1 Volumes

Revolutionary War Era

The shot heard 'round the world.

Montgomery County, Pennsylvania

.

.

|

| Montgomery County Map |

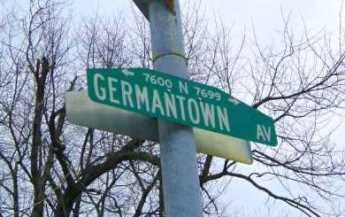

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

|

| Germantown Map |

Chestnut Hill really is a big hill poking up in the middle of Philadelphia, and Germantown Avenue follows an old Indian trail from the Delaware River right up to that hill. The waterfront area of the city has been built and rebuilt to the point where it's now a little hard to say just where Germantown Avenue begins. From a map viewpoint, you might look for a four-way intersection of Frankford Avenue, Delaware Avenue, and Germantown Avenue, underneath the elevated interstate highway of I-95. The present state of demolition and rubble heaps suggests that a Casino might be built there sometime soon, politics and the Mafia permitting.

|

| Fair Hill Cemetery |

Although Germantown Avenue has wandered northwestward from this uncertain beginning for over 300 years, up to the rising slope of the town toward Broad Street, it is now rather difficult to make out anything but industrial slum along its path which could be called historic. There is hardly any structure standing which has a colonial shape, and no Flemish bond brickwork is seen in the tumble-down buildings. When with the relief you finally approach Temple University Medical Center at Broad Street, the Fair Hill cemetery does show some effort at preservation, and a sign says that Lucretia Mott is buried there. But that's about all you could photograph without provoking suspicious stares. Here's the first of four segments of Germantown Ave., and it's a pretty sorry sight.

|

| Chew Mansion |

Crossing Broad Street, the busy intersection suggests 19th Century prosperity in its past, and on the west side of Broad, you can start to see signs of historic houses, either in colonial brickwork or grey fieldstone. The road gets steeper as you go west past Mt. Airy, where it almost brings tears to the eyes to see brave remnants of another time. George Washington lived here for a while, and the Wisters, Allens, and Chews; Grumblethorp and Wyck. The huge stone pile of the Chew Mansion glares at the imposing Upsala mansion, where British and Americans lobbed artillery at each other during the Battle of Germantown. Benjamin Chew the Chief Justice built this house as a summer retreat, to get away from Yellow Fever and such, and started the first migration to the leafy suburbs. His main house was on 3rd Street in Society Hill, next to the Powels and where George Washington stayed. At the peak of the hill in Chestnut Hill, a suburb within the city. Germantown Avenue rather abruptly goes from the relics of Germantown to the charming elegance of Chestnut Hill, but during a recession, it frays a little even there. At the very top is the mansion of the Stroud family, now in the hands of non-profits; across the road in Chestnut Hill Hospital, once the domain of the Vaux family. Then down the hill to Whitemarsh, where the British once tried to make a surprise raid on Washington's army. As you cross the county line into Montgomery County, it's conventional to start calling the Avenue, Germantown Pike. Germantown Pike was in fact created in 1687 by the Provincial government as a cart road from Philadelphia to Plymouth Meeting. Farmers used to pay off their taxes by laboring on the dirt road, at 80 cents a day. Germantown Pike, Ridge Pike, Skippack Pike, Lancaster Pike, and others are a local reminder that Pennsylvania was always the center of turnpike popularity; that's how we thought roads should be paid for. The present governor (Rendell) hopes to sell off some better-paying turnpikes to the Arabs and Orientals, possibly imitating Rockefeller Center by buying them back and reselling them several times by outguessing the business cycle. Parenthetically, the Finance Director of another state at a cocktail party recently snarled that the purpose of privatizing state infrastructure was not to raise revenue, but to provide collateral for more state borrowing. He wasn't at a tea party, but he may soon find himself there.

From a modern perspective, the third segment of the Germantown road runs from Chestnut Hill to Plymouth Meeting, with lovely farmhouses getting swallowed up by intervening, possibly intrusive, exurbia. The township of Plymouth Meeting is a hundred years older than Montgomery County, having been built to be near a natural ford in the Schuylkill River. Norristown, a little downstream, is the first fordable point on the Schuylkill, with Pottstown making a third. Plymouth's colonial character survived a period of industrialization based on local iron and limestone, and has established several prominent schools for the surrounding area. But the construction of a substantial highway bridge attracted a large and busy shopping center. The shopping center looks as though it will eradicate the quaint historical atmosphere more effectively than industrialization ever could.

The fourth and final segment of Germantown Pike starts at the Schuylkill and goes over rolling countryside to its final destination at Perkiomenville, where it joins Ridge Pike at the edge of the Perkiomen Creek. That's an Indian name, originally Pahkehoma. Perkiomenville Tavern claims to be the oldest inn in America, although that honor is contested by another one along the Hudson River near Hyde Park. The WPA during the Great Depression constructed a large park along the Perkiomen Creek for several thousand acres of camping and fishing, so Perkiomenville has several large roadhouse restaurants and antique auctions for bored wives of the fishermen. In the V where Ridge Pike and Germantown Pike come together, a dozen or more colonial houses are tucked away in a town called Evansburg. This formerly Mennonite terminus of Germantown Pike obviously still has a lot of charm potential, and its local inhabitants are very proud of the place. But it's easy to zip past without noticing the area, which includes an 8-arch stone bridge, said shyly to be the oldest in the country. It's hard to know whether you wish more people would visit and appreciate; or whether you are happy that obscurity might permit it to survive another century or so.

|

| Chestnut Hill Hospital |

The name change of the Germantown road from Avenue to Pike is probably not precisely where the turnpike began, but it is now notable for some pretty imposing mansions, standing between the humble and even somewhat dangerous slums along Delaware, and the charmingly humble but well-preserved Mennonite villages, at the other end. It is arresting to consider the two ends, whose houses were built at the same time; only the Mennonites endure. Somewhere just beyond the Chestnut Hill mansions is an invisible line. West of that point, when you say you are going to town, you mean Pottstown. When you say you are going to the City, you mean Reading. And as for Philadelphia, well, you went there once or twice when you were young.

Harriton House

|

| Harriton House |

Three hundred years ago, in 1704, Roland Ellis acquired 700 acres of the Welsh Barony in what is commonly called Philadelphia Main Line and built a palatial house on it. He called his homestead Bryn Mawr, or great hill, after his ancestral home in Wales of the same name, thereby explaining why Bryn Mawr College and Bryn Mawr town have the name but are not notably situated on hills. The town of Bryn Mawr was once called Humphryville. But Bryn Mawr sounded nicer, even though there are plenty of Humphries still around to defend the older designation.

About fifty thousand acres were set aside by William Penn as the Welsh Barony, and there was the willingness to allow it to be self-governing, although that didn't much happens because the inhabitants saw no point in being self-governing. Nevertheless, the term isn't just an ethnic allusion, but has some historic meaning.

In any event, Ellis proved to be an unsuccessful manager of his estate, which rather soon passed into the hands of the Harrison family, who lived on it for about two hundred years until real estate development, and the taxes related thereunto, forced the creation of a complicated arrangement, with the township of Lower Merion owning the property and a non-profit group called the Harriton Association managing it. They have luckily obtained the services of a famous curator, Bruce Gill, who does research, writes papers, and organizes programs for visitors. The neighbors in the area, all living on land that formerly belonged to the Harrisons, are said to constitute the richest neighborhood in America. By building the original farmhouse rather far from the main road (Old Gulph) and remaining surrounded by neighbors who want to have privacy, Harriton House has fewer visitors than it deserves because it is so devilish hard to find.

There was a little local skirmishing during the Revolutionary War, but the main historical significance of the House was that Charles Thomson married a Harrison and lived there all throughout the period of the Revolution and the Articles of Confederation (1774-1789) as the Secretary of the Continental Congress. His little writing desk is, therefore, the most notable piece of furniture at Harriton House since every piece of official paper involved in the whole Revolutionary episode passed through it or over it. Modern organizations would do well to notice that Thomson was not given a vote and was expected to be totally unbiased about Congressional affairs. Even in those days, there must have been cautionary experience with secretaries who tinkered with the minutes for their own preferences. It certainly was entirely fitting that this last steward of the Articles of Confederation was designated to carry the news to George Washington at Mount Vernon, that he had been elected President of the new form of government. No doubt, Washington was pleased but unsurprised to learn of it.

