Related Topics

Philadelphia Medicine

The first hospital, the first medical school, the first medical society, and abundant Civil War casualties, all combined to establish the most important medical center in the country. It's still the second largest industry in the city.

Philadelphia Physicians

Philadelphia dominated the medical profession so long that it's hard to distinguish between local traditions and national ones. The distinctive feature is that in Philadelphia you must be a real doctor before you become a mere specialist.

Medical Economics

Some Philadelphia physicians are contributors to current national debates on the financing of medical care.

Insurance in Philadelphia

Early Philadelphia took a lead in insurance innovation. Some ideas, like life insurance, flourished. Others have faded.

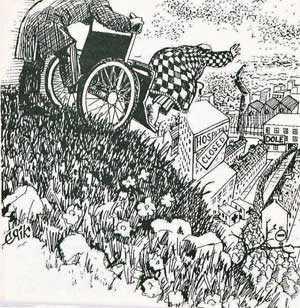

Clinton Plan Summary: Hospital Effects

|

| Hospital closed |

ERISA opened the eyes of employers. From roughly 1940 to roughly 1975, employers saw health benefits for employees as a tax loophole. Health insurance costs would be roughly 30% less if the employer paid for them than if the employee bought the insurance himself. Gradually, the realization dawned that employers were taking all the risks since their premiums went up if their employee claims cost went up. In effect, insurance companies were only providing administrative services but charging as though they were taking a risk. So, ERISA permitted employers to become self-insured for the group costs, but employ insurers to do the paperwork for a nominal charge. Although insurers had to agree to the arrangement, it was somehow important enough to maintain the brand name that they offered something valuable in return. Insurance companies, especially Blue Cross, had discount arrangements with hospitals. No matter what charge the hospitals made for a service, the actual payment would be based on internal audits of actual costs. For a long time, the effective discount was about 30%, it grew to 60%, and now it is as much as 90%. An electrocardiogram with interpretation, for which the market price in doctors offices is around $40. is charged $365 in one large teaching hospital in Philadelphia. If you enjoyed the discount, your cost was close to $40. When business leaders considered a switch from fee-for-service payment to HMO arrangements, it was vital that this discount is preserved. Stated another way, they were adamant that no one was going to impose these fictitious surcharges on them.

Becoming self-insured under ERISA taught them a second important thing. They saw to it that the claims came to them, or at least that the aggregated statistics they wanted were provided to them or their auditors. From this data, it seemed to these auditors that employers were somehow being overcharged anyway. They had neither the skill nor the access to data to know how it was done, but their conviction grew strong that they were not getting their money's worth. Many business executives were trustees of hospitals and were convinced the hospitals were not making excessive profits or were even actually running at a loss. If business was overcharged, and the hospital lost money, some other group of patients was being undercharged. Fairly or unfairly, the business community developed the firm conviction that what was happening was Cost Shifting. Never mind that incorporate conglomerates it is entirely legitimate for one subsidiary to subsidize another, or even at the retail level, for-profit margins on one product to subsidize losses in another. Or perhaps especially because this behavior is so evident to them, they found it necessary to be constantly on guard.

The HMO mechanism imposes expensive control systems on a dispersed medical enterprise which is really quite cost-effective, and neither needs do not welcome control. It has some obvious inefficiencies, but they are usually less costly than their seemingly more efficient substitutes. It would seem bizarre for business executives to spend their time managing employee medical choices when they are being paid to manage their own business. But the HMO structure offers one opportunity too tempting to ignore. If the employer substantially controls his employee health delivery, he is put in a credible position to threaten to move the whole group to a different hospital. That is the decision traditionally left entirely in the hands of physicians, thus clarifying the main reason employers have seen physicians are ultimately their enemies. Obviously, local physicians are in the best position to judge the relative merits of local facilities, and therefore obviously physicians will resist anyone who suggests making those decisions for any other reason than the ones they can see. If you don't see this analysis as obscene insolence, you will probably agree it is extremely shrewd. Hospitals are somehow cost-shifting us into bankruptcy, we don't know and don't care, how. The way to get them to lower their prices for our employees is to have a credible threat of moving the whole bunch to some other hospital and, yes, bankrupting this one as an example for others.

So now perhaps it is possible to see the position of hospital administration in the post-Clinton years. Hospitals have long had forty to sixty percent of their patients represented by federal auditors empowered to examine every scrap of their internal accounts. Now, inside a sort of medical Alamo, they have forty to sixty percent more patients represented by hard-faced HMOs who have the power to shift half their business to a competitor on a few weeks notice. Inside the Alamo, there may have been other choices, there may even have been better ones. But the defense against this blood-thirsty onslaught which was agreed upon was, reduce the number of hospitals, either by merger or destruction.

Several books have been written about the expensive chaos created by merging hospitals; the loss of neighborhood facilities is much mourned. It must be left to others to calculate the aggregate cost of this scorched earth defense. But it has been considerable and is part of the cost of the Clinton Plan, or if you please part of the skyrocketing cost of medical care which calls for drastic reform. It is a heavy cost in any event, and like so many features of modern medical care is not assigned to the business leadership which provoked it.

It is in this way we see the current paradox of massive building and expansion plans in hospitals across the country, at the same time that the number of hospitals is drastically reduced. There were 120 hospitals in the Delaware Valley in 1970, and now the number is around forty. Some of this can be blamed on the malpractice liability mess since lawsuits heavily concentrate around obstetrics. Obstetrical facilities at the southeastern corner of the state can easily shift across state lines. Other closures allude to the savings in administrative costs, which would make you giggle if it did not make you cry.

Let's end this summary of hospital uproar with a brief mention of its simple solution. There is no need to mention increased waiting periods in crowded accident wards, or extravagant streamlining of patient throughput in order to reduce bed capacity or the disappearance of reserve bed capacity in the event of a major disaster.

All of these problems would go away if we reversed the Maricopa decision and relaxed antitrust strictures against the ownership of HMOs by local physicians. Local physician reviewers may well squeeze hospital costs, but they will never move themselves to another hospital. Managed care by Health Maintenance Organizations may or may not be a good system, but having such organizations controlled by payors without allowing physician-owned competitors as a restraining benchmark has been thoroughly tried, and is a disaster.

Originally published: Thursday, August 02, 2007; most-recently modified: Sunday, July 21, 2019