of a field by an extra-large competitor is dramatically illustrated by California's present dominance of insurance design. Essentially all new designs of insurance feel they must first conform to California's regulations, and if necessary just ignore the smallest states. That's a current example of what John Dickinson was afraid of at the Constitutional Convention. He was simultaneously Governor of Pennsylvania, one of the largest states, and of Delaware, one of the smallest. He knew what he was talking about, and essentially that is why we have a Senate with two votes per state, regardless of population. This analysis ought to be known as the Dickinson Concept, because it is one of the main reasons our Constitution has survived for two hundred years, while every single other constitution has floundered. Monopolies are usually very bad things, but in a very subtle way. And yet bigness is a sign of success in a company. It's a very subtle distinction.

In the case of healthcare, we have a nationwide system of one-price-fits all, making no distinction in price between good and bad care, or whether the patient lives or dies. Obamacare recognizes this flaw and has appointed a committee to look into fixing it. Lots of luck with that, because the nation recognizes the unwisdom of letting government pick winners and losers. It probably just can't be done acceptably. State-wide uniform prices are about the best you can do with either a command-and-control system or an insurance system. Haggling in a marketplace is treated with disdain, but it's the only way anyone has devised, to reward good quality. So, a nationwide Medicare encounters this problem, and enlarging it to nationwide single payer, would make it even more troublesome. Everyone can see that Wisconsin benefits when Illinois tries to do it.

Nationwide uniformity has some advantages, such as concentrating essentially all the deaths in one program for research, although the bigdata computer approach may eliminate even that edge. What a monopoly tends to do, is enlarge one institution's scope until it finally gets so top-heavy it collapses. How many corporations can you name who are a hundred years old? The curse of bigness is so powerful that only those who have experienced it, can anticipate it. The big gorilla dominates so insidiously, the competitors forget how to compete. Everything is wonderful, until suddenly it is terrible.

And finally, the greatest problem with healthcare is its design. By insuring the cheap stuff but running out of money when you really need it, we are killing the Canary in the Coal Mine. Front-end deductible reverses that perverse priority. It corrects a system that will only work if you eliminate most disease, big and small. The advance of science is relentlessly crowding serious illness into the age group over 66, and is eventually destined to trivialize medical care in younger healthier people. Eventually we will get, or possibly have already started to get, a system so focused on the present, it fails to look to the future. Eighteen percent of the gross domestic product is being transferred from people who will have never felt a wound, to the non-working minority over 66, who will eventually have serious illness all to themselves. The people who don't have much sickness are expected to pay for the old folks, who do. It's a prescription for rebellion, and perhaps some of the present travail is already a sign of it. I'm sorry to have to tell this to my fellow subscribers to Medicare, but if you become too expensive, the kids may ditch you. I'm already older than most people on Medicare, and you will notice I'm still struggling to design an alternative to this wonderful half-price bargain. It's tough, because even cutting the cost in half will leave the impression prices were unchanged. That's because the gains and losses were hidden in the public sector, with only the gains getting some publicity.

So, the conclusion is this. If the politicians are right and Medicare is untouchable, the main danger is its reputation will entice us to extend it further, as a "Single Payer" system for everybody. At a dollar for fifty cents, even an exorbitantly expensive system seems to be a bargain. So a last-ditch warning by implication is this: Follow the doctor's advice, in Latin, of Primum non nocere. If you can't make things better, for pity's sake, don't make things worse.

Medicare Buy-Out

Could Americans buy their way out of Medicare? Right now, no. In a few years, probably yes. A Medicare buy-out would have a few special complications. The transition to it might take thirty or more years, in view of the several ways it raises revenue and the varying ages of the patients involved. For example, from the time an individual starts his first job, until the age of 66, he is sustaining payroll deductions for future Medicare coverage. Also, from the age of 66 until he dies, he has Medicare premiums deducted from his Social Security payments. Each of these compartments aggregates about a quarter of the cost of the program, and the two methods keep more or less in balance over a lifetime, eventually paying half its cost.

The other half of the Medicare program cost is supplied through general tax sources, as a subsidy, and could continue to build up indefinitely. Eventually, an undeterminable portion of the subsidy is borrowed internationally, and that debt, like a credit-card balance, draws continuous interest. The Economist reports it would be more advantageous for the Chinese to buy American common stock. But using that approach, they would now own a fifth of the major corporations of America, which is politically unacceptable. Therefore, they bought American Treasury bonds. Depending on maturity, these bonds will eventually come due and must then be redeemed or refinanced. This arrangement can only continue with mutual consent of the two nations, and currently, the Chinese economy is shaky.