While Harriton House is imposing on the exterior, and was the likely prototype of many characteristic Main Line stone mansions, the inside of the house is quite primitive. In those days it was cheap to build a big house but expensive to heat it. In 1704 surrounded by a continent of a forest, firewood may not have seemed a problem, but it quickly posed a transportation problem, and later houses tended to shrink in size. In any event, the interior of the house seems strangely bleak and bare, quite in keeping with the early Quaker principle of building a structure "without paint, or other adornments". Bruce Gill spent quite a lot of time and effort to determine that the random-width flooring had never received any shellac, varnish or wax. Those are beautiful floors, but the "finish" is just three hundred years of oxidized dirt.

The original Bryn Mawr, now called Harriton House, is well worth a visit. If you can find it; GPS is the modern solution.

Radioactive River Bend

|

| Gold Cert |

A mile or two south of Pottstown, the Schuylkill River encounters a rocky ridge several hundred feet high and makes a bend around it. The first Treasurer of the United States, Michael Hillegas, built a colonial mansion on the point of the bend, and it has been lovingly restored and preserved by a noted Philadelphia surgeon and his wife. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury under the Constitution, has his picture on the modern version of a ten-dollar bill. So it is appropriate that Hillegas, the first Treasurer under the Articles of Confederation, had his picture on many versions of a ten-dollar gold note, back in the days when the American dollar was as good as gold. River Bend Farm is not only colonial, charming and maintained in mint condition, but it is also tucked away between the bend in the river and the high ridge to one side, giving it seclusion and privacy.

A high ridge near a river is unfortunately also an ideal place to build a nuclear power plant, and that's where the Limerick plant now looms up, glowing at night, occasionally making faint humming noises. There's a limited-access highway from Philadelphia to Reading which swoops up the valley, and the two high cooling towers of Limerick dominate the landscape for twenty miles. Because of the river bend, you aim straight for those towers for a long time before you swerve off, and the view is much like that from the bomber cockpit of the final scene in the movie "Dr. Strangelove". It gets your attention harmlessly, but it's hard to ignore. In spite of all sorts of official reassurance, everybody knows about Three-Mile Island, and Chernobyl, but few people emphasize there has never been a single injury from an American nuclear plant.

So, in 1981, everybody was ready to go into orbit when a worker named Watrus showed up for work at the nuclear plant and set off all manner of clanging alarms from radioactivity detectors. Panic and pandemonium for weeks, until a remarkable phenomenon was discovered. Watrus wasn't radioactive from the nuclear plant at all, but from having his work clothes laundered in his own basement. It slowly developed that radon gas seeps through the ground in many places in the United States, particularly over rocky ground. The gas then rises into the basement of houses and gets trapped. The more tightly the storm windows are applied and the more carefully sealed the seams of the house, the harder it is for the radon to escape. The Pennsylvania Dutchmen who live around Limerick are a little skeptical of this story and are not inclined to live any closer to the power plant that they have to. They are just as much in favor of oil self-sufficiency as anyone else, but still, no one likes being close to it.

The big winners from all this confusion are the people with radiation detectors, who go around the country testing people's basements for radon, for a fee. But unless you are willing to go live on the Sahara Desert, it isn't easy to see where you are going to go to avoid radon.

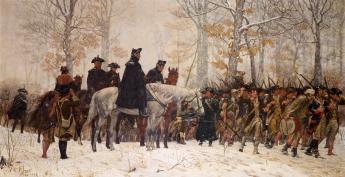

La Fayette, We Are Here

|

| Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette |

It will be recalled that La Fayette was 19 years old at Valley Forge, spoke no English, had no previous military experience. He nevertheless demanded, and got, a commission as Major General on the prudent condition that he have no troops under his command, at least for a while. Washington had been strongly reminded by various people that this young Frenchman was one of the richest men in France, a personal friend of the Queen, and thus critical to the project of enlisting French assistance in the war. Under the circumstances, it was shrewd to send him on the project of enlisting Indian allies among the Iroquois, since many tribes, particularly the Oneida, spoke French and held their former allies in the French and Indian War in great esteem. The chief of the Oneida Wolf clan (Honyere Tiwahenekarogwen) was visiting General Philip Schuyler in Albany at about the time LaFayette showed up on his mission to get some help for Valley Forge. General Horatio Gates was busy at the time rallying a colonist army to defend against the British under Burgoyne, coming down from Quebec, eventually to collide at the Battle of Saratoga.

Earlier in the war, Honyere's Oneida tribe had tangled with their fellow Iroquois under the leadership of Joseph Brandt (the Dartmouth graduate who was both biblical scholar and commander of several frontier massacres); the Oneida had many new scores to settle with the English-speaking Iroquois tribes. Honyere made the not unreasonable request that before his warriors went off to war, his new American allies would please build a fortification to protect his women and children from Brandt's Mohawks. LaFayette readily put up the money for this project, quickly becoming the Great French Father of the Oneidas. After some scouting and patrolling for Gates, Honyere and about fifty of his braves followed LaFayette to Valley Forge, where they soon made a nuisance of themselves to the Great White Father George Washington. Finally, word of the official French alliance with the colonists reached London, Howe was replaced by Clinton, and the British began to withdraw from their isolated position at Philadelphia.

It was thus that the jubilant rebels at Valley Forge learned that the fortunes of war had turned in their favor, and the French alliance was the source of it. With the British making preparation to abandon Philadelphia, it seemed a safe thing for Washington to give LaFayette command of two thousand troops, including the fifty Oneida Indians, and post them to Barren Hill (now LaFayette Hill), along Ridge Pike near Plymouth Meeting. Washington gave the strictest orders that they were to take no chances with anything, and particularly were to remain mobile, moving camp every day. This was not exactly what the richest man in France was anticipating, and wouldn't make a very saucy story to tell Marie Antoinette about. So, he promptly set about fortifying Barren Hill. Local Tory spies quickly spread this news to General Clinton, who promptly led eight thousand redcoats up the Ridge Pike to capture the bloody Frog. Clinton's plan was good; a detachment went around LaFayette in the woods and came back down Ridge Pike from the other direction, driving the Americans down the Pike into the open arms of the main body of British troops, coming up Ridge Pike. From this point onward, two entirely different stories have been told.

The more widely-held account has LaFayette climbing the steeple of the local church and noticing that there was an escape path, leading down the hill to the Schuylkill River at Matson's Ford. The Indian scouts were sent forward to hold off the British while the troops made their escape. Clinton sent a cavalry charge of Dragoons forward, yelling and waving their sabers, generally making a terrifying spectacle. The Indian scouts, as was their custom, were lying in the brush shoulder to shoulder, and at command by Honyere rose from the ground to let out a resounding chorus of war whoops. The Indians had never seen a cavalry charge, the Dragoons had never heard a war whoop, so both sides fled the battlefield without doing much damage. Meanwhile, LaFayette and his troops escaped to safety on the far side of the Schuylkill.

Other accounts of this episode relate that when Washington heard of it he remarked sourly that either they were pretty lucky, or else the enemy was pretty sluggish. In any event, a few soldiers were killed on both sides, the Americans crossing the River were described as "kegs bobbing on the pond", and it does seem the British army mostly just watched them do it. In the confusion, of course, everyone involved was fearful of being surrounded by unseen troops, and the British may well have worried the whole thing was a trap.

The saddest postscript to the Battle of Barren Hill is the fate of the Indians. After the war was over in 1783, the colonists busied themselves with taking over Indian land. Honyere pitifully petitioned the New York legislature for some consideration of his tribe's wartime service. They ignored him.

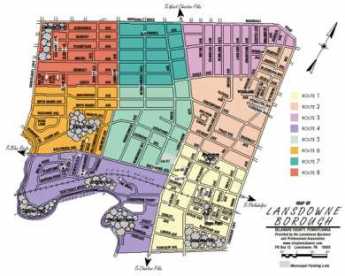

Lansdowne

|

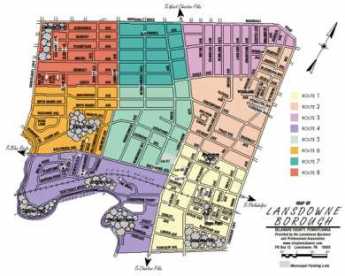

| Lansdowne Map |

The Granville, or Lansdowne, the family had so many members important in English history, that the Lansdowne name adorns countless schools, boroughs, colleges, museums and other monuments around the former British empire. It would require undue effort to sort out just why each memorial is named after just which member of the family. In the Philadelphia region, Lansdowne is the name of a small borough in Delaware County,

|

| Lansdale |

often annoyingly confused with Lansdale, a small borough in Montgomery County. However, it really seems more appropriate to focus reverence on the Lansdowne mansion, which from 1773 to 1795 was the home in now Fairmount Park of the last colonial Governor. That would have been John Penn, who was one of several Penns who still shared the Proprietorship until 1789, and who shared in the miserly payment which the Legislature of the new Commonwealth made as compensation for expropriating twenty-five million acres of their property. The French Revolution was going on at that time, so there were probably some patriots who would scoff that John Penn was lucky not to be guillotined.

The Penn family could see the Revolution coming, and like everyone else was uncertain who would win. Real decision-making for the Proprietorship rested with Thomas Penn in London, a close friend of the King and his ministers. The strategy employed in this difficult situation was to surrender the right to govern the colony conferred by its original charter and to become mere real estate owners with John their local representative pledging local allegiance. That might have worked for a while, until General Howe's troops captured Philadelphia. Soldiers were dispatched to Lansdowne to tell John Penn he was under detention, to reduce his potential utility to the occupying army.

|

| Horticultural Hall |

As matters eventually worked out, some of the Penn descendants remained fairly wealthy after the Revolution, especially those whose wives had inherited substantial assets from other sources. But some were severely impoverished. The stately Georgian mansion burned down in 1854, and the site was then occupied by the Horticultural Hall of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Perhaps because of misplaced patriotic fervor, it is now difficult to find a picture of Lansdowne.

The elegance of the place, on 140 acres, is suggested by the fact that William Bingham the richest man in America at the time, apparently acquired it from James Greenleaf the partner of Robert Morris, and the nephew by marriage of John Penn, who acquired it from Penn's estate but probably had to give it up in the financial disasters of Morris and his firm. Lansdowne was still a grand manner when it was briefly acquired by Joseph Bonaparte, the former King of Spain. In view of the fact that Bingham had provided President Jefferson with the gold to finance the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon Bonaparte, and earlier had practically forced the Congress to call off an impending war with France, there was likely a connection here.

And to some extent, the ill-treatment which John Penn received from the Pennsylvania legislature (roughly fifteen cents an acre) in the Divestment Act of 1779 can possibly be traced to the unrelenting hatred by Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania's icon. History does not tell us what made these two former friends fall out in 1754, sufficient to make Franklin willing to spend years in London trying to get the colony away from the Penns. The feeling was surely mutual. When John Penn was offered the patronship of the American Philosophical Society, he declined, just because Franklin was its president. In retrospect, that sounds unwise.

Potts

Rebecca Potts used to say there were three towns in Pennsylvania named after her family -- Pottstown, Pottsville,

|

| Pottsville biennial |

and Chambersburg. Becky never designed to explain whether Chambersburg was just a joke or whether her very extensive family really had connections in Chambersburg. It's possible either way; there were certainly Potts inValley Forge where Washington's Headquarters, which everyone visits, had been home to Isaac Potts, the third generation of Dutchmen named Potts to live there. Isaac ran a grist mill, the others mostly were ironmasters. The family seat in Pottstown was named Pottsgrove, still open for visitors. Holland Dutch they may have been, but Pottsgrove architecture is definitely of the Welsh style.

|

| Pottsville Coal |

Pottsville, much further up in the anthracite region, became notable through the novels of John O'Hara, a native son. For a whole generation, just about everybody in Pottsville was uneasy that O'Hara would confirm just who certain characters in his moderately raunchy novels represented in real life. Pottsville's main business for a century was extracting coal for the Girard Estate, which had its coal-mining headquarters in the town, based on Stephen Girard's shrewd purchase of nearly all of Schuylkill County.

The broad sweeping view from the interstate highway going north from Valley Forge makes it easy to see how Pottstown was created by the upheaval of a mountain ridge, which split open to let the Schuylkill River wind through. Pottstown is a water gap. The huge cooling towers of The Limerick nuclear power plant dominate one side of the river cliff and can be seen for miles. The cliff on the other side of the river, behind which hides the town of Pottstown, used to shelter the Wright aircraft factory, much of which was underground. That gave it a railroad (The Reading RR) and ready access to the river, plus privacy from the land side. Down to the right a mile is the Pottstown Hospital, on the edge of town, quite near the campus of the famous Hill School, fierce competitors of the Lawrenceville School in sports. Just about everything in this area is on top of some kind of hill.

Just back of the hospital, seemingly on the grounds of it, rises a peculiar steel tower, which the local workmen report is a sending station for cellular telephones. However, one of the doctors of the hospital relates a somewhat different history. He says he was once called on a medical emergency, told to ring the elevator at the little house beside the steel antenna, and travel down, down, into secret depths. He found himself in the headquarters of the Northeastern Air Defense Command, which was certainly hidden in an ideal place if the story has any truth to it. Unfortunately, that story-teller was a famous cocktail-party raconteur whose wild tales were never to be taken completely seriously. For many years, the hospital on a cliff was surrounded by corn fields, and it is certainly true you could look out the windows at a sea of corn, never suspecting you were very close to a railroad and a river, quite possibly right over an underground aircraft factory. Someday it may be possible to find out the truth of these tales of the Dutch country.

During the American Revolution, the British blockaded the coast and landed troops on the main coastal highways. The Americans responded in a quite natural way by building an inland north-south forest trail, sort of on the order of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Pottstown was one natural stop on this trail, which tended to intersect with many roads coming up along the banks of the coastal rivers. In one very famous episode, wagon loads of Philadelphia Quakers were arrested and taken up the Schuylkill to Pottstown, then south to internment at Winchester, Virginia. They weren't exactly Tories, but they certainly were not sympathetic to revolutions. One of the most famous of these semi-prisoners was Israel Pemberton, one of the leaders of the Quaker colony. He later reported he was treated well, but onlookers in Pottstown described him as being thoroughly abused.

Pottstown had a century of prosperity during the industrial age, then declined and decayed. In recent years. The interstate highway has brought a migration of exurbanites whose taste in architecture tends toward McMansions. Let's hope they can acquire a dose of local history, starting a new historical revival of a town with great potential, considerable past glory, and a wonderful natural setting.