Moreover, it cannot be said the two funds will keep in balance. That's essentially true in bulk, but the actual revenue for each age cohort is largely based on its historical birth rate. Payroll deductions for the baby boom bulge have reached a peak and are about to decline to zero, whereas the Medicare premium bulge is just beginning, along with benefit payments. These repeated imbalances could prove troublesome to fund.

I wish I believed these receipts had been put into a bank vault, but in fact, they were likely co-mingled for general government expenses and spent long ago. Whether or not they are represented by accountants as paying for part of future Medicare expenses, or for current bridges and battleships, they are going to make a problem when the boomer bulge catches up with them. The formula will remain unchanged, but the proportion of payroll deduction will fall because the Millennial generation is fewer than the boomer generation, who are in turn more numerous than their parents as consumers of Medicare funds. The Treasury would certainly be concerned about any proposal to accelerate the payout to help a Medicare buyout. And even if an exchange of health funding is agreed to, the accounting problem of determining millions of balances of differing size is sure to be a headache. The balance in question is the net of 6.5%, less the rate on Treasury bonds, which could be either a positive balance or a negative one if the bond market and the stock market do not move in parallel. The unpredictability of markets is amply illustrated at present, when trillions of freshly printed bonds do not cause inflation, even for the mundane purpose of maintaining a stable currency. Even inflation targeting does not work as desired, currently reaching 1.5% when the Federal Reserve is trying to reach 2%.

In the longer run, Medicare buy-outs by the grandchild approach would stretch available funds over a longer time span, and augment them somewhat. Longevity is increasing, but the period of working life is not. People are retiring earlier, and they are entering the workforce later in life. Progressive taxation further reduces what working people have left over to spend, and eventually will make them less willing to support the protracted vacations of their children and their parents. So extra investment income will be needed, and shifting other savings around will probably relieve some of the pressure. Even so, it appears certain some elderly people will outlive their savings and must find a way to generate income with their leisure time. Along the same lines, we must also change the mentality of those who regard employment as a punishment to be avoided, but that is not my present topic. One small advantage of the unemployed Millennials is they are less likely to resist working long after they do get a job.

Summary of One Scheme of Medicare Buyout. Childhood health insurance, funded through health insurance for senior citizens. Owned by two people linked by redefining a birthday or some other strategy, all sounds like a peculiar idea. But let me persuade you to do a little math. At 7%, there are 9 doublings in a 90-year life. 2,4,8,16,32, 64, 128, 256, 512. That's rounding up on 6.5% and 85 years, which are closer to realistic estimates of future longevity and interest rate return, but no one can predict. Every dollar at birth (now redefined financially as the 21st birthday) is multiplied 289 times (the approximation process suggested 512). The grandparent aged 40 would have to add $450 to a sinking fund, and a grandparent aged 65 would have to contribute $27,000 to pay it in advance. Eventually, when things settle down and we have added four doublings, the contribution would be $42+ a person, so considerable juggling would be useful for a few years to smooth it out fairly.

Let's aim for $200 a year for five or ten years for everybody over age 40 or something of that nature. To pay for Medicare coverage, that's amazingly cheap. That's a rough estimate, of course. The overall effect is for the child to wear down his gift from grandpa from birth to age 21, paying $42+ at age 40 to support his own grandchild. He pays for his own care from age 21 to 66. During the transition, a late starter would pay $200 a year for several years after age 40 to make up for his late start, and others would pay the same, but starting later. There are a hundred ways to do this, and the choice would be for the most palatable appearance. We have other, possibly more acceptable, approaches, but this one links well with other goals.

Proposal 22: Congress should enable one voluntary transfer between the Health Savings Accounts of members of the same family, especially grandparents and grandchildren, or one transfer to a general pool for atypical families. Members of the grandparent generation who have no grandchildren may choose one substitute from outside the family, or leave the decision to the fund.Proposal 23: Congress should permit voluntary buy-outs from the Medicare program, which include consideration of returning payroll deductions, and fair accounting for premiums, copayments and benefits already paid for by age groups in transition; but make little effort to encourage buyouts, until prices start to fall.

All in all, the conclusion of this analysis is that targeted programs are probably better for the thirty million people with special needs, so universal one-size-fits-all is probably not a good goal. Privatizing Medicare is a good goal, but we may not be quite ready for it. What's left is to fund the healthcare of children, by mildly overfunding the healthcare of seniors. That ought to end the discussion of this topic, except for demonstrating how you would control the money machine, exposed by the lack of gold or other standards for the currency. It's done by bringing balances to zero once in a while, and it was uncovered by working around the grandparent-grandchild transfer. By studying what's left, we reach the conclusion that fixing the children problem would do the most good for the least cost, and just about everything else has major disadvantages.