Quilts, Patchwork Style

Although quilting can be found in the tombs of ancient Egypt, American farm women are correct that they invented an art form.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

In the days when transport was primitive, art forms were invented in many places at once, mostly responding to new materials and new technologies. It's irrelevant to the genius of creation, for archivists to pounce on evidence that an art form surfaced a decade or two earlier in one place than another. Creative art could easily have been -- and often was -- invented by five or six people in different regions, each with a just claim to inventing without copying. In the case of quilts, there is a semantic wrinkle, too. If you define quilting as the process of anchoring three layers of cloth together with stitches, then quilts have been found in ruins of ancient China and ancient Egypt. The underlying principle was that three layers of cloth were warmer and stronger than single sheets of cloth or animal skins, so quilting was used for shoes, pants, jackets, and underneath suits of armor. Mary Queen of Scots spent a lot of time in confinement, and examples still survive of tapestries she made with the quilting process. None of this is what American farm women mean when they say that "quilts" are an American invention, and a new art form.

|

| Quilt, Patchwork Style |

What they mean is patchwork-quilting of bedspreads or counterpanes. To make that specific kind of quilt, you pretty much have to wait for the industrial revolution to provide decorated cotton cloth, then for it to become cheap enough to be used as sacks for flour. That attracts frugal farm wives salvaging material for dresses and shirts, and later re-salvaging pieces of it for patches. Somewhere the idea caught on that decoration was needed for the tops of beds; if these ornaments were usable for extra warmth it was even better. And so, we got patchwork counterpane quilts, incorporating different colored patches into designs. They start appearing around 1750 but gained real popularity around 1830. Since no one was keeping records, it's hard to know if the common diamond design was an outgrowth of the Scotch-Irish street "diamond", or an outgrowth of the hex signs which are commonly believed to have originated in the monastery in Germantown. The path of westward migration would have carried such traditions to the rest of the country, so this analysis has some plausibility. However, the ideas are so simple it would surely be impossible to trace them. What is so unique about this folk art is that the design can be oriented around a piece of a favorite grandparent's shirt or dress, evoking that person's presence and personality in a manner largely incomprehensible to anyone except the immediate family. This intimate quality is easily lost, even in third and later generations of the family, although family traditions can be maintained in the designs and by hearsay.

There may be other traditions of folk art evoking a particular individual who is unrecognizable to outsiders. They might admire features of the design but have no way of knowing the personality of the person celebrated, or making associations with the piece of cloth. But this quilt art becomes established as a family heirloom as almost nothing else could be. Its sweetness is oblivious to the fashion police who contribute a rather aggressive undertone to so much of the art world. For example, in the period between the first World War and the Korean War, it was just about impossible to have a non-modernist painting accepted for a juried show. The same juries who enforced such competitive dictates seemed to forget they denounced the "conservative" academics who excluded impressionist painting a century earlier. During the modernist period, disk jockeys and band leaders likewise serially enforced the various fashions of jazz music; classical music was totally banished. Book reviewers, now a dwindling race, similarly laid down standards of obedience for authors and playwrights on behalf of a style now commonly praised as "liberal". Publishers and producers defied such dictates at their peril, and now must reorient to the coming new standard, called post-modernism.

By contrast, the isolated troubadours of home quilting artistry continue to create as they please, primarily speaking to their families and selling a few less treasured products -- to uncomprehending strangers.

Albert C. Barnes, M.D.

A private investor has the general goal of accumulating enough wealth so, come what may, there will be a little left when he dies. If he has dependents or heirs, he needs somewhat more. Either way, he is not planning for perpetuity or thinking in astronomical time periods. Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) had to switch his investment goals, in the 1920s, from investing for a comfortable retirement to investing for a perpetual art foundation. Perpetual.

|

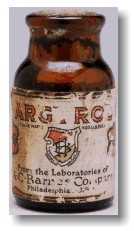

| A bottle of Argyrol |

Having graduated from medical school (University of Pennsylvania) in 1902, and then writing a doctoral thesis in chemistry and pharmacology at the Universities of Berlin and Heidelberg, Barnes invented a patent medicine that quickly made him rich. Argyrol was a mildly effective silver-containing antiseptic with the unfortunate tendency to turn its users permanently slate-gray. The advent of antibiotics has since made Argyrol almost sound like quackery, but it was effective enough at the time to require factories in America, Europe, and Australia, and Barnes became immensely rich with it. The American Medical Association strongly disapproves of physicians who patent remedies, so Barnes was never held in high regard by his colleagues; but it could well be argued that he had as much training as a chemist as a physician, and spent his entire professional life as a chemist, manufacturer, and investor.

|

| The Barnes Gallery |

Barnes was eccentric, all right, but on Wall Street, the saying goes, "What everyone knows, isn't worth knowing." Guided by that principle, in 1929 he sold his company at the very peak of market euphoria, getting out of common stocks at the top of the market. It is small wonder that he soon instructed his Foundation to invest its endowment entirely in bonds. During the 1930s, commodities were extremely cheap because no one had any money. Barnes, of course, had a potful of money and bought hundreds, even thousands, of artworks very cheaply. He also bought 137 acres of Chester County, PA, real estate, and a 12-acre arboretum in Merion Township on the Main Line. Although he is famous for acquiring hundreds of French Impressionist paintings with the advice of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, he also bought great quantities of Greek and Roman classical art, African art, and the art of the Pennsylvania German community. He picked up a notable collection of metallic art objects. Most of these "losers" are down in the basement because he had so many Renoirs, Matisse, and Picasso (some of them may be worth $200 million apiece) that the upstairs galleries were pretty well stuffed with them. Viewed from the perspective of an investor with a goal of perpetuity, of course, the things in the basement just happen to be temporarily out of fashion, just like those bonds in the portfolio.

|

| A view inside the Barnes gallery |

Since the Foundation is currently strapped for ready cash, Judge Stanley Ott of the Montgomery County Orphans Court is now being urged to allow the Foundation to break Barnes' will in some way or other. Move the museum to downtown Philadelphia where it can attract more paying visitors. Sell some of that land. Sell some of those paintings in the cellar. Fire some of those employees. But all of these suggestions are short-term solutions, which may injure the long term. Everybody has an idea of what Barnes the rich eccentric would have done if he were alive to do it, but I suspect he would have rejected the whole lot. Barnes the shrewd investor would have taken the most expensive painting off the wall, and sold it to the highest bidder. Buy low, sell high, and the niceties of non-profit professionals are damned. Barnes wasn't in love with one single painting, or one particular school of painterly interpretation, he was in love with Art.

Investment theory has improved in the past fifty years; there have even been some Nobel prizes awarded for new insights. But it still isn't possible to put an investment portfolio on autopilot for perpetuity. Every museum, university, and the foundation has the same problem, with the result that the landscape is littered with the bones of perpetual organizations destroyed by following a fixed formula. With the singular success that Barnes displayed, it isn't surprising that he went a little too far with instructing his successor trustees in what to invest in. Never sell the paintings or the real estate, avoid the common stock, were ideas that worked brilliantly, and may even work most of the time. But sooner or later, the institution will be endangered by following them too literally. Somebody has to have some flexibility. But there is something else that is inevitable, too. Sooner or later, whether it takes fifty years or five hundred years, sooner or later someone will be given the responsibility and the necessary flexibility -- but will try to run off with the boodle, for himself. The balance between necessary prudence and necessary flexibility is impossible to maintain forever, and the Judge will surely have a hard time deciding what Barnes would have decided.

The Barnes Foundation: Comments on the Economics of Art (2)

In 1951, Albert C. Barnes' legacy included Jerome's Epistle to Paulinus from the Gutenberg Bible education centered on a notable collection of illustrative artworks, housed in a museum of his own general design for the purpose. He left a multi-million dollar endowment to support his rather detailed and, in the opinion of many, somewhat eccentric intentions. It was his money, however, so his word was final. The institution was fairly mature, having previously been in operation under his direct control for twenty-five years.

Since the Foundation trustees are now before the Orphans Court pleading for permission to modify Dr. Barnes' instructions in order to avoid financial collapse, skepticism is inevitable. Obviously, the successor trustees must explain their expenses. But quite a plausible case can be made that the true cause of this disaster is inherent in the huge windfall growth in value of the paintings. In short, growth in value of the fine art may have outstripped the growth of the resources set aside for maintenance.

|

| Johann Gutenberg, creator of mass produced books, died in poverty |

Let's make a benchmark of the Gutenberg Bible, where incomplete copies are currently selling for $100,000 a page and complete copies are estimated to be worth $100 million apiece. Dealers maintain the Gutenberg is increasing in value at 20% a year, but growth seems closer to 9% a year if you go back to 1951. What's really relevant here is the growth in cost to ensure, protect, dehumidify, display and make it available to scholars, if not the public. It seems safe to guess these maintenance costs have grown more rapidly than the investment growth of the endowment, which is surely closer to 4% than 20%. The imbalance is even greater if you remember that some investment income is spent every year, while the worth of the fine art just grows and grows. Regardless of the true numbers, if the cost of maintaining the art does grow even slightly faster than the endowment, the dilemma the Barnes is now facing will eventually face any museum. New sources of revenue, either from the government or from public admissions, eventually becomes necessary if the priceless art remains on display. It is displaying these things that cost money; burying them under an Aztec mound or a German salt mine shelters them from the problem. In the case of Alfred Barnes, it is not completely certain that he wanted them displayed.

There is also the issue of quirky fluctuations in the market for fine art. The 22 known perfect copies of Gutenberg, Bibles have been around for almost five hundred years, and it is safe to say their value is enduring. The 180 paintings by Renoir now owned by the Barnes may prove to be Gutenberg Bibles or they may prove to be a passing fad, but it is pretty hard to believe that one of them will always be worth two Gutenbergs. Since there is a pretty fair chance that we are currently seeing a value bubble in French Impressionist painting, it is questionably prudent to shipwreck the whole Barnes Foundation, the School, or Albert C. Barnes basic intent, by resisting the sale of even one of the more overpriced examples in the collection at the top of the market.

That's one side of it. Another consideration is that Barnes himself did considerable merger negotiation with other museums, and may have been unexpectedly killed in an auto accident before he turned over all his cards in that particular poker game. It's asking a lot of the poor judge to overturn the clear and largely unmistakable language of Barnes will in favor of theories about what Barnes was really really thinking when he wrote it. If the judge is feeling adventurous, it's probably more satisfying to all parties if he sets forth a new legal doctrine, reflecting the inevitable disparity between the cost of displaying fine art to the public, and providing a perpetual endowment to do so.

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

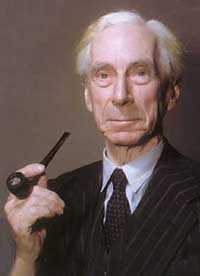

|

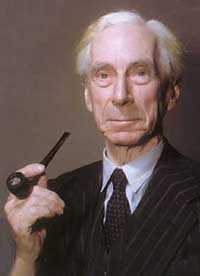

| Russell |

In 1940, the Barnes Foundation disturbed its Philadelphia's Main Line neighborhood in a way that had nothing to do with art. Dr. Barnes was still alive and running the place at that time so there can be no question about the testamentary intentions of the donor. He hired Bertrand Russell for a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Foundation, under highly lurid circumstances. By doing so, he put his thumb in the eye of religions generally but especially the Roman Catholic Church, into the eye of the Main Line neighborhood that prized its privacy, and into the eye of the judiciary, although the judiciary found a way to get back at him.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Under the circumstances, hiring anyone at all would have been socially defiant, but Barnes went out of his way to offer a position to a man who was already internationally famous for sticking his own thumb in everybody's eye.

Lord Bertrand Russell was the third Earl, the son of a Viscount and the grandson of a British prime minister. He had such a brilliant mathematical mind that no less an observer than Alfred North Whitehead regarded him as the smartest man he ever met. He burned up the academic track at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society at an early age. There was absolutely no one in the academic world who could look down on him, particularly no one in any American community college. His association with Haverford Quakers was established by marrying Alys Pearsall Smith, a rich thee-and-thou Quakeress then living in England, whose brother was the famous author Logan Pearsall Smith. Many early letters of Bertrand Russell contain instances of what the Quakers call "plain" speech.

If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

By the time of World War I, this odd mixture of Quaker pacifism and English aristocratic arrogance seems to have unhinged Russell from social moorings, and he began a lifelong career of defiance mixed with a rapier wit that made just about everybody his enemy. He went to jail for pacifism, got divorced three or four times, openly slept with the wives of famous people like T.S. Eliot, and proclaimed that monogamy was not a natural state for anybody. He wrote ninety books, and his denunciation of religion was sweeping. All religious ideas were, in his view, not only false but harmful. Accordingly, everybody in polite society kicked him out, and although he was entitled to a seat in the House of Lords, by 1939 he was nearly impoverished. In desperation, he went to (ugh) America to seek his fortune. He didn't last at the University of Chicago, and even California eased him out. Finally, he was reduced, if you can imagine, to accepting an offer to teach Philosophy at the City College of New York. That proved to be totally unacceptable to Bishop Manning, who led a public outcry against using public funds to support such a radical, known to have held long conversations with Lenin. When a CCNY student was induced to file suit along those lines, an especially hard-nosed judge overturned the College appointment, with the rather gratuitous declaration that Russell's appointment would establish a Chair of Indecency. At that point, Albert Barnes stepped in and offered Russell a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia's main line.

|

| Bertrand Russell in 1960s regalia. |

Bertrand Russell the bomb-thrower accepted the offer and came down to that quiet little lane where the neighbors object to the traffic coming to look at pictures. The five-year contract only lasted three years, when even Barnes got fed up, and summarily dismissed him. The circumstances have not been extensively documented, but they were sufficient to enable Russell to win a lawsuit for a redress of grievances. During that three year period on the Main Line, he had produced a book called History of Western Philosophy, which became a best seller and permanently relieved his financial difficulties, and was the basis for his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent the rest of his ninety-odd years leading demonstrations against the atom bomb, the Vietnam War, monogamy, religion and so on. There are those who regard Bertrand Russell as the role model for the whole Sixties generation, and, unfairly, the 2004 Democrat candidate for President. However, all that may be, his activity at the Barnes Foundation undoubtedly was a factor in the firm but the unspoken tradition of the Merion Township neighbors that they wanted to get that Art Gallery out of here.

Greenhouses

|

There are lots of mundane activities involved in having a prize show garden, like compost heaps, cold frames, mud rooms, and the like, which competitive show-gardeners never think of talking about, let alone putting on display. However, someone who feels very competitive about the garden usually lets that competitiveness spill over into the greenhouse. Most working greenhouses are muddy and disreputable-looking. When you see a big greenhouse with a spotless floor, however, you know you are learning something about the owner. When tidiness extends to spotless tools and well-sharpened pencils, there's a message. This greenhouse is not merely a tool shed, it's part of the display.

Let's talk about three outstanding greenhouses in the Philadelphia region which are adjuncts to three outstanding horticultural competitors. To spare the feelings of all concerned, the names of the owners will not be mentioned. In one case, the plants are preponderantly indoor plants, a second one is preponderantly filled with outdoor plants, and the third is full of rarities.

The greenhouse full of indoor plants reflects an owner who primarily competes in flower shows in that type of plant, it is true. But this lady obviously brings the flowers to a peak of perfection and then shifts them into the house. The result is a dining area with twenty-five potted flowers scattered tastefully around, dressing up the house. One presumes the flower pots go back to the greenhouse when they start to wilt a little, and probably an effort is made to have plants which flower at different seasons of the year. Back out in the greenhouse, there are dozens of blue ribbons arranged within picture frames to produce pleasing arrangements in themselves. Although this is a famous horticulturalist of long standing, the blue ribbons on display are only awards from fairly recent shows.

|

The second greenhouse to be mentioned is primarily devoted to outdoor plants, being bred and hybridized in controlled circumstances. The owner has created a garden in the interior of a suburban block on the Main Line, and although the houses are all part of the estate, the effect is one of the certain types of plantings in several backyards, a set of sculpted topiaries in one, a formal arrangement of boxwood designs in another, annuals in another. Although the rotation of plantings back and forth from the greenhouse is here probably more of a one-way trip, essentially the greenhouse is serving the same function as the one servicing the indoor display, a place to nurture plantings which are not quite ready for prime time.

|

And the third greenhouse is primarily run by a husband and wife team of horticultural competitors. The other two gardens look as though they employed a dozen or so gardeners, while this one looks like it supports a two-person hobby. It contains a most unusual fern with its own nickname, and dozens of other display specimens of rare and unusual plants to compete in specialty shows of particular varieties. This greenhouse is just as spotless as the ones with much larger staff to do the cleaning, but it seems to have a wider variety of gardener conveniences to lighten the load and increase productivity. One quickly senses that the husband of the team pores over greenhouse catalogs and quickly adopts labor-saving devices. Space is at a premium in this greenhouse, and one guesses its results as much from a need to conserve steps as to conserve space. The effect faintly starts to resemble the jam-packed cockpit of a space-ship.