Let us then do this much without waiting to see what Obamacare is going to do. If the Federal Reserve's inflation targeting serves the purpose, this may be held in reserve, but the failure of Keynesians to reach 2% inflation when they try to inflate on purpose, should make everyone uneasy about their approach in a currency system which depends on printing money until short-term interest rates rise to 2%. As the man in the audience called out, "Haven't you been to the grocery store, lately?"

That Dratted Third Rail

During the Obamacare uproar, I was giving some speeches, and I can tell you that old folks didn't care a hoot, one way or the other. Obamacare wasn't going to affect their medical care at all, so they had only one passing concern. They were afraid Obamacare would cost so much, it would be necessary to raid Medicare to support the promises. As long as no one brought up that issue, retirees didn't care. But as soon as I tested them on the point, they uncoiled like a spring. Plenty of politicians saw the same phenomenon, and nick-named Medicare insurance reform "the Third Rail of Politics". Just touch it, and you're dead. The mathematics is already so strong, no mathematical argument is going to influence any opinion. Essentially, there's a way to make Medicare almost free, but it doesn't matter. What matters is if politics get ugly, political candidates will say almost anything. Right now, and for some time to come, nobody wants to listen to mathematical arguments. They want to know if a red-mouthed opponent can upset them at the polls, by using reckless attacks. They can, and will, and there isn't much that can be done about it. The consequence is, the easiest argument for using compound interest to pay for health insurance is to privatize Medicare, but it has the most political obstacles to overcome.

Whereas, using the same approach for younger people has difficult math because of the shorter time periods. But it has a much easier time of it politically, because young people often don't have insurance, or need insurance, and so they have very little to lose. Furthermore, the regulations issued for Obamacare were often selected for the purpose of hindering Heath Savings Accounts. Much of the coming battle in Congress will be fought over trenches and fences, seemingly erected for the purpose of making progress difficult. That will be true for more than Health Savings Accounts, but that fact is just another irrelevance.

Here's another unexpected twist which will influence future trends. When Medicare emerged from the sausage factory of legislative construction, the hospital part (Part A) was entirely funded by government subsidy, and therefore is an obvious target for adding revenue, based on the fairness argument. That tends to crowd this heavy expense into the category funded by something else and makes the pressure stronger. By another quirk of legislation, Medicare is a subchapter of the Social Security Act, which is now starting to need revenue. So the mechanism already exists to merge retirement income with Medicare surplus, if we ever get a Medicare surplus. The doctor reimbursement part of the Act (Part B) is what people nominally pay for when they pay their Medicare premiums. Now, add the DRG squeeze into the mixture.

Seeing hospital revenue for inpatients squeezed by the DRG, the hospitals have responded by enlarging their outpatient areas and hiring practicing doctors to join their staff on (somewhat above-market level) salary. Although hospitals pay higher salaries, there can be little doubt they would squeeze those inflated salaries if revenue got squeezed. Meanwhile, Medicare is confronted with a mass movement of doctors from Part B to Part A, and so it raises the premiums in extraordinary jumps, which only affects the premium still more. Unless things are changed, that means there will be less money for Social Security, and the hope of merging the two programs will be greatly injured. Meanwhile, if the hospitals squeeze the salaries, there will be a surge of physician returnees to private practice, ultimately raising Part B premiums, or else lowering physician incomes, leading to a doctor shortage unless reimbursement is raised, and new medical schools founded. Patchwork will be applied. The long-run consequence of single-payer would be to slow the merger of Medicare with Social Security. The latter merger would have some mutual advantages, whereas merging Medicare with private insurance would be an acrimonious take-over of one way of life by the other. What a tangled web we weave.

First Year of Life, and Tort Reform

The problems of paying for the healthcare costs of the first year of life are relatively small financially, but create large unexpected problems throughout healthcare payment design. According to CSS, the first year of life accounts for 3% of total lifetime costs, while all of the childhood up to age 21 only totals 8%. By contrast, the Medicare age group accounts for 50% of costs. But the little tail is wagging the dog.

Without any prior earning capacity, pre-funding the 3% is out of the question unless Congress permits transfers of some sort from others. Legally, that means the parents, but the parents are usually pretty young and impecunious themselves. All manner of matrimonial tangles can occur, but even in the life of a blissful young couple, paying off that heavy cost may take several years to work around. It is hard to believe this issue would not delay the next pregnancy or even sometimes put it out of the question. There is little question younger mothers have a much easier obstetrical time of it than if they wait until they can afford the cost. The whole concept of a "valuable" baby was largely unknown seventy years ago. In my day as an intern, if a lady miscarried, well, just wait a couple of months and have another. The present generation of mothers are aghast at such callous attitudes, but that attitudinal shift is why we once had so many orphanages, and today have so few. The high cost of obstetrics must have something to do with it. We hear it said that women going to work caused a drop in the birth rate, but there is little doubt some of this was the reverse.