One technology advance seems to be so superior they all have it. The exterior surface of the greenhouses is not made of glass, but of polycarbonate plastic, sometimes known as "bullet-proof glass". Greenhouses seem a safe enough use for polycarbonate, although widespread use in disposable plastic water bottles seems a more questionable direction for environmental enthusiasm. This transparent material admits the light of a much wider wavelength, particularly ultra-violet, and no doubt greatly extends the season and the effectiveness of indoor nurture. From the photographer's point of view, the resulting pictures are far more pleasing, with diffused light and greater color brilliance. Thus, science has finally achieved for the Philadelphia region the same striking color of light that was so attractive to French Impressionists in southern France, and to vacationers in Hawaii.

The other thing this plastic invention has done has been to increase the general attractiveness of greenhouses. Until rather recently, it was the custom to paint white-wash on the glass and let it slowly weather away as increased sunlight is needed for the plants. Thus, greenhouses once almost always looked shabby and disreputable; not a place you would want seeing by visitors. But nowadays, you just keep them spic and span. And hold a cocktail party there.

REFERENCES

| Standardized Plant Names: American Joint Committee on Horticultural, Frederick Law Olmsted | Google Books |

A Woman's Work

|

| Feminism |

Whatever the gains and losses of the Industrial Revolution, reproductive need endures. Feminists who proclaim the advice to their sisters, "Have a baby; just don't have two." ignore some pretty simple arithmetic about population growth. What's perhaps worse, they fail to notice conflict with the goal of marrying rich. Rich men can afford a lot of things, but most of them can't afford a working wife. There's a fantasy in soap opera about meeting a fabulously rich man, one who owns motorboats and horses. How glamorous to be swept up by such a paragon; after all, every American hope to get rich.

|

| Big House |

, In fact, it takes training to run a big house, organize big parties, cope with artisans and servants, facilitate the complicated diplomacy of business and political affairs. A rich man expects his wife to run a big establishment, facilitate a complicated social life with those horses, sailboats and extensive travel. And she better maintains her personal glamor, too, because there are lots of younger women who toy with the idea of grabbing him in a weak moment. So even a fun time at the dress shops and hairdressers is obligatory. A man in an exalted position can't afford to have a wife who is employed in some dumb profession; the money she earns is a nuisance.

|

| Finishing School |

So that brings us to colleges and Quakers. A handful of elite women's colleges once tried to accommodate the finishing school with career preparation for blue-stocking women. The student could choose which path to follow but until recently finishing school was predominant, and comparatively few chose to be spinsters. Bryn Mawr College quickly grew to be the most prestigious college in the Philadelphia area, since both the finishing school and the bluestocking career had the needs of the upper class in mind. Quakers don't admit to an upper class but look at their colleges. Haverford was for Quaker males, Bryn Mawr for Quaker women, and Swarthmore for Quakers who fancied co-education. It was a nice arrangement, with Quaker students almost always in the minority, the rest either upper-class (read Katherine Hepburn) or brilliant scholarship students. Bryn Mawr was a little sniffy about the farm-boys at Haverford and the engineering nerds at Swarthmore. Much of that was an adolescent pose, but it created quite a rearrangement when Haverford went co-ed.

|

| Haverford College |

Almost overnight, women college applicants declared a preference for going to Haverford if there was a choice. Within a few years, Haverford students became 57% female, and Bryn Mawr suffered a decline in average aptitude scores. Why ever would girls prefer Haverford to Bryn Mawr? Indeed, if Haverford was headed in the direction of an all-female student body, Bryn Mawr would seem to be the better woman's college to pick. Somewhere buried in this adolescent stampede is probably some television-inspired confusion between the life of a suburban housewife and the life of a rich man's wife, but there certainly is a big difference in attitude about two-career families. On the other hand, there are lots more opportunities for the upper middle class than the lower upper class, both in the number of available mates and in the fall-back opportunity to try to make it as a career woman. Rich men are no longer invariably upper class, nudged by their chums to be wary of career girls. Anyway, college freshmen are pretty malleable; Haverford is a little safer bet if you aren't entirely sure of yourself.

Main Line School Night

|

| Radnor |

There's a lot to learn from the Main Line School Night, and it isn't all taught in the classroom. The basic idea is life-long learning, going to school because it's fun. The idea started five or six decades ago in the Radnor, PA high school, that a lot of educated people wanted to become still more educated in topics of their own selection. No tests, please, and forget about academic credits; most of the students already have an excess of them. Forget about improving your income with advanced degrees; since this is Main Line Philadelphia, quite a few of the students already have all the income they could ever want. As related by the very low-key president of MLSN, David Hastings, the idea was an almost instant success. There were 1200 students enrolled for the second semester. They outgrew the original high school, and now teach courses in seven schools among 40 locations, to 14,000 students a year. There are 400 teachers in any given year, and the tuition charged is aimed at breaking even on the overhead. The academic world is inclined to say the courses lack rigor, by which is partly meant that if the students don't like the course, they walk out. Volleyball, yoga, and nutrition certainly do have a California sound, but computers, foreign languages, and science can be as difficult as you want to make them. If you get serious about contract bridge, you soon learn that isn't a simple child's game. Courses in wine tasting are given in the local senior citizens' retirement communities, but mostly not to the residents. It's not welcome to give that sort of course in a high school. To some extent, this continuing education is an exclusive social occasion, but then so is a course in diplomatic history at Princeton. Mr. Hastings tells of a group of sixteen ladies in a bridge course who have been coming for years, and have learned to close the course rolls by all sending in their checks on the day of registration. This is, after all, the Main Line where exclusionary techniques once learned are hard to forget. There are clouds on the horizon. In the past three years, enrollment has leveled off and declined a little. Almost no major corporation continues to be successful for more than seventy-five years, and many of the people running Main Line School Night are drawn from the Executive Service Corps. In retrospect, for example, the owners and editors of the Saturday Evening Post should have sold out and closed down, as soon as they learned the first million television sets had been sold. Perhaps the decline of enrollment of Main Line School Night reflects the advent of the Internet, or the cell phone, or some other new technological competitor. Or maybe the venture just got too big and successful to maintain its original format; perhaps it's outgrowing its blood supply. But anyway, they have 14,000 students and can be proud to be in a resting phase, when the rest of the city, or state, or country, hasn't even tried to get started on such a project.

Mind Your Manners

|

| Hoeffel |

In 1948 I was an intern at the old Pennsylvania Hospital, assigned for a while to the accident room. One of the accident-room duties of an intern is to sew up cuts and lacerations that arrive unexpectedly, but some lacerations can be out of your pay-grade and you have to call for help. On the evening in question, the victim had been so thoroughly slashed up that I had to call the chief surgical resident, Dr. Joseph Hoeffel. Hoeffel was big, tall, loud and self-assured, and swept majestically into the accident room with a little fellow trailing him. This follower seemed less than four feet tall but very quick and shifty. He didn't walk so much as he scuttled. Hoeffel bellowed, "Get out here!" and the gnome vanished.

While Joe was examining the laceration problem, the little fellow slipped through a different door to see what was going on. Most of us had the impression this guy might well be the one who inflicted the cuts, but in any event, he didn't belong where he was. "I told you to get out of here, and stay out," bellowed our surgeon. Again the scuttler scuttled away, while Hoeffel put on a sterile gown, sterile rubber gloves, mask, cap, and the whole ceremonial costume. He prepared to do his work, stamping out disease among the sick and injured, when a fist started at the floor. The little guy had slipped into the operating area once more, and soon the fist on the floor quickly flew in a wide arc, ending up on Hoeffel's jaw.

Hoeffel tumbled head over heels across the room, ending up in a corner. I don't think he was knocked out, but he was certainly dazed. The nurses called the police, who made a tumult of their own arriving to do battle. But the little fellow was gone, never to be seen again.

Fifty years later, I had occasion to preside over a meeting of the Right Angle Club, where

Hoeffel's son, the former congressman and current deputy member of the Pennsylvania Governor's cabinet, was the featured speaker. He looked remarkably like his father. I had to wonder if his father's lesson in diplomacy had made any notable effect on his progeny.

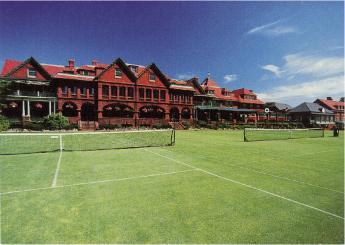

Lawn Tennis at the Cricket Club

|

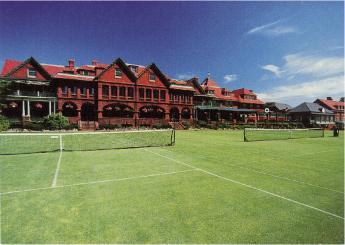

| Merion Cricket Club |

Lawn tennis isn't terribly ancient, having originated in England around 1880 as a variation of badminton which was brought back from India during the days of the British Empire. As the name suggests, it was originally played exclusively on grass courts, which proved hard to maintain. It was supplanted for a while by clay courts, and more recently by hard and artificial surfaces. Lawn tennis on lawns has largely become a game for the rich because of the cost and difficulty of maintaining a playable surface in hot weather.

If you wander into the Merion Cricket Club you'll find lawn tennis in the grand style, viewed from luncheon tables under a roofed porch. The long relatively narrow porch is right up against the grass courts, but it's also sort of a Peacock alley where well-groomed young ladies show their stuff, and everybody at the tables wishes to seem to know everyone else. There are times when the athletic entertainment becomes cricket out there on the field beyond the porch, but a larger proportion of the lunchers turn their backs on the field during that season than when exciting tennis championships are reaching the finals.

|

| "Lawn" Tennis |

In addition to being more expensive to maintain the courts, tennis on the grass is a different game from tennis on a hard surface, like clay or asphalt. The ball tends to skid when it hits the grass, so it is more effective to volley it before it hits or before it takes much of a bounce. The bounce tends to be more nearly straight up, while on harder surfaces the ball bounces at a low angle. Either way, the consequence is a tendency for a faster game on grass. The players run harder to get the ball at the bounce, and the advantage goes to those who serve hard and return the ball hard -- and fast.

|

| Cary Grant and Kathryn Hepburn |

The rather special nature of the game adds to the up-scale atmosphere. And makes it just as attractive for the Kitty Foyles at the tables, as for the Kathryn Hepburns, both of whom have their own attractions for the Cary Grants. The parking lot is also a good place to form an opinion about the latest in high-priced autos.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1494.htm

Rebel Hill

The Schuylkill River, hence Schuylkill Expressway and also Amtrak, all take a big bend westward about ten miles from Philadelphia. They are making a detour around a big hill or minor mountain, tending to position the sun in the eyes of many commuters at certain hours of the day. Real estate developers are apparently responsible for naming the place Rebel Hill, and it's getting pretty crowded with houses. The Rebel they had in mind was George Washington.

|

| Rebel Hill |

The father of our country was in retreat from the battle of Germantown, having crossed the river at Matson's Ford, then following Matsonford Road over and beyond the big hill, and pausing for water at the spring in the gulch formed by Gulch Creek, now more decorously called Gulph Creek. The creek tumbles down the side of a long ridge forming the south side of the Great Valley; the gulch or gulf is really a crevasse in that ridge, which in a sense makes Rebel Hill just a split-off extension of that ridge. Consequently, the gulch makes a water-level route from the Schuylkill to Valley Forge, which anyone would take to get there in a hurry. Valley Forge is a misleading term; it's a hill in the middle of the Great Valley, as the center of an angel food cake tin, and was thus defensible in all directions. The cleft in the southern ridge is where you would normally travel to get to the base of the bastion of Valley Forge.

|

| Old Gulph Road |

So, everyone still takes that route, following Montgomery Avenue after it turns into South Gulph Road, but before it turns into North Gulph Road. The road up along the southern ridge is called Old Gulph Road, while the newer extension from the river is called New Gulph Road. All of these winding roads are compressed within the narrow defile beside Gulph Creek, reachable by splashing through the fords in the creek, although that is discouraged after ice forms in the winter. And, yes, a new road has come in at a restored old farmhouse, called New Gulph Road. The restoration has created a fancy restaurant, which somehow forgets that at the time we are talking about, it was the headquarters of (Major) Aaron Burr. The giant highway cloverleaf ahead on South Gulph Road tends to obscure the fact that it was the direct road to Valley Forge, now further obscured by lots of shopping center. If you persist and keep a lookout for the street signs, you will eventually get to the Memorial Arch, log cabins and National Park Service facilities of Valley Forge.

|

| Valley Forge |

Back in the gulch, however, is the spring where Washington's troops refreshed their canteens. Just beyond it is a great big rock, much mentioned in memoirs of the episode. Around 1950, the highway engineers decided to blast this rock out of the way of widening a road that badly needs widening. The Daughters of the American Revolution saved the day. Creating a giant fuss, the DAR succeeded in limiting the engineers to chiseling the bottom of the rock away. A gentleman in his eighties recently remarked he had driven past that rock thousands of times, and always wondered what it was there for. Now he knows.

Main Line Oligarchy

|

| John Gunther |

"In the Philadelphia suburbs, set in an autumnal landscape so ripe and misty that it might have been painted by Constable....lives an oligarchy more compact, more tightly and more complacently entrenched than any in the United States, with the possible exception of that along the North Shore of Long Island....The Main Line lives on the Main Line all year around...It is one of the few places in the country where it doesn't matter on what side of the tracks you are. These are very superior tracks.....What does the Main Line believe in most? Privilege."

John Gunther -- Inside U.S.A.

Governor Keith's House

Route 611 begins at Philadelphia's City Hall and goes due north, headed for the Delaware Water Gap. In 1717 Lieutenant Governor Sir William Keith had decided he needed a summer residence to compliment his in-town establishment on Second Street, and acquired the 1200 acres of land of Samuel Carpenter on Easton Road, now Route 611. Sam had been entrusted with 2000 pounds against a possible French invasion, which Keith transferred to himself by taking Carpenter's land in lieu of it. The ethics of everybody in this transaction are now a little murky. The selected farm area was cool and tranquil, with creeks and level land, so a suitable three-story mansion was built of local stone, with outbuildings. A large mushroom-shaped rock was carved, polished and set on a pedestal beside the house. Tradition has it that Governor Keith asked servants and slaves to lift the stone as a test of physical strength. Keith had several negro slaves, eight or ten indentured servants, and others who were simply hired help for a rather large farm. Criticism was heard for the elaborate luxury of a mansion fifteen miles from town which it took five or six hours to reach.

Governor Keith was an interesting person. He inherited a Scottish baronetcy from his father and is the only Governor of Pennsylvania with a claim to noble blood. His finances were meager, however, and his life was a succession of efforts to advance his own wealth and position, which he regularly consumed with high living. He involved himself in coups and rebellions in Scotland, probably out of expectation of reward from the exiled King James. Efforts at court were finally rewarded by Queen Anne making him Surveyor-General of English land from Pennsylvania to Jamaica, but only after his nearly being hanged for treason for suspected efforts on behalf of the exiled former King James. Keith lost this essentially tax-collector position which he had performed creditably when the Hanoverian King George I took over the throne. After William Penn encountered difficulties which returned him to England, he and the Penn family were in need of an administrator in America, and Keith was at pains to ingratiate himself with Hannah Penn after William suffered several strokes from which he was to die in 1718. Most who met him felt that Keith was charming, although some regarded him as a charming rogue; he succeeded in ingratiating himself to the Penns and was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania in 1716, incurring substantial debts to transfer his family to America in style. After taking office, he wasted no time starting schemes and devices to enrich himself, while at the same time pursuing a populist political style which involved him in more or less constant controversy. There are many echoes in his career of that enduring subsequent conflict in America between creditors and debtors; as probably the most indebted man in Pennsylvania, his populism was highly troubling to conservative Quaker farmers. He pushed hard for paper currency, always popular among debtors, and probably sought to soften the feelings of the Quakers by pushing hard for the replacement of legally binding oaths with secular "affirmations". By doing so, however, Keith infuriated the vestry of Christ Church, representing widely held Anglican support for requiring oaths. Keith's pandering to differing viewpoints succeeded in infuriating James Logan, the secretary of the Penn proprietorship, into setting sail for England to seek Keith's removal from office. Logan only returned with a letter of admonishment from Hannah Penn, and controversy continued to simmer. Reduced to its essentials, a case can be made that Keith behaved like an unrestrained modern machine politician exploiting every opportunity he could find.

However, certain things can be said in Keith's defense. There is no doubt the Quaker farmers were hypersensitive about the display of wealth which a Scottish baronet would find quite appropriate for a man in his station. His mansion, for example, would barely qualify today as a five-bedroom house in the suburbs, and it is a little quaint to recall that generations of Penrose's and Strawbridge's subsequently lived on the property quite proudly, or even defiantly in view of their ample means. Paper money is indeed always the favorite of debtors who seek to dishonor their debts, but the colonies in Keith's times were suffering from a severe lack of space which can now be explained as the consequence of colonial terms of trade but which at that time was a severe economic hardship. His efforts to stop the practice of executing debtors may well have been made with his own indebtedness in the back of his mind, but still, it seems like a step in the right direction. Even the inventory of his property probably exaggerates the ostentation of his lifestyle. True, he had 144 chairs in the house, but the shortage of currency at that time had converted chairs into a form of exchangeable value, employed by almost every shopkeeper. Land was similarly used as a form of currency, although here most people would raise their eyebrows at a governor accumulating in eight years a list of property including not only this country estate and the downtown house in Society Hill, but a dozen rather large estates in other colonies, and a particularly troublesome investment in a copper mine on the west side of the Susquehanna. To some degree, Keith was a good Governor but was forced into a number of conflicts between the wishes of the settlers and the best interest of the Penn proprietors. Three thousand miles from the Court of St. James, he would scarcely be expected to display universal agility in shifting allegiance between the Stuart Kings, Queen Anne and the Hanoverian King George I, not to mention the Penn family and the settlers on their land. Keith did maintain reasonable stability in the colony while seeming to undermine the best interests of the Penn family. He was said to have made shrewd business decisions for the whole region converting surplus grain into malt at a time of money shortages in the colony, even though it particularly profited his own acreage. In some ways, his reputation remains chiefly tarnished by his treatment of Benjamin Franklin. Encouraging Franklin to go to England to buy some printing equipment, Keith promised letters of credit for what was presumably intended as a joint venture. The letters were never forthcoming, Franklin was stranded for months in England without means to return home. Franklin got his revenge years later in his autobiography. This was not the only example of Franklin nursing a grudge for decades. Poor Keith returned to England to defend himself against dismissal by the Penns because of all the turmoil and factionalism, but essentially never got another job and died in debtors prison. During that time he published extensively about current affairs and economics, but the value of that writing is now difficult to judge.

|

| Horsham Friends Meeting |

After Keith returned to England in 1726, presumably to defend his interests and possibly to evade his creditors, the mansion and estate on County Line Road was sold to Keith's son in law, Dr. Thomas Graeme who was a physician at the founding of the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1751 and evidently had become quite prosperous. Graeme paneled the interior of the mansion in high Georgian style, revised the floor plan, generally making the place elegant. Records of how the region between the counties became named Graeme Park, but presumably Graeme would now put up no objection to it. A second house on the property was home to several generations of Penrose's and Strawbridge's; the Strawbridge family donated the estate as a park. Governor Keith having left his wife forever to her distress alone, fathered two illegitimate children in England, making his prevailing emotions subject to uncertainty.

Around the corner, so to speak, on Route 611 the Horsham Friends Meeting is built of the same sort of stonework, with dates which suggest the meeting itself was present well before Keith appeared on the scene, and the string of similar but tavern-like buildings along 611 suggest the highway to Easton was a busy one even at an early time. Increasing traffic and construction carry an ominous prediction that growth of the area will eventually swallow both Graeme Park and Horsham Meeting in a sea of subdivisions and industrial parks. Placing a turnpike entrance nearby almost certainly hastened that fate.

Mennonites: The Pennsylvania Swiss

|

| On the Wall of the Mennonite Heritage Center |

Anabaptism, originally attributed to Ulrich Zwingli around 1525, centers around believing a baby is too young to understand baptism, so adults need to be re-baptized. The idea arose independently in Switzerland and Holland, and probably thousands of believers were unmercifully martyred for holding the belief. Because the worst persecutions took place during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-50), they are often attributed to the Roman Catholic Inquisition, but Magisterial Protestants, believing in the separation of church and state, were often also responsible. Many seemingly unrelated issues were introduced locally, and this period of unrest is known as the French and Indian War in America; its major battle took place in Louisburg, Nova Scotia, although George Washington's skirmish around Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) has acquired local fame as a major American manifestation.

The Swiss adherents moved to the Rhineland Palatinate, and from there were among the first to accept William Penn's offer of religious freedom. They were the settlers of Germantown, but have mainly moved a few miles west to southern Montgomery County, where the confusion about Pennsylvania Dutchmen is further confounded by the fact that they were Swiss. Menno the Dutchman gave his name to the order, but they themselves regard their true ethnic background as Swiss from the Zurich region. That, by the way, is not to be confused with Calvinism, which also comes from Switzerland, but by way of Geneva, not Zurich. The pacifism of the Mennonites made them mutually attractive with the English Quakers, who had made an appearance fifty or so years later in the region around Manchester, England; each group seems to have adopted some of the features of the other.

|

| Franconia Mennonite Meetinghouse |

Determined use of the German language has always held the Mennonites apart, however. From the start, it was really necessary to be somewhat bilingual in Montgomery County, using English for business conversation, and German at home and in the church. The idea of using a foreign language is based on the hope it would thus maintain a sense of distinctiveness or even remoteness from non-believers, without adopting the least hostility to them. It almost inevitably follows that the group has used its own schools, attached to their meeting houses. This sense of remoteness has persisted for almost four hundred years, surrounded by entirely different cultures. Starting only around 1960, this attitude has gradually softened, however, and it is widely assumed that in another few decades Mennonites will come to resemble the people in their environment a great deal more than they do at present. If you want to know where to find them, Harleysville is a good place to start. As the tinge of Pennsylvania Dutch accent gradually fades, and fewer of them wear the old costumes, a curious remaining hallmark of their presence can be noticed: an avoidance of foundation planting around their houses. The Mennonites themselves seem to be entirely oblivious to this unintended distinctiveness, which is however quite striking to non-Mennonite passers-by. Those who work in the fields all day have little interest in digging around their houses for decoration; those who have moved away from farming have seemingly adopted the bush-less style as a natural way of arranging things. There's no particular reason to change it, and so, there's no particular reason to notice it.

History of the Mennonites

Heavenly House

|

| Father Divine House |

While prosperous people, on deciding to enter a retirement community, are often heard to say they are tired of managing a big house, it can also be noticed that people who get the foreign travel bug usually drift around to see the palaces, castles, and estates of kings and emperors. The king's bathroom plumbing is a stop on most tours. Places like Buckingham Palace, the Vatican, the Temples of Karnak, Fortresses of Mogul Conquerors of India, or similar places in Cambodia, are all vast looming piles of stone dedicated to the memory of departed leaders who Had it All. That's probably all you need know, to understand that Americans who have it all tend to build huge show places, too. A great many do discover the castles to become just too much bother. Safe protection and privacy are somewhat separate issues, reasons given for putting up with a big place past the time the thrill has worn off. Perhaps such jaded feelings appear at the end of the wealth cycle. Nevertheless with enough affluence, if you had unlimited money and inclination, where around Philadelphia would you put a dream palace, one built for a modern Maharajah? Answer: close to Conshohocken.

|

| The Philadelphia Country Club |